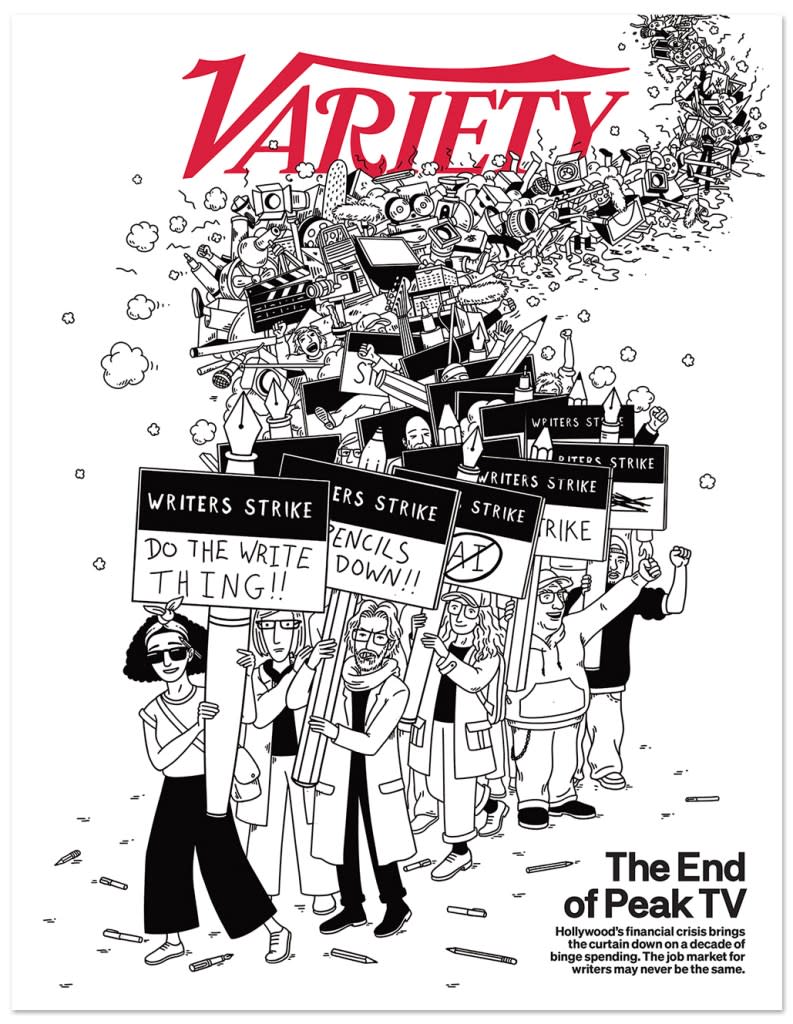

Peak TV Has Peaked: From Exhausted Talent to Massive Losses, the Writers Strike Magnifies an Industry in Freefall

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The tipping point has finally arrived. After years of heady growth, heightened demands and unpredictable development and production schedules, seasoned TV writers are feeling the burn and yearning for the structure of simpler times, before streaming changed everything. As striking Writers Guild of America members gather daily on picket lines in Los Angeles and New York, the realization of how much has been lost amid the unprecedented spike in episodic production has come into sharp focus.

“I miss the predictability of pilot season,” says Cindy Chupack, a veteran writer-producer who is a two-time Emmy winner for her work on “Modern Family” and “Sex and the City.” Chupack adds that these are words she never thought she’d say — or even think. And she’s not alone.

More from Variety

How SAG-AFTRA Talks Collapsed: 'I Was Taken Completely By Surprise,' Union Chief Says

Ted Sarandos Says SAG-AFTRA Asked for 'Levy' on Every Netflix Subscriber

SAG-AFTRA Alleges 'Bully Tactics' as Studios Suspend Negotiations

Since the writers strike began on May 2, the unintended consequences of the ramp-up in series production during the past dozen years have been laid bare.

The phrase “Peak TV” emerged around 2015 as a description of television’s endless appetite for original series. Now, there’s one thing that writers and their estranged employers agree on: Peak TV has peaked. The talent pool has been stretched beyond its breaking point, and so have most of Hollywood’s balance sheets. The entertainment industry in aggregate can’t afford to keep producing content at the pace of recent years, as evidenced by the astounding financial losses reported and cost-cutting campaigns underway at Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Paramount Global and to a lesser degree Comcast.

“You already have major legacy media companies that are struggling with pretty sizable streaming losses,” says Rich Greenfield, media analyst for LightShed Partners. “The challenge right now is that all of these companies are firing people and shrinking. There couldn’t be a worse time for a strike than right now. Yes, they save some money on not producing stuff in the short term, but the reality is these are increasingly challenged businesses. Linear TV is not doing well,” he says.

Greenfield’s view is echoed by a top literary agent who has watched closely as spending on film and TV content has been curbed across the board, even at the largest streamers, which are insulated from the pain spreading across traditional Hollywood.

RELATED: If SAG-AFTRA Goes Out, How Fast Will WGA Go Back in to Negotiations With AMPTP?

“Old media is in the worst position, including Disney,” the agent says. “Netflix, in the way that they’ve gobbled up local production and gotten global hit shows out of it — that can sustain them forever with the WGA sitting out. With Apple and Amazon, they’re not content companies. One makes phones and computers, and the other brings your groceries, and that’s always going to be their bread and butter. If their content pipeline slows down, it’s not going to lead to less Apple subscribers or less Prime subscribers.”

The solidarity SAG-AFTRA demonstrated with the WGA on picket lines has became loud enough to dramatically affect the Emmys’ FYC season. The fear of Hollywood enduring a double strike has become all too real during what J.D. Connor, associate professor of cinematic arts at USC, calls the “hot labor summer of 2023.” He predicts it will spur more merger and buyout activity among smaller outfits such as Lionsgate and AMC Networks.

“It is one of those situations where, once one or two of the dominoes finally fall into place, I expect to see a large wave of new consolidations, of acquisitions, barring a Biden administration antitrust activity that we haven’t seen yet,” says Connor, who specializes in contemporary Hollywood and studio economics.

Likewise, one former broadcast executive sees the niche, slow-to-grow streamers having the hardest time once the strike is over: “I think people start saying, ‘Well, where’s the shows? I don’t need this, so I’ll cancel this service.’”

As whispers spread throughout Hollywood about who will live and who will die by the writers strike, these companies remain radio silent on when they think the strike will be — and, financially, will need to be — over.

“The most surprising for me is just how no Hollywood executive seems to be standing up saying, ‘I’m going to take the lead in resolving this,’” says analyst Greenfield. “You haven’t seen Bob Iger, David Zaslav, Shari Redstone, Ted Sarandos — nobody is stepping up and saying, ‘Let’s get this resolved,’ which is fascinating.”

Story continues below.

There is no doubt that the TV content landscape will be very different once the strike is settled. The work stoppage has set off a domino effect among delayed shooting schedules that will complicate the best-laid plans of networks and streamers for months, if not years. But even without the strike-induced disruption to the content pipeline, the volume of scripted series orders is expected to drop by double-digit percentages in the coming years.

In 2022, mainstream TV networks and platforms delivered a record high of 599 total English-language adult scripted TV series, according to the annual industry benchmark compiled by FX Networks. That compares with 182 in 2002, the year FX announced its arrival as a major player with the police drama “The Shield.” The success of “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad” — two beloved dramas that transformed the fortunes of the once-sleepy movie channel AMC Network — added more demand in the late 2000s among cable networks that were then flush with profits. In 2012, just before “streaming” became synonymous with “television,” the industry’s aggregate original series count hit 288, per FX.

But the greatest catalyst for content growth was Netflix’s big splash in February 2013 with its $100 million, two-season bet on “House of Cards,” the edgy political thriller from director David Fincher and writer Beau Willimon. With its explosive debut, the show introduced viewers to the radical new concept of binge-watching by making a full season’s worth of episodes available on premiere day. And that big-bang moment, so quickly embraced by viewers, led to the launch of Disney+, Apple TV+, Max (and its HBO-branded predecessors), Peacock and Paramount+. Netflix’s example also drove Amazon to pump up the volume at Prime Video.

Ten years later, amid labor strife and the ragged business landscape, the original series count number for 2023 can only fall. Even Netflix is easing the throttle on overall content spending as the company begins to deliver steady profits after years of investment.

With the changes in the industry, there’s been so much that has impacted our livelihoods and the health of this business,” says a veteran media executive who has been allaying the fears of younger colleagues. “We’ve known those changes are going to continue to come until there is some sort of financial stability for all the studios. And I know that it’s much broader than the strike, but it’s all impacting at the same time.”

Hollywood’s old guard has been forced to make draconian cuts in the turbulent post-pandemic era, punctuated by Disney’s pink-slipping of 7,000 staff positions. Warner Bros. Discovery and Paramount have also made deep cuts. And they’re all yanking shows right and left from cable and streaming platforms to save money on basic residuals and music licensing costs. Apple and Amazon remain outliers, bolstered by their respective trillion-dollar market capitalizations, but even the deepest of pockets have their limits.

In the weeks leading up to the strike, Netflix, Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery and other mega media companies assured shareholders and subscribers that their content pipelines are stocked, that they are well positioned to roll out TV series through the end of the year, some through the first quarter of 2024, and that a writers strike over the summer won’t ultimately affect their bottom lines.

But that was before the WGA took an aggressive and tactical approach to mounting picket lines on location shoots to ensure that even shows with completed scripts in hand on May 1 would not be able to complete production orders on schedule. Observers say the hardest blow the WGA strike can deliver will come over the long term, when the cost of grappling with shuttered productions and partially completed seasons will be enormous.

The WGA’s forceful action dovetails with a surge of anger among rank-and-file SAG-AFTRA members that has the performers union on the verge of an industrywide strike for the first time since 1980. SAG-AFTRA’s complaints are more evidence of how employment dynamics have changed for the worse for working Hollywood.

For decades, pilot development episodic television was done assembly-line fashion on a steadily predictable schedule. The cap gun would go off in January, when each of the major networks would select two dozen or so scripts to greenlight to pilot production. Back then, industry insiders would grouse about the rushed pace of producing make-or-break series pilots in a three-month period in advance of the May upfronts. It was nonetheless a process that imposed a schedule for production and decision-making. In hindsight, it feels to many like a level of discipline that has been missing from the Peak TV binge.

“It was all or nothing, but at least you knew where you stood after a pilot season,” Chupack reflects. “Now you can wait so long to hear anything on a greenlight and you can go months and months between seasons if you do get picked up.”

The focus on delivering episodes for a traditional September-May television season also dictated a schedule of production that was punishing but fulfilling. The many picket-line reunions that have been staged in recent weeks have reminded seasoned writers of the camaraderie of working on 22-episode-per-season series that enjoyed long runs on air. The short-order and short-lived shows of today have some feeling like itinerant workers forced to hop from writers room to writers room after four-to-eight weeks.

For companies, the macroeconomic environment marked by high inflation and rising interest rates also puts pressure on corporate leaders. Across the industry, there’s no wiggle room for investment and fliers on projects. USC’s Connor predicts that some of Hollywood’s biggest conglomerates will face hardball tactics from large private equity investors, such as the proxy fight from activist investor Nelson Peltz that Disney recently tamped down.

“The incentives for private equity stakeholders in so many of these companies have changed dramatically in the last 18 months because of the return of inflation and much higher interest rates,” Connor says. “There will be pushes from some of these investors to unload things.”

Issues like streaming viewership transparency, the future of AI in creative spaces and the length of time writers are guaranteed work on a show and what they’ll be paid are the central sticking points in the WGA stalemate. Behind closed doors, executives are looking at the same issues and preparing for more widespread changes before the dust settles. As writers reminisce about pilot season, executives and talent representatives also recognize the need for fundamental changes to course-correct the transition to streaming platforms.

But what that actually looks like is anyone’s guess. First, Hollywood has to figure out how to make real money on streaming platforms and how to shore up the money it now banks on linear channels. Both are far easier said than done. The avalanche of disruption in Hollywood has come largely from the entry of tech-rooted streamers that have never had a stake in the old ways of turning a profit on movies and TV shows.

“There’s got to be some things that get fixed first, because there’s such a dichotomy between the way these companies are making money,” one high-ranking TV studio exec says. “The legacy media companies have these broadcast and cable networks, the streamers aren’t quite encumbered, and even within the streaming world, they all make money in different ways, and these services mean something different to their ecosystems.”

Joe Otterson and Cynthia Littleton contributed to this report.

VIP+ Analysis: How Austerity Shapes Streamers’ Content M.O.

Best of Variety

'House of the Dragon': Every Character and What You Need to Know About the 'Game of Thrones' Prequel

25 Groundbreaking Female Directors: From Alice Guy to Chloé Zhao

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.