‘It reminded people what cities can be.’ The Contemporary Arts Center celebrates 20 years

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of The Enquirer’s Future of Downtown series.

A time traveler from 50 or 100 years ago would find plenty of corners in downtown Cincinnati today that would feel homey, or at least familiar. But the northwest corner of Sixth and Walnut streets might leave the traveler puzzled. What is that building?

Opened 20 years ago, the Contemporary Arts Center remains as surprising as ever and even more important for Downtown’s future.

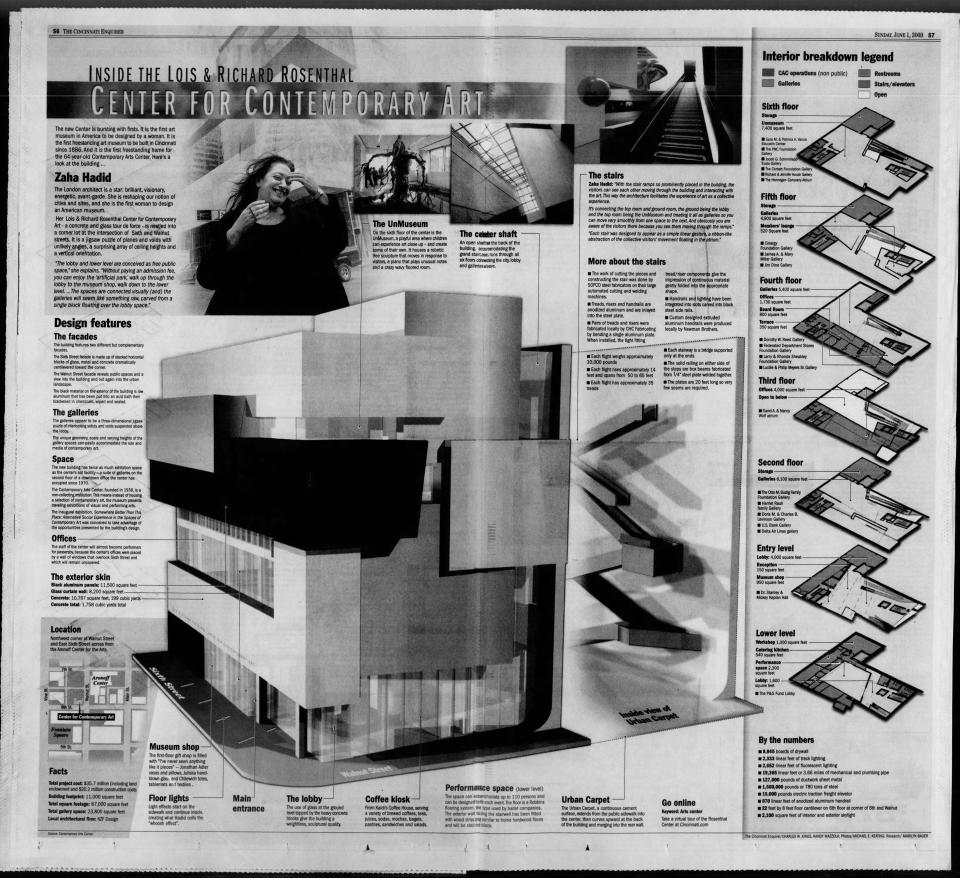

On what was once the site of a Hustler store and a hat shop, the museum brought Cincinnati international praise. Designed by Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid, it was called by the New York Times the most important American building since the Cold War. The following year, Hadid became the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize, the highest honor in architecture, despite the fact that this was only her third built project.

It also gave the center, then an established, 64-year-old institution, its first freestanding home. Two decades later, the center has drawn in 55,020 visitors through the year ending in August, exceeding its pre-pandemic attendance from the same period in 2019.

The $34 million project (roughly $57 million in today’s dollars) was such a big deal for the city that The Enquirer dedicated eight pages of a Sunday spread in June 2003 to its opening with the headline, ”A Center With Impact.” One reason for its impact was the timing, coming after the civil unrest of 2001 and the national attention it brought, added Brendon Cull, president and CEO of the Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber.

”At that time, there were still questions about what the future of the city was going to look like,” he said. ”Then enter Zaha Hadid and this building in the heart of downtown. For this community’s psyche, the center was a hugely important investment in 2003 because it reminded people what cities can be, places for creativity, art and culture.”

On view at the Contemporary Arts Center, or CAC, is a special, 20th-anniversary exhibition examining the impact of the 82,265-square-foot building. ”A Permanent Nostalgia for Departure: A Rehearsal on Legacy With Zaha Hadid” brings together eight artists who conceived site-specific installations in response to the center’s architecture and the life of the architect herself, who died in 2016.

To fully understand the building’s legacy in Downtown, it’s important to know what came before it.

Decades in the making, restaging downtown’s arts district

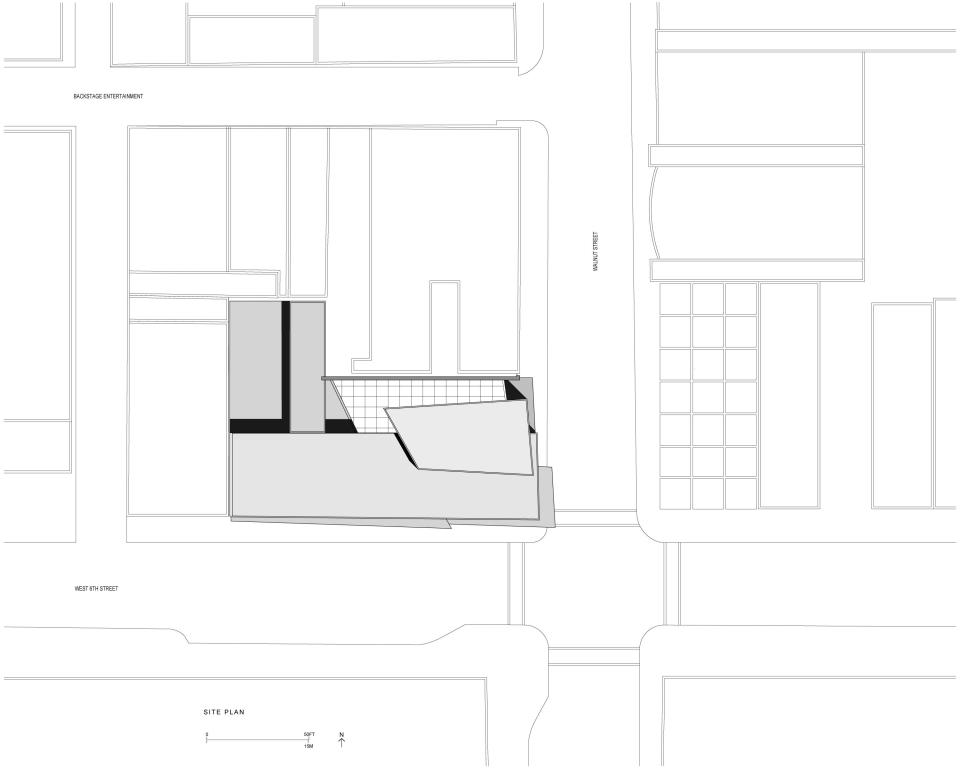

The transformation of the area around Sixth and Walnut streets into an entertainment and arts district took several decades.

In the 1940s, palatial movie houses decorated every block, but most had closed by the 1970s amid urban decay. The Times Theater on the northeast corner, for example, was turned into an Arby’s. The swanky Hotel Metropole at 609 Walnut St. had opened in 1913, but in the 1970s was converted into low-income apartments.

Plans for an entertainment district on the northeast block of Sixth and Walnut emerged in the late 1980s, culminating in the opening of the Aronoff Center for the Arts there in 1995. The Backstage District, with restaurants like Nicholson’s Tavern and Pub, followed.

Meanwhile, the Contemporary Arts Center was looking for a new permanent home. Founded in 1939, the CAC had been on the second floor of the Formica Building on East Fifth Street since 1970, but there was no street-level access and no visibility. The museum itself had achieved national attention for hosting the Robert Mapplethorpe exhibit in 1990; the explicit photos sparked protests and even indictments for obscenity. Ultimately the museum director, Dennis Barrie, was acquitted in a victory for the First Amendment.

“I think it elevated the institution in a way, because it fought for its right to be a catalyst for what’s new and what’s next and what’s important and what people are thinking about and what’s going on in culture,” then-museum director Raphaela Platow told The Enquirer in 2015.

It was expected that the CAC would take over the northwest corner of Sixth and Walnut, but the city dragged its feet until pornographer Larry Flynt stirred things up.

The Hustler magazine publisher had been eager to poke Hamilton County in the eye for charging him with pandering obscenity in 1977 (his conviction was later overturned). In 1997, he opened the Hustler adult bookstore in the former King’s News shop, right in the heart of this multimillion-dollar entertainment district.

“Odd as it may seem, Larry Flynt is acting as the missing catalyst for action downtown,” Enquirer columnist Cliff Radel wrote in 1997.

The city bought up the properties to move the CAC to the spot. Hustler was evicted, but the famous Batsakes Hat Shop, upset over the city’s offer of just $20,000 to relocate, filed a federal lawsuit to stop eminent domain. After a legal battle, the hat shop moved to the Terrace Plaza Hotel building, but the family’s dry cleaning business next door closed.

The CAC’s new home, the Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art, opened in 2003, giving the arts district its second anchor after the Aronoff Center. The Metropole next door was finally spruced up with a $48 million conversion into the boutique 21c Museum Hotel in 2012.

Do buildings have legacies?

Hadid, the first woman architect to design an art museum in America, flipped the script on traditional museum architecture, which often featured heavy stone, columns and grand entryways. She did this by using cubed, cantilevered concrete − an unusual material for a downtown Cincinnati building − and a glass base to soften it at the street level.

Michael Kelley is the vice president and director of interior design at KZF Design, the local architect of record charged with taming Hadid's vision. He argued that adding glass and making the first floor transparent to passersby was key to ensuring the building’s longevity. “People thought it would be brutalistic, heavy,” he said. Instead, the first floor of the seven-story structure is visible to everyone passing by.

To Hadid, designing the center in this way was integral to “rejuvenate the downtown,” she told Charlie Rose in a 2003 interview. “It was very clear from the beginning that you have two jobs to do,” she said. “One to create a museum space, and one to clearly make the urban connection very, very important and very strong so that urbanism is kind of pulled into the building ... so that ground space is really an extension of the city ... .”

That translates to the inside seamlessly. Instead of feeling dark and cold, its core is bright thanks to a light well that casts sun onto a black staircase that zigzags from floor to floor on the north side of the building. The galleries aren’t just white boxes either − they are adjustable and some receive natural light. Hadid’s “urban carpet,” a continuous, curved concrete wall that extends from the Walnut Street sidewalk through the lobby, is massive but not daunting. It blends in with the street and invites people into the museum.

“Even today, the building is completely flexible,” Kelley said. “You wouldn’t think that because the rest is drywall and concrete, but the thing is that the center doesn’t look abused after twenty years. It looks well-used and well-loved.”

What also takes away from the center’s would-be imposing nature is its compact footprint: The site is only 11,000 square feet and surrounded by bigger buildings. Next door, both Center at 600 Vine and the Fifth Third Center are 30 stories tall, while the Aronoff Center commands almost the entire block across Walnut Street.

It’s an approachable piece of architecture, explained “A Permanent Nostalgia for Departure” guest curator Maite Borjabad López-Pastor. “It feels like a museum in the presence and power that it claims from the street, but at the same time, it’s one of the most domestic spaces I’ve ever curated in,” she said. “To be able to be both things at once is very different, very difficult and very radical. When you walk by it, you feel entitled to enter.”

Building for the future

Part of the center’s efforts to preserve its legacy is to reduce its carbon footprint in downtown Cincinnati. The Contemporary Arts Center is a member of the Cincinnati 2030 District, a group of public and private groups committed to reducing their building’s energy use by 50% by 2030. Kroger and the University of Cincinnati are also members.

The property is currently undergoing an energy audit using money from a climate initiative grant it received last year from the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation. Using the results of the audit, the center will lay out its new goals to improve its own building systems, increase staff and visitor inclusion and diversity, and repurpose exhibition materials in its upcoming strategic plan set to be released next year.

To Shawnee Turner, the museum’s director of interpretation and visitor experience, that vision includes making the museum’s programming more accessible to a wider range of visitors.

Children are a big part of that equation. In 2021, the center completed a $5 million overhaul of its sixth floor into the 10,000-square-foot Creativity Center, which includes the interactive UnMuseum. Despite opening when museum attendance was low, the number of guided tours for area schools and homeschoolers has increased by 19% since 2022, well above pre-pandemic levels.

Overall visitation at the CAC has also improved significantly over the last two years as the city has reopened. “A lot of that is because we were downtown,” she added. “We are very dependent on downtown commerce.”

The pandemic also forced Fausto, the museum’s in-house restaurant, to close after just three years of business. A coffee shop with Deeper Roots blends and a snack bar now sits in its place, which the center aims to have open five days a week starting soon. Nearby eateries like Nada, Metropole, Prime Cincinnati, Sotto and Boca support the arts district, too.

Now, as the Contemporary Arts Center looks toward its next 20 years and tries to create a more inclusive environment for its visitors, the sweeping physical changes coming to downtown Cincinnati can only help support it, both Turner and KZF Design’s Kelley believe. Redevelopments like The Terraces and the Mercantile Center will bring much-needed living spaces, alternative food options and retail, such as bookstores or clothing stores, to the core of Downtown.

“Can we achieve something like the center again? Selfishly, yes,” Kelley said. “If it were designed well and programmed well. Seeing activity in one building should lead you to the next one because a good building is designed not just for itself, but for those around it.”

Celebrate the CAC’s 20th Anniversary

“A Permanent Nostalgia on Departure: A Rehearsal on Legacy with Zaha Hadid” will be on view through Jan. 28, 2024. Participating artists include Rand Abdul Jabbar, Khyam Allami, Emii Alrai, Hera Büyüktaşcıyan, Andrea Canepa, Zaha Hadid, Dima Srouji, and Hamed Bukhamseen and Ali Ismail Karimi of Civil Architecture Studio.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center: How it was built, what’s next