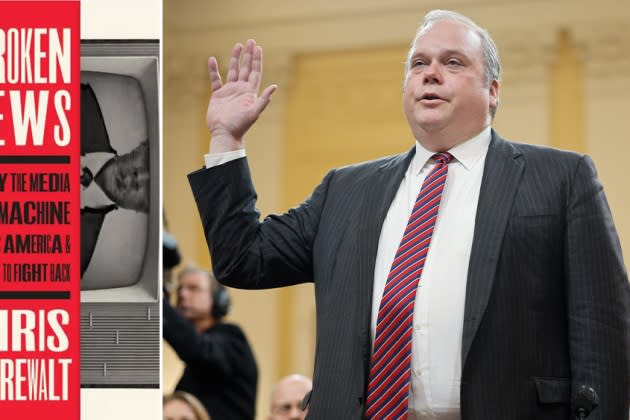

‘Broken News’ Book Review: Chris Stirewalt Chides Fox News For “Black-Helicopter Level Paranoia” But Targets Plenty Of Other News Outlets For Stoking Rage For Ratings

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Less than two weeks after the siege of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, Fox News dismissed its political editor, Chris Stirewalt, in what the network said was a restructuring and he said was a firing.

As many media reporters and commentators noted, Stirewalt had defended the network’s correct call of Arizona for Joe Biden on election night, the first sign that Donald Trump would lose the 2020 presidential race. What resulted was a backlash from Trump and his supporters, not just “insane rage” directed at the network, but also against Stirewalt himself. One Republican senator, Kevin Cramer, accused him of a “cover-up,” as if Stirewalt himself had been counting votes.

More from Deadline

Sean Hannity, Tucker Carlson And Lou Dobbs To Be Deposed In Dominion Lawsuit Against Fox News

Fox Nation To Release First In-House Movie Production 'The Shell Collector'

Stirewalt’s new book, Broken News: Why the Media Rage Machine Divides America and How to Fight Back, delves into his dismissal, but this is hardly a tell-all, or singularly focused expose of what’s happened to his former employer.

Rather, it makes the case that the news business, in its desire for viewer and reader engagement, has tilted too heavily toward giving the audience what it wants to hear, rather than what they need to know. He argues that, in the quest for attention in an ever-fractured environment, news outlets have prioritized stoking emotion — grievance, anxiety or anger — over their civic-minded duty of informing their audience.

“Every day, editors and producers go hunting for any story that will either flatter their outlet’s target audience or, more likely, show the fundamental inferiority or evil of the other side,” Stirewalt writes. “They don’t do this because they are bad people themselves or even necessarily aligned with the slant of the story. It’s just that this kind of contempt is profitable because it is easy to trigger. To get someone to look at a story in an impartial way takes a lot of work.”

Stirewalt shares an anecdote from earlier in his Fox News career, when he attended an Election Day 2010 meeting with high-level Fox News executives, and then Fox News head Roger Ailes wanted to know how many seats he thought Republicans would gain that evening. Stirewalt answered 64.

“Dick Morris says it could be one hundred. Why is yours so low?” Ailes shot back.

Stirewalt writes that he didn’t come out and say that he thought Morris’ predictions were a joke, designed to get the pundit attention on his Sean Hannity guest shots. Nor did Stirewalt back away from the analysis, either, which turned out to be nearly correct. (The GOP won 63 seats that year.)

“The story they were telling was good for ratings or the frequency of their appearances,” Stirewalt writes. “They wanted it to be true because they wanted Republicans to win, but keeping viewers keyed up about the epochal victory close at hand was an appealing incentive to exaggerate the GOP chances. It was good for them to raise expectations, but it wasn’t good for the party they were rooting for.”

There certainly have been many books that have mined that same themes, some from academics, others from politicians out to settle scores against “the media,” but Stirewalt pitches this book as a little different, from the view of an insider who’s seen quite a bit in his career.

He does offer up some criticisms of Fox News while acknowledging that he “has not always been on the side of the angels.” He calls out the network’s decision to program the Tucker Carlson January 6th documentary on its subscription Fox Nation streaming service.

“Fox is inciting black-helicopter level paranoia and hatred to get viewers of its free cable news channel to sign up for a sixty-five-dollar ‘Patriot’ package on its subscription streaming service,” he writes.

Stirewalt counters the idea that Fox News is a tool of the Republican party. Instead, he argues, it’s the other way around. Case in point, when Ted Cruz came on Tucker Carlson’s show earlier this year to apologize for referring to the siege on the Capitol as a “violent terrorist attack on the Capitol.”

“Even given Cruz’s superhuman capacity to endure humiliation in pursuit of power, it was hard to watch,” Stirewalt writes. “That doesn’t sound like ‘A Plan for Putting the GOP on TV News’ that Roger Ailes pitched to Richard Nixon in 1970 and then brought to life twenty-five years later. It sounds more like a party that has been captured by an enterprise that does not share its same goals.”

A Fox News spokesperson said in response to Stirewalt’s book, “Chris Stirewalt’s endless attempts at regaining relevance know no bounds.” Arnon Mishkin, who leads the Decision Desk that made the Arizona call, still works for the network and will be returning for the midterms, according to the network.

Stirewalt doesn’t confine his critique to the right, but all across the media spectrum. The book starts with the Washington Post newsroom and its “leaderboards that show which stories are clicking the best with readers in the digital world.”

His point: Even on the day when the fall of Kabul was a major international story, the “big mover” was a story headlined, “A conservative cardinal who criticized the vaccine caught covid. Days later, he was put on a ventilator.”

“Even on big news days, Post readers reliably plus-up stories that follow a couple of simple narratives: either wicked right-wingers getting their just desserts or the plights of innocents suffering because of right-wingers’ behavior,” he writes.

He writes that the New York Times and its 1619 Project, with a stated purpose to “destroy the idea of the American Creed,” was little different from what Fox News was doing in suggesting that the January 6th attack was a “false flag” operation. The Times, he noted, was “using a frontal assault on the idea of America’s founding as a new birth of freedom that it very plainly, if imperfectly, was in order to upsell super-users from subscriptions to thirty-five-dollar books.” Plenty of Times editors, as well as the Pulitzer organization, likely will differ on this point.

The book’s publisher is Center Street, which, ironically enough for a book about news bubbles specializes in conservative titles. Yet even though there are Trump-supporting authors like Newt Gingrich and Mike Lee among its lineup, Stirewalt, now politics editor at NewsNation, is no apologist for January 6. He testified before the January 6th Committee and is a contributing editor of The Dispatch.

What he does warn about is “apocalypticism,” or overdoing it when it comes to writing about issues like education, democracy or climate change, as well as the whole idea that reporters, with Trump-triggered notions that democracy itself is under threat, should abandon an attempt at objectivity.

“Americans need more common spaces in which they can have confidence not only that information will be accurate, but that points of view will be fairly represented,” he write. “We will always come up short in our inclusivity, impartiality, and capacity for holding bad actors to account, but if we throw away aspirational fairness in favor of activist, opinionated journalism we are not fighting entrenched power, but feeding it.”

His arguments are certainly not new in media commentary, but in book-length, they are typically from the academics or politicos hoping to settle some scores. Stirewalt’s is a bit different in that he’s got an inside view, having worked his way up from local newspapers in West Virginia to the Washington Examiner to Fox News. In other words, he knows the tricks of the trade.

He’s also got a passion for history, one of the strengths of the book. He traces other times of trouble for the news media, going back to the times of the founding fathers, when all news was partisan, to the rise of radio, when hosts regularly spewed propaganda. As if not to get too apocalyptic, he notes that the country’s media ecosystem faced similar times of upheaval before and still survived.

As much as Stirewalt shines a light on what is broken, his focus is largely on political coverage and less so on where the business still excels. Even the cable news networks, obsessed as they are about ratings, produced compelling coverage of the war in Ukraine and continue to station correspondents throughout the region despite the safety risks.

So often, when people complain about “the media,” painting it with one broad brush, they are focused on just one aspect of it, usually the 24-hour news networks. The more sober network evening news broadcasts, while certainly not as influential as they once were, still regularly get larger audiences than the highest-rated cable news shows.

Stirewalt has a good point about viewer fatigue over the non-stop stream of crises, and CNN’s new CEO Chris Licht has recognized this by limiting the use of breaking news banners. But in a number of cases the sirens of imminent peril aren’t coming from left-leaning journalists but by subjects of coverage, like conservative Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY) and J. Michael Luttig’s warnings about the state of democracy as they spoke at the January 6th Committee hearings.

Stirewalt offers a set of solutions, such as curbing the use of anonymous sources or treating politics as a sport. He makes the point that as the volume of news coverage increases, “the quality of that coverage seems to be constantly in decline.”

That may be so, but what’s unclear is whether there is a primetime cable audience to counter sensationalism, partisanship and celebrity fixation. Stirewalt’s employer NewsNation launched in 2020 by pitching itself as an unbiased news source, and the audiences have been a fraction of its well-established rivals. It’s since tried to move more to personalities, with Dan Abrams and Ashleigh Banfield hosting shows, and, coming this fall, Chris Cuomo.

Best of Deadline

Venice Golden Lion Winners : Photos Of The Festival’s Top Films Through The Years

'Meet Cute' Photo Gallery: Kaley Cuoco And Pete Davidson Star In Comedy About Falling In Love

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.