Patricia Kennealy-Morrison, rock journalist, author and partner of Jim Morrison, dies at 75

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Patricia Kennealy-Morrison, who died on July 21 at age 75, was a prolific, life-long writer who in the late 1960s helped pave the way for women in music journalism and later penned popular science fantasy novels and mysteries.

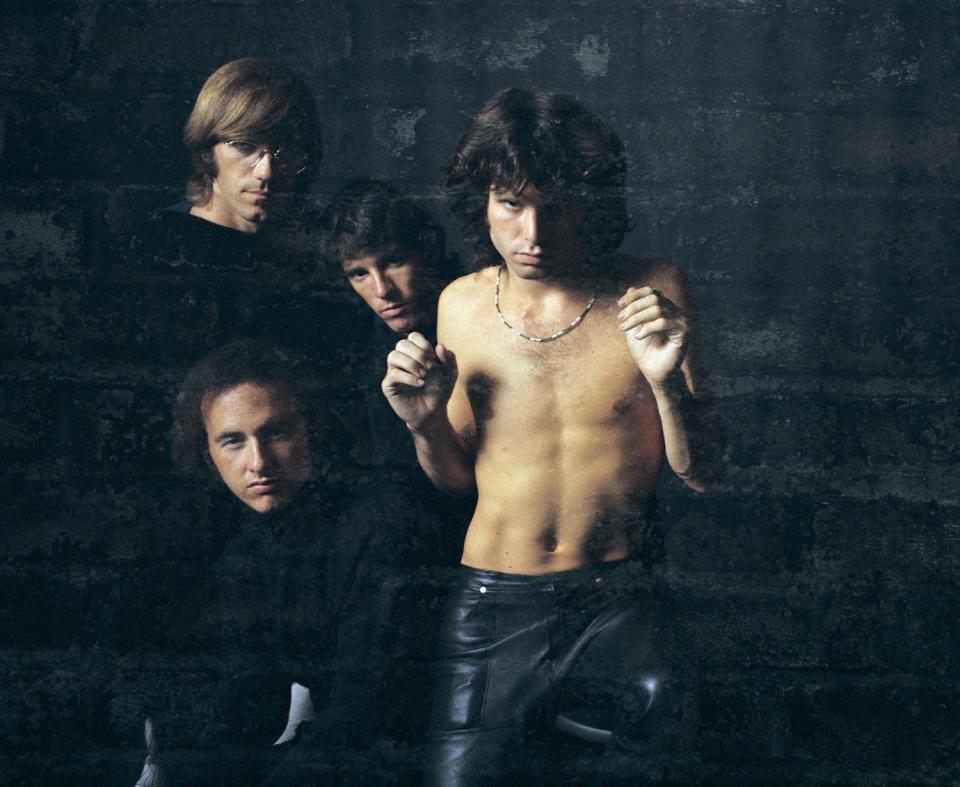

She was a writer of fantasy who lived out a rock ’n’ roll dream of sorts. Her place in music history was sealed the day she interviewed Doors singer Jim Morrison in 1969. A romance followed, and Kennealy-Morrison was immortalized in Oliver Stone’s 1991 movie “The Doors” as the woman to whom the singer committed in a Celtic hand-fasting ceremony. The writer appeared in the movie as the priestess performing the pagan wedding.

It is sadly ironic that Kennealy-Morrison is most famous for her rock-star liaison, since she was a talented and strong-voiced critic who was acutely aware of the paucity of opportunities offered to women in music. “For all its self hype to the contrary, rock is just another dismal male chauvinist trip, with one important difference: it’s got the power and the looseness with which to change itself,” she wrote in 1970 in Jazz & Pop, the magazine she edited.

“Patricia was as fierce as they come,” said Ellen Sander, a writer who was one of Kennealy-Morrison’s peers in the early rock press, in an email to The Times. “She was in that first wave of rock journalists that penetrated print media with features and news that nourished a voracious but widely unrecognized readership at the time. She evolved from what she considered to be a small-minded coterie of rock music journalists to become a popular genre fiction author and produced an astonishing volume of works.”

Patricia Kennely was born March 4, 1946, in Brooklyn, N.Y. (she later changed the spelling of her last name to match how it is pronounced). She got her bachelor's degree from Harpur College (now State University of New York at Binghamton) in 1967. She settled into an East Village apartment shortly after moving to Manhattan “and basically never came back,” recalls her brother Kevin Kennely. The writer’s body was found in her bed in that apartment in late July. The cause of death was complications from heart disease.

Kennealy-Morrison started her adult life in a time and place famous for its culture, politics and soundtrack. She lived a few blocks from the Fillmore East, Bill Graham’s club where rock stars honed their legends. “… in those days music really could tear down walls, really could create a shared sense of community and context,” she wrote in her 1992 memoir, "Strange Days: My Life With and Without Jim Morrison."

The field of rock criticism was just being invented, and after quickly working her way up the masthead to become editor of Jazz & Pop, she emerged as one of the few women documenting the scene. She wrote with a sharp wit and a healthy mix of skepticism and romance about the towering figures of that time: Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, etc.

Kennealy-Morrison was acutely aware of the novelty of her position as a female music journalist. “Most of the women in rock journalism were little more than glorified gossipers, whether through circumstance or inclination. There were not all that many women who were given, or who seized for themselves, the freedom to write like men, like writers …” she wrote in "Strange Days."

And yet she herself was vulnerable to the seductions of one of the most famous, and infamous, musicians of that time. Jim Morrison was a poet and sex symbol, the self-styled “Lizard King” who had a reputation for volatility (he also had a longtime girlfriend, Pamela Courson). In "Strange Days," Kennealy-Morrison wrote that when they first met, sparks literally flew from static electricity when they shook hands. She took it as a sign: “I know already that this is so different, that he is different, that I am different with him. This is no editor and interview subject; nor is it star and starstruck groupie, as it would have been with those little girls downstairs. This is something else, something more, something realer…”

As a believer in Celtic witchcraft, for Patricia, the handfasting ceremony with Morrison was spiritually binding. They were never legally married and many Doors fans contest Kennealy’s assertions they were husband and wife. She maintained they were still in a relationship when he died of an overdose in 1971. In 1979 she changed her name to Kennealy-Morrison. Years later she named her publishing company and website Lizard Queen.

“At Jazz & Pop she was one of the few females working in a man's world and her relationship with Jim Morrison and over-protective Doors fans sometimes eclipsed her own body of work, especially on the internet,” says Carla DeSantis Black, who met Kennealy-Morrison after publishing an interview with her in her Rockrgrl magazine in 1996. “But she was a prolific fantasy writer as well as a music writer.”

Kennealy-Morrison wrote about her frustrations interviewing rock stars in 1970. “I do tire of flailing away at that ol’ male chauvinist hydra, but I tire even more of going out to do an interview and being genteelly condescended to as not much more than a particularly well-connected groupie, and then, sometime during the interview, having to watch the interviewee male drop his drink at a perfectly ordinary remark as to, oh, the influence of eighteenth-century Irish-Scottish broadside ballads in his work, or John Cage, or Django Reinhardt, or even nonmusical things like the auteur theory of filmmaking, or just about anything having more intellectual content than ‘What’s your favorite color?.’”

After Morrison’s death, Kennealy-Morrison worked for RCA and Columbia Records, creating successful advertising campaigns. She began writing science fantasy in the 1980s. Her popular Keltiad series included a hero, Morric Douglas, modeled after Jim Morrison. She also wrote a series of rock ’n’ roll mystery books. She published under various names, including Patricia Kennely and Patricia Morrison.

Kennealy-Morrison was proud and protective of her reputation. Black says they met after the author wrote to “eviscerate” her over the introduction the editor had written for the Rockrgrl article. They subsequently became friends. “Low maintenance she was not,” Black says. “But she had a very kind heart and if you were fortunate enough to be on the list of people she trusted you could do no wrong. She appreciated other big personalities.”

Kennealy-Morrison is survived by her brothers Timothy and Kevin Kennely.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.