Potential Senate fight looms over judicial nominee who helped craft Trump immigration policy

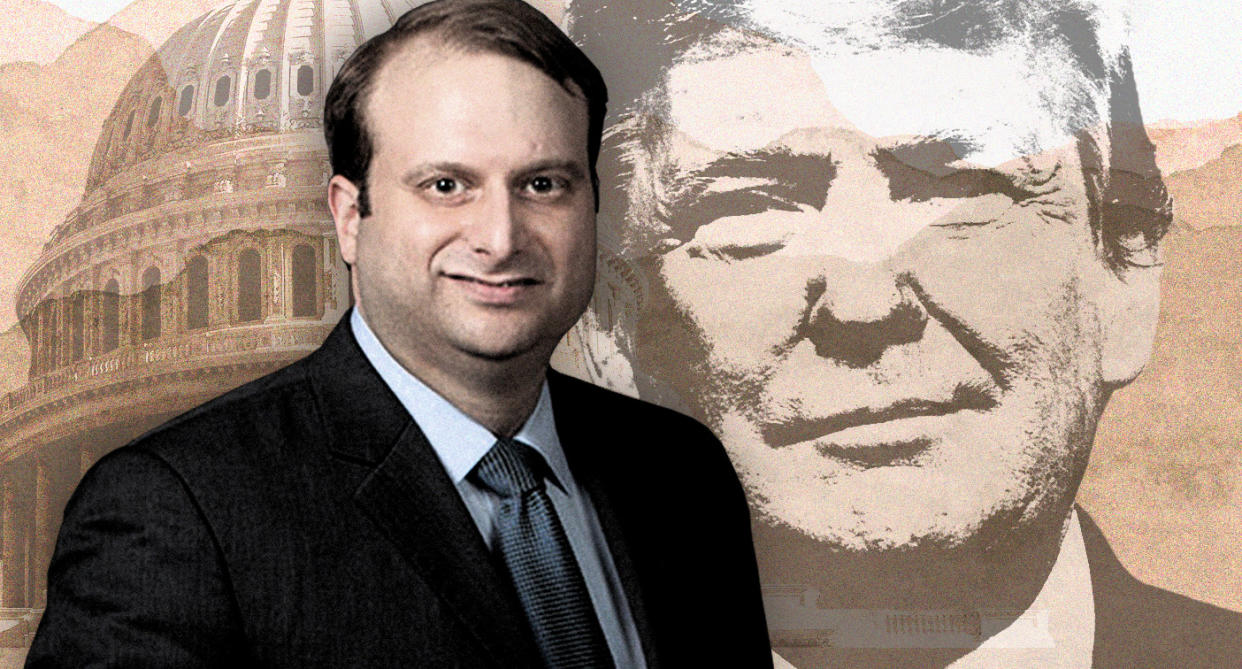

WASHINGTON — Almost exactly a year after the Supreme Court nomination of Brett Kavanaugh turned into a furious fight over judicial temperament, sexual misconduct allegations and political decorum, the Trump administration is facing what could be the 2019 version of the Battle of the Bench: the nomination of Steven J. Menashi for the influential Second U.S. Court of Appeals.

A deft and ambitious White House lawyer admired by Washington’s conservative elites, Menashi was nominated in August. Since then, progressives have pounced on his writings to paint him as a right-wing ideologue who does not belong on the federal bench. And his work as a top lawyer for the Department of Education has some worried that he could perpetuate some of the most controversial policies of Secretary Betsy DeVos, including more stringent standards for reporting sexual assault and tougher rules regarding financial aid.

“Steve Menashi would be Betsy DeVos in a robe,” says Lena Zwarensteyn, who directs judicial branch efforts at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a progressive advocacy group. “He is undeserving and unqualified for a lifetime position on the Second Circuit.” That is almost certain to be a major line of attack deployed by Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee, who will try to tether Menashi to DeVos, who is among the most controversial of Trump’s Cabinet members.

Democrats will just as certainly question Menashi on his work as a White House lawyer, where he has been involved in crafting the Trump administration’s immigration policy.

“It is going to be a tough fight,” acknowledged Mike Davis, a veteran Republican operative who recently founded the Article III Project, an advocacy group that helps install conservative judges. He vowed that his group and its allies on the right would “fight to confirm Menashi, a highly qualified nominee who is being unfairly smeared by the left.”

Progressives say their hands are clean, and that they’ve done nothing but underscore Menashi’s own words, in particular his prolific contributions to conservative media outlets, for which he has written since his days as a college activist two decades ago.

In those writings, Menashi routinely expressed opinions that, today, would make many Republicans uncomfortable. As a wealthy student at an elite college, he once called recipients of financial aid “grasshoppers.” In another article, he praised the “noble aims” of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. And in a law review essay, he criticized “ethnically heterogeneous societies,” leading to accusations that he was a white nationalist — a claim his proponents say is outrageous.

Menashi’s hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee is expected to take place on Wednesday. After that, the nomination will proceed to the full Senate, which is narrowly controlled by the Republican Party. Both parties are already preparing to lean heavily on the half-dozen or so senators who could decide Menashi’s fate. Among them are Republicans Susan Collins of Maine, who was crucial to Kavanaugh’s narrow confirmation, and Tim Scott of South Carolina, whose reluctance sank the nominations of two other judges with right-wing views. Some conservatives think Scott will be the decisive vote, leaving the GOP’s sole African-American U.S. senator to decide the fate of a nominee with controversial views on race.

Should Menashi win confirmation, the 40-year-old appellate lawyer will have a lifetime appointment to a New York City-based circuit court that has produced three Supreme Court justices: John Marshall Harlan, Thurgood Marshall and Sonia Sotomayor.

President Trump has two Supreme Court justices of his own in Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch. But he has had an even greater impact on lower courts, where the overwhelming majority of cases are ultimately decided. According to the Heritage Foundation, a conservative organization that has helped the Trump administration with judicial nominations, Trump has successfully nominated 144 lower-court judges, making his the most aggressive reshaping of the judiciary branch in decades.

Menashi was nominated in late August, when few Americans were paying attention to judicial appointments. And those who were following court issues probably focused on reports about the health of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who revealed she had yet again undergone treatment for cancer.

That has allowed Menashi to escape the kind of public outcry that met last year’s nomination of Neomi Rao, another young, conservative jurist with impressive professional credentials. Menashi and Rao could both be nominated for the Supreme Court one day.

“We’re not making this nearly as hard for them as we could,” lamented Brian Fallon, a former Hillary Clinton campaign spokesman who now runs Demand Justice, a progressive advocacy group. “Walking the plank for this guy should be a very hard political exercise,” he said, citing Republican senators like Cory Gardner of Colorado and Martha McSally of Arizona, both of whom will be running for reelection next year.

Administration officials are conducting efforts of their own, with help from outside groups like the Article III Project and the Judicial Crisis Network, whose chief counsel, Carrie Severino, was among Kavanaugh’s most forceful defenders.

Some conservatives wonder why defenses of Menashi have been more muted, considering the importance and prestige of the Second Circuit. They charge that White House counsel Pat Cipollone, and his deputy in charge of nominations, Kate Todd, did not do enough to prepare for the withering criticism they had to expect from progressives, who are eager to stop Trump’s remaking of the judicial branch in his own image.

The White House would not comment for this story on the record. Matt Lloyd, a Department of Justice spokesperson, told Yahoo News that the office of legal policy “works with judicial nominees throughout the confirmation process. Our work with Steve Menashi has been consistent with that of all other nominees.”

Much like Kavanaugh, Menashi is a cultural touchstone even more than a judicial nominee. Unlike Kavanaugh, he has never been accused of sexual impropriety. Nor, when pressed on his views, is he likely to launch into a Kavanaugh-like tirade about liking beer.

Menashi, however, may suffer from his own shortcomings. One Capitol Hill insider involved in Republican nomination efforts, including that of Kavanaugh, described Menashi as cold and arrogant. He worried that Menashi’s personality alone could hamper him in meeting with senators like Scott.

Menashi is, like Kavanaugh, a product of the Eastern establishment. The son of David K. Menashi, chief executive of the Arizona Beverage Company, he grew up in Scarsdale, the wealthy suburb of New York City. Menashi then attended Dartmouth College, where he wrote for the Dartmouth Review, the routinely controversial conservative publication that minted pro-Trump personalities like Dinesh D’Souza and Laura Ingraham during the 1980s.

It was at the Review that Menashi developed his talents as a flamethrower on behalf of the right’s most sacred causes. In one article, he derided “campus gynocentrists” who were protesting campus sexual assault. In another, he appeared to compare affirmative action to the anti-Semitic laws instituted by Adolf Hitler.

That is precisely the kind of view that could offend Scott, who voted against Trump nominees Ryan Bounds and Thomas A. Farr out of a concern about their views on race.

(Disclosure: I worked with Menashi on the Dartmouth Review. A list of publications he submitted to the Senate Judiciary Committee includes an article we co-authored about campus protests. We have not spoken since at least 2000.)

Menashi continued to write after graduating from law school at Stanford. He was on the editorial board of the New York Sun, a now defunct conservative daily. Later, he founded a blog called the American Scene with Ross Douthat, the future New York Times columnist. After leaving the Sun in 2005, he worked briefly for the Pentagon and later clerked for Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., one of the high court’s most reliable conservatives.

He kept publishing throughout this time, leaving behind an unusually long written record of sharply worded opinions on a variety of matters, from crime in New York City to the Iran nuclear deal. That will make it difficult for Menashi to claim, as Rao did, that his writings represented youthful views he has left behind.

Progressive groups have eagerly combed through Menashi’s writings in recent weeks. The fruits of their labor include an article in which Menashi describes Roe v. Wade as protecting “radical abortion rights” and criticizes family and medical leave as “private comforts.”

Menashi’s sharply worded opinions offer an easy target for his opponents. His 2010 law review article on Israel, “Ethnonationalism and Liberal Democracy,” became the subject of an extended segment on Rachel Maddow’s primetime MSNBC show. Reading from the article, Maddow said it was a “highbrow argument for racial purity.”

Menashi’s supporters were furious because Maddow neglected to mention that Menashi, who is Jewish, was talking about Israel, not the United States, and was attempting to make an argument about democracy and demography. Some even accused her of anti-Semitism. But they were also upset that the White House did not marshal a defense of Menashi to rally Trump’s base.

One person close to the White House thought that Maddow had overplayed her hand, and that if Democrats try to paint Menashi as a white nationalist during his Senate hearing, the effort will only backfire. This person, who knows Menashi personally and is familiar with his professional record and writings, called the nominee an “incredibly bright and thoughtful individual.”

Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee were reluctant to discuss strategy, but challenging Menashi on his writings is sure to figure in their approach. They will also argue that his work for the Trump administration has allowed him to put his stated beliefs into practice.

They are, for example, also certain to bring up Menashi’s work as the acting counsel for Betsy DeVos. Menashi worked for DeVos in 2017 and 2018, for part of that time serving as the acting general counsel, meaning that he was the top lawyer in the department.

Menashi’s calendar entries from that time, which were obtained by the progressive group American Oversight, show that he primarily worked on issues that were important to DeVos and the broader conservative movement, like protecting the rights of Christians on college campuses and combating the purported evils of political correctness. Those calendars show that Menashi had 37 meetings between June 2017 and May 2018 pertaining to Title IX, the federal statute on gender discrimination.

Several months after that, the Department of Education adopted measures that could have the effect of making it more difficult to report sexual assault.

“It’s hard to get a straight answer from the Trump administration,” American Oversight executive director Austin Evers told Yahoo News, “but calendars give us a window into a government official’s real priorities. Steven Menashi’s calendar shows a strong focus on advancing Secretary DeVos’s right-wing social agenda, from rolling back gender discrimination protections to promoting religiously affiliated schools.”

The White House would not make Menashi available for an interview.

Menashi moved in September 2018 from the Education Department to the White House counsel’s office, where he presently works. During that time, he was part of Stephen Miller’s working group on immigration, which sought to implement hard-line policies, including the much-criticized practice of separating parents and children during border apprehensions. Menashi’s involvement in the immigration working group was first reported by the Daily Beast.

One former senior administration official said that, given Miller’s clout in the West Wing, it would have been highly unlikely that he would have allowed Menashi to be foisted on him. Instead, he probably chose Menashi, the former official speculates, because the two have similar views on immigration.

Miller did not answer a Yahoo News query asking about his collaboration with Menashi.

Even with a tough hearing expected for Wednesday, Menashi will likely survive, since the Senate Judiciary Committee is controlled by Republicans. The GOP controls the Senate too, but Republicans are especially worried about Scott.

“If Scott isn’t onboard, that’s potential trouble,” said a conservative legal scholar familiar with judicial confirmation battles. This appears to be a widely shared view: Some Republicans are hoping that Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, who is facing reelection next year, will exert pressure on Scott to vote for Menashi. That would win Graham support from Trump’s base, which has sometimes been suspicious of him.

At the same time, efforts to lean on Scott could backfire.

Graham’s office did not answer a request for comment. Ken Farnaso, a spokesman for Scott, said that he and Graham had not spoken about the Menashi nomination. “As with every nominee, Sen. Scott does his own research and vetting to ensure that every person the Senate confirms is of the highest caliber,” Farnaso siad.

But even if Menashi might not prove the easiest nominee to shepherd through Senate chambers, conservatives are cautiously optimistic about his prospects. The White House associate who knows Menashi and has worked on many previous nominations remained optimistic in the days leading up to the hearing. Menashi is “very likely to be confirmed,” he predicted.

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Document reveals the FBI is tracking border protest groups as extremist organizations

How Atlanta's mayor turned her famous father's arrest into a passion for criminal justice reform

Felix Sater: Trump wanted to reveal my secret CIA, FBI work during the campaign

PHOTOS: Stunning images capture the relationship between man and elephant