How Patrick Page Found Himself in Shakespeare’s Villains

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Patrick Page knows of what he speaks. The Tony-nominated and Grammy-winning star of Hadestown—and, as the Green Goblin, venerable survivor of Spiderman: Turn Off the Dark—has played many of Shakespeare’s villains.

In his 85-minute one-man play, All the Devils Are Here: How Shakespeare Invented the Villain (DR2 Theatre, booking to Jan 7, 2024), Page wants to analyze not just what makes the villains tick, but how and why Shakespeare created such lasting characters, and character types for villains that have followed for centuries since on stage and screen, and why we love watching them. It is a simple stage, with a dramatic swoop of theater curtain, and sundry objects; Stacey Derosier’s lighting is an evocative mood-setter. Excellent dry ice machine, too.

The NYC Party Where You Debate Shakespeare’s Identity All Night

Page intersperses his analysis and history with enacted monologues from the plays, beginning with Lady Macbeth’s “Come, you spirits/Make thick my blood” speech from Macbeth, which sets the tone. In terms of texts chosen, this is an unapologetic greatest hits exercise. The pleasure of it is less in revelation or alighting on a new or radical theory of Shakespearean villainy, but in Page’s expert and smooth recitations of text, and his concise analysis.

Page says that today, in the world so ideologically polarized, many believe their enemies to be evil. “Shakespeare saw it coming,” he contends. “He investigated evil more deeply and more personally than virtually anyone before or since. In fact, for all intents and purposes, Shakespeare invented the character we now call ‘The Villain.’”

The Bard’s 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and poems are, for Page, “one great life-sustaining creation,” and he traces Shakespeare’s perception of villainy from the personified sin of the figure of the Vice in Morality Plays to the first villain he created, Richard, Duke of Gloucester in Henry VI, Part 3—notable because his physical deformity was written as a manifestation of his villainy, a horrible stereotype which has long persisted.

Yet in the writing, Page says, “Shakespeare was discovering that, despite ourselves, we are often seduced and titillated by characters who stand outside the bounds of everyday morality.” He contrasts Elizabethan Antisemitism with how Shakespeare imagined Shylock in The Merchant of Venice—a villain, for sure Page says, but “whose motivation is so clear, whose psychology is so complex, and whose language is so rich that he changes the way we experience villainy itself. Shakespeare forces us to ask: if we had been treated as Shylock was treated, might we find the same thirst for vengeance in ourselves? Could we be villains?”

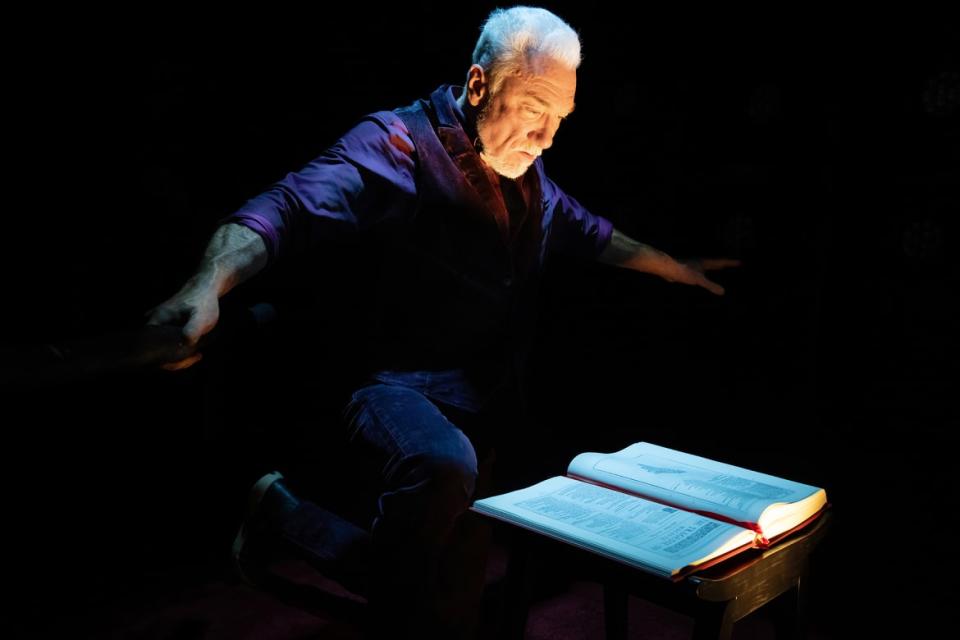

Patrick Page in 'All the Devils Are Here.'

Then it’s on to Malvolio in Twelfth Night and Claudius in Hamlet (“What if this cursed hand/Were thicker than itself with brother's blood,/Is there not rain enough in the sweet heavens/To wash it white as snow?”). Hamlet, Page notes, vowed to “catch the conscience of the King,” and Shakespeare made his play “immeasurably richer by making sure that both his hero and his villain had a profound sense of right and wrong.”

In Iago in Othello, who Page has played, he locates a human vehicle for psychopathy, opening Page’s “eyes to the reality of the evil hidden in plain sight among us.” Then on to Edmund in King Lear, and Macbeth’s tragedy—for Page, this “is not that he is evil—his tragedy is that he chooses evil.”

After Macbeth, Page tells us, “Shakespeare never went to that dark place again. The plays that follow are mostly Romances—fantastic tales that begin in crisis but end in harmony and reconciliation.” He finishes his talk as Prospero, breaking his staff and eternally, quotably bidding farewell to his powers. “As dreams are made on, and our little life/Is rounded with a sleep.”

It has been a brisk, and pleasant analysis, but it feels in some ways too slight, rushed, and not investigative enough—like a decorous, beautifully modulated TED talk. Page alludes to the power of playing a villain, and what it has meant to him, and how intense it has been for him at times. But we hear no more of this. How has playing villains, Shakespearean and not, affected him, or changed anything of him? And what of women? Apart from Lady Macbeth’s opening salvo, we hear nothing of Shakespeare’s villainous women—we need more of Lady M, and others like Goneril. What of revelatory text spoken by villains that may be illuminating or complicating that isn’t so well-known? But Page is a charming, consummate raconteur, and this is still an inviting feast—it’s to his credit he leaves us wanting way more.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.