The ‘Rah Rah’ Never Left: Busta Rhymes, Mayor of Hip Hop

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

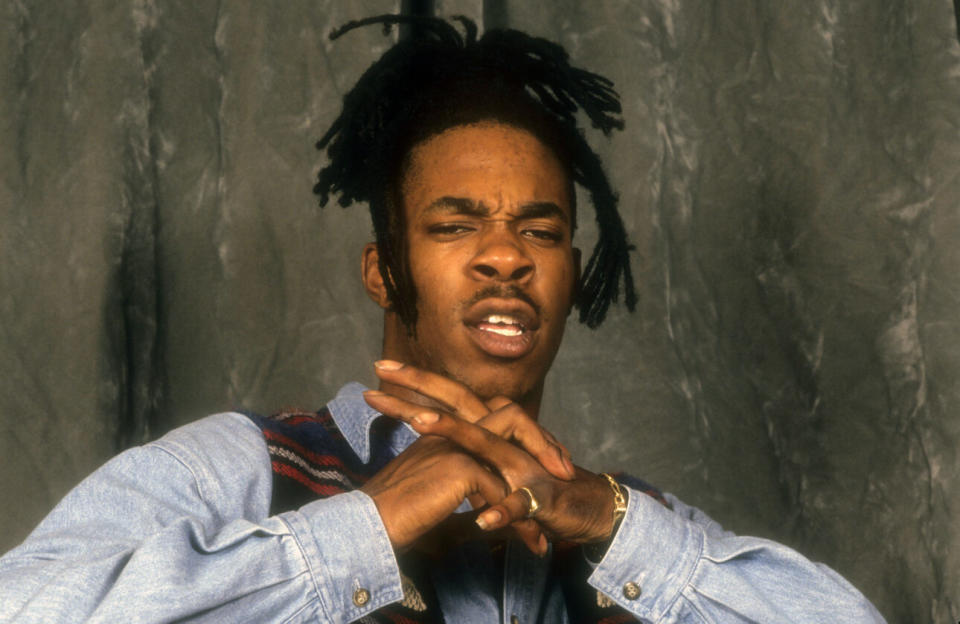

“I’m a real giver of love. I might overwhelm you. I’ll want to hug you and not let you go,” Busta Rhymes tells the audience at the 2023 BET Awards this past June in his trademark, bellowing staccato. It belies an awe-striking physical presence — 6’1” and a muscular 255 lbs., a custom double-breasted floral tuxedo with metallic lining and a 54mm Cuban link chain comprised of 10,000 diamonds — but the man born Trevor Smith Jr. is giddy to celebrate his Lifetime Achievement Award.

The award show was inevitably going to choose a prolific rapper to honor the 50th anniversary of hip hop, but the New York native knows it could’ve gone to any one of his deserving contemporaries. He beams as Pharrell Williams likens his flow on the mic to Louis Armstrong with the trumpet. Janet Jackson and Mariah Carey blush as they reminisce. Diddy calls him “the mayor of Hip Hop,” and 10 minutes later, as if he were fatefully tasked with warding off any emeritus allegations, Busta salutes Ice Spice and Kendrick Lamar in the same breath. His voice swells up as he eyes his eldest son T’ziah, now 30 years old but etched into the music’s visual history at 3 for mugging the camera in canary yellow in his father’s first music video.

More from Spin:

For an artist widely regarded as one of the fastest rappers and most dynamic linguists to ever rhyme on wax, Busta Rhymes is unhurried in conversation. Punctuating his words with deep breaths and long pauses, Busta tells SPIN why he felt vulnerable on stage that night. After years of mourning and self-destructive behavior, he was feeling loved.

“I lost my manager Chris Lighty in 2012. I lost my father in 2014, and I buried myself in work,” he explains over the phone from his tour bus. “That allowed me to run from dealing with it, and it led to me drinking too much, smoking too much, putting excessive weight on, doing things that weren’t good for me.”

The next three years were plagued by throat blockage due to polyps on his vocal cords, inconsistent musical output and the death of another confidant and collaborator in A Tribe Called Quest’s Phife Dawg.

“So that night (at the BET Awards) I was extremely moved, watching my friends choose what they say about me to the world,” he continues. “When these gigantic superhumans are acknowledging you, it’s indescribable, because you’re usually not around for those conversations. I might’ve felt like I was worthy of these flowers in prior years, but hip hop allowed things to align in the way they did right now, and in hindsight, the opportunity to share my journey on the 50th anniversary of our culture is the greatest reward in the world.”

Having lost more than 100 lbs. and recently touring with Nas, Wu Tang Clan and 50 Cent, Busta’s comeback will culminate in a 2023 return-to-form album executive produced by the generational triumvirate of Pharrell Williams, Timbaland and Swizz Beatz. He raps with buoyancy and humor and says that it was the most challenging studio effort of his career aside from working with the famous perfectionist Dr. Dre in the mid-aughts. Three decades and 10 million album sales after the original powerful impact of his breakout, Busta can still smell the Chocolate Thai White Owls he rolled to invite himself into mid-’90s ciphers and major-label studio sessions. Though the veteran no longer needs to offer blunts for recording time, he’s still maintained a metaphysical connection to that time and headspace. As Busta sees it, it’s a duty to ensure that the “rah rah of the dungeon dragon” never burns out, not just for his sake but all of ours. The music exists for a greater purpose, he reasons because its origin is so precarious; an infinite list of what ifs could’ve stopped the lanky Jamaican teenager from making the “Scenario” remix.

“What if I pulled up at the wrong time? What if the receptionist I knew wasn’t at the desk, or what if the studio engineer was in a meeting or something? The way I saw it, I had nothing to lose. I could always go back to hanging at the crib or on the corner,” Busta says. “But I listened to that voice in my head, and as a result, I was riding around hearing myself on records, which would’ve never even been released if I didn’t crash the session.”

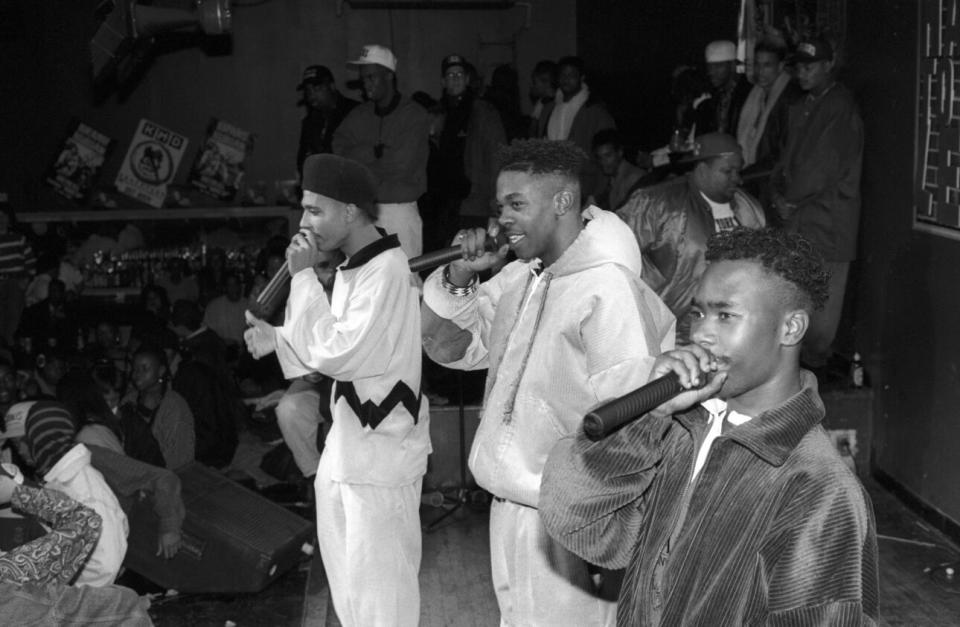

Despite his magnetic flow and charisma, Busta’s best asset back then was his willingness to learn from others. Chuck D gave him his stage name as a member of Leaders of the New School, an opening act for Public Enemy. He practiced rapping at a Long Island home owned by EPMD, and once he felt sharp enough, showed up unannounced to Chung King, Green Street and Sony Studios across New York. With the White Owls lit, the rah rah was born. Busta built instant hype with his song-stealing verses — not just “Scenario” but on joints with Brand Nubian, Big Daddy Kane, KRS-One and TLC.

When Leaders of the New School disbanded due to infighting in 1993, it was Lighty’s Violator Management that pushed Busta Rhymes as a solo artist. Expectations for his career were tough to project since Busta was known exclusively as a collaborative emcee and rarely did more than 16 bars per feature. But his 1996 Elektra Records debut, The Coming, reached No. 6 on the Billboard charts and went platinum on the strength of two diametrically different singles — the claustrophobic surrealism of “Woo-Hah!” and the Zhané-backed minor key groove of “It’s a Party.” The Coming housed some of J Dilla’s earliest production work, then credited as The Umma with Q-Tip, and the Dean Karr art direction married cloudy, distorted soundscapes with the emcee’s unique freneticism. A year later, Busta went platinum again for When Disaster Strikes, refining his delivery while sneaking elements of Afrofuturism and end-of-millennium dystopia into club-ready smashes like “Put Yo Hands Where My Eyes Can See.” His first five solo LPs reached platinum certification.

Busta Rhymes’ ascension as a hip hop icon can’t be understood merely through the music itself. As the art form’s visual language increasingly took on two main corollaries — the bigness, nice cars and luxury mansion parties of Bad Boy/Death Row, and the minimalist street corner rapping of Native Tongues and The Pharcyde — Busta created a wholly original and stunningly visceral style of music video. ”Put Yo Hands” recast Coming to America through a fisheye lens while Busta played both Prince Akeem and the Devil himself; “Give Me Some More” was a compressed mushroom trip in comically oversized outfits; “What’s It Gonna Be?!” saw him emerge from liquid plasma, marshall a silver marching band and successfully court an amethyst-dipped Janet Jackson. Ten years after his debut, Busta Rhymes had his first U.S. No. 1 album with 2006’s The Big Bang Theory. In celebration of how his own career took shape, the lead single “Touch It” featured five different remixes, including one with only women rapping. Meanwhile, the Dr. Dre-produced closing song, “Legend of the Fall Offs,” was a direct meditation on his longevity in hip hop and the breaks of the game felt by many of his peers.

“When I look back, I’m really just glad I found something I love this much. I’m still so passionate about this thing 32 years in as a professional, not only for what it’s done for me but for those around me,” he says. “Going in chronological order, the way things have played out for me, I wouldn’t want it to happen any differently and I wouldn’t change anything. And the most incredible part is, outside of Chris Lighty, all the people who played significant roles in my career are still here, receiving their flowers with me.”

One of those people is Sylvia Rhone, the Harlem-born A&R who signed Busta Rhymes to Elektra. Busta joined Rhone at Epic Records and will now be releasing just his second album since an ambitious but stunted 2012 partnership with Cash Money and Google Music. The first new single, “Beach Ball,” is a minimalist and sun-drenched jam featuring BIA and produced by Timbaland, recalling the era when top-level emcees were striving to rule each summer.

“The music has good energy, party vibes. There’s nothing dark, nothing conceptually too heavy, but nothing that isn’t true. On my last album [Extinction Level Event 2: The Wrath of God in 2020], I was responding to a lot going on: the pandemic, the shutdowns and riots, the police killing unarmed Black men, women and children. It was heavy, and we’re still going through it, but it’s my responsibility to also show balance. And right now, I’m on top of the fucking planet with happiness.”

The album’s title, Block Busta, originated from a conversation with Q-Tip, but Busta says Swizz Beatz arrived at the same title during a separate session months later. The project was initially conceptualized as a six-song EP with two beats each from Swizz, Pharrell and Timbaland — after the four were on a boat together in Miami, listening to the posthumous DMX album. There’s an undeniable shared history: Swizz’s first Busta beat placements were among his first-ever production credits; Timbaland has worked with him since MTV Diary; Pharrell was the one passing him the Courvoisier.

“I’m looking at these three motherfuckers, and I hadn’t said anything for four or five hours, but…we need to make a project together. No one has mentioned this all day and I’ll be damned if I don’t say something!” He also says that the final Block Busta track, called “Legacy,” will feature three of his children — who rap, sing and play piano, respectively — inspired by his evolving relationship with his kids and particularly sourced from the BET Award celebration night.

When asked about his favorite live moments, Busta brings up recent festivals overseas and an orchestral, black-tie show at Carnegie Hall. But he also details the considerably smaller 2012 Brooklyn Hip Hop Festival — scents of piff and jerk chicken carrying out to the East River; the ever-reticent Q-Tip actually being the life of the party that day; his foremost inspiration Slick Rick rocking the stage right before him; embracing Leaders of the New School’s Charlie Brown for the first time in 19 years; the crowd levitating for “Scenario.” He reflects like a man who became a solo emcee only by circumstance, a genuine collaborator in an art form that revels in competition. The “rah rah” isn’t going anywhere, because it’s collectively owned.

“I’m never too humble to say that I’m not an absolute God in this shit,” he laughs. “But the truth is, the greatness of those around me helped me realize the level of accomplishment I was capable of.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.