Peter Bart: The State Of Dealmaking In Hollywood Is A Whole New Ballgame, Again

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A brilliant negotiator, Lew Wasserman was the ex-agent who presided over the vast MCA Universal media empire from his black tower. He favored black suits and austere offices and seemed to convey stress as he strolled about his kingdom.

Wasserman seemed always in a state of negotiation: He not only hammered out deals for new projects but also union and guild agreements for the entire industry and antitrust deals governing acquisitions like Decca Records. He even helped negotiate divorce settlements for the stars he once represented like Clark Gable and Myrna Loy.

More from Deadline

Historically, The WGA Is Overdue For A Strike, With Residuals Again A Key Issue Of Upcoming Talks

Los Angeles Dodgers Pitcher Trevor Bauer Reinstated, Team Has 24 Days To Decide His Fate - Update

Sean Connery Foundation Established To Honor Actor's Legacy Through Grants In Scotland & Bahamas

Related Story

Historically, The WGA Is Overdue For A Strike, With Residuals Again A Key Issue Of Upcoming Talks

Related Story

Los Angeles Dodgers Pitcher Trevor Bauer Reinstated, Team Has 24 Days To Decide His Fate – Update

Related Story

Sean Connery Foundation Established To Honor Actor's Legacy Through Grants In Scotland & Bahamas

Wasserman likely would have relished this Hollywood moment, because everything in Hollywood seems to be in a state of negotiation with everyone wanting a bigger piece of the pie. Writers and directors feel underpaid, their backends reduced, and are ready to strike for more. Actors feel marginalized by revised deal structures of the majors. CEOs feel tormented for over-optimistic revenue projections and for misleading Wall Street about the content costs of the streaming revolution.

The reason Wasserman would be comfortable amidst all this is that he survived, and prospered, through a relatively similar period of disruption five decades ago. Everything in Hollywood was changing as an entire new type of entrepreneur laid siege to the industry and inaugurated new ground rules for doing business.

Hollywood no longer belonged to the Jack Warners or Louis B Mayers. The proprietors of the studios were suddenly characters like Rupert Murdoch from newspapers; or Ted Turner, the “mouth of the South,” from broadcasting; or even Steve Ross, a onetime funeral director who owned a limousine company before assuming control of Warner Bros and Time Inc.

Facing new mandates and new personalities, virtually every artist in Hollywood seemed to decide to go into business for themselves. Writers like Joe Eszterhas or Shane Black no longer waited for script assignments; instead, they wrote their scripts for their own companies and put them up for auction, reaping as much as $4 million-$5 million per deal.

Directors like Steven Spielberg or Francis Coppola sought funding for their own companies, demanding ownership in the “content” they now created.

Indeed, the entire process of talent negotiation took on a sharply different perspective, with the players deciding to do their own negotiations rather than waiting for their representatives to serve – or unserve – them.

Curiously, as a then young newspaper reporter in Hollywood, I witnessed this transformation from a unique perspective. That’s because the media was occasionally placed in the midst of the negotiating.

It began with a chance meeting with a young press agent who was excited because he’d just signed the two most important pitchers in baseball: Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

“Why do pitchers need a press agent?” I asked him. “They get enough attention every time they win a game.”

“But they want to be movie stars, not pitchers,” said the press agent. ‘The Dodgers refuse to negotiate a good enough deal with them and won’t even meet with their agents, so they want to break away and become actors.”

“I find that hard to believe,” I said. “They’re stars.”

“But this is baseball and the ball clubs are old fashioned with their talent. I’m meeting the ball players for lunch so if you don’t believe me, why don’t you join us?”

Within a few minutes I found myself at the Brown Derby listening to the complaints of two very bright and articulate athletes who were rebelling against the tight-fisted negotiating style of their team’s management. They clearly hoped that my newspaper, the New York Times, would advance their cause – albeit inadvertently. They wanted million-dollar contracts over three years; the team was offering half that.

The upshot: the two were now in rehearsals for roles in a movie titled Warning Shot and were also pitching an ABC TV series. “I like the idea of creating something, not just tossing a ball,” said Koufax, who clearly was smart and ambitious.

With their help, I crafted a Times story about their negotiations, detailing their “asks.” I realized I was being used to a degree but it was a good story and their argument was a valid one.

The story ran and their employers panicked. The deals for the two pitchers improved radically.

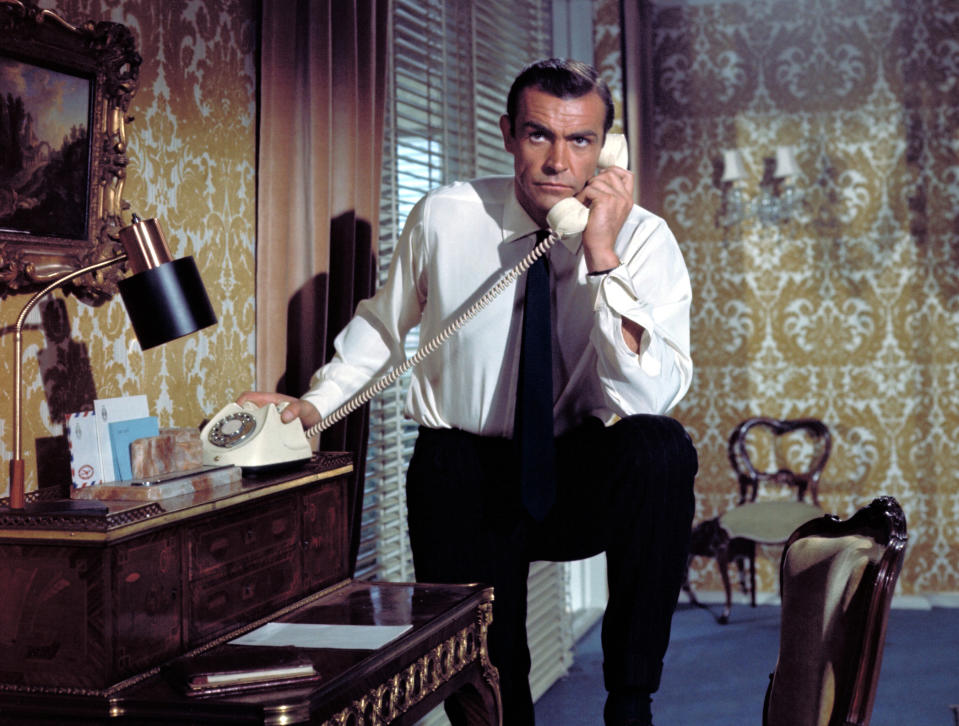

Within two weeks I received a phone call from another major talent. Sean Connery was angry. He had made two James Bond movies, had watched their grosses soar and had also studied the lucrative deals for a range of James Bond merchandise.

He now wanted to have a drink with me to discuss a “news story” about his career plans.

A sharp-witted man, Connery was candid about our odd relationship. He would give me an “interview” declaring his unwillingness to do further Bond pictures under the existing formula. He was instead considering a Broadway play.

The Bond producer, Albert “Cubby” Broccoli, would surely read the Times article and understand his dicey situation. He couldn’t afford to lose his star if the Times indicated this was a likelihood. Further negotiations were called for.

Again, my personal role was in question and Connery understood my concern. I was being used as a negotiating pawn. So was the Times. But it was a damn good story. And it was also true – Connery was thinking of walking.

Connery got his raise. He and I even had a subsequent drink to celebrate.

And I made a resolution: Given this new epoch of self-negotiation, I would henceforth remain on the sidelines. If a star, or a ballplayer, approached me with a proposal of this sort I would remind them to summon up their agent. If a new deal were hammered out, I would then write the piece as an innocent bystander.

Ultimately a sense of order re-established itself in Hollywood. The new proprietors began to fall back on more conservative ways of doing business. The writers and directors also were not doing that well with their newly funded companies and were irritated by the business demands of fundraising and financial disclosures.

As for myself, instead of writing about the arcane business practices of Hollywood, I went to work as a studio executive.

But I never succeeded in making a deal either with Connery or Koufax and Drysdale.

But I had great seats at their games.

Best of Deadline

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

2022-23 Awards Season Calendar - Dates For The Oscars, Golden Globes, Guilds & More

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.