Peter Jackson On His Four-Year Obsession That Led To ‘Get Back’ & Who Really Broke Up The Beatles

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

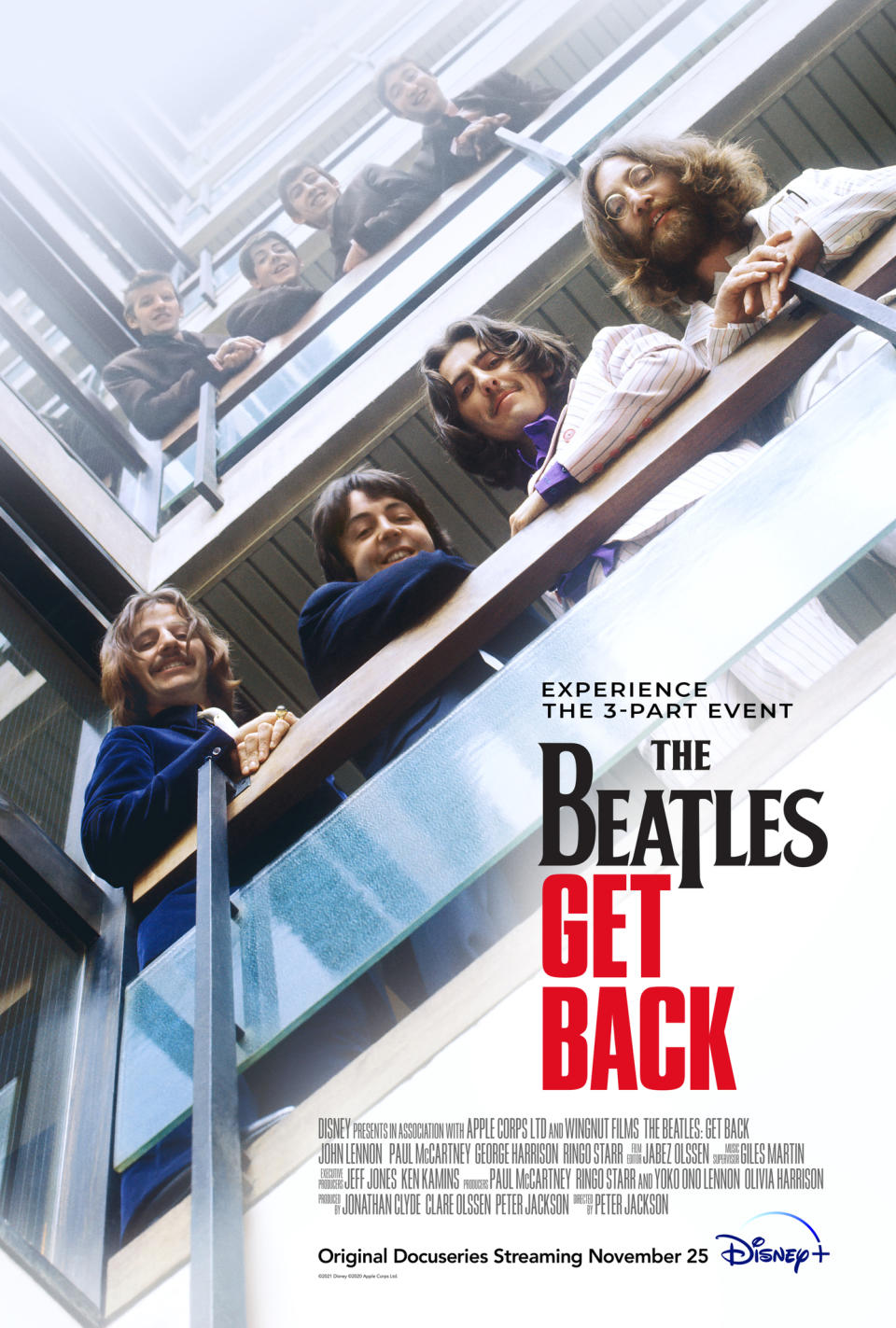

It’s not quite as arduous as Hobbits venturing to Mordor to destroy Sauron’s ring, but Peter Jackson’s immersed himself for four years to bring to life the end of the long and winding road of The Beatles. The result is the seven-hour The Beatles: Get Back, which Jackson culled and restored from 60 hours of studio sessions and a rooftop concert. All of it was shot in 1969 by Michael Lindsay-Hogg for his film Let It Be at a time when Apple forbade him from including much that created understanding and context of the group’s creative process and difficulties that led to estrangement and breakup. A fan of the hits from John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr since he was a pint-sized Kiwi, Jackson used the technical clean-up process that breathed life into his WWI documentary They Shall Not Grow Old to make it seem like you are watching live footage. The film will be shown in three parts on Disney+ from November 25-27. Here, he explains the monumental task and divulges who really broke up the band. Contrary to legend, it was not Yoko.

DEADLINE: Where were you in your life when you discovered The Beatles, and what did they mean to you then?

More from Deadline

'The Beatles: Get Back' Issues First-Look Clip At The Fab Four's Final Days

Disney+ Releases New Clip From 'The Beatles: Get Back': Band Learns "I've Got A Feeling"

Rich Fury/Invision/AP

PETER JACKSON: I was an only child and grew up in the ‘60s. I was born in ’61 and so was alive all the way through the time they released their albums. We had a gramophone thing, and [my parents] had a soundtrack album of South Pacific and Camelot and Mom was a bit of an Engelbert Humperdinck fan. I must have liked them on radio and television. My first real encounter with them was, I’d saved pocket money when I was 12 or 13. I was going into the city to buy a model airplane that I had my eye on and saved for. I passed the record shop on my way to the mall and there was a window display for the two albums — the compilation album they put together in the early ‘70s, one red and one blue, and I stopped dead in my tracks. I’d never seen those two photos side by side, them staring over a balcony. I went inside, I recognized some of the songs and I blew all my pocket money on the two albums. I still haven’t bought that plane. But I had two Beatles albums, I played them at home, especially when my parents weren’t around, and I slowly bought all the other albums. That’s how it began for me.

DEADLINE: The Beatles mythology had been picked over in myriad books and films. What convinced you there was enough new to make it worth your while and ours?

JACKSON: There was obviously enough footage to do incredible things. I just wanted to look at the footage because of the reputation of the period in The Beatles’ careers, the so-called Let It Be period. It was considered the breakup album. I wanted to look at the footage. If it had been all miserable, arguments and fighting, if it was all the stuff Michael Lindsay-Hogg was not allowed to put in his movie, I thought, “My God, what horrors am I going to be seeing here?”

DEADLINE: What did you find?

JACKSON: The exact opposite. It’s no mystery, really. The breakup and Michael’s movie happened in 1970, and this was shot January ’69, so it was filmed 15 months before. Michael made his film from exactly the footage I did. I had 60 hours of footage and 130 hours of audio. It was a big job that has taken me four years. At the end of January, Michael disappears with the footage and he has to edit his film. The Beatles don’t want to release the album until the film comes out, side by side. The Beatles, while they were waiting for the film to appear, they do the Abbey Road album, which comes out later, and soon after Abbey Road, they break up. Unfortunately for Michael, terrible timing. His film got this breakup rush unfairly plastered all over it. I’ve seen Let It Be in recent times. It’s not a breakup film; human psychology being what it is, everyone projected the breaking up they were reading in newspaper headlines, onto his film. It didn’t do the film any good at all. Seeing the original footage, it’s got drama, it’s not all play. They set out to achieve a project involving a long journey. It goes off the rails, it gets pear-shaped, and they try to figure out what to do. On the other hand, the best drama comes from things going wrong. I’m fortunate as a storyteller that it wasn’t all smooth sailing; otherwise the film would have been a lot more boring than it turned out. There were crises, and those show who The Beatles really are. What better way to reveal who people really are than when they have to deal with crazies of various sorts? And that’s what you see here.

DEADLINE: Was there some exceptional surprise that hit you and made you have to tell this story?

Disney+

JACKSON: Not initially because it was the culmination of 60 hours and you don’t really know what the story is. You look at it and it’s 60 hours of incredible stuff. We had to dig in and find the story. The story is usually contained in scripts, and this was real life, and it’s a period not very accurately written about. It’s got a notorious reputation which is actually false. It’s hard to find an accurate account. I had to eavesdrop and make my own determination what was the story and show it, day by day. It’s 22 days Michael filmed, the entirety of what was called the Get Back project which became Let It Be 15 months later. I wanted the audience to experience it like The Beatles did. They did something on a Tuesday not knowing it was all going to go wrong on Thursday. We are very much living their experience alongside them. That’s ultimately the film I ended up making.

DEADLINE: What connective tissue did you find between the process that your creative team goes through in mounting big movies and what you observed The Beatles going through as they created from scratch what would become a classic album?

JACKSON: It’s friendship, and trust. I’ve often thought that when we write the scripts I’ve done with Fran [Walsh] and Philippa [Boyens], you get to a point where you don’t have to tiptoe around people’s feelings or ego. You’re just three people, and if one comes up with an idea that is not very good, you can just say that’s not going to work and you move on together. The other thing is, it’s great when there are three people and, in this case, four Beatles. If somebody gets stuck, somebody else will have an idea. It might not be the right one, but it can spark another idea. You very much see the same thing onscreen with The Beatles. It’s very much the same deal.

DEADLINE: What was the most helpful observation you got from either Paul McCartney or Ringo Starr, the two surviving Beatles members?

JACKSON: One comment from Paul that I was happy to hear. … I wasn’t there, and I had to do a lot of compressing. I could have skewed it one way or the other, and when Paul saw it, he said, “Yeah, you captured exactly who we were at that time of our lives.” He recognized his three mates, and had no issues with the way I ended up showing them — which I tried to do with utmost honesty. I didn’t muck around or do any silly tricks to make anyone look different from who they were at the time.

DEADLINE: What was it like for them to watch what you did? John was taken from them abruptly, and George is also gone. Were they emotional?

JACKSON: Paul said something interesting. In the end, they got up on the roof to perform. The three in the front row and Ringo behind them. He said something I hadn’t thought about. He said, “When I was performing with The Beatles, John was beside me, but I couldn’t study the others. I can now watch how John played, how his fingers moved. I can study how George and see Ringo play, which he couldn’t because Ringo was at the back.” He loved watching his bandmates do their thing. Even though he played hundreds of hours with those guys, he couldn’t see what they were doing.

DEADLINE: In the footage I saw, Yoko Ono is omnipresent. She’s quiet, but always by John Lennon’s side. The rest seemed to accept her being there; they didn’t talk to her much. What did she bring John that helped him? We always heard Yoko broke up the band. What do you think?

Linda McCartney

JACKSON: Yoko didn’t break up the band. The band broke up over disagreements, with Allen Klein coming in to run their business affairs — which Paul didn’t agree with. The Beatles were always a band who always had a hard-and-fast rule that it’s four votes or it doesn’t happen. If all four weren’t in agreement, it would not occur, it had to be unanimous. For the first time in the history of The Beatles, it was three votes to one. John, George and Ringo wanted to bring in Allen Klein to run their business affairs, and Paul didn’t, and they said, “Well, Paul, Allen Klein is coming in because we are three votes and you are one vote. Paul tried to make it work and so did they, but it drove a wedge between them, and that’s why the band broke up. It had nothing to do with Yoko.

Yoko comes in and doesn’t interfere. She doesn’t express opinions, she’s quiet. She’s there because she and John are in love. There is no other complicating factor to it. John has to go to work and disappear for 12 hours, and he doesn’t want to disappear from her. So she comes and sits beside him. It’s love — nothing more complicated than that. She’s very respectful. She doesn’t talk to them, because engaging would take their minds off the job at hand. Once she starts to chat with them, it’s a disruptive force and she’s very respectful. She sits there, she knits, she reads books. Because they are focused on their work, they don’t talk with her, but she’s just in love with John. And she is very respectful. And her telling Paul to speed up the solo or giving George advice, that’s not who she is and was. That’s what I gleaned from the footage.

DEADLINE: In They Shall Not Grow Old, you took this dusty footage of men who fought World War I and brought them to life. What did that technology allow you to do here with this 50-plus-year-old footage?

JACKSON: I had different approaches in front of me. I could have interviewed all these people who were there in 1969 and are here now. You got Ringo, Paul, Michael Lindsay Hogg who shot the original footage. I took the opposite approach. I didn’t want that 50-year void to be discussed. I’d always fantasized as a Beatle fan that before I died, someone would invent a time machine. And when I got my trip in a time machine, I’d go back and watch The Beatles work. This was my opportunity. So I took away the 50 years; no interviews after the fact. It’s like we’re in the core of the studio, watching The Beatles. That was my dream, and to bring that alive, I needed to get rid of all traces of a film. I had to clean up the 16mm negative. Make it sharp, make it clear, get rid of scratches. Really you are taking the whole curtain away and you’re very much there with the Beatles. They tell their own story. I let their raw conversations inform it. They’re talking about what to do, what the Plan B is going to be. It doesn’t need a narrator. Their private conversations from 1969 are enough for us to follow the story.

Best of Deadline

Most Popular Netflix Movies & TV Series, Ranked By Total Viewing Time

Hallmark Channel 2021 Christmas, Haunukkah & Holiday Movies Schedule

2021 Holiday Movies, Shows On TV & Streaming For November & December - Updated Schedule

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.