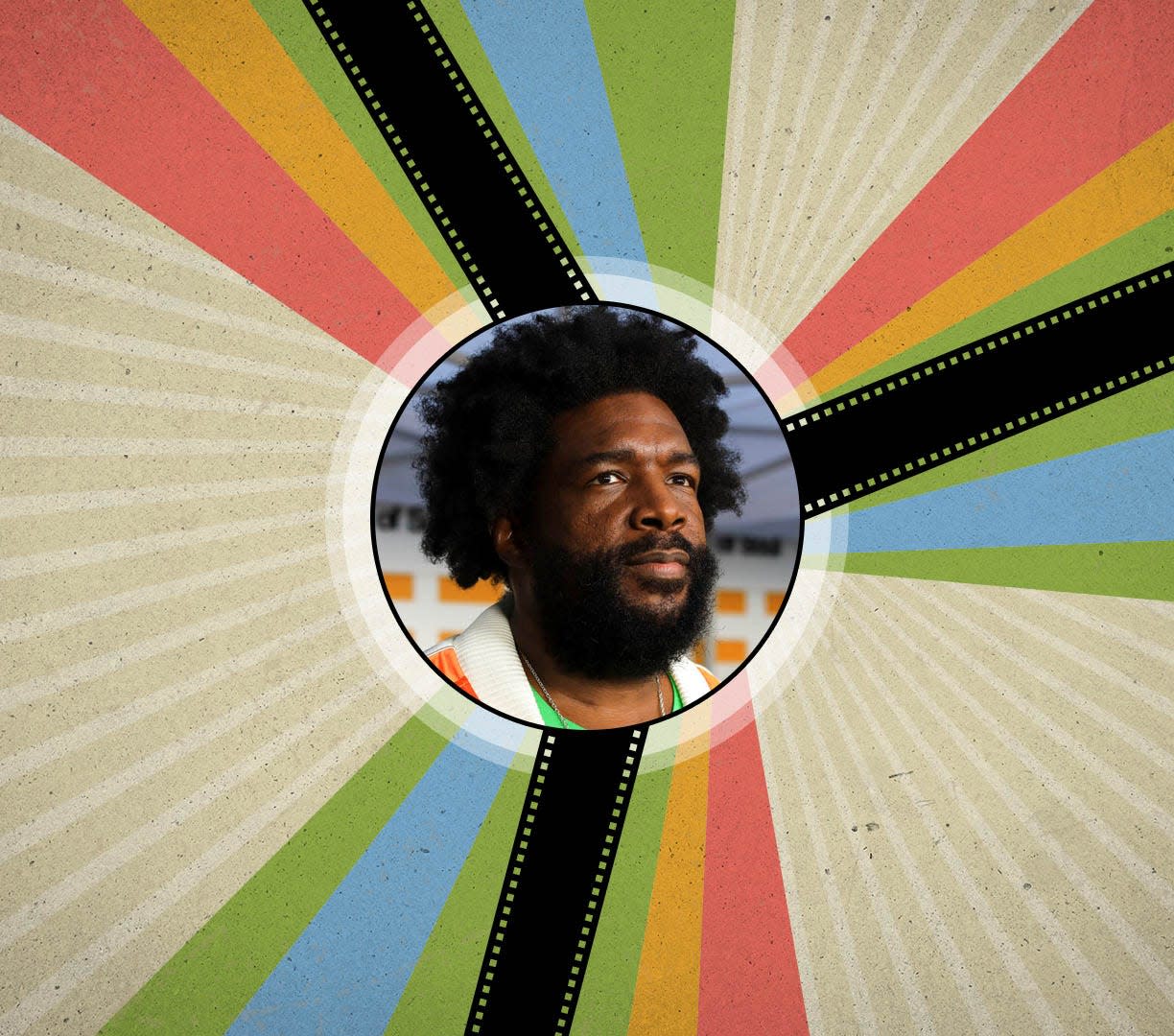

How Questlove turned a forgotten music fest into 2021’s most ‘compelling’ documentary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Questlove was schlepping to work in a nor'easter when he learned he was a Sundance winner.

It was early February, and The Roots frontman had just premiered his exhilarating directorial debut, "Summer of Soul (Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)", at the virtual Sundance Film Festival. The movie, which revisits the long-forgotten 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, picked up the fest's top two documentary honors: the Audience Award and U.S. Grand Jury Prize. But when the announcement was made, Questlove was preoccupied with getting to Midtown Manhattan, where he leads the in-house band at "The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon."

"By the time I got to 30 Rock, there's 10 inches of slush on the ground, it's hailing, it's windy," recalls the musician (real name: Ahmir Thompson). "Tabitha Jackson, who runs the festival, calls and is like, 'You won Sundance!' And I was like, 'Oh, this is like a contest thing? Cool, thank you.' "

"Really, my only concern was, 'Damn, I wore Crocs in the snowstorm. I need some dry socks right now.' "

The best movies we saw at Sundance: 'CODA,' 'Summer of Soul' and more

Boasting 97% positive reviews on aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes, "Summer of Soul" (in theaters and streaming on Hulu Friday) looks back at the Harlem Cultural Festival, which was held over six weekends in 1969, the same summer as Woodstock. But the event, nicknamed "Black Woodstock," has largely been lost to history, despite a combined attendance of 300,000 people – predominantly Black Harlem residents – and an all-star lineup of Black artists including Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, B.B. King and Sly and the Family Stone.

Flash forward to a few years ago, when producers David Dinerstein and Robert Fyvolent unearthed lost footage of the festival shot by the late Hal Tulchin, who tried selling it to TV networks 50 years ago to no avail.

"I think we can all guess as to why that is," producer Joseph Patel says. "There's a reason why Woodstock was well-known and this festival was not, and that says something about this country. Hopefully, this film is one step in helping to rectify that."

Question: What was your reaction when David and Robert told you this footage existed?

Questlove: I was shocked. I just kept asking, "How? It's Sly and Stevie!" Those two names alone merit rolling out the red carpet. You're trying to tell me for 50 years, this was just lying dormant in someone's basement? Suddenly, I became concerned: I'm a first-time driver. Why am I driving this 18-wheeler across the country? I just got my permit. I had doubts I could tell this story and they convinced me, "Dude, you've written books. You teach class. You have a podcast. You know how to tell a story." It took me about three months to really accept this challenge, and once I got started, there was no turning back.

'The Sparks Brothers': Edgar Wright talks music doc and why he's 'a frustrated band member'

Q: What was the process like of editing it together?

Questlove: I had to live with 40 hours of footage for five months on constant loop in my house. I never turned the television off once. I come home, TV still running. Go to bed, TV still running. Every room in my house, monitors everywhere. Even on my phone, traveling – I just absorbed this for five months. When I had 30 moments that I felt were goosebump "wow" moments, that's the foundation I built the movie on. The first draft was 3 hours and 25 minutes, so we spent a good year getting rid of 90 minutes, which was one of the hardest things ever.

Q: You chose not to highlight Stevie Wonder's hits, but instead show him as a 19-year-old at a career crossroads. Why was that?

Questlove: It's so funny you mention that because both my aunt and my mom looked at me and said, "Only you would choose 'Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day' as the song in the show. He's doing 'I Was Made to Love Her' and 'My Cherie Amour' and all these other songs, why'd you choose that?" I chose it because of his entire set – aside from the drum solo – that was the most compelling moment where you saw him going into a zone that wasn't professional Motown. You see these seeds of future Stevie Wonder come to life.

Q: How did you feel watching Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples sing "Take My Hand, Precious Lord" for the first time? Because I, like many critics, was floored.

Questlove: Right? So here's the thing: When we did the first cut, that Mahalia / Mavis moment was my ending. (The producers said), "It's great, it's the perfect Hollywood ending." And I was like, "Oh, man, that's like you saying, 'This is interesting.' " So instantly, I do what I do with Roots albums: I keep what is necessary and start over again. I realized to challenge myself, we should make that summit meeting not our ending, but put it as the climax. Because now I'm gonna be forced to come up with an even stronger ending that has to match this moment.

Luckily for us, in Nina Simone, we had somebody that just really, really hammered it home her way. Nina Simone was more of an exclamation point, as opposed to a period. It would have been a kumbaya Hollywood ending had I ended it that way with Mavis and Mahalia, but as a climax, it hits you even deeper.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Q: This film is ultimately about how Black history and culture are erased. Beyond just getting to enjoy all these incredible performances, what do you hope audiences learn or take away?

Questlove: I knew instantly that people my parents and my grandparents age were going to gravitate because they lived through that period. Cats my age had trickled-down information from their parents and hip-hop also helped. You might not know Gladys Knight & The Pips directly from their catalog, but you know those samples.

When we started inching toward the end of 2019 and the top of the pandemic, then I realized, "Oh, now we just opened the doors for Gen Z and millennials." Because even though they're not connected to these artists in a way they're connected to Drake or Megan Thee Stallion, they're going to see (parallels between the '60s and now). We always wind up repeating history, and that happens when you discard it or throw it away. So I think the obvious thing is that what we're living through right now is what happened 50 years ago, and how can we stop it? That's what I really want people to get out of this.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 'Summer of Soul' unearths new Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone performances