A Pellicano Target’s Second Act

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“So we’re down in Uvalde, right?” Anita Busch tells me in one of the lengthy, emotional conversations we’ve had this summer. She is describing the aftermath of the 2022 Texas mass shooting in which 21 grade-school students and teachers died. “I have the team down here in Uvalde for a fifth time. And we’re getting ready to head over to Nashville to help over there,” she says. “As soon as we hit the road, I get word that there’s been a mass shooting at the outlet mall in Allen, Texas. So we divert over there instead.”

Back in the late 1990s, when Busch was a leading entertainment journalist, her points of reference all centered around Hollywood: “Paramount.” “Fox.” “CAA.” But this is her road map now: “Uvalde.” “Orlando.” “Allen” — scenes of the unthinkable yet increasingly commonplace mass-casualty shootings that have thrust the country into a seemingly unending cycle of terror, grief and helplessness.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

It’s the helplessness part that Busch can’t live with. After her cousin Micayla Medek was murdered at age 23 in the 2012 Aurora movie theater shooting that took 12 lives, Busch — whose journalism career was sensationally derailed in 2002 after PI to the stars Anthony Pellicano ordered an anonymous threat on her life — found a new purpose.

The result is VictimsFirst — a nonprofit determined to revolutionize and accelerate the way help is funneled to the victims of such tragedies. The golden rule of VictimsFirst is that 100 percent of all donations go directly to shooting victims and their families. Too many other fundraising efforts, Busch says, have gone everywhere but.

Busch learned that the hard way when she tried to get a few thousand dollars for Micayla’s father, who was too distraught to work and was told that despite having raised $5 million, there was nothing available in the Aurora Victim Relief Fund to help him. Caren and Tom Teves, whose 24-year-old son, Alex, was murdered in Aurora, were among the victims who signed an open letter, authored by Busch, questioning why families had only received $5,000 each.

“It was truly unbelievable,” recalls Tom. “We fought and fought and fought. Eventually the governor got involved and a couple of congressmen, and they ended up turning the money over to the victims. But who the hell needed that at that point in your life?”

Busch helped shine a light on how some of these other nonprofits work, says Caren. “They collect money and put it to other places,” she says, “and it’s all under the guise of collecting money for victims. When you send $100 over to the victims of Uvalde, you want to make sure that’s who it’s going to.”

Busch’s efforts at rewriting the mass-shooting playbook — and she has literally compiled and self-published a best-practices guide — have proved so effective that they earned her a call from the White House, during which two Biden administration officials, a FEMA officer and a Boston University researcher grilled her on how to better serve the needs of victims. By the end of this fiscal year, Busch says that VictimsFirst will have donated more than $10 million in direct aid since officially becoming a nonprofit in 2021.

“I literally go back and forth between mass shootings around the country,” says Busch, 62, who frequently needs to pause conversations to answer the emergency help line on a dedicated cellphone she carries with her at all times. “I’m leaving Friday to go to Orlando.”

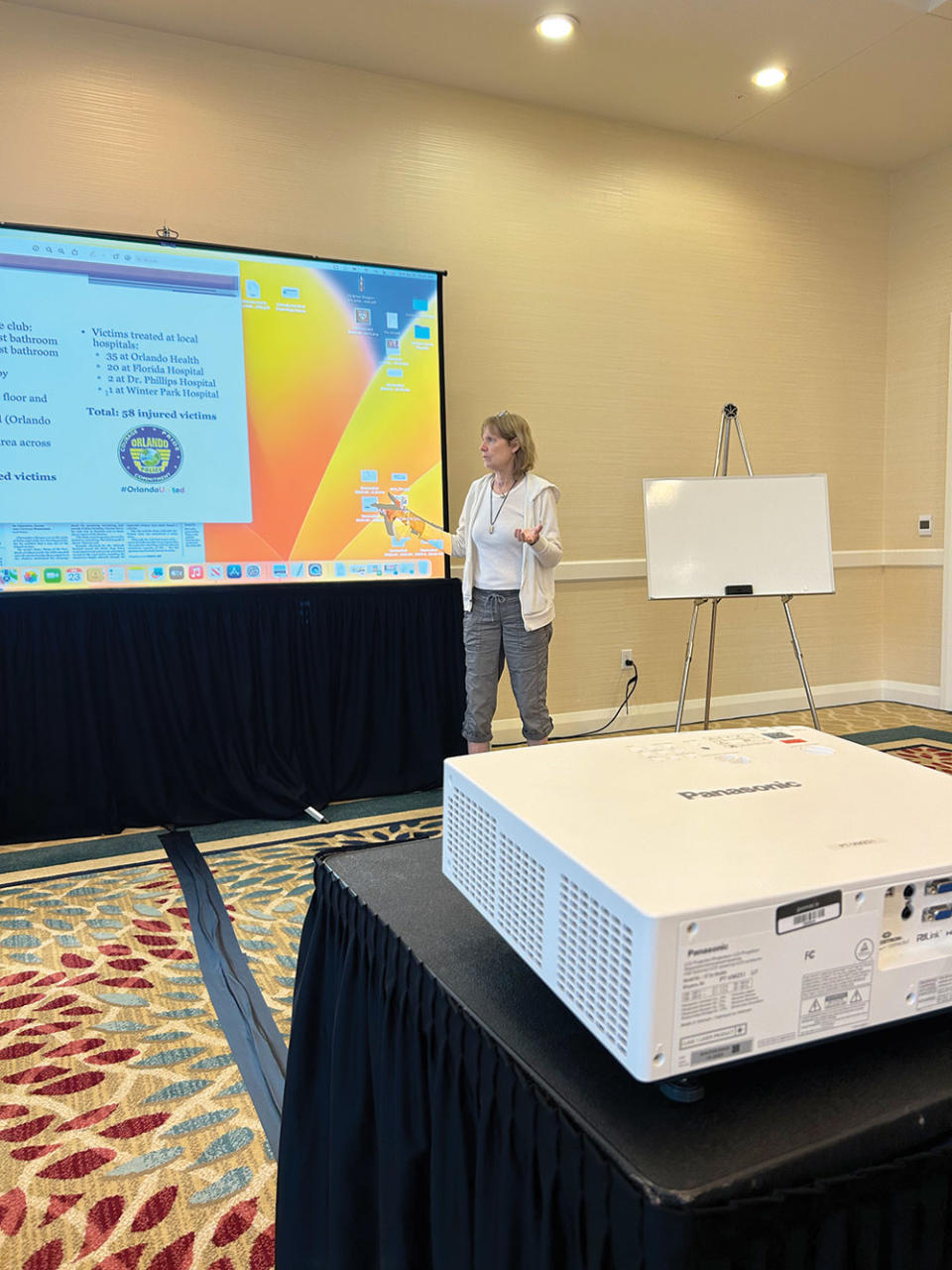

The Allen shooting, which killed eight and injured six, will mark the 47th that Busch and her rapid response group have confronted in the 11 years since Aurora. In that time, she has borne witness to unfathomable carnage. Several on the VictimsFirst board of directors — there are six board members and an additional leadership council of 33 — are themselves victims of mass shootings. “Tiara [Parker] was shot three times in Pulse [the nightclub shooting in Orlando], and her 18-year-old cousin died in her arms,” Busch says. “Javier [Nava] was shot in Pulse and almost bled out. Five of his friends died on the dance floor.”

Victims could be in dire need of just about anything — from rent to food to trauma therapy to surgeries. For example, Busch says, a woman shot in the face and abdomen during a 2021 Father’s Day shooting rampage in Tampa, Florida, was recently served with a $40,000 hospital bill. “We are working to get the bill removed, absorbed by a philanthropy unit,” Busch explains. “We’ve helped people who have these AR-15 softball-sized wounds in their body. We know people who have gone through 50 surgeries. We know that it’s a lifetime of pain and suffering. We’ve helped [keep] people from going homeless. We’ve helped [keep] people from committing suicide. We’ve done a lot. If you can think of it, we’ve probably done it.”

A new program from VictimsFirst, Make New Memories, fashions itself after the Make-A-Wish Foundation. An 11-year-old girl who has undergone 60 surgeries after being shot seven times in Uvalde — and witnessed her classmates and teachers perish in front of her — is one of its first beneficiaries. “We recently got her Taylor Swift tickets because a donor wanted to sponsor a Make New Memories event,” Busch says, adding that the sponsor is covering hotel and airfare.

“Whenever Anita asks, I show up,” says Casey Affleck, 47, who — eager to do something — linked up with Busch following the Aurora shooting and has worked with her on subsequent tragedies. He helped her raise funds so that survivors of Parkland, the deadliest high school shooting in U.S. history, could travel to the historic March for Our Lives in Washington, D.C. “I have seen what she’s doing is great and she doesn’t make a big show of it. She’s just quietly helping lots of people, and I really admire her.”

***

The seeds of Busch’s second life as a victims’ rights activist were planted in early childhood, in Granite City, Illinois, a steel mill town that had “a big orange cloud over it from air pollution — the city assured us we were not going to get sick,” she says with a laugh. Her mother was a real estate agent and a “Kroger lady,” sampling grocery items on local TV. Her father was an executive at Sunline, the candy company behind SweeTarts and FunDip.

“My father was an incredible man,” she says. “He helped a lot of kids who didn’t have guidance in their lives. He was a Scout master. He helped get funding for the first school for autism in Illinois. And he always fought for the underdog. I always called him ‘my Atticus Finch.’ ”

From a young age, she found herself drawn to journalism, interviewing siblings and friends for imaginary newspapers. By her 20s, she had moved to Chicago and was working at Advertising Age. But something about Los Angeles beckoned — “I don’t know why, but I always knew I was supposed to be there” — and when a job opening for a movie marketing reporter opened up at The Hollywood Reporter in 1990, she leaped at the opportunity.

Busch arrived in L.A. without a single acquaintance in a town that’s all about who you know. “I remember going to the library and just reading and reading,” she recalls. “I thought I was going to get fired every single day at The Hollywood Reporter because I didn’t know the business.” But she began landing scoops. The first was about Young Frankenstein star Peter Boyle suffering a stroke. Then came a buzzy story on Orion Pictures’ groundbreaking marketing strategy for a new sci-fi film, RoboCop.

Her profile started to rise. On any given night throughout the ’90s, Busch might be spotted playing pool in a bar with then-Universal head Ron Meyer or engaging in a tense conversation with then-Disney chairman Michael Eisner at a corner table at the Peninsula Hotel. Gossip columns started taking note of her colorful persona, with anonymous sources weighing in with equally colorful descriptive — everything from “brilliant” to “eccentric” to “paranoid.” (“I’m a screamer in the office, not on the phone,” she told Salon in 1997.) Most of all, Busch had a reputation for taking on the scariest players in town. One gossip item that made the rounds at the time: CAA’s fearsome ruler Michael Ovitz once sent her a gift-wrapped bottle of MSG, to which she was allergic, accompanied by a note that read, “Enjoy.” (Busch won’t discuss the incident, citing a legal settlement with Ovitz, but in a 1997 Salon interview, she said, “I think he meant it as a joke.”)

In 1999, after a high-profile stint at Variety that left her sparring publicly with its then-editor Peter Bart — The New York Times around that period said she was “as feared by executives as she was relentless” — Busch was offered the top job at THR. She took it and would be ruffling feathers by year’s end, publishing a fiery op-ed denouncing the “loathsome” Fox release Fight Club. “The film is exactly the kind of product that lawmakers should target for being socially irresponsible in a nation that has deteriorated to the point of Columbine,” Busch wrote, citing the notorious school shooting in 1999. The editorial so infuriated Fox, it pulled all advertising from THR — incensing Bob Dowling, THR‘s publisher at the time.

Busch later quit after Dowling, who died in December, interfered during a fraud investigation into George Christy, THR‘s longtime society columnist, by David Robb, the outlet’s own labor reporter. “I caught George Christy ripping off SAG,” recalls Robb. “He was claiming he was in movies that his friends produced, but he wasn’t. So he could get pension and health benefits. Bob didn’t want to publish it. So I left in protest, and then Anita left.” The story was eventually published by the fledgling online outlet Inside.com, and Christy — who died at 93 in 2020 — was “removed from his job,” as a New York Times report put it, “pending investigations.” His column never returned. Says Busch of the Christy imbroglio: “I got subpoenaed. I had to go in and talk to the FBI and bring any documents that would pertain to this possible crime. It was just a very weird time. I couldn’t believe it, honestly.”

Things were about to get much weirder. After freelancing at The New York Times, where she wrote six articles chronicling Ovitz’s failing Artists Management Group — his comeback attempt after being ousted as president of Disney in 1997 — Busch was hired on contract at the Los Angeles Times in June 2002. “Dean Baquet called it the ‘coach and play’ position,” she says, referring to her former editor who later served as the top editor of The New York Times from 2014 until 2022. “I’d mentor the younger people and then also report.”

Baquet quickly assigned Busch to investigate how Jules Nasso, a B-movie producer with ties to the Gambino crime family, had come to be credited on a number of Steven Seagal films. “It was basically a profile of how, through Warner Bros., this all came together,” recalls Busch. “How did some of these people get on the set? I was talking to a lot of different people not normally found in Hollywood.”

On June 20, while Busch wrote out a list of questions for Seagal, a knock came at the door of her Stanley Avenue home in L.A.’s Mid-Wilshire district. It was a neighbor telling her to look at her car, a silver Audi. Busch threw on some clothes and went outside. “The neighbors were gathered around my car,” Busch recalls. “I thought, ‘That’s odd.’ ” She noticed a tray on the windshield holding something wrapped in plastic. It was, it turns out, a dead fish, a red rose clenched in its mouth. She then noticed a golf ball-sized hole in the windshield — to this day she doesn’t know if it was made by a hammer or a bullet — with a sign beside it containing a single word: “Stop.” Busch was later told by the FBI that the gesture was an “old Mafia death threat.” The following day she received an anonymous phone call that a private investigator planned to rig her car to explode the next time she started it.

Thus would begin to unravel the sordid tale of Pellicano, a Chicago-bred fixer whose clients included some of the most powerful players in Hollywood — Ovitz, former Paramount chief Brad Grey and celebrity lawyer Bert Fields, among them, plus major stars like Chris Rock and Michael Jackson. Extensive phone-tapping was one of his calling cards. So was the baseball bat he stored in his car trunk.

Even as some of Busch’s colleagues snickered at the Godfather-esque turn of events — with a few even questioning if she had made it up entirely — the FBI took the threats seriously. It did not take long before authorities determined the fish was put there by a Pellicano subordinate named Alexander Proctor. After Proctor was detained, he led them to Pellicano. A raid on Pellicano’s office in November turned up two hand grenades, a wedge of C-4 plastic explosive, thousands of pages of wiretap transcripts and thousands more hours of illegally recorded conversations stored on computer disks.

Busch, meanwhile, caught wind of other attempts to derail her work and life. At first, the signs were subtle, if unsettling: She recalls returning to the L.A. Times offices to find a mountain of Seagal files, which she had left a mess, tidily stacked at the corner of her desk. The touch-tone phone system she used to access her bank account mysteriously stopped working. Then, she says, a disturbing message flashed on her computer monitor — “YOU DON’T KNOW SHIT” — right before a virus wiped out her entire hard drive, containing a lifetime of her own musical compositions.

What she chalked up as a road rage incident she now suspects was a targeted attempt to run her off the road. Ned Zeman, a reporter for Vanity Fair also covering Seagal, experienced a similar terrifying encounter when a 20-something man pulled up to him near his home on Laurel Canyon Boulevard, pointed a pistol at his face and said, “Stop.” He then pulled the trigger — it clicked but did not fire — and said, “Bang.” Recalls Zeman: “I thought I was getting carjacked or something. So I stood frozen for a few minutes after the car sped off. Once I caught my breath, it hit me that this reminded me of Anita’s incident and it all seemed a little Get Shorty.” Seagal has denied he was responsible for any of the threats.

Advised by the FBI not to remain at her home, Busch says she spent a night at her parents’ place in a gated community, only to discover two men in a parked car outside, both of whom emerged from their vehicle to examine the underside of her car.

“These were the worst days of my life,” recalls Busch, emitting a heavy sigh. “Every little noise set me off. I couldn’t sleep.” By December, the FBI confirmed that her phones had indeed been tapped. “Rumors started spreading about the wiretapping,” she recalls. “Nobody wants to talk on compromised lines. I tried to continue on as a journalist until I just couldn’t anymore because it was impossible to be on the other side of the story. Bottom line — I thought I was going to be killed.” Panic set in. Busch thought it best to leave Los Angeles and checked into the Warwick Hotel in New York City. The phone to her room rang in the middle of the night, but the party on the other end said nothing. She returned to L.A. in February: “And that’s when it happened.”

Busch has never spoken publicly about what occurred next. On a chilly February evening, in a dark L.A. parking garage, Busch says she was “brutally raped” by one man while another looked on. “I was given a strong message by them, which was: ‘If you report this, if you don’t stop helping law enforcement, we are going to come back and kill you or harm your family.’ And I believed it 100 percent,” she says.

Busch did not report the rape to police, saying she was “too petrified” to do so — and concerned that her ailing father, who had a heart condition, might not survive learning of her attack. But she did tell other family members and friends in the weeks and months following the attack, including her former colleague Robb, who corroborates the details with THR. She also told her former assistant Susanne Wigforss. “I was completely shocked,” says Wigforss from Stockholm, where she has lived since 2002. “She started to cry because we talked about everything, the case, everything. And she just said, ‘I was raped.’ It was really, really horrible. I’ll never forget it. I was just shocked.”

The rape resulted in a concussion and back trauma that left Busch bedridden for 14 months and in a wheelchair for nearly five years. While her health and mobility woes became widely known, only a handful of her closest confidants knew the real reason. “I had to literally learn how to walk again,” she says. Her hair turned gray and fell out, and she developed stress blisters on her fingers. Twenty years later, she will park a mile away if it means avoiding a parking garage.

Because the rape ended with a warning, Busch says, “there’s no doubt in my mind that it had to do with the whole Pellicano case.” But she stops short of laying the attack at Pellicano’s feet. “It could have been dirty LAPD cops. It could have been anyone. I don’t know who it was,” Busch says. Reached for comment, Pellicano, 79, tells THR, “I had nothing to do with that, nor would ever have anything to do with something so despicable,” adding with regards to her work with VictimsFirst, “I’m very proud of Anita for doing this, and I wish her all the luck in the world and all the people that she’s helping.”

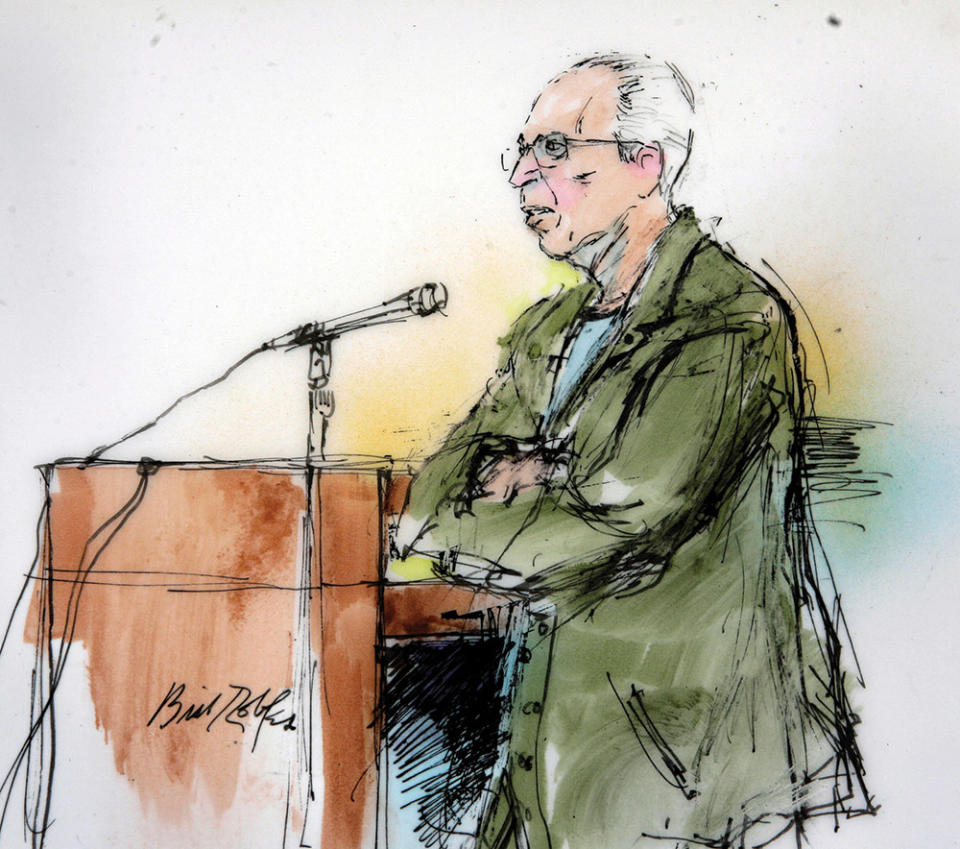

Following the raid on his office, Pellicano was jailed and remained in custody until his 2008 trial, during which he represented himself. In a statement delivered at that trial, Busch said, “You not only violated my privacy and that of my family and friends, but you violated the privacy of a journalist and her sources, undermining the very fundamentals of my profession. This attack was also on journalism and a newspaper’s ability to gather the news.” She continued, “After these threats, I was afraid to come and go from my house. I was afraid to sit in my car for even a moment out in the street for fear that a car would speed up on me again, block me in and this time I would be killed. And that was a catch-22 because I was also petrified to turn over the engine of my car for fear that it would blow up. So, I would sit there and cry and pray and beg, ‘Please God, I want to live.’ … And when I didn’t blow up, I’d wipe my eyes and go on to work at the L.A. Times and face the snickers from the disbelievers.”

Pellicano was ultimately convicted of wiretapping and conspiracy to commit wiretapping in the Federal District Court in Los Angeles. He was sentenced to 15 additional years behind bars and a $2 million fine. He was released in March 2019 and currently lives in West Hollywood, where he is back in business. (“Trouble shooting, problem resolution, crisis management,” reads the Pellicano.com homepage, where a flapping pelican serves as the logo.)

Three other men were convicted at the trial: Ex-LAPD officer Mark Arneson, paid to run illegal criminal background checks for Pellicano, was sentenced to 10 years. Ray Turner, the ex-Pacific Bell technician who helped Pellicano set up his wiretaps, also received 10 years. And Abner Nicherie, who hired Pellicano to wiretap a business adversary, got 21 months. At a separate sentencing, Kevin Kachikian, the nerdy, Birkenstock-wearing computer programmer who designed the software that illegally recorded the phone calls of Sylvester Stallone, Garry Shandling and CAA’s Kevin Huvane, among countless others, was sentenced to 27 months.

***

“I had prayed to become strong again so I could help other victims of crime,” says Busch. “I said, ‘If I get strong again, I will never stop helping.’ ” And Busch has held true to her word.

In 2018, she settled a lawsuit with Ovitz, whom she accused of hiring Pellicano. Details of the terms became public some time later when Ovitz sued his insurer, Fireman’s Fund Insurance Co., for having only paid out $2 million of a $13 million settlement to Busch. While she cannot speak about the case, multiple sources confirm that Busch has contributed her own savings toward her work with VictimsFirst.

But there have been other angels along the way. One was Shandling — whose $100 million lawsuit against his former manager, the late Brad Grey, made him one of Pellicano’s prime targets for wiretapping and reputation-smearing. “Garry and I had many late night talks,” says Busch, who describes the late comic as a brother figure. “Garry suffered a lot. We made a pact that we would try to make sure this didn’t happen to anybody else.”

Years later, during one of those conversations, Busch mentioned a family on the verge of bankruptcy. “One son had been shot and killed in a school shooting, and the other son needed surgery. The mother had no help. I had just hung up with her thinking, ‘What am I going to do? And Garry said, ‘What does she need? I’ll take care of it.’ And he did. Nobody knew about that.” She says Shandling’s sudden death — he died in 2016 at age 66 of a pulmonary embolism — “destroyed me because I lost my confidant and a great friend. He was family.”

Another major loss was George Shapiro, the legendary comedy manager and Seinfeld executive producer, who Busch says donated to “many, many mass shooting families” over the years, including victims of Newtown, Connecticut, before his death in 2022. “George understood, like, ‘Oh my God — we have to help. We can’t let this person not stand again. We have to help them stand again.’ ” That same year, Judd Apatow and Beck co-hosted a VictimsFirst benefit show at Largo that also featured performances by Jack Black’s Tenacious D and Dave Grohl. Busch’s connections at Sony Entertainment led to a donation of 180 noise-canceling headphones for the survivors of Uvalde, to reduce the trauma of July 4 fireworks.

But the majority of the funding for VictimsFirst has come from outside show business. “I don’t think a lot of Hollywood knows what I’ve been doing, to be honest,” says Busch, who relies on smaller private donations made through her website and “corporations who see our work and want to support us.”

Busch leaves the politicization of mass shootings, and advocating for gun control and assault weapons bans, to others. “We are nonpartisan,” she says. “We don’t care if you’re red or blue. If you’ve been directly impacted by a mass shooting, we’re there to help you. Period. We do have personal opinions about this stuff. Strong personal opinions. Yes, we have gun owners in our group. It’s not about that. It’s about trying to bring back humanity. We’re here to help each other through life. All of us are put on this earth to help each other.”

And with that, she excuses herself. Her victim hotline is ringing, and she needs to take a call about setting up a K-12 remote schooling program for the children of Uvalde who are too traumatized to return to the classroom.

Editor’s note: This story was updated on Sept. 29, 2023. The original version stated that two men raped Bush. The second man was an onlooker. The story has been corrected.

This story first appeared in the Aug. 16 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Meet the World Builders: Hollywood's Top Physical Production Executives of 2023

Men in Blazers, Hollywood’s Favorite Soccer Podcast, Aims for a Global Empire