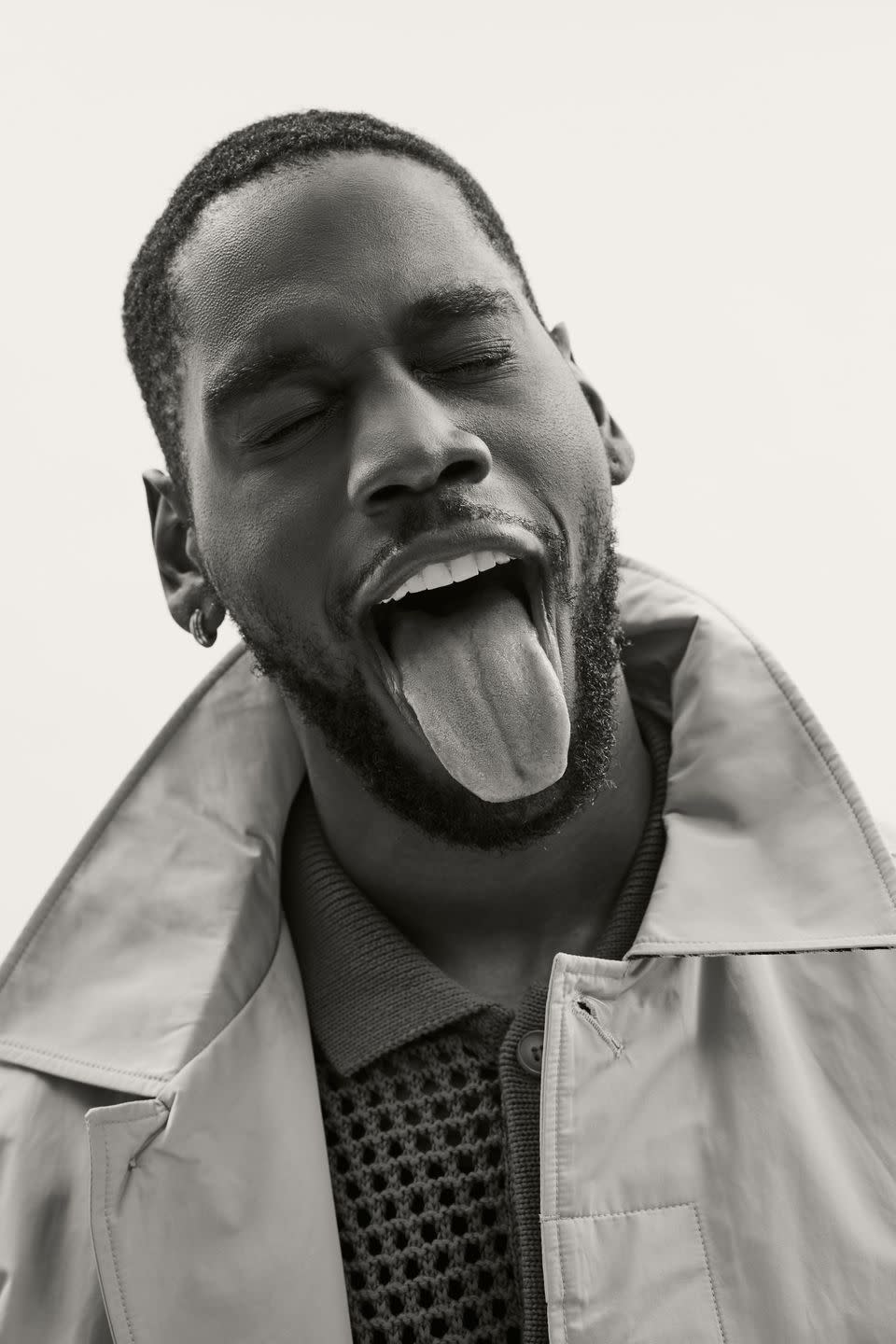

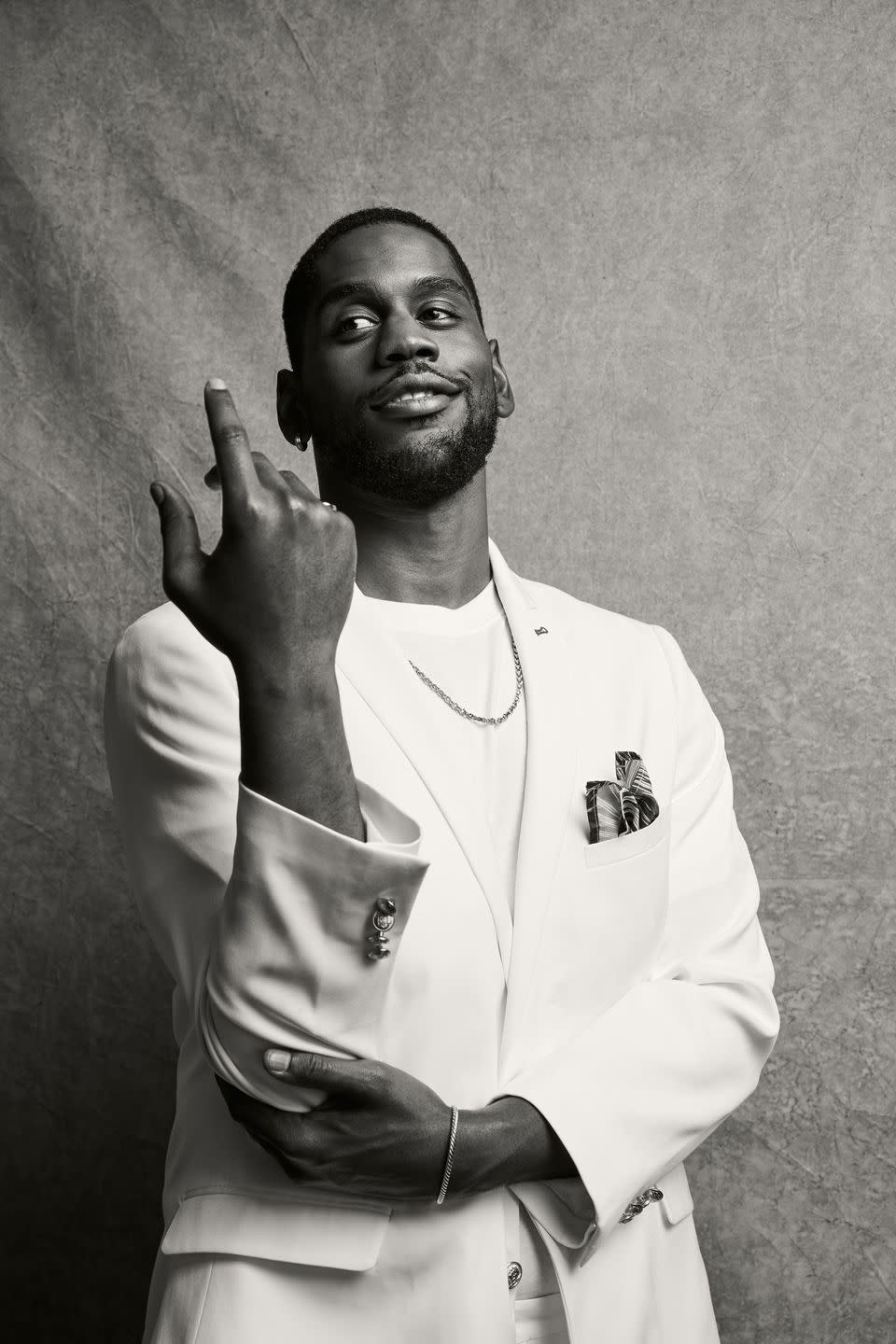

Quincy Isaiah Isn't Looking For Anyone's Approval

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There are some things that just can’t be faked. Take for instance, Magic Johnson's famous smile. It’s the grin that summed up Magic’s duende—charisma to the nth degree. He was personable, adorable, cute. Not exactly qualities that you’d usually associate with a six-foot-nine point guard. Then again, Magic was a revolutionary talent whose stardom quickly rose outside the confines of the game. He was a killer, and after his rookie year, NBA champion and Finals MVP.

But the smile won you over. Now, about 40 years later, someone had finally managed to replicate it: Quincy Isaiah, who plays Johnson in HBO’s Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty, which returns for its second season on August 6. Isaiah not only conveys Johnson’s ease and charm, but yes, he has that smile locked down. Plus, the 26-year-old may be a neophyte in the world of acting—this being his first major role—but the smile cannot be taught.

For all its stylized action and fourth-wall-breaking, Winning Time, would be a flat soufflé if Isaiah's performance didn’t ring true. Funnily enough, Season Two, which spans the 1981-’84 NBA seasons, finds Johnson dealing with the consequences of his charm—and immaturity. He suffers an injury, beefs with Norm Nixon, argues with his head coach, Paul Westhead, and deals with his own disapproving family back in Michigan. Oh, and there’s Johnson's specter of his pock-marked rival across the country; a dude named Bird, seemingly hellbent on torturing Johnson into second place.

A few weeks before Winning Time’s return, Isaiah discussed how he avoided a sophomore slump, handled public criticism from Magic Johnson, and continues to get an acting master class from John C. Reilly.

This interview was conducted before the SAG-AFTRA strike.

ESQUIRE: You went to therapy before Season One aired. As someone who is a therapy-lifer, I thought that made a lot of sense—just to prepare yourself for the public response. After Season One ended, did you go back to therapy?

QUINCY ISAIAH: Yeah. I’m still in and out. And now I go every so often. But when I’m feeling like I need to talk to somebody? For sure. It’s a tool that I use to just make sure that I’m good—it’s an accountability check. I’ve got to make sure I’m living life the way I want to be living and not the way other people want me to live.

Right, now you’re in a more vulnerable position because you’re not just Quincy, but Quincy—the guy who can do something for people. People might approach you with that sense of wanting something from you.

My thing is not about worrying about all that and just being so strong in who I am that I can’t even see that. It’s like having blinders on. I got such a good group around me. That’s the way I’m trying to move. Only positivity. That’s why I try to foster that with therapy. And in my conversations with people, and people I work with, just being honest. Make sure we’re all trying to do the same thing.

The first season of Winning Time was criticized by former Laker greats Jerry West, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Magic Johnson himself. Have you have contact with any of those guys?

Norm Nixon. I mean, because DeVon [Norm Nixon’s real-life son] is on the show.

Have you had any interaction with Magic at all?

No. No.

As an actor, you’re playing a public figure who is alive. You have to manage that line between respecting that you are portraying a real person and fidelity to the filmmakers’ vision. Especially when the person you are playing isn’t thrilled about it. How do you block out the noise?

Starting with myself. I’m leading with such pure intentions. I’m protective of all my characters. I always want them to be humans. With Magic, I’m playing a character that I feel proud about. It’s a person. And I get it. I understand where he’s coming from. That’s why I can’t ever—I don’t have any feelings about that. I just got to do my job. And it’s a good job. [Laughs.] I can’t turn that down, man. I still respect him. I still have all the love in the world for him. The Magic thing, I get it, why you want to ask. I respect the man, but I can’t say that I’m upset I’m playing this role.

In Season Two, Magic finds himself hurt, and he’s facing professional mortality. From your own sense of your career, the writer’s strike, and other potential labor unrest, can you relate the anxiety of great player feels to that of an actor, wondering if there will be a Season Three of Winning Time?

Very much so. It’s funny, cause it happens all the time where I’m like, Man, what if this doesn’t work out? What if Season Two comes out and nobody likes it? What if the movie I’m shooting isn’t a good movie? All of these things. But at the end of the day, I usually am like, OK, Q, trust yourself, man. Just bet on yourself. If you didn’t think you were going to succeed you wouldn’t have put yourself in this situation. And if I don’t succeed, I know I gave it my all. And: I pivot. [Laughs.]

During filming, what is the percentage of time you spent doing basketball sequences versus dramatic material?

I would say like 60-40 drama to basketball. We shot it in blocks. They blocked it off. They had to switch over the floors too—whether it’s the 76ers or Boston.

In the show, there is much breaking of the fourth wall, with actors talking to the camera, or even just looking at it.

It’s really cool. I love the fact that we do it so much. We have a freedom; we’re encouraged to do it. Sometimes I’ll look at the camera and give a look, or wink. Because if it feels right, do it.

Magic stood out because he was so natural on TV. You are part of a generation that is used to being filmed. Is it radically different filming yourself on your phone than being on a set? Despite the professional trappings, did you still feel pretty natural in front of a camera?

Yeah. You just focus on the task. There are all these cameras and people, but at the end of the day I got to focus on what my character needs in this moment—and not me being nervous about messing up. It just wouldn’t work.

Can you draw on your athletic background—discipline, repetition—and transfer that to acting?

Sports is a cousin to acting. You practice. It’s physical. It’s reps. You have a game or a performance and you have to throw all the practice out and just feel your way through the game. Because once you start thinking your way through it, you start messing up or over-acting.

I know some actors hate looking at their work. Do you watch yourself like an athlete studying film?

QI: Yup, yup.

Do you ever see the takes that aren’t used in the final cut?

I won’t go the monitors on set unless there’s a scene where I’m like, Whoa, I want to see that scene. Because I know that sometimes they might not use that take. But I want to see what that take would have looked like on TV.

Do you see any relation to an ensemble piece like Winning Time and the camaraderie you had playing football?

Yeah, sure. It’s a team process. The editors, for example. I don’t get to see them much unless I go to the editing room and that would just be me going up there to say hi. But they are a big part of the show. Huge. People are doing all these different things to make this great thing. It’s 100 percent a team effort.

So after all your preparation, was the response to Winning Time what you were expecting?

I think it was about the same. It was better than I expected. I kind of felt it was going to be a big thing, but just the positively that’s come—the amount of people that say “critically acclaimed”—that’s just wild to me.

The series is very cinematic. It's almost like a history course in the movies. Then you are working with an actor like John C. Reilly, who was in Boogie Nights—a movie whose stylistic influence can be felt all over Winning Time.

Dude, John is such a beast of an actor. There is so much stuff that doesn’t make the final cut—where you can just see how good he really is. It’s being versatile with your choices, but still being authentic with the intention behind it. That’s tough. To be able to make a different choice as an actor and to do it where you truly believe it, that’s where you’re having fun. It’s a feeling. And he’s really good at that. It’s crazy because he wasn’t supposed to be Jerry Buss at first. And he is the embodiment of that character. It’s just dope to be able to work with him on set. And to know him outside. He came to my mom’s birthday party in Michigan last year. We did a 60th birthday during the summer and he came by, so he’s just a good dude, you know what I mean?

It sounds like a masterclass in acting working with him.

One thing John did—this is why he’s the Hulk—one time I dropped a line, and the line was important to his next line. He incorporated my line into his line and kept the scene moving. That’s how good he is. That’s God-tier talent.

It’s also an improvisational assist. And nobody would know about it unless you’re on set or one of the filmmakers.

The story still got told in the way it’s supposed to. Those are the things I’m exposed to. And I’ll give you another example. We’re shooting a scene in episode five where I’m yelling at John. And he tells me, “Hey, forget the lines, man, just go there.” And that’s when something flipped—or not flipped, but that’s when I felt more control over the words. Stuff was just coming out of my mouth and it wasn’t in the script. That came from John just telling me, "Hey, just go. Forget the script. Say what you’re trying to say."

You Might Also Like