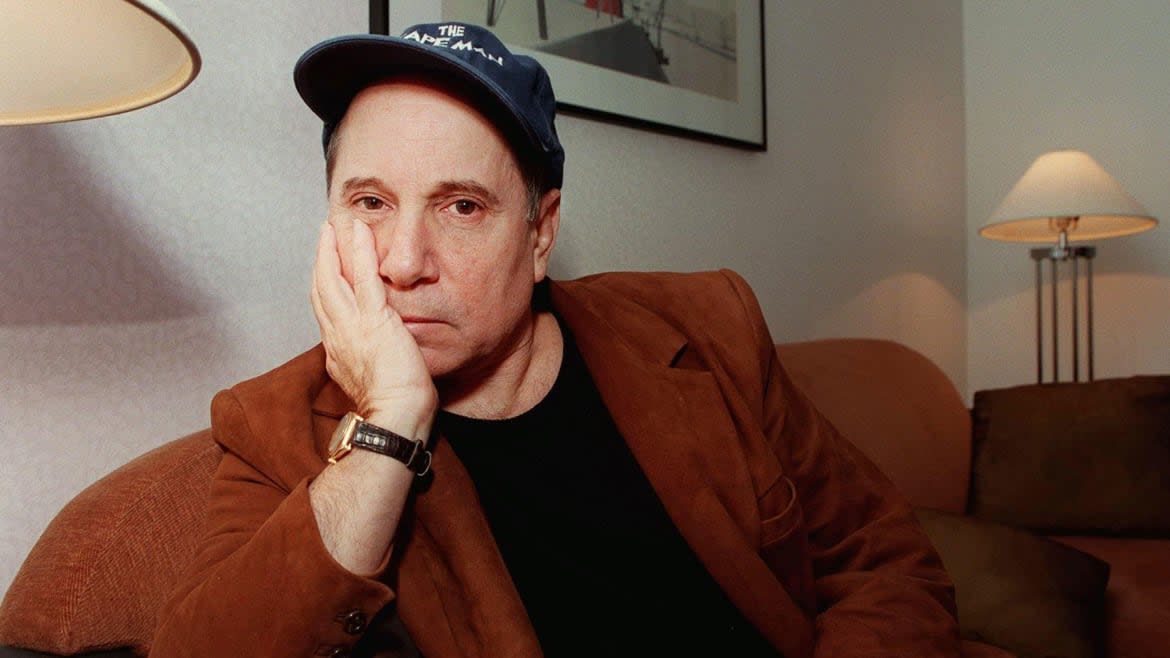

Paul Simon and the ‘Complicated’ Legacy of ‘The Capeman’ Musical

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Disney+ may be the current streaming hub for Swifties, but Paul Simon fans are in the middle of their own eras tour over on MGM+. The Amazon-owned streamer is hosting Alex Gibney’s two-part docuseries, In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon, which spans 3.5 hours and some seven decades in the life of the 82-year-old Queens-raised singer/songwriter. Dreams’ first half, which premiered March 17, covered Simon’s Tom & Jerry era up through the rise and fall of Simon & Garfunkel.

Part 2, premiering Sunday, March 24, continues Simon’s journey through the Still Crazy era, the One Trick Pony era, and the Graceland/Rhythm of the Saints era. When Gibney’s not rewinding to those musical touchstones, his film chronicles Simon’s present day Seven Psalms era, the slender seven-song record that debuted to mostly positive reviews last year.

Of course, serious Simon scholars know that 30 years and six studio albums separate Saints and Psalms, a long and varied creative period that’s entirely elided by In Restless Dreams. Gibney is well aware that he’s bypassing meaningful moments on the Simon timeline—and he’s also unapologetic about leaving out what might be some fans’ favorite later career album.

“I didn’t want to get trapped by, ‘Oh my god, we’ve got to put this [record] in,’” the prolific documentary filmmaker tells The Daily Beast. “That felt like a skipping-stone exercise and too encyclopedic. There’s a narrative to this film that had to be honored.”

And according to Gibney, that narrative wasn’t able to accommodate a detour that could be fodder for its own documentary: The Capeman era. In 1998, Simon took his talents to Broadway for a short-lived, highly divisive musical based on the story of Salvador Agron, the Nuyorican gang member who killed two teenagers on a Hell’s Kitchen playground. The New York tabloids and justice system seized on Agron’s crime—and identifying red-lined black satin cape—to transform the 16-year-old into a supervillain complete with a comic book-ready name: The Cape Man. Tried, convicted, and initially dispatched to death row, his sentence was later commuted to life in prison and further reduced after that, allowing for his release in 1979. Agron worked as a Bronx youth counselor until his death in 1986 at age 42.

“I never saw the show, but I’ve played the music from it a lot,” Gibney says, adding that he and Simon did have on-the-record discussions about The Capeman during the making of In Restless Dreams. “I don’t think it was properly appreciated at the time—well, I know it wasn’t because I went back and looked at the reviews!—but the music is exquisite.”

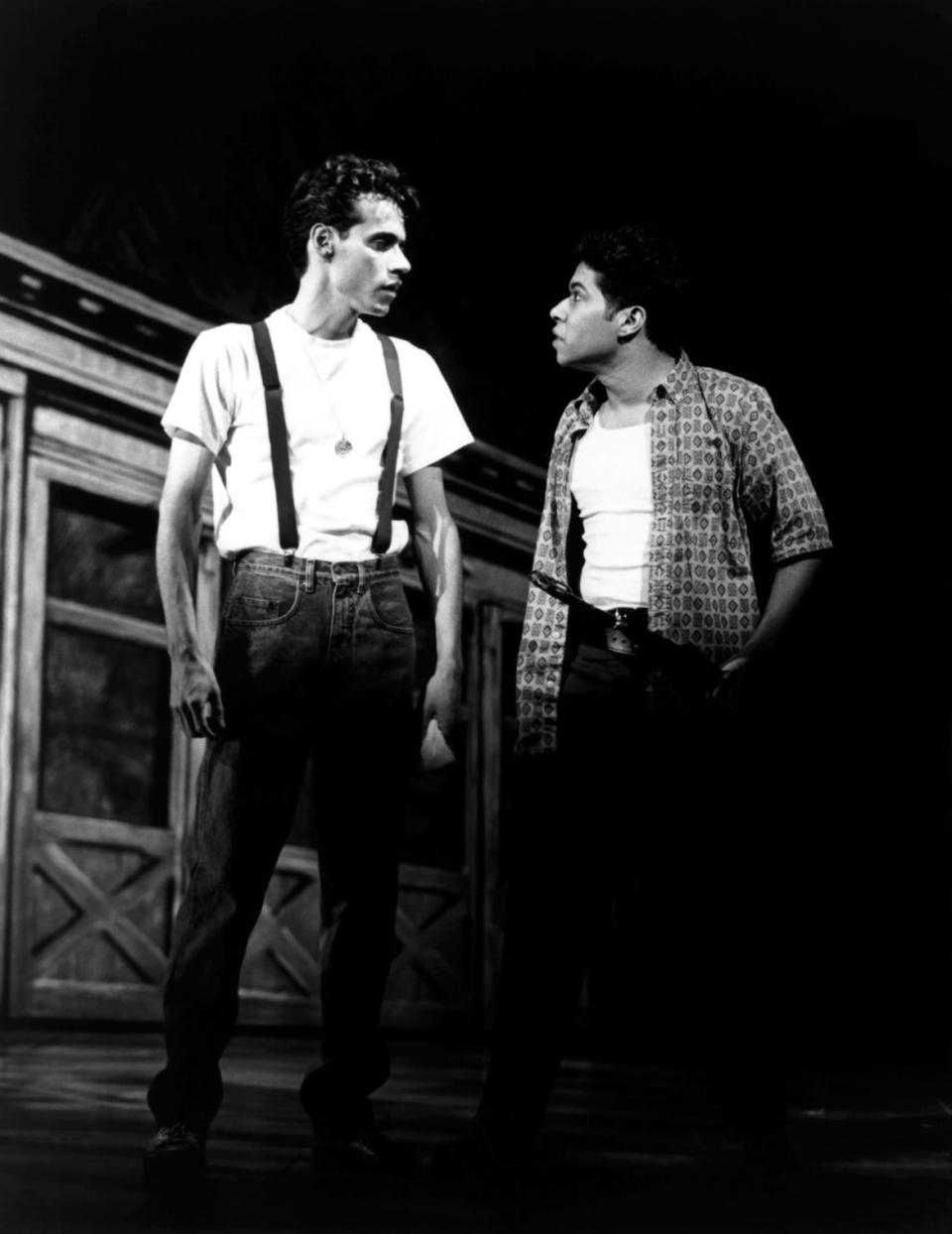

Ruben Blades in the 'The Capeman' at the Marquis Theater

Still, the director insists there was “no place” for those Capeman conversations in the finished film and doesn’t anticipate releasing a bonus track episode that covers the musical or the other albums—including Surprise, Simon’s acclaimed 2006 collaboration with Brian Eno—left out of In Restless Dreams. “The music is there, but there would have to be an organic story that would motivate another movie,” Gibney explains. “We weren’t thinking of this as a cinematic Wikipedia page where he had to get everything in.”

Born in late 1941, Simon was 17 when the Cape Man made headlines, and much of the singer’s impetus for revisiting the story in musical form involved re-connecting with the sounds of ’50s-era New York. “This is all about music,” he told The New York Times Magazine in a famously combative 1997 profile that preceded The Capeman’s January 1998 Broadway opening.

“The bonus for me is that here’s this coexisting culture that I didn’t pay attention to when I was a kid,” continued Simon, whose list of Capeman collaborators grew to include Caribbean author and poet, Derek Walcott, Nuyorican musical director Oscar Hernández and Latino singer/actors Rubén Blades and Marc Anthony, who played the older and younger Agron respectively. “I was always sort of vaguely aware of Latin music, because at that time my father was a bandleader, and he’d play at Roseland Ballroom, and the other band that played there was a Latin band. So these are the sounds that are just at the edge of my memory.”

Simon’s previous forays into other musical cultures—think of the electrifying South African guitar riffs that permeate Graceland and the percussive South American beats on Rhythm of the Saints—had brought him both acclaim and charges of cultural appropriation. (Those charges are re-litigated in the second half of In Restless Dreams, particularly Simon’s decision to travel to South Africa at the height of apartheid.)

But the controversy that swirled around The Capeman ahead of its release had less to do with the source of its songs than with the story Simon had chosen to re-tell. While the musician spoke about wanting to reinvent what a Broadway musical could be, many noted that The Capeman’s narrative remained centered around Puerto Rican gang violence, a tale as old as West Side Story.

That’s the concern that Columbia University professor Frances Negrón-Muntaner had when she saw The Capeman in previews. “I wanted to see the ways in which it was continuous and discontinuous with the treatment of Puerto Ricans in West Side Story,” says the scholar and filmmaker, who has written extensively about the 1957 musical theater chestnut. “There’d been so much work critiquing West Side Story, not only the stereotypes of the Puerto Ricans, but also the music itself, which has little to do with Puerto Rican music. I wanted to know if Paul Simon did what he said he wanted to do: bring authenticity to the true story of a Puerto Rican gang member.”

Like a significant portion of the audience at the time, Negrón-Muntaner exited the theater with mixed feelings. “I ultimately felt that The Capeman was not successful,” she surmises. “I appreciated that Simon had done his homework, but it was too dependent on storylines and types of characters that the Latino audience have become exhausted from. It would have taken something profoundly innovative to make Latinos be receptive to the same story all over again.”

Marc Anthony and Renoly Santiago in 'The Capeman'

Dr. Colleen Rua, who teaches Theatre Studies at the University of Florida, didn’t have the experience of seeing The Capeman in the theater, but came to the same conclusion when she watched the recording of the show housed at Lincoln Center’s Theatre on Film and Tape archive nearly a decade after it closed. “On the one hand, it provided representation for actors like Rubén Blades and Marc Anthony, but at the same time it was exacerbating these stereotypes that we had been seeing since West Side Story,” Rua says. “As with many things with Paul Simon, it’s complicated.”

The Capeman was also plagued by behind-the-scenes complications as reports of budget overruns and creative overhauls—with multiple directors coming and going from the show—made their way into the press. Those details were frequently referenced in the wave of negative reviews that followed the show’s premiere, with critics describing a lumbering three-hour production marred by disorienting time jumps and little dramatic flow between songs. “It’s like watching a mortally wounded animal,” Ben Brantley wrote in an unsparing New York Times pan.

After two months and fewer than 70 performances, the curtain came down for good on The Capeman on March 28, 1998. Simon appeared alongside the cast at the end of the final show, draped in the Puerto Rican flag. “If this is failure, what do you call a success?” he reportedly said as the audience leapt to their feet for a standing ovation. When the Tony nominations were announced in May, The Capeman received three nods, including Best Original Score, but left the ceremony empty-handed.

Paul Simon Tried to Stop Frank Sinatra From Covering His Iconic Song

For the record, Gibney says that the critical backlash to The Capeman did come up during his discussions with Simon. “He’s still immensely proud of some of the music and, of course, he’s still burned up over some of the stuff that was written about it,” the director says. “We did talk about it.”

Both Negrón-Muntaner and Rua agree with Gibney that the contemporaneous Capeman reviews from mainstream (and largely white) theater critics overlooked elements of the musical that did successfully depart from the West Side Story playbook. “When people walked into the theater, the curtain looked like the Puerto Rican flag, and that was huge for Puerto Rican audiences at the time,” Rua notes. “That design element made them go, ‘Okay this is something else. This is me.’”

Similarly, Negrón-Muntaner suggests that the significance of seeing Latino singers like Blades and Anthony belting on a Broadway stage wouldn’t necessarily have registered with critics. “They were mostly known to Spanish-speaking audiences, so their star power was at a different level,” she notes, while also adding that their presence alone wasn’t enough to overcome the musical’s larger flaws. “Those of us that were familiar with those performers didn’t feel that [their presence] did that much.”

Those who missed The Capeman during its short Broadway run had a long wait to hear the stars’ interpretations of Simon’s songs; an original cast album was recorded but sat on the shelf until a belated 2006 iTunes release. In the interim, Simon’s own 13-track compilation, Songs from The Capeman, was the only way to experience some of the show’s standout numbers, including “Bernadette,” which showcases the soaring doo-wop melodies of Simon’s childhood, and the majestically moody “Born in Puerto Rico.” Of course, the latter song is performed by someone who grew up closer to Corona Park than the Bronx’s barrios.

“It’s interesting, because he’s the composer sharing the composition he’s written,” Rua says of hearing Simon sing culturally specific lyrics like “I was born in Puerto Rico/We came here when I was a child” in the version of “Born in Puerto Rico” that’s on Songs from The Capeman. “But is he the musician/singer or is he the character? What is he representing? He’s an extraordinary musician, so one can really enjoy his singing the album as an album. But when it comes to storytelling, the songs come to life on the cast recording.”

Negrón-Muntaner is even more critical of Simon’s version of the song. “Simon shows respect [for Latino culture] but given the context, the fact that he sings ‘I was born in Puerto Rico’ is [both] tribute and theft,” she says after listening back to the Songs from The Capeman recording. “His pronunciation of the words ‘Puerto Rico’ is perhaps the most telltale sign of this instability. It is not only pronounced incorrectly, but also sounds overtly cautious. I was moved by the chorus’ sound, which made the question of inequity audible. The chorus feels like the legitimate narrator, yet it is in the background—anonymous and limited in its storytelling capacity.”

Simon notably didn’t take Songs from The Capeman on tour, although a concert version was reportedly discussed after the show’s closing. Those plans didn’t come to fruition until 2008, when the Brooklyn Academy of Music featured a Capeman-themed concert as part of a larger Paul Simon residency. Simon himself only sang one number at that six-night concert, the subdued travelogue “Trailways Bus,” while the rest of the songs were performed by a Latino cast. Two years later, a 90-minute Capeman production was staged at Central Park’s outdoor Delacorte Theater that seemed to hint at a potential revival.

It's likely not an accident that The Capeman’s reappearance followed the blockbuster success of In the Heights, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s 2008 Tony-winning musical that provided the long-awaited corrective to the depictions of Nuyorican life in West Side Story and The Capeman.

The Hamilton mastermind has discussed his own conflicted feelings about Simon’s musical over the years, telling The Los Angeles Times in 2008, “When I started writing In the Heights, the impulse was to try to fix Capeman.” (Following Walcott’s death in 2017, Miranda tweeted some of his favorite lyrics from the show in tribute.) Considering that Miranda provided newly translated Spanish-language lyrics to a 2009 revival of West Side Story, it’s tempting to imagine an alternate timeline where he also aided in “fixing” The Capeman, bringing it back to Broadway before moving on to Hamilton.

Nearly 15 years after the Delacorte staging, though, a Capeman revival remains out of sight. And Gibney sounds a skeptical note when asked about the possibility of Simon revisiting the musical again. “I don’t know—maybe,” he says. “In a way, he was ahead of his time; we’ve now seen Bruce Springsteen’s show [Springsteen on Broadway] and David Byrne’s American Utopia. Obviously, The Capeman isn’t biographical in the same way, but it’s kind of a precursor to some of the [musician-created] musicals that would come later.”

Rua’s personal preference would be for The Capeman to stay in the past. “It’s important as a contextual piece in understanding Latin representation on Broadway and even Paul Simon’s work—but is it really a story we need right now?” she says, noting that her students mainly respond to hearing a young Marc Anthony and observing some of the creative chances that Simon and Wolcott took with the structure. “There’s nothing that particularly stands out to them musically, and they’re acutely aware of the violent stereotype that’s being repeated.”

“But for all its shortcomings, I think The Capeman needed to be there in order for something like In the Heights to happen,” Rua continues. “It has a place as being a production that future musicals can be in conversation with.”

Meanwhile, Negrón-Muntaner has a pitch for the best way to revive The Capeman: Put Bad Bunny in it. “Today, you have globally recognized stars like Bad Bunny who don’t sing in English and are known by people who don’t speak Spanish. If the musical gets a reworking and casts talent that reaches that diversity of audiences that would generate a different kind of vibe.”

“But the bigger questions will remain the same,” she adds. “What can you say about this story and this music that we don’t already know? What makes it profound and important to now? It’s not impossible to bring The Capeman back—but it’ll take a lot of thought.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.