Peter Bart: Critics Heap Honors On ‘70s Movies, Celebrating Moment When Filmmakers Were Hot & Studios Were Broke

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

They were “memorable” or “unforgettable” or even “life-changing.”

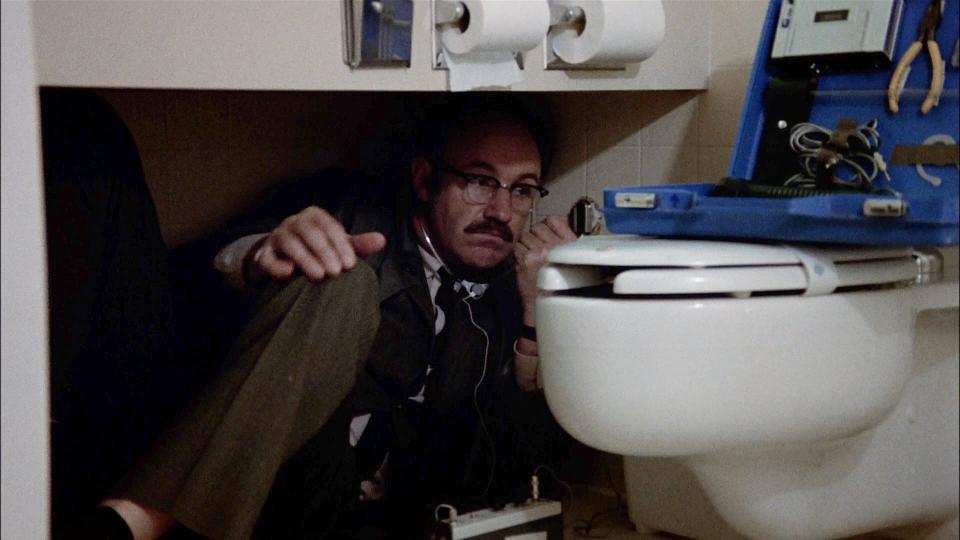

Each week it seems a ‘70s movie is singled out for special honors by cultural historians or critics desperate to avoid reviewing a new film. This week TCM faithfully focuses its 50th anniversary spotlight on The French Connection, replete with interviews and re-screenings.

More from Deadline

Peter Bart: Academy Museum Hopes To Illuminate Hollywood's Story - And Dramatize Its Founders' Role

Universal & Peacock Close $400M Deal For 'Exorcist' Trilogy; Ellen Burstyn To Reprise Classic Role

While the criteria for some of the “50th” celebrations might be open to question, this one seems well deserved. Billy Friedkin’s movie clearly had an important impact on the film culture, also brilliantly re-inventing the concept of the car chase. Equally important, it inadvertently was responsible for the creation of an even more successful and impactful movie, The Exorcist.

Everett Collection

The Warner Bros. management in 1971 knew it had a hot property in William Peter Blatty’s runaway best seller but was scared of Friedkin’s inexperience in the genre. The book was offered successively to Mike Nichols, Arthur Penn and even Stanley Kubrick, but all replied that the genre scared them, too.

When the studio read rave reviews of The French Connection, however, their fear of Friedkin instantly vanished, the green light flashing. Suddenly the filmmaker known mainly for shooting stage plays such as The Boys in the Band and The Birthday Party seemed ideal for action pictures — details on that below.

The ’70s celebrations in general, however, raise some troubling questions about that period. Are critics and cineastes sentimentalizing that epoch because they’re still infatuated with its rebellious aura — the drugs, the music, the sex? Were the studio managements of that moment truly committed to supporting innovative filmmakers, or were their choices — and successes — an accident of history? And do young filmgoers today even care?

In retrospect, the Oscar rituals of the ‘70s also reflected the era’s disjointed subtext: Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight surprisingly was honored for its “Best score” in 1973, even though the movie had been released in 1952 but ignored then because of Chaplin’s supposed communist sympathies and provocative personal life. Oscar acceptance speeches of that moment were equally perplexing — witness Sacheen Littlefeather’s surprise appearance in 1972, rejecting Marlon Brando’s award at his behest.

The Best Picture selections of the ‘70s also seemed erratic. Honors heaped on The Sting in 1974 represented retroactive recognition of the Paul Newman/Robert Redford chemistry after their Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had been shunted aside five years earlier by Midnight Cowboy.

In the same vein, the recent wave of 50th-ish anniversary celebrations of The Graduate and Cabaret seem like makeups for their Best Picture snubs. Were they ahead of their time?

Everett Collection

Directors of that period generally display a deep skepticism of the ailing studio system, circa 1970s. Francis Coppola argues that The Conversation never would have been funded had it not been for the outlaw venture called the Directors Company, hatched by a feuding Paramount management.

Coppola, Friedkin and Peter Bogdanovich were granted the right to greenlight any film budgeted below $3 million, thus conveniently resolving Paramount’s decision-making blockage. Despite two hits, the Directors Company imploded after two years.

To Friedkin, the most important weapon in the filmmakers’ arsenal was easy to pinpoint: The studios were impoverished.

“They were running out of assets, and that became our biggest asset,” he recalls. “At Fox, Richard Zanuck was about to walk the plank and the studio had run out of money, so he figured he’d lavish the last $1.7 million in his budget on The French Connection,” Friedkin observes. “There was a pervasive sense of desperation across Hollywood.”

Everett Collection

The surviving executives at Fox after Zanuck’s exit never “got” the script, even hated the title and were appalled by the car chase — which had never been scripted or storyboarded. Friedkin obtained no official approvals from the City of New York for his epic chase scene and quietly slipped bribes to transit officials to persuade them to look the other way.

“Orson Welles had told me that making a movie was like playing with the biggest Erector Set a kid ever had,” Friedkin recalls. The young filmmaker sped through city streets at over 90 miles an hour, even racing an errant subway train, while admittedly risking the lives of crew and pedestrians.

While the scene ended up surpassing the excitement of even the classic chase in Bullitt, to Friedkin it still failed to match the daring of Buster Keaton’s chases of the 1920s. “Keaton was the master of that art form,” he concludes.

Achieving a surprise box office hit with French Connection, Friedkin went on to astonish audiences with his head-spinning Exorcist. It was a film that ultimately was celebrated by critics and networks, labeling it as “memorable” and even “life changing” — like the thrilling chase movie that gave it life.

Movies never again were quite the same, as we will be reminded by the commemorations 50 year later.

Best of Deadline

Most Popular Netflix Movies & TV Series, Ranked By Total Viewing Time

Hallmark Channel 2021 Christmas, Haunukkah & Holiday Movies Schedule

2021 Holiday Movies, Shows On TV & Streaming For November & December - Updated Schedule

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.