The Pre-Dawn, Gear-Grinding Realities Behind ‘Farm to Table’

The primary method by which restaurants receive product from independent farms is directly via door-to-door delivery from the farmer themselves or a delivery driver the farm employs, or by visiting the farms’ stands at local farmers’ markets.

During the seasons that permit it, Tayler and/or Thomas visit the Green City Market—a sprawling Brigadoon of all things edible—in Mary Bartelme Park in the city’s West Loop on Wednesdays and Saturdays. There they replenish their inventory, especially from farms that don’t deliver to them, including Smits Farms, from which they purchase the thyme and rosemary for our dish. But most of the restaurant’s proteins (fish, poultry, and meats) and produce are delivered directly to them by farms located within a roughly 120-mile radius of Chicago. (Dry goods mostly arrive in mammoth trucks emblazoned with the logos of national gourmet suppliers like Chefs’ Warehouse and Rare Tea Cellar.)

For a sense of what deliveries entail, I meet Marc Hoffmeister at Nichols Farm’s cleaning and packing facility at 3:30 a.m., electric light beaming in Spielbergian shafts from the structure’s handful of loading docks. The sky above may be dark as squid ink, but here the business day is well underway: Clusters of workers in T-shirts and work pants swarm each dock, and if you’re still shaking the sand out of your cranium as you navigate from one end of the hangar-like structure to the other, you run the risk of getting pancaked by a forklift. Everyone seems entirely too energized and enthused for this hour of the morning. Take, for instance, the man who speeds past me in a forklift.

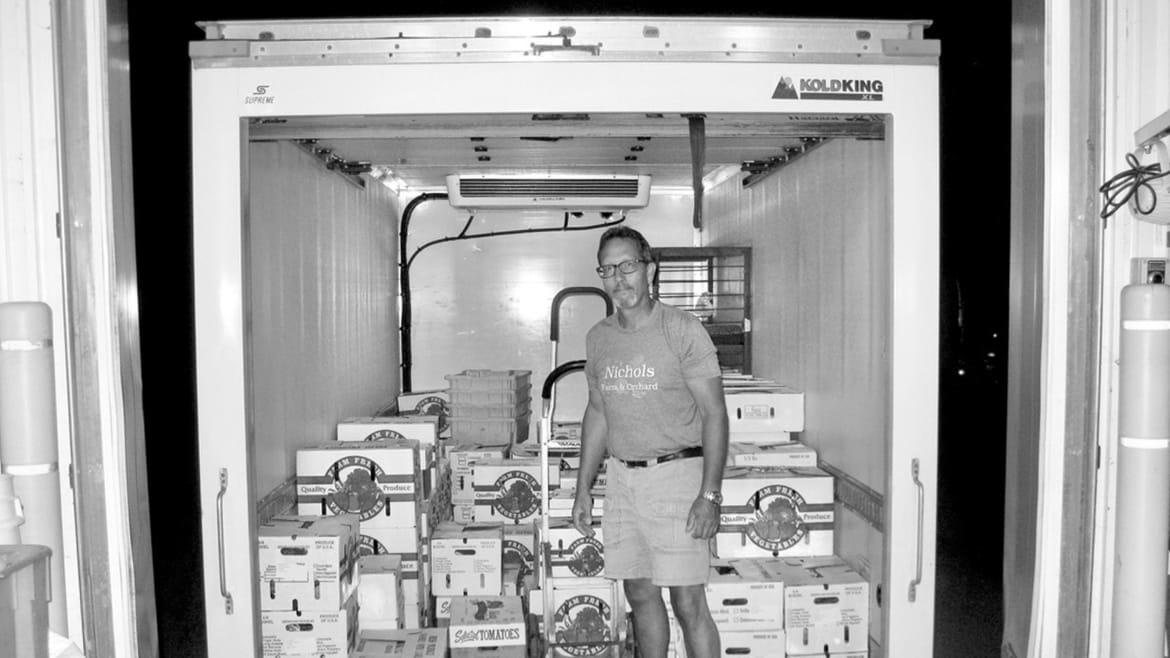

Marc Hoffmeister at the outset of his day, around 3 a.m.

“Mr. Fried-man!” he hollers. It’s Steve Freeman, that Nichols team member I met at the Green City Market.

“Mr. Free-man!” I manage back, smiling through a yawn.

This being August, the perfume of peaches owns the air. Trucks bound for farmers’ markets require a team to pack them; those being cargoed for restaurant deliveries are managed by lone specialists like Marc Hoffmeister, who’s already there, at the backmost dock, organizing an array of boxes emblazoned with a generic farm fresh vegetable logo, most with the name of their destination restaurant scribbled in black Sharpie in a corner of the fold-down top.

When Wolfgang Puck’s Spago Was the Epicenter of L.A.’s Social Scene

Marc is fit and spry, with a tight core and muscular legs that belie his 60 years, as does the enviable black of his hair and goatee. His khaki shorts, forest-green Nichols T-shirt, and affability lend him the air of your favorite camp counselor. But don’t be fooled. Yes, Marc is personable, and funny. But he also, to borrow a line from the Taken movies, possesses a very particular set of skills. He is, in fact, relative to most other drivers what a Navy SEAL is to a high school crossing guard.

He’s also, alas, human, and subject to corporeal wear and tear. He’s come to believe that back-support belts only serve to weaken one’s spine and abdominal muscles, so doesn’t use one, though a battered black lumbar support wedge rests on his driver’s seat. He fends off muscle tweaks with a daily prework hot shower, stretching routine, deep-knee bends, coffee, and breakfast. He arrives loose, caffeinated, fueled up, and ready to go.

During the COVID pandemic, Nichols developed a CSA program, selling and delivering boxes weekly to homes or hub-locations from which orders are picked up by nearby customers. Boxes bound for those destinations bear small labels imprinted with individual customers’ names, a reassuring glimmer of organization among a seemingly haphazard spray of boxes on the cement floor.

“I might look like I’m all over the place,” Marc tells me, gesturing at the mess. “But there’s a system.”

And here’s the first of Marc’s powers: He performs most of his work without the aid of computerized gadgets save for his mobile phone—surprising and impressive in the digital age. Armed only with his eyes and a ballpoint pen, he crosschecks the boxes against a stack of invoices fastened to his clipboard, ensuring that his freight is complete. Then he piles boxes on his “two-wheeler” (that’s hand truck to you and me) and loads them into his truck—a 2018 Chevrolet Express 4500 with a 16-foot box (shorthand for the 16-foot-long cargo area; this one is eight feet wide) and a Thermo King refrigeration unit (reefer for short). The day’s last deliveries go in first, that is, at the back. Also at the back, on the passenger side, stands a metal utility rack on which Marc places flats of delicate greens and inverted box tops that he’s repurposed as trays for cherry tomatoes.

Another employee—a wisp of a woman I’d put around 60 with graying blond hair and a hitch in her step—stops to politely ask me what I’m doing there. I tell her about the book project. She nods, smiles kindly, gestures around at the co-workers buzzing about: “All the people nobody sees.”

This is still a transitional time in the COVID era so Marc and I have a chat about our mask policy for the day. “I’m Pfizered up,” he offers, meaning vaccinated. I tell him that I am, too. We agree to keep the windows down and our masks in our pockets so they can be strapped on at stops along his route where it’s required by management, or the staff wear them voluntarily.

By 4:40 a.m. Marc and I are on the road, fueling up at a gargantuan Road Ranger service station on US 20, near Hampshire. Then it’s onto I-90 South, aka the Jane Addams Memorial Tollway, which becomes the Kennedy Expressway on the other side of O’Hare Airport. Hours into Marc’s workday, the highway’s a river of headlights though the sky retains its nocturnal blackness. We pull off in northwest Chicago and cruise into the desolate parking lot of an Eli’s Cheesecake at 5:30 a.m. This is our first stop of the day: a CSA pick-up location for farmers’ market customers. Melons have recently come into season, adding heft to the boxes. Outside a set of glass doors, Marc stacks six boxes, plus one for Eli’s cafe, containing melons, tomatillos, beets, and garlic.

Many of Marc’s colleagues avail themselves of a routing app like Circuit Route Planner or RoadRUNNER Rides: You punch in all of your destinations, and it sequences them logically, then functions as a GPS, essentially reducing the driver to a human liaison between app and vehicle. Marc, a Chicago native, knows the city’s nooks and crannies, traffic patterns and rhythms. And he don’t need no stinkin’ GPS.

“This is all stuff I learned when I was a kid,” he says, imparting the organizing principles of Chicago’s street plan: Madison Street is the “zero” point for north–south; State Street is “zero” for east–west, and so the center of the city’s grid is the intersection of Madison and State and each block moving outward from there equates to 100 address numbers.

Marc’s cultural breakdown is half Assyrian and half German, with a family tree whose roots extend to both the culinary industry and the city of Chicago: His maternal grandfather was a chef at the historic Palmer House Hotel in downtown’s Loop area, and his father-in-law served as a sergeant with the 18th District on the city’s Near North Side. Marc was born and raised on the Far North Side, in East Rogers Park, just inland from Lake Michigan. After high school, he worked for an excavator, and in his twenties partnered with a friend in a remodeling and construction business. He’s been a draft beer restaurant sales rep and was a concrete laborer for the city until budget layoffs ended that after nine years. Next he moved to Crystal Lake, a midsized city about fifty miles northwest of Chicago, where he made his living as a salesman for a medical supply company, but was let go when they pared down their routes. That’s when he set his sights on Nichols, which he knew from the Evanston farmers’ market. He looked up the farm’s address and headed there. Lloyd hired him on the spot.

A little past first light we ease up to a house on the northwest side of the city along what Marc calls an “alley”—a bank of row houses opposite corresponding storage garages across the street. There he leaves ten CSA boxes plus one for the host. That’s the arrangement: Residents who volunteer their homes as pick-up locations receive a freebie for their trouble. (The drop-off locations double as pick-up locations for used boxes; yesterday Marc rounded up about one hundred.)

Except in extreme circumstances, Marc doesn’t secure signatures or snap digital photographs of shipments resting safely on porches as proof of delivery the way, say, Amazon couriers do. “If people steal,” he explains with what’s quickly emerged as a characteristic fusion of wisdom and humor, “they’re looking for a phone, not a box of beets.”

Sunlight bursts upon skyscrapers as we continue on our way, and the city rouses around us. Slowly, we’re synching up with the world, or it with us. Commuters wait at bus stops, joggers sweat through their kits in the mid-summer swelter.

Our first restaurant stop is Longman & Eagle, a modern iteration of a historic Chicago inn, complete with whiskey bar downstairs and rooms for rent on the second floor. Something on the invoice sets Marc’s left eyebrow atwitter. His Luddite ways have screwed him—he’s short one box of corn. There should be three for this restaurant, in addition to the squash and heirloom tomatoes packed into other boxes.

“There’s always a monkey wrench,” he says, shaking his head. You or I might panic at a missing box of corn, but Marc has seen and done it all before. He decides to loan himself a box from another order, with hopes of replenishing it by swinging by the Nichols tent at the Green City Market. (The other option would have been to short another customer one box and have it dropped off the next day.)

One of the cooks, dressed head to toe in black, is already in the kitchen and appears in the doorway.

“I haven’t seen you in a while,” says Marc, a natural and earnest kibitzer. “What time did you get here?”

“Five.”

Back in the truck, the driver’s seat morphs into a command center. Marc calls around to various colleagues, finally reaching Nick Nichols on the farm in Marengo, and asks him to let Steve Freeman, who’s honchoing the farm’s Green City Market encampment today, know he’ll be swinging by to take a box from him.

“That’s a good pivot when you can do it,” he says, mic-dropping the clipboard into the black plastic chasm between driver and passenger seat.

Looking back later, the morning to this point will prove to have been both harbinger and microcosm of the hours ahead: Marc is personable and adaptable, and both qualities are essential to his work, the way a poker face and bullshit detector are to investigative federal agents. In the suburbs or country, parking and unloading a truck pose no challenge to mind or heart rate. Major American cities, on the other hand, present as veritable obstacle courses: traffic, a scarcity of available spaces that are scaled or zoned for trucks, and the threat of a parking enforcement officer lurking around every corner. (Practically speaking, parking tickets are a cost of doing business, but it’s a point of pride not to incur one. Marc can’t remember the last time he was ticketed, thanks in part to compassionate cops who accepted his claim that “I’m not parking. I’m making a delivery.”)

En route to our next stop, Marc reveals to me that there’s an overriding strategy to the day: The goal is to arrive at Brü, a hipster caffeine parlor on Milwaukee Avenue in Wicker Park, around eight or eight-thirty, a beat ahead of the worst morning traffic. This will in turn enable him to ride off into the sunrise, to Lincoln Park and then to suburbia, confident in the knowledge that he’s equipped some of the best restaurants in Chicago with precious fruits and vegetables for… whatever it is they make in there. Marc and his wife, Jena (pronounced like “Gina”), are not really “out-to-eat people,” as he puts it. They don’t live in the city, she went vegetarian eight months ago, his work schedule isn’t compatible with fine dining, and it’s expensive.

A few quick stops later and as 7 a.m. approaches, we’re cruising east, in the general direction of Lake Michigan. We dock in front of Maple & Ash, a modern steakhouse and seafood restaurant, in a loading zone on Maple Street, around the corner from the delivery entrance.

From Serving Time to Serving Food: EDWINS' Winning Recipe

Maple & Ash’s cooks operate out of two kitchens, one on the third floor and one on the fourth. Accordingly, Marc splits the order and will make two trips; he stacks the two-wheeler up to its handlebars with boxes bearing corn, cherries, sweet-skinned cucumbers, and Tropea onions, and uses his fob to lock the truck. (He has a special affinity for this model because he can keep the reefer running even when the truck is locked.) We walk around the corner to a back alley, up to an unmarked door, and Marc shifts into secret-agent mode: He punches in a long code—five or six digits—from memory and we’re in a shadowy employees-only corridor. A quick elevator ride to the third floor and we’re in a clubby, wood-paneled restaurant space—closed and deserted at this hour—that conjures the Caribbean, prompting a sudden, unfashionably early craving for dark rum and contraband cigars.

Even just unloading a delivery truck is physical work.

“Morning, you guys!” Marc bellows as we roll into the kitchen, a narrow galley where a handful of cooks wearing pandemic-era surgical masks (we’ve put ours on) are already hard at work with the morning’s prep—slicing vegetables, butchering fish and meat, sautéing that which can be sautéed in advance, cooled, and reheated during service.

“I brought you a bunch of great stuff,” Marc continues, tipping the two-wheeler forward, then back, to ease the cargo off. “Great fruits and vegetables for you!”

The team smile and nod.

Back at the elevator, his mask lowered, leaning an elbow on the two-wheeler, Marc picks up with his intermittent running narration. “This elevator, when it’s busy, there’s another one around the corner,” he says. As if I wouldn’t believe him, he gestures me to the other elevator, flanked by two stanchions with a velvet rope suspended between them. “You remove the rope and—boop!— you’re downstairs.”

The elevator’s taking a while to show up, so he shares a little more intel: “If you need a washroom,” he says, indicating a door tucked into a recess along a nearby corridor, “that’s a good one.” Even just unloading a delivery truck is physical work.

We head back outside and around the corner to load the two-wheeler up with deliveries for the fourth floor. In our short time indoors, the sun has climbed higher and vehicles of every shape, size, and color now clutter up the street. Marc spots a paving truck near the alley that leads to the delivery entrance, and picks up his pace so he can get in and out before the truck backs around the corner onto Maple Street, where it might box him in. This isn’t paranoia: “One time,” he tells me, “a Sysco truck blocked the alley.” A pause for dramatic effect, then a shrug: “They [the building’s powers that be] let me in the front.”

In these minutes, more truths have emerged: Big-city high-rises constitute universes unto themselves, with their own fiefdoms, elevator banks of varying efficiency, security protocols, amenities (if applicable), and workarounds. The morning gradually assumes a behind-enemy-lines tension as Chicagoans clog streets, fill elevators, and generally get in the way. Marc is on a mission, and superintendents, security guards, commuters, and traffic cops inadvertently conspire to thwart him. And so, every stop on his route is a problem to solve, a solution to be finagled, a test of his improvisational skills and the limits (if there are any) of his sprezzatura: where to stash the truck, which point of entry to each destination offers the least resistance, what to do if nobody’s on hand to receive an order. (At some point in the day, maybe owing to sleep deprivation, I fantasize pitching a reality-show concept: Delivery Wars!)

Challenges are baked into some venues, and Marc recounts them with gusto. Like, for example, the day prior, Steve Freeman had to make three trips to the sixty-seventh floor of the Metropolitan Club. I’ve been helping Marc a little, loading the two-wheeler or carrying flats of delicate cherry tomatoes. And so, I can commiserate.

“Man,” I say, shaking my head solemnly.

Turns out, that’s nothing. As we breeze past the Art Institute of Chicago, Marc bemoans its impenetrability; he has yet to identify a lever to pull, a button to push, a loophole to exploit, a gatekeeper to flip, to make it more delivery-friendly— you have to park three blocks away. One time, to transport an ungodly amount of produce for a wedding, he had to do that and make ten trips to and from the truck. Trust him: You don’t even want to know how much time that ate up.

“Jesus,” I moan.

By seven-fifteen, we’re cruising State Street, that grand, expansive, Frank Sinatra–lauded thoroughfare, its signature American magnificence arrayed before us, and minutes later we arrive in front of the Chicago Athletic Association, a nineteenth-century skyscraper that’s been reinvented as a hotel with seven food and beverage options within its confines. It’s a mammoth order: nine boxes bearing melons, French beans, green beans, heirloom tomatoes, cucumbers, Tropea onions, a full case of eggplant, and a flat of cherry tomatoes. We get off easy today, having to make only two trips with the two-wheeler.

A few more quick stops and suddenly we’re trudging along a gloomy, otherworldly mashup of an alley, a tunnel, and a parking garage that, to my eye, extends endlessly ahead of us. Marc explains that we are on “Lower Michigan,” an alternate thoroughfare that runs under Michigan Avenue for several blocks to the north and south of the Chicago River, and manifests as a double-decker bridge across the river. “This is like the bowels of the earth,” he laughs over the truck’s rumble. “You can take it from one end of downtown to another, but I got friends who won’t ever come down here.”

At 8 a.m., we pull up outside the Italian gourmet market Eataly, home to multiple restaurant concepts including a market osteria, a pizza and pasta concern, and a Lavazza caffè, as well as cooking classes. Today, Marc’s delivering melons, Sungold tomatoes, and cucumbers to the osteria, and forty pounds of heirloom tomatoes to La Pizza & La Pasta.

At our next stop, we find ourselves underground again, this time beneath the Reid Murdoch Building, a landmarked redbrick structure with a clock tower at its center, that’s home to the headquarters of Encyclopedia Britannica and also to River Roast, a modern American tavern-style restaurant. Suddenly, we’re confronted with two pairs of loading docks separated by a narrow dead-end service lane. It’s dark and grimy, and massive trucks jockey for position, gears grinding, wheels shrieking.

Even Marc evinces a rare look of consternation. He harbors no love for these tight quarters and the potential for being boxed in by a colleague unmindful of the social contract. A truck that’s idling in our path kindly backs up to enable Marc to back into his desired dock, replenishing his faith in his fellow drivers.

We carry four cases of corn and a flat of cherry tomatoes up a narrow, black steel stepway, corroded in places, and arrive at the delivery door to River Roast. Marc presses the service bell several times, but there’s no answer. This never used to happen, he tells me, theorizing there’s no one available to answer the bell due to the staffing shortage that’s broken out during COVID.

He stacks the boxes on the landing, creates a makeshift platform by stacking a few milk crates that have been conveniently left there, then gingerly places the flats of cherry tomatoes on top—offering as much care and protection as he can as he leaves these delicate little tomatoes to the mercy of whatever may lurk down here.

“There’s no other option,” Marc says with a fatalistic shrug. He calls Nick Nichols to let him know the situation and head off any possible complaint from the restaurant.

After a few hours of observation, I’m in awe of Marc’s capabilities. And so it makes me a little sad when he shares that some of his friends tell him he’s doing grunt work.

“I like what I do,” he insists. “I like the people I work with. I like the customers. It’s fulfilling to me. It’s a workout. I enjoy it.”

We emerge into daylight and the stress gradually falls away. After a quick stop at avec River North, around 8:45 a.m., we head to a mystery stop, a new one on the route, about which Marc has been musing all morning. He’s been calling it “Bain,” evoking the unintelligible Tom Hardy villain in the third Christopher Nolan Dark Knight movie. When I see the name scribbled in Sharpie on the box, I learn it’s actually BIÂN (pronounced bee-YAHN, an approximation of “beyond”).

In the Small World Department, it’s my friend Kevin Boehm’s elegant, exclusive urban retreat, mingling elements of a health club, spa, medical center, and restaurant. The address is 600 West Chicago Avenue, which sounds straightforward, but this is virgin territory for Marc, so he hasn’t yet decoded the best place to park, the best entrance, which doorman or security guard he can press into his service. Plus, occupying a corner location, its main entrance is unclear.

And so we turn onto North Larrabee Street where a doorman, making exaggerated throwing motions with his arms, directs us to a loading dock way down the road, away from West Chicago Avenue. We start in that direction, but Marc quickly knows it can’t be right, so he makes a turn hoping to get back to West Chicago Avenue, lodging instead in a cul-de-sac.

The quest for the proper entrance is taking entirely too long and we’re hemorrhaging time, but Marc doesn’t betray so much as a whiff of anxiety.

“Something I’ve learned,” he says spinning the steering wheel to execute a three-point turn, “is, one way or another, it’s gonna get off the truck. We don’t come back [to the farm] with anything.”

He finally locates the gold-framed doorway on West Chicago Avenue through which members pass into the great BIÂN. In front there’s a drop-off/pick-up slip intended strictly for valet parking. This isn’t conjecture; a sign eradicates any doubt. But Marc knows this is the best place to park because it’s private property immune to the city’s regulations, and so, unless the uniformed attendant decides to force the issue, there’s no threat of a ticket. Assiduously avoiding eye contact, Marc loads up the two-wheeler, and marches into the building with an urgency that suggests he’s a transplant medic delivering freshly harvested human organs. It works: The attendant clearly recognizes something isn’t kosher but declines to protest.

From here, it’s downhill skiing: We drive the roughly two miles to Wicker Park and the promised land of Brü. We missed our self-imposed target arrival time, but only slightly, pulling up at 9:00 a.m. The street is blessedly free of parked cars and Marc stations the truck right out front. Brü’s a pick-up spot for CSA boxes and Marc makes multiple trips with them on his two-wheeler, disappearing into Brü for minutes at a time—no doubt chatting up the baristas—then returning for the next load, delivering thirty in all.

We’ve been relieved of a massive literal and figurative weight. Five hours after pushing off from the Nichols warehouse, the truck is nearly empty. We treat ourselves to a coffee to celebrate, then head to Green City Market, where Marc bolts from the truck, returning in less than a minute with a box of corn to replenish the one he swapped in at Longman & Eagle.

At 10 a.m. we make a drop at Galit, a Middle Eastern restaurant on North Lincoln Avenue, mere steps from the alley where John Dillinger was shot and killed; periodically during the day, tour groups devoted to the city’s criminal heritage pass by and guides detail the bank felon’s demise through a megaphone. Inside, we meet chef Zach Engel, a young, bearded, and affable guy who gabs it up with Marc.

As big a city as Chicago is, its restaurant ecosystem is intimate: Zach buys copious amounts of za’atar from Smits, the same farm whose thyme and rosemary flavor our dish’s red wine sauce, and is expecting Butternut Sustainable Farm’s Jon Templin, who will also be dropping off a delivery at Wherewithall, shortly after Marc departs. And he just recently visited Slagel to cook a dinner as part of the farm’s guest-chef series held in the event space on the edge of Louis John Slagel’s property.

Our last stop is at 10:15 a.m., at Dear Margaret, where we visit with chef Ryan Brosseau. I leave Marc here. He’ll head back out to Evanston for a few final drop-offs, and then back to Nichols.

Before we say goodbye, I ask this man of clear intelligence and off-the-charts social skills: Could he have been an office guy?

“Definitely not,” Marc reflexively fires back. “It’s not my makeup. I don’t do well sitting still. I never really thought about doing that kind of work. I’m good with this.”

The Dish

And that is just one reason why many of the people encountered in these pages have gravitated to a life centered on restaurants. Sure, some have a passion for food, but just as many are metabolically incompatible with conventional professional careers. They want—need—to come as they are, be in perpetual motion, work with their hands, and have the freedom to chatter the day away. Until, that is, the time comes for them to pull off the seemingly impossible and, like a Chicago Bulls player circumventing the defense to make an eye-popping dunk, they are in their element, and their talent is plain for all to see.

Excerpted from the book THE DISH: The Lives and Labor Behind One Plate of Food by Andrew Friedman. Copyright © 2023 by Andrew Friedman. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.