The Return of Pastis, and the Man Who Made New Yorkers' Dreams Come True

Pastis-the original Pastis-opened twenty years ago. It’s not as though we’re talking about ancient history.

And yet to get a sense of what the neighborhood felt like when the restaurant made its debut, you will want to start by scouting around for vintage photographs, as if you were rewinding to bygone, black-and-white street scenes captured by the likes of Berenice Abbott, Garry Winogrand, and Weegee. Abandoned cars, crumbling facades, prostitutes on the prowl. Go online and gawk at the grunge. Even at the tail end of the twentieth century, the Meatpacking District looked like what its name implies. It was a neighborhood on the physical and social margins of Manhattan. The packing houses with their swaying carcasses on hooks had begun moving out decades before, but their splatters of blood had been replaced by splashes of graffiti, and their caverns had been usurped by sex clubs.

Keith McNally took a walk one day and surveyed all this, and loved it. “It felt like the world’s end,” he recalls. “Raw. Natural. Alive. A healthy mix of meatpackers and transvestites.” In 1999, McNally was riding high on the success of Balthazar, the all-day SoHo brasserie that celebrities seemed to adopt as their canteen before they’d even gotten a peek at the red leather banquettes. The guy was in the zone, and he was wondering what to do next.

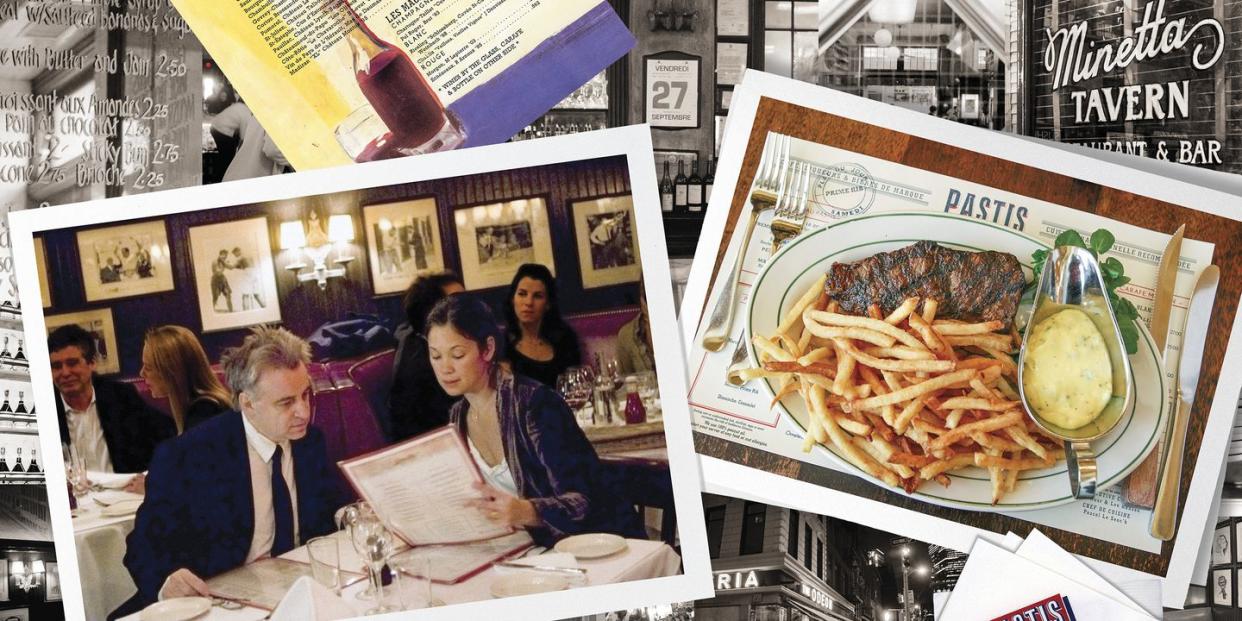

He’d been one of the two brothers behind the Odeon (he sold his shares to Lynn Wagenknecht after their divorce); he would go on to hatch Morandi and Minetta Tavern. Oh, and let’s not forget Pravda, and Cafe Luxembourg (which was also bought out by Wagenknecht following the split), and Nell’s (that one, too), all of which came to capture a moment of time in the social history of New York City, and all of which the London-born boulevardier had conjured with a private attention to detail that verged on mania and a public mien that masqueraded as ennui. (As his websites put it, “In 2010 he was mistakenly given the James Beard Award for Outstanding U. S. Restaurateur.” Interviewed by Gabe Ulla for Eater in late 2016, he said: “Underneath it all, without being coy, and like a lot of people, I feel fraudulent. I do. That’s not a put-on.”)

He had come to New York in 1975, busing tables and later shucking oysters after a brief interlude as an adolescent actor in England, and he had, in keeping with the New York tradition, transformed himself by instinct, charm, and industry into one of the city's defining social gatekeepers. People told Keith McNally he was successful, but he never seemed to believe it, or at least, in keeping with the British tradition, he did a deft job of pretending that he couldn’t care less.

There in a cobblestoned expanse that concealed Manhattan’s rarest commodity-cheap, abandoned real estate-this tousled avatar of insecurity decided to put a place where you could get steak frites late at night. It wouldn’t be French so much as French-ish. (It’s no accident that the twin-set of chefs he brought in, Lee Hanson and Riad Nasr, currently run a restaurant called Frenchette.) Back then, as now, he had a talent for summoning up an oasis of style and indulgence in precincts that might, to the untrained eye, appear barren. “A truism about McNally’s restaurants is that they are like stage sets, with a theatrical sense of lighting, of casting, of narrative, of scale and movement and mise-en-scène,” Benjamin Wallace once wrote in New York magazine. “Meticulously engineered to feel like found objects excavated from a golden past that never was, his places are augmented-reality versions of the bistro, the brasserie, the trattoria, the cafe, the tavern.”

And for this, his next trick, McNally liked an isosceles triangle of roadways in the Meatpacking District, a spot where Gansevoort Street shot toward the Hudson River and Little West Twelfth angled northward. “Stumbling across the desolate piazzalike intersection of Ninth Avenue and Little West Twelfth Street in 1999 is what prompted me with the idea of building a cafe there,” he says. “The cafe turned into a restaurant, but central to the idea of Pastis is a European cafe.”

To this day, he talks about Pastis offhandedly, with no detectable trace of sentimentality. He opened the restaurant in 1999 and closed it in 2014, because he had become, in essence, a victim of his own foresight. Pastis ushered in the big-money deluge that nearly obliterated it. As he says, “The original Pastis was forced to close because of a landlord driven by avarice.” Google Street View the location of the original Pastis now and you’ll find a Restoration Hardware.

But there are plenty of people who believe, looking back, that Pastis was more than a restaurant. “Balthazar and Pastis turned the Western world upside down,” says Stephen Starr, who has joined forces with Team McNally to raise Pastis from the tombs, a la Lazarus. Starr, the Philadelphia-based restaurateur who was first smitten with the McNally aesthetic as a music promoter in the 1980s, recalls walking up to Pastis in its gritty genesis and getting swept away by its hum and glow. “You saw that red awning and you went, Ahhhhhh.”

Pastis was more about mise-en-scène than mise-en-place: A lot of chefs in 2019 may want you (even instruct you) to gaze in wonder upon the delicate edible origami of their knifework, but Pastis in 1999 wasn’t about the chef. It was about you, and how you looked a tad more spiffy in McNally’s Provençal-sunset lighting, and how the flirtatious electrons filling the air put you in the mood to order another bottle of Chateauneuf-du-Pape and make out with your date on the street. Having to wait for a table could be taken as a sign of unexpected good fortune: The crowd barnacled around the long bar, ordering pastis-laced cocktails like Le Casa-Tête and Le Feu Rouge for $8.50 each and trafficking in eye contact and quips-the IRL connectivity that ruled the world before today’s social default mode of staring at your phone. “Once Mr. McNally declared his intention of opening a humble French restaurant in the meatpacking district, the rush was on, and it’s an act of mercy that he included a zinc bar, because that’s where most diners wait, ten deep, for a table to open up,” wrote William Grimes in The New York Times, describing the scene. “That might mean two or three hours. No one seems to mind.”

As Starr puts it now, “It was Meatpacking. It was dangerous. It was open till four in the morning. It felt like a revolution.”

Pastis-the new Pastis-will open this spring.

It is an understatement to say that a lot has changed in the intervening two decades.

Pastis will make its second debut at 52 Gansevoort Street, in the same Meatpacking District whose gentrification it helped instigate. The neighborhood has, for anyone who traversed it back in the early 1990s, become unrecognizable. Gone are the butchers and the grime. Gone, too, are the early agents of change that had preceded Pastis: Hogs & Heifers, the theatrically skeevy honky-tonk, as well as Florent, a casual Gallic way station where the free-spirited French immigrant Florent Morellet nourished the outcasts with onion soup and compassion. (As Calvin Klein once told Frank Bruni, when asked about Florent: “It was downtown. It was real downtown.”) In their place, you now find a scrubbed, pedestrian-friendly showcase for late-stage capitalism, a cuteness-overload bonanza of boutiques-Tory Burch, Madewell, Bumble and Bumble. (Florent’s former shell now encloses the Madewell.) There are flood tides of tourists who navigate the sidewalks in zigzagging, phone-gazing clumps. There are bros who want to party at high volume because some reality show told them to. A towering new iteration of the Whitney Museum of American Art occupies the corner of Gansevoort and Washington streets, and the High Line-the serpentine garden walk that has spruced up this western edge of Manhattan-ends (or begins, depending on which direction you’re going) its trail a few steps from the museum’s entrance.

The neighborhood is nice now.

In an email, I asked McNally what emotions came to mind when he thought of the Meatpacking District in its present form. (He also lives in London these days, in a house in Notting Hill as meticulously decor’d as one of his restaurants, but there was a medical reason, as opposed to a geographical one, for McNally’s request for an email exchange: After enduring a stroke recently, he feels more comfortable with digital conversation.)

He answered this way: “Rage at the unsightly hideousness of the Gansevoort hotel and Restoration Hardware and, apart from the beauty of the High Line and the new Whitney, the general disfigurement of a once-beautiful neighbourhood.” (McNally’s British spelling will be offered without alteration in this article, although I expect a skirmish with our copy desk about that.)

No one can pretend that the experience of going to Pastis in 2019 will feel quite like the experience of going to Pastis during its first bloom. The Meatpacking District is a mall. After McNally’s stroke, which reportedly spooked the first group of potential investors in the Pastis revival, his daughter Sophie brought in Starr, who happens to own his own bustling McNally-ish bistro in Philadelphia, called Parc. “It’s Keith McNally playing a classic song that no one’s ever going to get tired of,” Starr says. “It will look the same. The bar’s almost exactly the same. The food will be better.”

The context will be different, though. It can’t help but be. When Pastis came into being, New York City had not endured the deflation of the dot-com stock-market bubble in 2000 or the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center the year after. Odd as it is to imagine now, Pastis opened in a time before the culinary revolutions brought about by David Chang and April Bloomfield and the two Franks, Castronovo and Falcinelli: If McNally restaurants exuded the luxe swagger of the Rolling Stones, Chang’s Momofuku experiment countered with the spiky, democratic austerity of punk rock, making the celebrity-courting, red-leather-and-distressed-mirrors aura of Balthazar and Pastis feel a little bit clubby, insular, and conservative in comparison.

And then there’s the food. McNally has never been shy about his resistance to gastronomic innovation. During the two decades following the dawn of Pastis, the molecular-gastronomy movement flared up and fizzled out, only to be replaced by the next wave, the New Nordic movement associated with Rene Redzepi’s Noma in Copenhagen, with its emphasis on foraging and fermentation. “I’m still reading Escoffier’s 1903 Le Guide Culinaire,” McNally says (via email, yes, but you can still hear him sigh). “When I finish it I’ll probably move on to New Nordic cooking. Or molecular gastronomy. Until then, I can’t really talk about either.”

There is no valor in trend chasing, of course, and McNally’s commitment to warhorses like onion soup and frisee aux lardons and gougeres and duck a l’orange helps explain why his venues continue to make money: People like eating these, and they prefer to do so in a room whose amber lighting makes diners look twenty years younger.

But at the same time, spectacular upstarts around the country, like the Grey, JuneBaby, Nyum Bai, Dyafa, Atomix, Bad Saint, Cosme, El Jardin, Celeste, Han Oak, and Mission Chinese Food, have continued to dislodge the presumed centrality of the white male Eurocentric canon on the American food scene. Opening a French restaurant these days runs the risk of looking like an act of nostalgia, or even crusty fogyism, a perception that’s doubled when you’re opening a nostalgic reboot of a restaurant that was already an overt act of nostalgia in the first place. When he reviewed Pastis in early 2000 for The New York Times, giving it one out of four stars, Grimes made it clear that performative longing for a different time and place didn’t come cheap. “Visually, Pastis is perfect,” Grimes wrote. “Annoyingly so. Each crack, wrinkle and stain has been calibrated with a micrometer: rough-hewn planks on the floor, simple dark-leather banquettes, paper menus with period type and artistically flawed antique mirrors, ‘carelessly’ daubed with a list of the day’s dishes.”

Grimes ended his review with an omen. The original Pastis had been created with the hoi polloi in mind; ideally it would’ve served as Balthazar’s populist alter ego. “There aren’t many meatpackers, but there is the usual mix of youngish downtowners and nondescript professionals, dying to see what the fuss is about,” Grimes observed. “But things could change. The long black vehicle parked outside the restaurant one day last week, in broad daylight, looked very much like a stretch limousine. Could it be?”

Well, yes. In fact, it didn’t take long for the Page Six contingent to catch on. Fashion designers, models, actors, chefs, film directors, comely scandalettes; Diane von Furstenberg, Linda Evangelista, Daniel Boulud, Lindsay Lohan, Bill Clinton, Jack Nicholson, Monica Lewinsky, Isaac Mizrahi. “Sarah Jessica Parker had a baby shower there,” Beth Landman wrote in the New York Post. “Liv Tyler wed Royston Langdon at the restaurant, while guests Kate Hudson, Stella McCartney, and David Bowie looked on. Fashionista Lucy Sykes even went into labor while pregnant with son Felix while dining there.” Some restaurants semisecretly pride themselves on stories about customers having sex in the bathrooms. At Pastis, couples had sex on the sidewalks outside and the banquettes inside. (And had to be politely ejected, of course.) Impromptu dance parties went down. A group of people at one table got busted for shooting arrows across the room.

“Hot women,” Starr recalls. “I don’t know if we’re allowed to say that. Superattractive women and an artier crowd.” Sex and danger, art and fashion, grunge and money, steak and fries: If New Yorkers work their asses to the bone during the day so that they can float into the best party in town at night, Pastis had all the proper elements in spades. The way people talk about Pastis in retrospect, it sounds less like a restaurant than like a never-ending bender at a clubhouse where you won a lifetime membership by walking through the door. “You could go there and order a croque monsieur and sit there for three and a half hours, or you could order seventeen courses,” the editor and fashion operative Hal Rubenstein once told the writer Joshua David Stein. “You could feel comfortable eating at a table for two, or comfortable with a party of ten. You could feel comfortable in a T-shirt, or comfortable in a tuxedo. For some reason, you just felt like you always belonged when you got there, because it was a restaurant that so perfectly understood not how New Yorkers were, but how New Yorkers want to see themselves.”

Do they still want to see themselves that way? Are we still allowed to say that? Is Sarah Jessica Parker itching to return to Pastis, or will the prospect of hundreds of gawking tourists be too much for the famous to bear? And is a certain type of careless Manhattan revelry permanently on the way out after the behavioral modifications-the mass buttoning-up, the meticulous parsing of language, the handshakes instead of hugs-that have transpired in an era when social mockery and punishment can come as fast as a tweet?

Is everyone too careful now, and does anyone still care?

Or could it be that we’d have to be fools to underestimate the formidable Keith McNally? Might it transpire-as it has transpired many times in the past-that the qualities that appear to make a Pastis reboot antediluvian are the very factors that lure people into the restaurant in droves? Could the wisp of a trace of a memory of what New York City felt like in 1999 be exactly what we need right now?

Consider McNally’s thoughts on why we go to restaurants in the first place.

“I think most people go to restaurants to get away from their spouses,” he says.

With that in mind, what do some contemporary restaurants fail to deliver?

“They fail to transport people.”

When people dine out, are they more inclined to seek comfort . . . or adventure?

“Most people will say Adventure but prefer Comfort, regrettably.”

And what have you learned about human beings, over the years, from the vantage point of owning and running restaurants?

“I’ve learned that if you give a customer a drink on the house once a year, he loves you. But if you give him a drink on the house fifty-one weeks of the year, but fail to give him one on the fifty-second week, he fucking hates you.”

This story appears in the May '19 issue of Esquire.

Subscribe

What turned Pastis into a legend over time? What factors gave it its mystique?

“I’m not sure that Pastis is a ‘legend.’ One has to be outside something to be able to categorise it. I was always in the centre, too involved with putting out the day-today fires to give any thought to its possible ‘mystique.’”

With the revival of Pastis in a new location, can you match the feel of the original? Do you want to?

“Whenever we improve a standard dish at Balthazar, our regular customers, on first tasting, always complain that it’s not as good as the original dish. Only if they’re willing to try it again can they be really objective about it. The better one knows something, the more critical one is of its successor or imitator. No matter how great Pastis looks, or how delicious the food is, I’m sure lots of its former customers will, initially, be disappointed. But, ironically, I think those who were never there before will really like it. But perhaps I’m wrong. I usually am.”

('You Might Also Like',)