How the Publishing World Is Muscling In on Hollywood Deals: For Authors, “The Future Is Multihyphenate”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This June, when the Netflix film Spiderhead hits the streamer, something revolutionary will happen — but blink and you’ll miss it. Before the opening scene of the dystopian drama starring Miles Teller, Chris Hemsworth and Jurnee Smollett, the New Yorker logo will appear on the screen. The script is an adaptation of a 2010 George Saunders short story, published in the magazine under the title “Escape From Spiderhead.” The film was produced by Condé Nast Entertainment (CNE), one of the first major projects under the group’s new president, studio veteran Agnes Chu.

Spiderhead’s path to the screen is part of a new push to rethink the traditional page-to-screen pipeline — which insiders on both ends of the dealmaking equation say is meant to bolster the authors behind the IP Hollywood covets.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Tom Cruise, 'Top Gun: Maverick' and the Uneasy Echoes of Hollywood Past

How the Current Wave of More Inclusive Leadership Is Changing Newsrooms

For decades, book agents would identify the upcoming titles on their publishing slates best fit for film or television, pitch to counterparts at the major Hollywood agencies, and then sit back as producers and film creatives picked the most promising projects and shepherded them the rest of way. “There had to be a better way to get authors a place at the table,” says Todd Shuster, co-CEO of Aevitas Creative. The lit agency has developed several pipelines to secure more autonomy for authors and their representation, including a first-look deal with Anonymous Content that allows literary agents to serve as producers. One fruit of this union was the 2020 Netflix movie The Midnight Sky, adapted from the novel Good Morning, Midnight by Aevitas literary agency client Lily Brooks-Dalton. Directed by and starring George Clooney, the film reached Netflix’s No. 1 spot in 77 countries, giving Shuster, who has a producer credit, the confidence that the model could work.

With fewer layers between the creators of the written stories in question and those calling the shots on the film or TV version, it’s easier to preserve authenticity — something that today’s increasingly devout literary fan bases require. And by serving as producers, agents are able to defend the authors’ interest. Such deals allow them, for instance, to advocate for the authors themselves to work in a screenwriting capacity, something that’s becoming increasingly common: Sally Rooney worked alongside former Succession scribe Alice Birch to create Normal People; Lisa Taddeo is in the writers room for Showtime’s adaptation of her blockbuster Three Women; and Brandon Taylor penned the script based on his debut novel, Real Life, to which Kid Cudi is attached to star and produce.

There are strong economic and financial upsides for the publishing world. For agents, the possibility of getting in on screen development deals provides extra incentive to spend months or years revising proposals and manuscripts with their clients to make them ready to pitch to book editors. Authors, for their part, find that decreasing book royalties and often-paltry paychecks have forced them to look beyond books to make a decent living.

“The future is multihyphenate,” says Liz Parker, head of Verve Talent Agency’s publishing arm, which recently opened a New York office. The department sources books with an eye for adaptation and strives to help authors become full-fledged creators. Among other projects, Verve represents author Akwaeke Emezi for the adaptations of their novels You Made a Fool of Death With Your Beauty — developed by Michael B. Jordan’s Outlier Society — and Freshwater, under development at FX. Emezi is an executive producer on the former show and a producer and writer on the latter.

Meanwhile, publishers like Condé Nast and Vox Media, which owns New York magazine (from which articles have been adapted for projects like Netflix’s Inventing Anna), are building out in-house production arms in hopes of bringing revenue into the beleaguered magazine industry, and maybe even convert viewers into subscribers. CNE was created as part of the pivot-to-video strategy that many traditional magazines hoped would offset lagging newsstand sales and disappearing advertising dollars, and has since expanded into more ambitious Hollywood projects.

Chu, CNE’s president, was hired from Disney+ with a mandate to be as proactive as possible with the IP from the magazine group’s legacy brands like Vanity Fair, GQ, Vogue and The New Yorker. Her (largely female) team — including Chu’s second-in-command, Helen Estabrook, whose producing credits include Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash and Jason Reitman’s Young Adult — scours lineups for big- and small-screen potential, often bringing stories to the development marketplace before they’re published. Upcoming CNE projects include a documentary based on Wired’s “A People’s History of Black Twitter,” by Jason Parham, and an unscripted adaptation of Vanity Fair’s investigation into Hillsong pastor Carl Lentz’s extramarital affairs, by Alex French and Dan Adler. A more prominent seat at the development table gives CNE more negotiating power to score big wins like the Spiderhead title card, which Chu hopes will strengthen brand identities for the magazines.

Yet the magazine writer’s place in such option deals remains murky, because staff and freelance contracts often give publishers first dibs to option the work in their pages on terms advantageous to the publication. The next step? Getting magazine writers the same kind of autonomy book agents have carved out for novelists and nonfiction authors. CNE has a few yet-to-be-announced films in the works for which they’re helping authors get involved in the screenplay. “We’re showing writers that we have their backs, and that we’re not just brokering the rights,” Chu says. “We’re actually adding creative value.”

Another crucial element of this value-add is the way it can uplift creators of IP who have historically been underpaid or undersupported. Giving writers more creative control and financial rewards over the entire life of a story preserves the integrity of works that are often based on lived experiences. “We’re in an age where there’s a lot more sensitivity to authorial prerogative,” says Aevitas’ Shuster.

To be sure, everyone THR spoke with feels confident that the traditional page-to-screen pipeline will remain the norm. But there are now ever more opportunities for scribes to claim a share of Hollywood glamour, and — crucially — to reach a wider audience. “It’s an attention economy right now,” says Chu. “Everyone is competing for people’s time.”

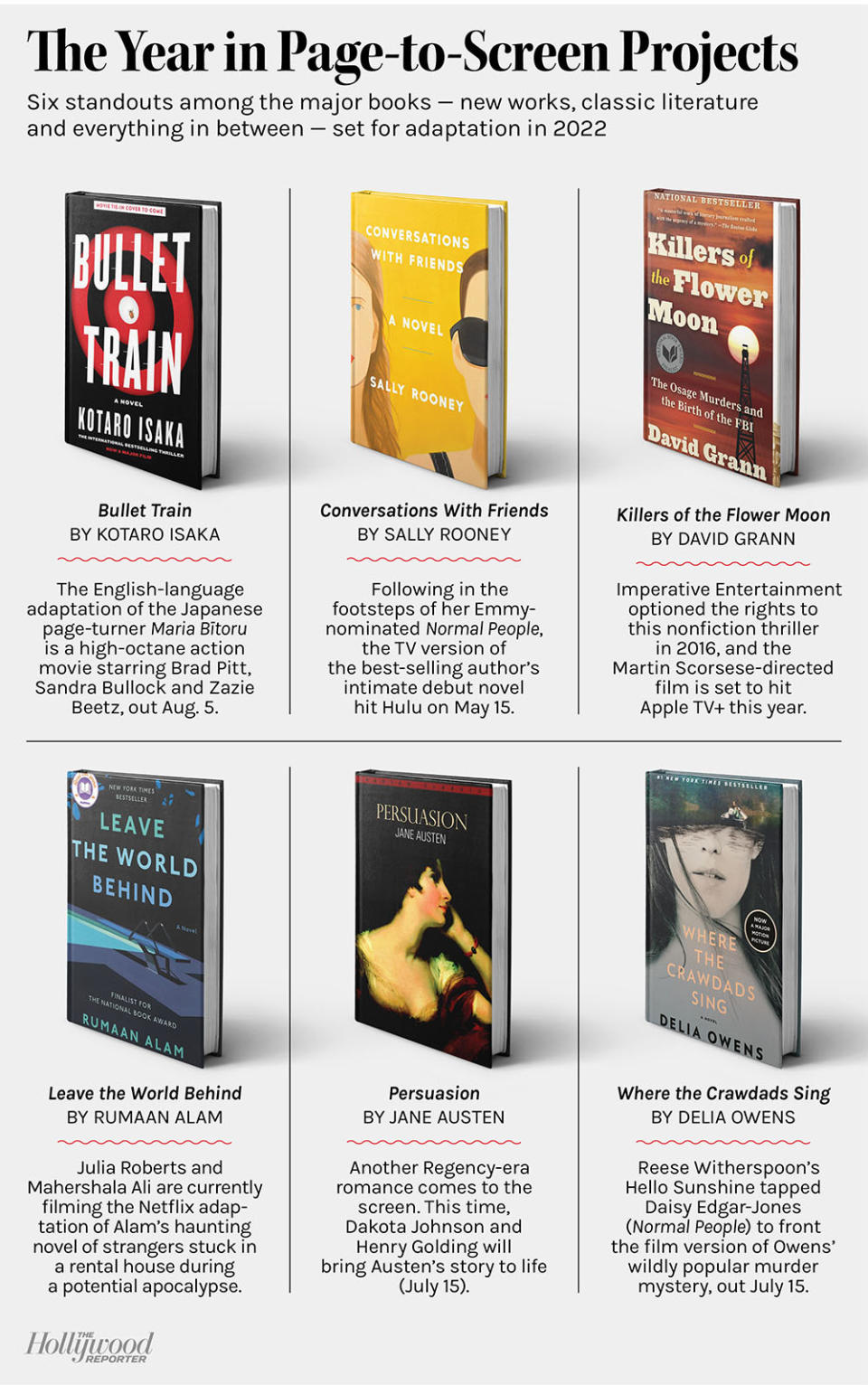

Bullet: Courtesy of Abrams Books. Conversations: Courtesy of Hogarth. Killers, Persuasion, Where: Courtesy of Penguin Random House. Leave: Courtesy of HarperCollins.

This story first appeared in the May 25 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.