Paul McCartney Recalls How He Reconnected with John Lennon After the Beatles' Bitter Split

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

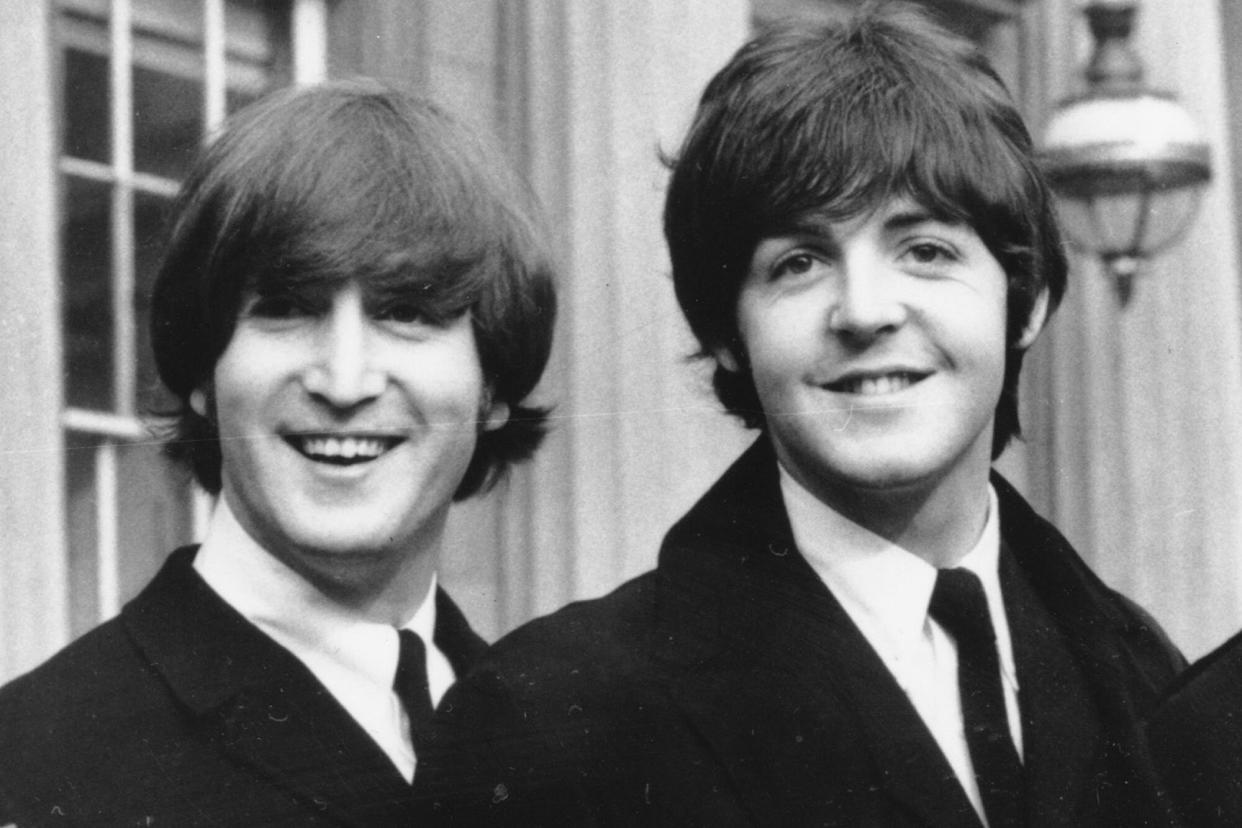

AP John Lennon and Paul McCartney

The Beatles, as they were quick to point out, in many ways resembled a family. Sure, there was a lot of love. But like all families, they could fight with the best of 'em. This was especially true in the aftermath of their split in the spring of 1970. Though they'd quietly agreed to go their separate ways the prior fall, it wasn't until the news went public that April that the mudslinging truly began.

Now, in his new book Lyrics: 1956 to the Present, Sir Paul McCartney is opening up about that troubled time in his relationship with John Lennon, his friend and musical soulmate. "When we broke up and everyone was now flailing around, John turned nasty," McCartney, 79, writes. "I don't really understand why. Maybe because we grew up in Liverpool, where it was always good to get in the first punch of a fight." Thankfully, he was able to make peace with Lennon before his tragic murder on Dec. 8, 1980.

Legal proceedings to dissolve the Beatles' partnership had begun almost exactly a decade earlier on Dec. 31, 1970. That same month, an embittered and emotionally raw Lennon released his first full-scale solo statement, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. Fresh off months of psychologically excruciating primal scream therapy, the album lay bare the psychological wounds that had been left to fester during the final days of the Beatles. The centerpiece of the record is the track "God" which ends with the climactic pronouncement "I don't believe in Beatles / I just believe in me" — a sentiment that bordered on blasphemy at the dawn of the '70s.

Shortly after the album hit shelves, Lennon sat down with Rolling Stone editor-in-chief Jann Wenner to give readers their first look at the beloved band's dirtiest laundry. He fired shot after shot at McCartney for his alleged bossiness in the studio, apparent disrespect of his new wife Yoko Ono, and supposedly unadventurous solo debut, 1970's McCartney.

McCartney was not amused. "John was firing missiles at me with his songs, and one or two of them were quite cruel. I don't know what he hoped to gain, other than punching me in the face. The whole thing really annoyed me," he recalled in Lyrics. "John would say things like, 'It was rubbish. The Beatles were crap.' Also, 'I don't believe in The Beatles, I don't believe in Jesus, I don't believe in God.' Those were quite hurtful barbs to be flinging around and I was the person they were being flung at, and it hurt. So, I'm having to read all this stuff, and on the one hand I'm thinking, 'Oh f— off, you f—ing idiot,' but on the other hand I'm thinking, 'Why would you say that? Are you annoyed at me or are you jealous or what?' And thinking back 50 years later, I still wonder how he must have felt."

In retrospect, he blames Lennon's combative nature on a string of devastating losses early in life. "He'd say, 'My dad left home when I was 3, and my mother got run over and killed by an off-duty policeman outside the house, and my Uncle George died. Yeah, I'm bitter,'" McCartney writes. "John always had a lot of that bluster, though. It was his shield against life. We'd have an argument about something and he'd say something particularly caustic; then I'd be a bit wounded, and he'd pull down his glasses and peer at me and say, 'It's only me, Paul.' That was John. 'It's only me.' Oh, alright, you've just gone and blustered and that was somebody else, was it It was his shield talking."

McCartney's response to Lennon's vitriolic outbursts was, characteristically, more subtle. "I decided to turn my missiles on him too, but I'm not really that kind of writer, so it was quite veiled," he says. "It was the 1970s equivalent of what we might today call a 'diss track.' Songs like this, where you're calling someone out on their behavior, are quite commonplace now, but back then it was a fairly new 'genre.'"

On his second solo disc, 1971's Ram, he included a jab at Lennon on the opener, "Too Many People," scoffing at the ex-Teddy Boy's exhortations for world peace chastising his bandmate for taking "his lucky break" and breaking it in two. "[That] was me saying basically, 'You've made this break, so good luck with it.' But it was pretty mild...It was all a bit weird and a bit nasty, and I was basically saying, 'Let's be sensible. We had a lot going for us in the Beatles, and what actually split us up is the business stuff, and that's pretty pathetic really, so let's try and be peaceful. Let's maybe give peace a chance.'"

RELATED: Paul McCartney Reflects on How His Late Mother Became His Greatest Muse

But, at least in the short term, peace was not forthcoming. Lennon's response to McCartney's comparatively soft musical dig was to go nuclear with "How Do You Sleep," a diss track so venomous and overt that it borders on obscene. Even more hurtful to McCartney, the slide guitar on the track was played by none other than George Harrison. In film footage of the session, later released as part of the Imagine documentary, Lennon can be seen huddled with Harrison and Ono, gleefully giggling like conspiratorial children as they trash their former bandmate. "The sound you make is muzak to my ears/You must have learned something in all those years," Lennon sings, before taking aim at McCartney's most famous song: "The only thing you done was yesterday/And since you're gone you're just another day."

Though he didn't punch back, McCartney was undoubtedly crushed by the words. "I had to work very hard not to take it too seriously, but at the back of my mind I was thinking: 'Wait a minute, All I ever did was "Yesterday"? I suppose that's a funny pun, but all I ever did was "Yesterday," "Let It Be," "The Long and Winding Road," "Eleanor Rigby," "Lady Madonna"….f— you, John.'"

When McCartney did respond publicly, on 1971's Wild Life, it was with an olive branch. His first venture with new band Wings included the mournful "Dear Friend," an open letter to Lennon that matched "How Do You Sleep" for candor. Built around a haunting solo piano figure, a grief-stricken McCartney sounds lost as he wonders if this was "really the borderline" of their friendship. "I just felt sad about the breakdown in our friendship, and this song kind of came flowing out. 'Dear friend, what's the time?/ Is this really the borderline?' Are we splitting up. Is this 'you go your way; I'll go mine?" he writes.

Half a century later, the line "Are you afraid / or is it true" strikes him as particularly poignant. "Meaning, 'Why is this argument going on? Is it because you're afraid of something? Are you afraid of the split-up? Are you afraid of my doing something without you? Are you afraid of the consequences of your actions?' And the little rhyme, 'Or is it true?' Are all these hurtful allegations true? This song came out in that kind of mood. It could have been called 'What the F—, Man?' but I'm not sure we could have gotten away with that then."

Lennon kept his response to the song to himself, but the public sparring soon ceased. Relations began to thaw and the channels of communication began to open, though contractual topics and legal matters were best to avoid. "At first, after the breakup of the Beatles, we had no contact, but there were various things we needed to talk about," says McCartney. "Our relationship was a bit fraught sometimes because we were discussing business, and we would sometimes insult each other on the phone. But gradually we got past that, and if I was in New York I would ring up and say, 'Do you fancy a cup of tea?'"

McCartney noticed a shift in his friend following the birth of his son Sean in 1975. "We had even more in common, and we'd often talk about being parents."

Lennon effectively retired from music for the next five years, devoting his life to Sean's care. Fittingly, it was his old collaborator who inspired him to pick up a guitar once again. Lennon heard McCartney's electro-tinged 1980 single "Coming Up," an unconventional track that seemed to predict the impending onslaught of New Wave artists. "John described 'Coming Up' somewhere as 'a good piece of work.' He'd been lying around not doing much, and it sort of shocked him out of inertia. So it was nice to hear that it had struck a chord with him." Lennon's so-called "comeback" album, Double Fantasy, featured some of the same New Wave sensibilities. He was returning home from a session for a follow-up record on the night of Dec. 8 when an assassin fired four shots into his back.

For McCartney, the timing was particularly cruel, as he and Lennon had finally started to rekindle the warmth that had been absent between them for so long. Yet at the same time, this also made it easier to say goodbye. "I was very glad of how we got along in those last few years, that I had some really good times with him before he was murdered," he writes. "Without question, it would have been the worst thing in the world for me, had he been killed, when we still had a bad relationship. I would've thought, 'Oh, I should've, I should've, I should've…' It would have been a big guilt trip for me. But luckily, our last meeting was very friendly. We talked about how to bake bread."

It also marked a turning point in his notoriously tempestuous relationship with Ono, who was now thrust into the unenviable role of rock's most famous widow. "Of course, from then on really, I was very sympathetic to Yoko. I'd lost my friend, but she'd lost her husband and the father of her child."

McCartney paid tribute to his friend in the best way he knew how: with a song. Written during sessions for 1982's Tug of War, "Here Today" is a delicate acoustic ballad in which McCartney directly addresses his fallen friend by reliving shared memories.

"I was remembering things about our relationship and about the million things we'd done together, from just being in each other's front parlors or bedrooms to walking on the street together or hitchhiking — long journeys together which had nothing to do with the Beatles." He nods to Lennon's trademark bluff with the opening verse:

If I said I really knew you well

If you were here today?

Well knowing you

What would your answer be

You'd probably laugh and say that we were world's apart

If you were here today

"I'm playing to the more cynical side of John," says McCartney in Lyrics, "but I don't think it's true that we were so distant." As the song continues, he sets aside all pretenses with "What about the night we cried/Because there wasn't any reason left to keep it all inside." The lines recall the moment that they both let their guard down while on the road in 1964, during the height of the mania that their music had created. "That was in Key West, on our first major tour of the US, when there was a hurricane coming in and we couldn't play a show in Jacksonville. We had to lie low for a couple of days, and we were in our little Key West motel room, and we got very drunk and cried about how we loved each other."

It was a sentiment that didn't come easy to two guys from Northern England. "I don't think it's as true now as it was back in the 1950s and '60s, but certainly when we were growing up you'd have to be gay for a man to say that to another man, so that blinkered attitude bred a little bit of cynicism," McCartney writes today. "If you were talking about anything soppy, someone would have to make a joke of it, just to ease the embarrassment in the room. But there's a longing in the lines, 'If you were here today,' and 'I am holding back the tears no more,' because it was very emotional writing this song. I was just sitting there in that bare room, thinking of John and realizing I'd lost him. And it was a powerful loss, so to have a conversation with him in a song was some form of solace. Somehow I was with him again." It provided the opportunity to say everything that had gone unsaid.

And if I say I really loved you

And was glad you came along

Then you were here today

For you were in my song

"'And if I say/I really loved you' — There it is, I've said it," McCartney writes. "Which I would never have said to him."

More than four decades after Lennon's death, McCartney still feels the presence of his collaborator when he sits down to compose. "As I continue to write my own songs, I'm still very conscious that I don't have him around, but I still have him whispering in my ear after all these years. I'm often second-guessing what John would have thought — 'This is too soppy' — or what he would have said different, so I sometimes change it. But that's what being a songwriter is about; you have to be able to look over your own shoulder...Now that John is gone, I can't sit around sighing for the old days. I can't sit around wishing he was still here. Not only can I not replace him, but I don't need to, in some profound sense."