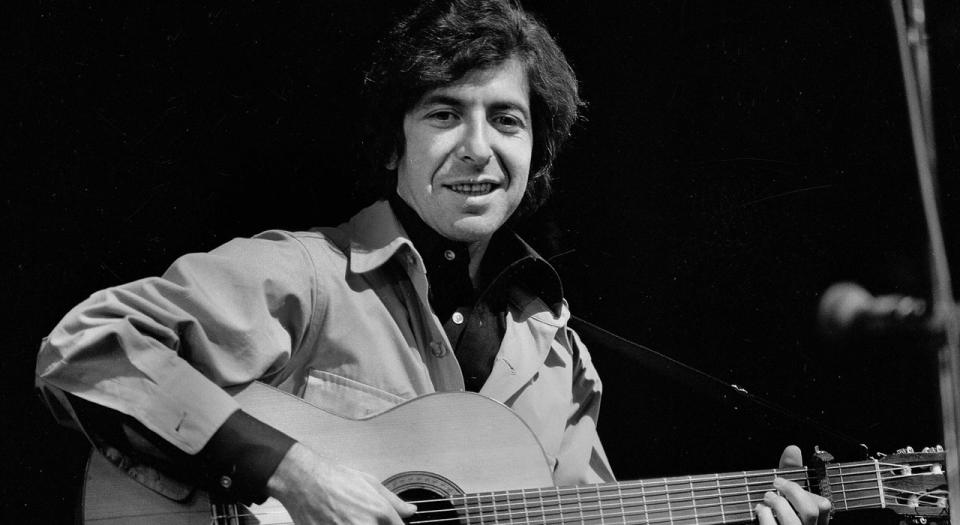

R.I.P. Leonard Cohen: The Music World Is a Little Darker

There is a respected website called Cohencentric.com which devotes itself entirely to all things Leonard Cohen, and on Thursday, the day the 82-year-old, much-loved performer died, it was headed by a black banner reading: “Leonard Cohen Is Dead / Our World Is Darker.”

There were an infinite number of ironies to be had there: Yes, the man was, unexpectedly, dead; yes, those words played on the title of his just-released album You Want It Darker; and yes, news of the man’s death punctuated a news day filled with reports of political riots across the country and dissatisfaction and angst about this week’s election.

And it was still another frightful death in 2016, the year when nearly every musician of significant value seems to have independently decided to depart this planet.

Cohen’s death hits us especially hard because there have been very few popular musicians like him, whose careers have been tied up in the arts — in poetry, in prose, in songwriting, in singing those songs — who managed to eke out a financial living and attain near-unparalleled critical respectability without the obvious struggle for a hit record, without bending his art one iota for the sake of fashion if it compromised his work. I can think of less than five, and two of them are Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell. Cohen was, truly, peerless.

Significantly, as an artist, Cohen was announced to the world fully formed in 1967 via his debut album, Songs of Leonard Cohen. Fully formed, mind you, because the album’s stunning opening track “Suzanne” had already been introduced to the world via Judy Collins’s much-heard cover on her gorgeous 1966 album In My Life. It was the first most people had ever heard by Leonard Cohen, and rather than an upbeat, tuneful announcement of the arrival of a zesty young tunesmith, it bore the hallmarks of all of Cohen’s best work: fetching melodies, minor keys, lyrics highlighted by passages of often disturbing emotional clarity and occasional redemption. “And she shows you where to look among the garbage and the flowers,” Cohen wrote, “There are heroes in the seaweed, there are children in the morning / They are leaning out for love and they will lean that way forever.” Not many people release their first album at the advanced age of 33, but Leonard Cohen did, and he already sounded world-weary.

Cohen’s career continued with a series of remarkable albums that initially featured intimate, acoustic guitar-and-vocals performances and eventually added much more. Throughout it all, Cohen was constructing songs that were filled with themes and lyrics unlike any most of us had heard: “Seems So Long Ago, Nancy” with its “It seems so long ago / Nancy was alone / A 45 beside her head / An open telephone”; his unforgettable “Avalanche,” later covered by Nick Cave: “When I am on a pedestal, you did not raise me there. /Your laws do not compel me to kneel grotesque and bare. / I myself am the pedestal for this ugly hump at which you stare.” And the jarring, unforgettable “Story of Isaac,” told from the perspective of Abraham’s biblical son: “The door it opened slowly/ My father came in / I was 9 years old.”

Ultimately, Leonard Cohen’s best work may have been most striking for a lyrical nature that can be called many things, “adult” perhaps being most appropriate. In the field of popular music, he was writing songs about topics few songwriters would ever attempt, let along credibly carry off. Cohen’s groundbreaking 1977 collaboration with Phil Spector, Death of a Ladies’ Man — which was unfairly reviled by many — bears at least one song with a conceptual hook that is jaw-dropping: “Paper Thin Hotel” details a lover checked into a hotel listening to his partner in the room next door with someone else: “I listened to your kisses at the door / I never heard the world so clear before / You ran your bath and you began to sing / I felt so good I couldn’t feel a thing.” That last line is what makes Cohen so unique.

Curious things would happen with Leonard Cohen’s career after that. Columbia Records refused to release his 1984 album Various Positions domestically because they viewed it as having little commercial potential; it contained not only one of his best songs, “Dance Me to the End of Love,” but what may be his most popular — “Hallelujah,” soon covered artfully by John Cale, then Jeff Buckley, then seemingly the entire world of reality TV. The label eventually picked it up.

And with the arrival of its follow-up, 1988’s I’m Your Man, Cohen began connecting with the general audience in a way he hadn’t previously. The album started with a bang — “First We Take Manhattan’s” memorable title and melodic hook, all over a rich, synth-heavy backing, propelled the track into the pop parlance — and ended with “Tower of Song,” a track that would become more significant in the years that followed. “I was born like this, I had no choice,” Cohen sings, “I was born with the gift of a golden voice.” He was being humorous, he was being facetious, he was letting the audience know that he realized the limits of his vocal range and… he pretty much stopped singing from that point forward.

Most of the albums that followed featured Leonard Cohen reciting his lyrics, in a voice that seemed to drop an octave per album. While it was disappointing — but wasn’t a decreased vocal range a physical inevitability of old age? — the new material was still polished, the new songs were filled with lyrics crafted with Cohen’s maniacal precision and dealing with subjects that, to Cohen’s credit, a man of his age might write about. As albums, as recorded works, they were impeccable.

While much happened in his life that has been well-recounted elsewhere — financial and personal struggles — it has to be said the latter decades of Leonard Cohen’s life were among his most visible. He was out there on the road, he was releasing records that were consistently well reviewed, he was engaging several new generations of fans — at places like the 2009 Coachella festival — and he was around long enough to not only release the new You Want It Darker, but to read the uniform rave reviews it received worldwide. The widely circulated New Yorker story by David Remnick was a wonderful account of an artist deeply appreciated by both his peers — no less than Bob Dylan was effusive in his praise — and his worldwide audience. That Cohen was around long enough to read it was likely gratifying for all parties.

No one expected Leonard Cohen to be around forever, but nobody was expecting him to bow out so soon, either. Rather than mourn his departure — which would be so easy to do — it might be in our best interest to examine his work thoroughly, all of it, and appreciate it yet again. There is a warmth, gentleness, and humor that permeates all that the man produced, and during this very jarring week, when much of our world seems to have gone awry, a listen to Leonard Cohen and You Want It Darker may shed at least a little light on things. And we need that light.