Remembering Action Park, New Jersey's Deranged Theme Park, "Where You're the Center of the Accident"

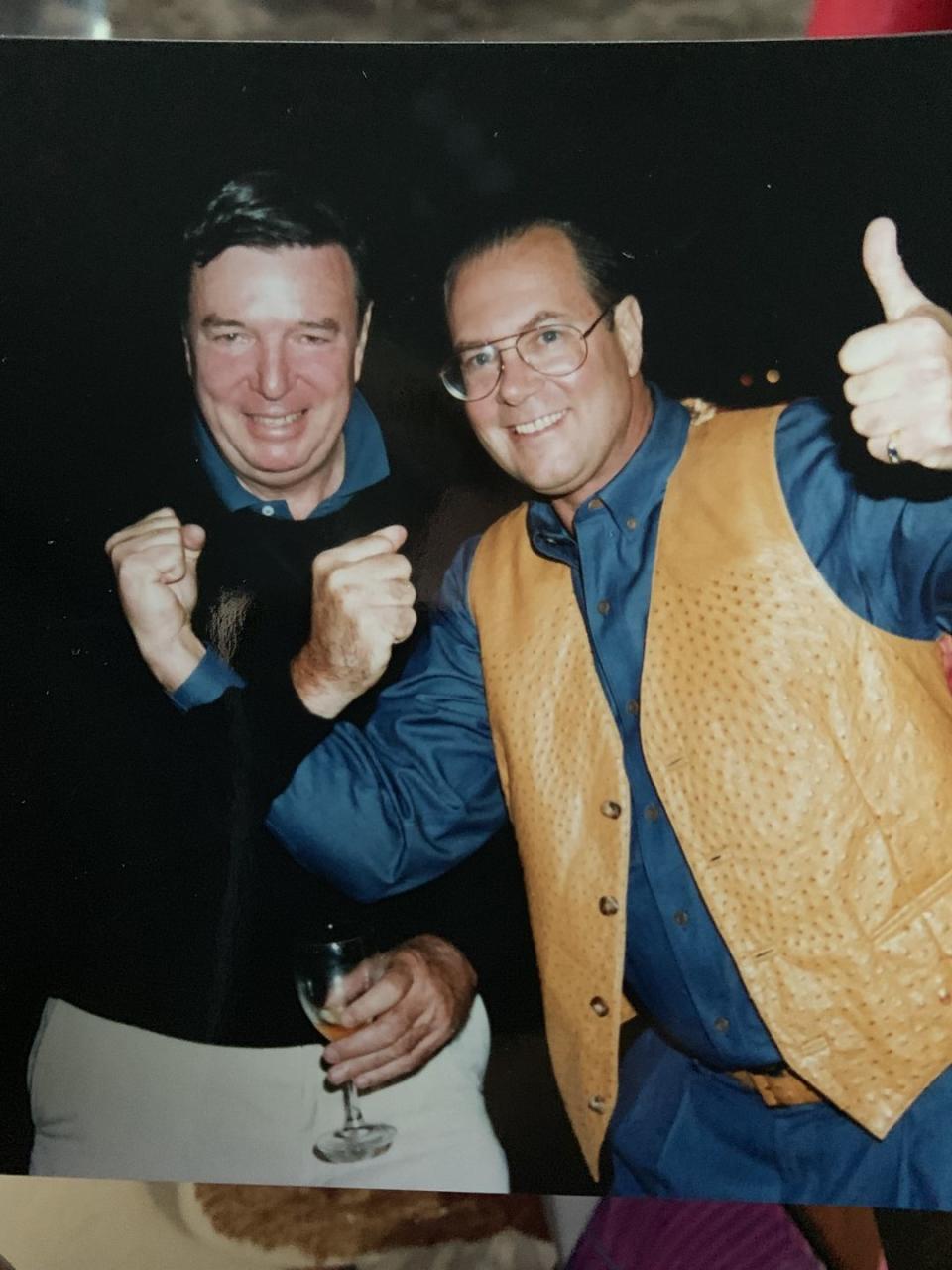

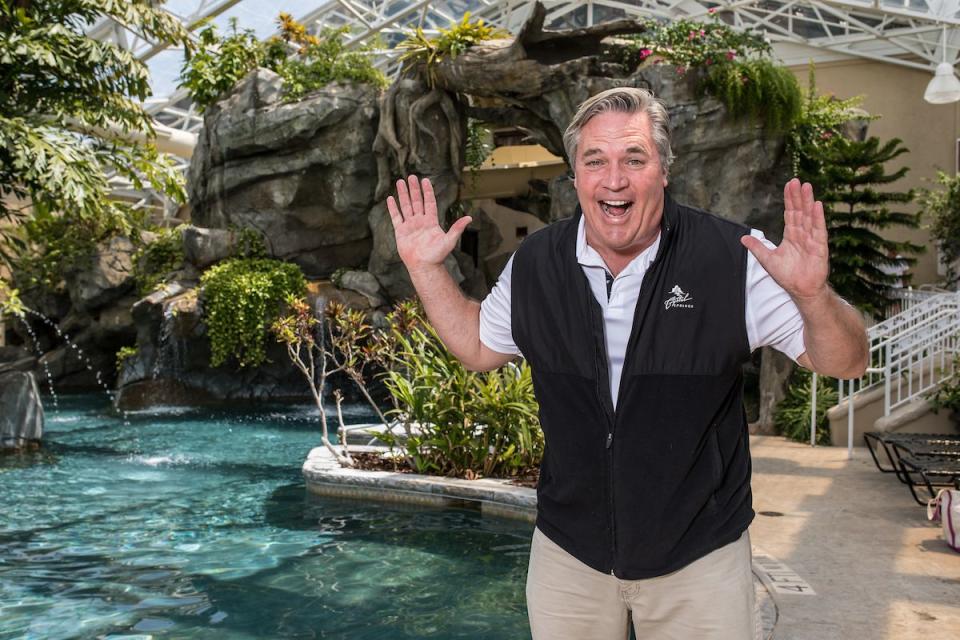

My father's name was Gene Mulvihill, and, before he opened Action Park, he had no experience of any kind running an amusement park. In contrast to Disney's carefully-conceived fantasy lands, my father pieced together a series of ambitious and often ill-advised attractions on the side of a ski mountain in rural New Jersey that he had come to own virtually by accident.

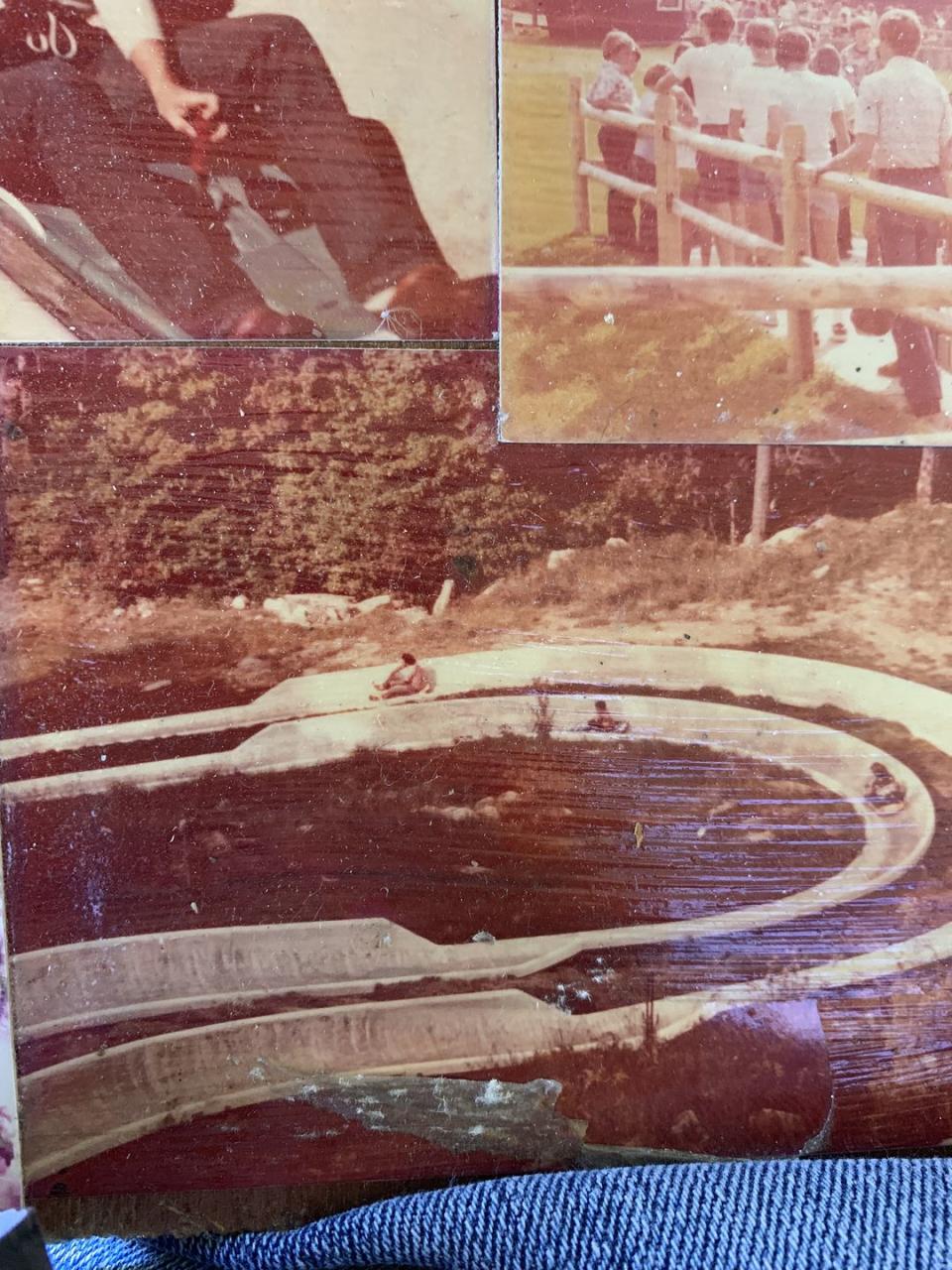

He started slowly, installing go-karts, small-scale Formula One racers, and unusual contraptions developed in West Germany with no demonstrable history of safe operation. Then came the water slides, speedboats, and Broadway-style shows. The crowds grew from a handful of curious locals to more than a million people annually. We went from selling off-brand soda and taking out local newspaper ads to getting a Pepsi sponsorship and seeing our logo on McDonald’s tray liners. My father, who had simply wanted to find a way to make money off a ski resort in the summer, found himself an unlikely pioneer in the amusement industry.

Unlike most theme parks, Action Park did not strap in patrons and let them passively experience the rides. A roller coaster, thrilling it may be, asks nothing of its occupants, and each ride is the same as the last. My father seized upon the idea that we were all tired of being coddled, of society dictating our behaviors and lecturing us on our vices. He vowed that visitors to Action Park would be the authors of their own adventures, prompting its best-known slogan: “Where you’re the center of the action!” Guests riding down an asbestos chute on a plastic cart could choose whether to adopt a leisurely pace or tear down at thirty miles per hour and risk hitting a sharp turn that would eject them into the woods. They decided when to dive off a cliff and whether to aim for open water or their friend’s head. They could listen when the attendants told them to stay in the speedboats or tumble in the marsh water and risk getting bit by a snapping turtle.

It was not long before our visitors reworked our advertising to better reflect their experiences: “Action Park: Where you’re the center of the accident.”

The risk did not keep people away. The risk is what drew them to us.

Their cars emerged from the Lincoln Tunnel, from Newark, New York, and New Haven, a chain of impatient day-trippers blaring their horns as traffic backed up on the tiny two-lane roadway leading to the property. After screaming at the parking lot attendants scrambling to keep up with the incoming masses, they burst out of their vehicles and flew past the ticket window, flashing their frequent-visitor discount cards.

In those searing New Jersey summers, they quickly stripped out of their Sasson jeans and down to their bathing suits, young men and women alike, gleefully crowding around rides while Bruce Springsteen and Southside Johnny blared through pole-mounted loudspeakers, the soundtrack for their contusions. They careened down towering water slides that spit them into shallow pools at such velocity that they sometimes overshot and landed in the dirt, laughing or bleeding—often both. They lost their grip on swinging ropes and plunged into freezing mountain water that made their bodies seize up in shock while their friends cheered on their encroaching hypothermia. They emerged from lakes stinking of spilled diesel fuel from the overworked boat motors, too delirious with enthusiasm to realize that they were now flammable.

In their haste to get to the next attraction, people would stumble and skin their bare knees or elbows. Undaunted, they would straighten themselves up and continue, too caught up in the excitement of the place to worry about a few bruises. Repeat visitors stuffed their pockets with Band-Aids and sported scabs and scars along their arms and legs. The fourteen-dollar admission bought them an escape from the mundane, from the rules and regulations forced upon them by their bosses, teachers, or parents.

“People like not being restricted,” my father told reporters who inevitably asked why his customers were bleeding. “They want to be in control.”

His philosophy became the park’s identity. My dad didn’t have the budget to stand out from an increasingly crowded amusement industry. He set himself apart by promising guests they were in charge of their own thrills.

That approach made us national news. The New York Times called my father’s creation “the area’s most distinctive expression of the amusement park in our age.” They also called it a “human zoo.” Both of these things were true.

The park yanked my siblings and me from idle adolescence and tasked with corralling and protecting the guests who took its promises of risk to heart. Other kids worked at fast-food restaurants. We spent fourteen-hour days wrangling adults and saving lives. We bonded over the outsized responsibilities, the park morphing from a playground for paying customers to our second home. Two of my brothers met their wives there. I spent ten summers walking through a tangible manifestation of my father’s psyche, every ride and attraction a tribute to his impulses. I bled into the dirt as it erupted around me. I watched it grow from a small assembly of modest attractions to a sprawling adventure land that even the mighty Disney attempted to emulate. I pulled gasping swimmers from churning water. I patrolled the grounds on a dirt bike, becoming my father’s eyes and ears. I found my first love. I forged lifelong relationships. I saw death. I grew up.

Action Park has become a campfire tale, an urban legend, a can-you-believe-this snapshot of our culture that seemed to pre-date liability laws and lawyers. The state of New Jersey had never seen anything like it and had little idea how to control it. My father loomed large in the small town of Vernon, keeping hundreds of people employed and using his political savvy—as well as his sometimes-questionable legal means—to make sure his passion project remained afloat. Other parks would get fined or threatened with shutdowns when guests stubbed a toe. Action Park remained open for twenty years despite injuries being a near-hourly occurrence.

The price for its success was sometimes paid by visitors, not all of whom came out alive, and sometimes by my father. The state once held a three-day hearing to discuss his outlandish approach to business and how best to deal with him. I'm pretty sure that never happened to Walt.

It was a place that admitted anyone, misfits to clergymen, rich and poor, young and old, and told them it was theirs to do with as they pleased; never again would they have such freedom in their lives. The churn went on all day, people bouncing from the miniature race cars to the Colorado River Ride to the Kamikaze slide. Come closing time, at 10:00 p.m., they’d reluctantly head to their cars, making plans to return while showing off their scrapes and abrasions. Back home, exhausted and exhilarated, they would grab a pair of scissors and cut off the plastic wrist strap that acted as proof of admission.

It looked almost exactly like a hospital bracelet.

Like soldiers taking the beaches of Normandy, hundreds of people poured into the Wave Pool when it opened on Memorial Day weekend. The manufacturer, WaveTek, had a recommended capacity, but no one knew the number. It was listed somewhere in the phone book-sized operator’s manual my father had thrown into the corner of his office, disinterested in its annoying limitations.

Whatever the tally was, we were clearly in violation of it. The Jersey Shore had an unlimited expanse, offering each visitor their own private oasis away from everyone else. The Wave Pool packed attendees in with such congestion that people were practically elbow-to-elbow. Previously, Water World’s only bodies of water were small pools that held just one or two people coming off a slide. Here, there were hundreds packed in with such congestion that you could’ve walked on their heads like a frog hopping on lily pads and never have to touch the water. The pool was so enormous that you couldn’t have a conversation with anyone on the other side of it.

Unlike our other rides, there was no specific entrance. People dove in from anywhere, splashing into the shallow end or sinking like stones into the deep end. Most tended to come in on the right side, since that was closer to the pool-area entrance. They jumped into water that was just deep enough to cover their head or neck, unprepared for the waves battering their faces. This area was immediately designated the Death Zone by Smoke, who nonetheless took up sentry duty and paid close attention to signs of trouble. He did this even as Lynette and Denise filled his peripheral vision, their clingy red suits tight enough to look like a second skin.

The waves were on a timer—twenty minutes on, ten minutes off—to give swimmers a break from their pummeling aggression. We had a digital countdown display, similar to a scoreboard, that let people know when the waves were coming. If they got in during a lull, they happily paddled about with a false sense of security, some sitting on tiny rafts, mats, and inner tubes rented out at a stand nearby.

When the waves hit, their force caught our guests unprepared. Powered by the insulation-sucking fans, the waves struck with the same violent menace originally meant to create a series of mini-shipwrecks. Most people in the flotation rentals capsized. Devoid of their occupants, the tubes looked like soggy Cheerios floating in milk. The canvas rafts, made to hold one person, were often overstuffed with three or four. They were also prone to trapping people underwater, plugging the limited space between swimmers and preventing anyone from surfacing. If one occupant went under, the others would try to help. Pretty soon, the small party would all be in peril.

“I can’t see shit,” Smoke said, angling for a better view through the sea of people and the still-murky water. “Fuck. Look at that guy.”

Smoke pointed to a broad-shouldered teenager waving his arms and bobbing in and out of the water. I got Lynette’s attention, and she jumped in to help, only for the guy to suddenly break into a grin, flip his middle fingers, and cut underneath the surface like a dolphin. He was in no trouble.

“Asshole,” Smoke seethed.

By noon, the congestion began spilling out into the margins of the pool. The wraparound deck was full of people tugging their dripping swim trunks over their exposed cracks. Others dove in without bothering to remove their sweatpants or jeans. Children ran laps, the wet concrete threatening to send them sliding into a leg cast. Teenagers with gold chains around their necks scanned the pool, looking for friends. When they found them, they would dive in with the express goal of landing on someone’s head. Their target would resurface, distributing headlocks in retribution.

The waves produced an anticipatory, nervous energy. Pushed by the fans via massive air vents—it was like a network of leaf blowers—the water rose more than three feet above the surface, looming over its victims and appearing to pause before collapsing on top of them. Instinctually, people put their arms over their heads or turned away. It made no difference. Few could remain standing if they were in the waist-deep areas. Without a firm footing, they’d be carried away. The waves abruptly cut off conversations.

“I’m thinking of taking the boys to—OMPHLEGGHM,” one woman said, unable to finish her thought before being claimed by the pool. It was like watching the Rapture.

We were all armed with buoys, ring-shaped chunks of high-density foam that we could toss to people having trouble with the tide. By the end of the day, we had used them all repeatedly, not realizing that they had absorbed water and developed the density of a brick. When one hairy-chested occupant struggled to swim against the current, Vinnie tossed him a waterlogged buoy. His powerful arms made it sail like a Frisbee. It landed just as the swimmer was surfacing, smacking his face and shattering his nose.

“Gahhhh!” he cried.

Consumed with their own struggles, no one in the pool paid him any mind. I waded in and escorted him out and to the infirmary, tiny red droplets leaking from his face and dotting the pathway.

Smoke made our first dive-in save, dragging a swimmer who had been tossed out of his raft by the waves and left to flail in the water. Smoke got him to dry land immediately. I exhaled in relief. This is manageable, I thought. Everything will be okay. Action Park is “like, whoa,” but that’s all.

Then came another. Lynette jumped in. Then two people began going under at once. Smoke pulled a man out as another began panic-paddling right next to him. Dragged beneath the surface by the hysterical guest, Smoke began punching him in the head to make him loosen his grip. The mood had become manic. From that point on, none of us was ever out of the pool long enough to dry off. Vinnie Mancuso didn’t bother sitting down the rest of his shift. I saw fear in some of the guards’ eyes. They were exhausted and scared, the full weight of the responsibility beginning to slump their shoulders. A summer job had turned into a struggle to keep people alive.

There was no B squad. We all worked from 10 a.m. to sunset that day, eating lunch on our feet, our arms scratched from people clawing at us as we wrangled them to the deck. I started interrogating the rescues, searching for evidence of some kind of misunderstanding or defect. Something we could fix.

“Why did you go under?” I asked one man. A soggy Van Halen shirt clung to his protruding stomach. “Are you okay in the water?”

“Yeah,” he said. “I’ve been in the Central Park fountain.”

A boy came up to me. “Mister,” he said. “How deep is the water?”

“Over your head,” I said. “Don’t go in.”

I turned around. When I turned back, he was upside down in a tube, legs pumping in the air like he was riding an invisible bicycle. I pulled him out. “What happened?”

“You’re supposed to pull me out before I drown,” he said.

“You need to be more careful,” I said, a paternal hand on his shoulder.

“Eat a dick,” he said, and dived back in.

A horrible realization came over me. The Wave Pool’s occupants had taken on a collective, stupid consciousness, one that paid no mind to the threat of drowning. The commercial had sterilized the park. Nothing on television could be hazardous. Nothing could happen to them.

With the water cloudy from body oils, suntan lotion, and other excretions, it was impossible to peer over the edge of the pool and see the bottom. After we finally ushered everyone out, I dove in and made two passes, convinced I was going to find dead bodies that had been obscured by the filth. Thankfully, there were none. Satisfied I did not have to summon the coroner, I went directly to my father, who was reviewing attendance numbers.

“Eleven thousand people,” he announced. “That’s twice our best day!” I had witnessed it first-hand but had not been able to process the math. A blast of furnace-hot weather, Wave Pool hype, and the commercial had colluded to create a surplus of humanity.

I collapsed into his leather office chair, exhausted from the heat and exertion. “We got a problem,” I said, waiting for him to look up. He didn’t. I explained that, if we couldn’t see the bottom of the pool, that meant we couldn’t see any people at the bottom of the pool.

“Andy,” he said shaking his head. “You can’t see the bottom of the ocean, either.”

“So?”

“So, that doesn’t mean you stop people from swimming in it if they want.”

This was Gene Logic, which used nature to explain why things weren’t really as dangerous as I feared they might be. Sure, you could fall off the Alpine and crack your head open, he’d say. But you can also get into a car accident on the way to the park! Don’t go outside, you might die of a bee sting! Come on! People want to have fun!

I wanted to point out that the concept of acceptable risk includes understanding the risk, which was not necessarily the case with the pool and its unique method of assaulting people with water. In my weary and sun-stroked state, I just mumbled something about limiting the number of swimmers going in at once and having a designated point of entry. These seemed like small but manageable victories.

“We’re not making people wait in line,” he said. My father hated lines. They reminded him of the DMV.

“Then let me turn the fans down,” I said. “At least let me do that.”

“I would make them stronger if I could,” he said. “I’m gonna ask the design people about that.” He looked around his office. “Where’s the operator’s manual?”

The next day we upped the chlorination in the Wave Pool to cut through the oily sheen on the surface. We became amateur chemists, mixing calcium chloride with baking soda without any real idea of how to filter such a massive body of water. On days we got it wrong, kids would emerge from the pool wincing, their eyes red with irritation. For ten hours, we performed a ballet of rescue and retrieval, dragging out and admonishing people who came out sputtering after nearly being killed by their own lackadaisical attitude. Because the countdown display had gone unnoticed, I tried using a bullhorn to announce when the waves were coming. It merged into the tinny sound of the speakers blaring “Celebration” by Kool & the Gang on an endless loop and was ignored by all.

At the end of the long weekend, Julie and I held a meeting of the lifeguards. We sat around a cafeteria table in silence. Vinnie Mancuso kept his head down, starting at the skinless chicken he hadn’t had time to eat.

“You guys did great,” I said. Lynette was sobbing.

“We need to shut this fucking thing down,” Smoke said, black circles around his eyes.

“I know what the problem is,” Julie said, her face adopting the emotionless gaze of middle management. It startled me. “We had a lot of church groups that got bused in from the Bronx this weekend.”

“We get buses every weekend!” Smoke shot back. “The bottom line is, New Yorkers cannot fucking swim! These are land people!”

We talked about all the things my father was not going to do, like force people to wait in line. We discussed the drunk who had scalped himself diving into six inches of water, briefly clearing one end of the pool as he bled into it like a shark-attack victim. Julie refused to entertain the idea of a raise from three dollars and ten cents an hour to accommodate the psychological toll exacted by the job. We agreed that no more than two people should share a raft, and that we probably needed a sign cautioning people about the waves. Doug Rounds recommended everyone get hepatitis shots.

“The commercial is going to keep running,” Julie said. “So, I mean…” She looked at me. “It’s probably going to get a lot busier.”

At the end of the meeting, two people threatened to quit. I begged them to stay. The next day, Tommy Smith took to scrawling the letters CFS on the admission bracelets of people who had been dragged from the pool.

“What does that mean?” I asked, watching one such guest bounce to another area of the park.

“Can’t Fucking Swim,” he said.

From ACTION PARK by Andy Mulvihill and Jake Rossen, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (C) 2020 by Andrew J. Mulvihill.

You Might Also Like