Review: ‘The Shark Is Broken’ Takes a Very Funny Bite Out of ‘Jaws’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

First, all Jaws fans be fair warned: There is no shark in Ian Shaw and Joseph Nixon’s excellent Broadway play, The Shark Is Broken (Golden Theatre, booking through Nov. 19). The only semblance of the iconic 1975 serial killer and wanton dismemberer of unfortunate swimmers are a few seconds of familiar forbidding music and the sight of that fin scything through Nina Dunn’s watery video design that forms the backdrop to the stage. Then we see that fin blowing up and sinking.

The image of the imploding fin crystallizes the focus of this 90-minute, intermission-less play: the tensions and clash of personalities between the three leads of the movie—Robert Shaw (played by his son Ian Shaw), Richard Dreyfuss (Alex Brightman), and Roy Scheider (Colin Donnell)—as filming is constantly delayed by the malfunctioning model sharks, nicknamed “Bruce” after director Steven Spielberg’s lawyer Bruce Ramer, that the production utilized. Only one “Bruce” reportedly remains intact, and it is housed at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles.

How the Bloody Feuds of ‘Jaws’ Became ‘The Shark Is Broken’ on Broadway

The play, directed with a guileful brevity by Guy Masterson, is, in one sense, intensely personal because of Shaw’s writing and performance. He looks so like his father and the play both shows Shaw Sr. as a very funny, pugnacious, grizzled-way-too-young character actor and also a bellicose, alcoholic bully who guzzles booze, holds forth, seethes, and—in quieter moments—reveals the private pains hidden behind his sulfurous exterior.

Fans of the film will immediately recognize the men and the setting, thanks to Duncan Henderson’s lightly ingenious set and on-point garb. The three actors, dressed in the distinctive clothes the actors they are playing used for their characters, are marooned on the Orca, the boat the characters used as the vessel for the final confrontation with the shark.

Henderson has even created a large, shark bite-sized-looking hole in a portion of the front of the boat, so we can see the men better. They exit and enter the stage by clambering gingerly down the back of the craft. The trio are trapped, and the comedy and drama of the play comes from their enforced confinement. They’re not companionably three-men-in-a-boat, and neither are they waiting for Godot, they’re waiting for a goddamned model shark.

(l to r) Colin Donnell, Alex Brightman, and Ian Shaw in 'The Shark Is Broken.'

The hassle-strewn crucible of filming Jaws has allowed Ian Shaw to put his father on trial—an ultimately loving one, but an insightful, tough one nonetheless. Shaw told The Daily Beast last week it was easy to take his father on and shrug him off every night, but it’s an impressive performance—playful, respectful, yet also not afraid of dwelling in, and implicitly criticizing Shaw’s darker side. The play also interrogates acting, celebrity, and film-making from the acute vantage point that, at the time we see these men kvetching and combusting, they do not know how successful and influential Jaws will become.

Shaw Sr. says he thinks the film “is destined for the dustbin of history—like the other big beasts of this decade; The Towering Inferno, The Exorcist, Love Story, Airport. Do you think anyone's going to remember any of those?” There are many lines in the play like this, deployed for the sighs and groans of a modern audience who knows the outcomes all too well.

The play is rooted in fact: Shaw and Nixon have excavated material from Jaws co-screenwriter Carl Gottlieb’s book, The Jaws Log, as well as a number of documentaries, interviews with Spielberg, Dreyfuss, and Scheider, and Robert Shaw’s drinking diaries.

Shaw, Brightman, and Donnell astutely nail the three contrasting actors playing salty seadog Quint, puppyishly excitable scientist Matt Hooper, and cool town cop Chief Brody. The spine of the play is Shaw trying to master Quint’s speech, delivered in the dead of night to the Orca’s swaying light, recalling some of the USS Indianapolis’ crewmen being eaten alive by sharks when the boat sank in 1945—having “just delivered the bomb, the Hiroshima Bomb”—after being torpedoed by the Japanese.

Ian Shaw as his father Robert Shaw in 'The Shark Is Broken.'

We see him have a series of false starts with the speech—he feels it is terribly written, and so he will rewrite it; a second attempt is derailed because he is so pickled in booze; and the third attempt—the speech delivered in full—makes for a perfect finale. To get there, we see how oddly the men’s off-camera characters matched their on-screen ones.

Shaw and Dreyfuss’ dynamic is full of conflict just as Quint and Hooper’s was: Shaw dismissing the younger actor’s chasing of fame and celebrity, while reveling in his hard-man, hard-drinking old-school behavior that was in such contrast to Dreyfuss’ neuroses, seasickness, and New York Jewish snark. Just as in Beetlejuice, Brightman impressively puts himself through the physical wringer as his Dreyfuss tries desperately to counter Shaw’s intimidation and assert his own self.

Scheider, just as Brody was, is the come-on-guys peacemaker, who reads the paper (Nixon and Vietnam loom large, providing a further symbolic framework for the play), and gets stressed about the state of the traffic in Martha’s Vineyard. “Roy, stop! You’re talking about roads again!” implores Shaw jocularly.

Donnell has perhaps the toughest job, bringing life to Scheider-the-sensible-one; a block of human granite, his proudly dull preoccupations usefully douse all the out-of-control passions of his two co-stars, until—in a solo scene—Donnell, clad only in a black Speedo, reveals another side of himself. Together, all three make for bristlingly fun company.

None of the men disagree about wanting the shoot to end as soon as possible. “How many of those things they got, anyway? Three? Four? We’ve been on this boat, what, five days? None of them fucking work. This whole thing is a disaster,” Dreyfuss says. “Why are the goddamn things so unreliable? They can put a man on the moon but they can't make a mechanical fish that floats?”

Hungering wistfully for deviled kidneys on toast, Shaw torments an already almost-broken Dreyfuss, who as much as he is a victim of Shaw’s anger, also looks up to him, hopes he can help his career, and then finally tries to help him as he sees the destructive swathe drinking is cutting through Shaw’s life (and holding up the film). Off-stage, at moments, we hear Spielberg’s increasingly weary voice.

As their time on the Orca drags on, Shaw gives Dreyfuss withering lectures on Damon Runyon and Neptune and Poseidon (“Christ, what did they teach you at school? They’re the same bloody god!”). “Four weeks is a long time to be stuck on a slow boat to China with Brigitte Bardot and Rachel Welch. With you two it’s a fucking eternity!” Shaw shouts. As scenes shift, we watch cloudy and sunny days bubble up behind the boat, dark nights, and violent storms—adding to the sense of terminal stasis.

(l to r) Colin Donnell, Alex Brightman, and Ian Shaw in 'The Shark Is Broken.'

Shaw tells Dreyfuss to stop whining, yet he himself is obsessed with the money he could make, and artistically dismissive of what they are making. “Do you imagine it's going to be a second Citizen Kane? It’s bread and circuses, chums. I pray this is as simple-minded as Hollywood films ever get.”

Dreyfuss fires back: “I’d be interested to learn how you square your ‘left-wing principles’ with the large sums of money you make. I mean, presumably you donate your entire wages to the workers.”

In some ways, as well as its deeper strains, The Shark Is Broken is also a play about bored, restless men being assholes around each other: goading, competing, joke-telling, brooding, and being merrily puerile. As Dreyfuss winds the older actor up, Shaw menacingly takes out a knife, followed—a beat just long enough for fear to bloom on the men’s faces—by an apple. Dreyfuss is too fat, Shaw says, leading to the younger actor getting down to do press-ups (“We call them push-ups over here”). The men mull how sports like golf can be seen as a fertility rite. Dreyfuss says, “I don’t think it works with baseball. There you have a guy trying to get his sperm past another guy, who is trying to hit his sperm out of the park.”

Shaw, who says he wishes he had been a professional rugby player (“When you score a try, they can't take it away from you”), claims actors need to pay their dues. “Fame is the by-product. It is the shit of art!”

Dreyfuss is having none of that. “I’m an artist, OK, I want to make art. If I happen to make a million bucks, get blown a hell of a lot, maybe make the cover of Time magazine along the way, then where’s the harm? You think Shakespeare didn’t get blown? Sure he did!”

Roy Scheider as Chief Brody, in the movie, 'Jaws.'

Ian Shaw has co-written a clever, generous play with three terrific performances. We cheer when Dreyfuss aces Shaw in a baffling game called Shove Ha'penny, and when he holds forth, impersonating Shaw’s portentous showbiz bragging and unasked-for-life lessons: “When I was on the London stage playing Macbeth back in 1906, Sir Robertson Fuckwad said to me, he said to me, ‘Shaw, you are the biggest douchebag I have ever had the misfortune to have met.’”

Shaw Jr. contrasts the shallow and deep as the men josh, argue, bond, and fight some more. He can craft a moving speech harking back to his father’s childhood in the remote Orkneys, then end it drily with Shaw Sr. recalling: “The other children made my life hell. I'm sure it would have been worse if I'd been able to understand a word they were saying.”

Robert Shaw’s father ended his own life at 52. Shaw himself was 47 when he filmed Jaws, wondering if he would live past his father’s death age (he would not; he died in 1978, aged 51). Shaw tells the men he used to dream his father “was walking with me in a beautiful place and I was holding his hand and I’d say: ‘Everything’ll be alright, Dad.’”

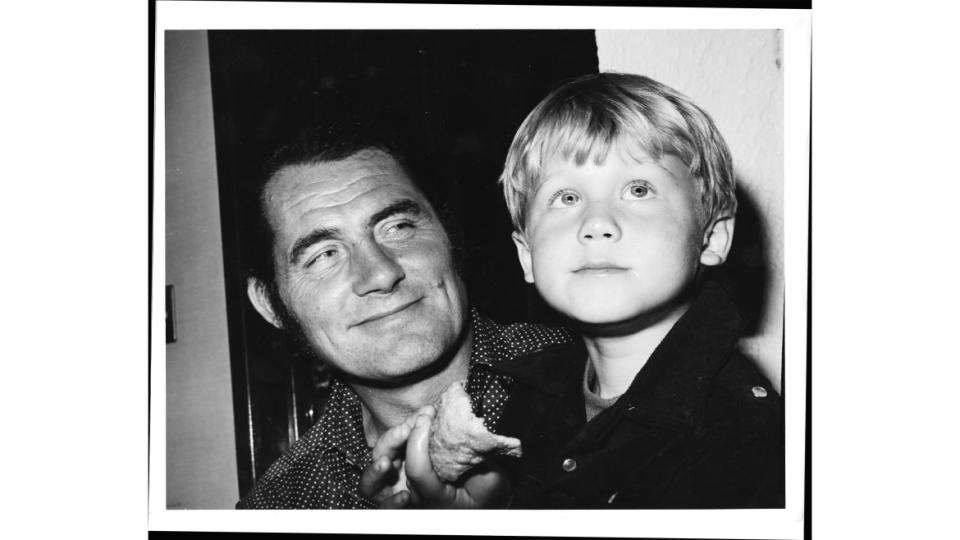

Robert Shaw, left, and his son, Ian Shaw

Shaw, perhaps realizing his targeting of Dreyfuss has gone too far offers consolation after the latter has a panic attack, sits next to him and recites Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29—no flowery or booming Olivier-isms, just a simply recited piece of verse intended as a gentle arm around the shoulder.

Then Scheider is freed from being Mr. Responsible: clad in the Speedo he holds a baseball over a crackling radio, a producer telling him to get ready for his next shot. He is just as frustrated as the other two but knows better how to hide and marshal it.

The last moments of the play are replete with Easter eggs for fans of the movie, and not-overdone winks to a future we know, and they do not. Dreyfuss mentions a film about sympathetic aliens Spielberg is lining him up for (we know it to be Close Encounters of the Third Kind).

“UFOs! Aliens! Jesus! Whatever next? Dinosaurs? Can this business get any more puerile?” Shaw bellows. A sequel to Jaws? “What on earth could happen with Brody in a sequel? Another shark comes to town? That’s crazy!” Scheider exclaims. We know that in three years time, he will take the lead in Jaws 2. And oh Roy, you want to say, just wait for Jaws 3.

“Mark my words, boys, one day there will only be sequels. Sequels and remakes, and sequels to remakes and remakes of sequels,” Shaw says ruefully, and prophetically.

Finally, the men wonder what Jaws is about anyway, just as the deeper meaning of the film has been chewed over in all the years since. Scheider thinks “it’s about responsibility... when the government puts profit before people’s lives, if you can't get rid of the bastards, you’ve gotta take care of the mess yourself—even if it terrifies you, for the good of the community.”

Asked for his thoughts, Shaw-as-Shaw pauses a perfect moment before delivering, in bug-eyed exasperation, a line that deservedly brings the house down. “It’s about a shark!”

Director Steven Spielberg in the mouth of 'Bruce' while filming 'Jaws.'

“Do you really think people are going to be talking about this in fifty years?” he adds a moment later, showing his crystal ball is just as faulty as it is functioning. The final shot soon-to-be-completed, the men know giddily that freedom will soon be theirs. But what they don’t know is that Jaws will go on to become the cultural totem we know it as today—and it is in the humorous and profound gap of past and present, known and unknown, and ignorance and wisdom that The Shark Is Broken wittily excels not just as a clever time capsule, but as an examination of male bonding and competitiveness, ego, frailty, fame, and film-making.

Which is to say: You don’t miss the shark for one second.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.