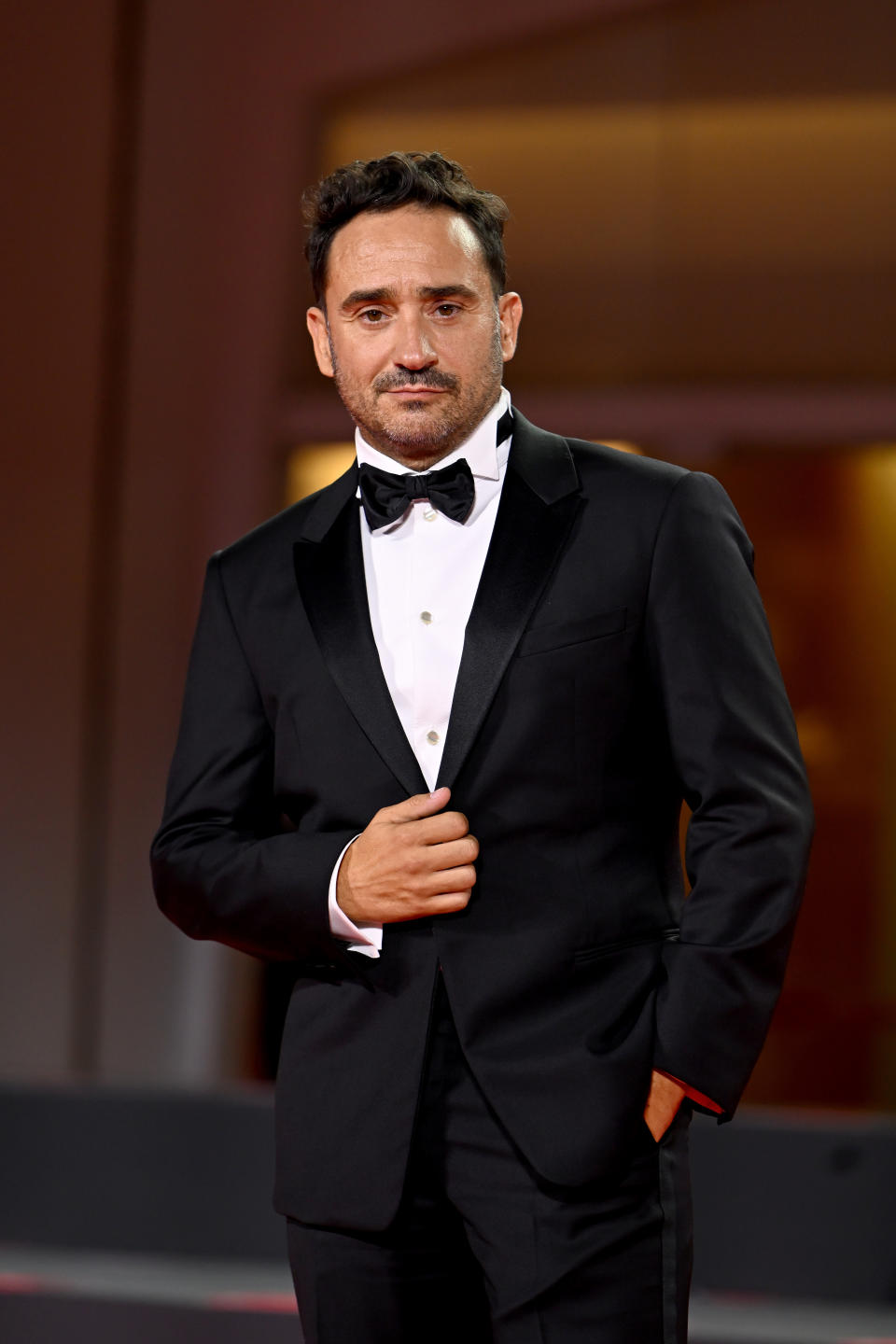

The Partnership: J.A. Bayona & Author Pablo Vierci Tell The Real Story Behind ‘Society Of The Snow’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1972, a small passenger plane crashed into a mountain in the Andes, its tail and wings ripping off in the impact. When the fuselage came to rest on the snow, it contained 33 survivors, among them the young members of a Uruguayan rugby team. Over an unimaginable 72 days, they would contend with starvation, exposure, hypothermia and two avalanches, until only 16 remained alive. Ultimately, they were forced to make an agonizing choice: consume the bodies of the dead or die themselves. J.A. Bayona’s film Society of the Snow, based on Pablo Vierci’s book of the same name, takes a fresh look at the story, giving voice to both the dead and the living. Here, the Spanish filmmaker and the Uruguayan author discuss how they collaborated to tell a vital story of human will and sacrifice that would honor the real experience of the survivors and their dear departed friends.

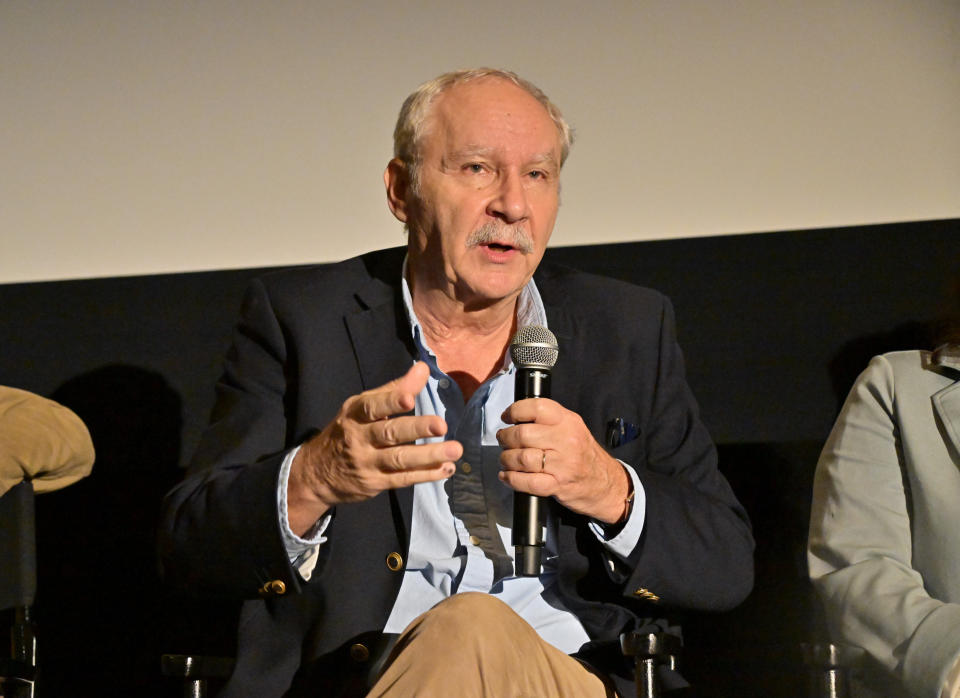

DEADLINE: Pablo, how precious and important was this story to you when you came to write it?

More from Deadline

‘Cassandro’ Star Gael García Bernal Pins Down The Exotic Appeal Of A Pioneering Gay Mexican Luchador

PABLO VIERCI: Well, I went to school with the survivors and with the deceased people, and all memories of my childhood are with them. I was 22 in 1972, and something like this, a catastrophe like this, everything changed, because at 22 years old you think everybody at that age is immortal. A plane with all your friends disappeared, there was 72 days of mystery, where my friends and I, who were in Uruguay, who didn’t go in the plane, we thought that they were not alive. So, when they appeared on the 23rd of December 1972, and when we knew the list, the 16 alive, and 29 deceased, everything broke in our heads, and in my mind, and in my emotions. When they came back, [survivor] Nando Parrado, he was my classmate, he asked me to help him with his writing. I had a commitment with the survivors and fundamentally with the deceased, because there were too [few] people who knew them for 20 years, and nobody who wrote about them.

DEADLINE: J.A., you bought the rights around the end of shooting The Impossible. I remember watching Alive, which came out in 1993, and I read the book it was based on, by Piers Paul Read. Did you? Why this story?

J.A. BAYONA: The story is very popular in the Spanish-speaking world. We all know Alive. I was very little, so I only remember when I was a kid that the book was everywhere, every house that you visited. I knew about this idea of cannibalism, that was everywhere, and I was very impressed about the pictures. And I grew up watching interviews on television with the survivors. But my surprise was when I read Pablo Vierci’s book, while researching for The Impossible. I was in shock, because I was so moved by a story that I thought I knew. And I think it’s because Pablo Vierci’s book has a spiritual tone that makes it so special, so moving. The book was published because 35 years after the accident not even the survivors recognized themselves in the tale. The tale was very focused on cannibalism, the tale was focused on heroism, they didn’t recognize what they went through with those words. So, they sat down together again and wrote a different book where you can feel the weight of time, you can feel the questions that are still not answered. And the big challenge was, how can I get this spiritual book into a script? Because scripts are about dialogue and action, and I was interested in the inner life of the characters.

DEADLINE: At what point did you decide on using a voiceover narration via Numa Turcatti, who ultimately passed away before the rescue? We hear his diary entries after the crash.

BAYONA: By creating this kind of fantasy where you make the narrator one of the dead, and you use the voiceover of one of the dead, you create a fantasy that somehow has this spiritual take that Pablo Vierci’s book has. It becomes something more metaphysical; it becomes something more about the story on a human level, a philosophical level. So, it made sense to me, because when you think about what the story’s about in its essence, this is a story of Numa, who is one of the kids that faces the primal fears that we all have: fear of death, to be alone, to not be loved, hunger. Basically, he needs to forget the civilization he’s coming from, and adapt to the mountain to discover himself, and to process the shadow that we all have inside. And by doing so he understands what is to me the essence of the story, that you and I are the same thing. There is a moment when someone says to Roberto Canessa, “You have the best legs, you need to walk for us.” That’s the idea I’m talking about. The ones that were dying, saying, “Use the only thing that I have left, my body.”

VIERCI: You can have a script with the words and the dialogue and with the action, but it was an exploration, because we are [exploring] in between life and death. After the film was screened for the families of the dead, and the survivors here in Uruguay, with J.A. and [producer] Belén Atienza, and [producer] Sandra Hermida, J.A. and I spoke with the families, and the brothers and sisters of the deceased. They understand now what happened, 51 years later.

DEADLINE: With Numa, because it’s his voice narrating, you don’t expect him to pass away. Was that a story you put together from what the other survivors told you? Or was it actual diary that Numa wrote?

BAYONA: No, we had more than 50 hours of conversations with the survivors, and then we met Numa’s family and Numa’s friends. I think I had a good idea of who Numa was. I think that he’s still a mystery nowadays, some of the decisions he made on the mountain. Numa never saved anything for himself, he was all the time for the other ones, and he didn’t make it. Which raises a question, what is the sense in that? What’s the meaning of that? It’s totally the opposite message of the normal stories that you see in Hollywood, that the good, the best ones survive. But he’s remembered as the best one, and he died 12 days before the rescue. So, I really like that question there, because that’s the big question in life, in art. What is the meaning of life?

VIERCI: What J.A. is saying is crucial, because we spoke with the families of the deceased and the survivors, and they told us that in this story there are survivors because the dead gave their bodies so that others could live. It’s unique. In other situations, the living don’t need the dead to survive. But here there was an agreement, where the dead agreed that the living could use their bodies to carry on if they died. There is a document written by one of the passengers, Gustavo Nicolich. He died in the avalanche, on the 29th of October. He wrote, “If you need my body, I will be happy to give it to you.”

So, it’s a unique situation, where there are survivors because there are dead guys. It’s very strange. So, we can go deeper into the spiritual, or into the philosophical, or into the ethical issues, because it’s unique.

DEADLINE: Tell me about the decision to make this a Spanish language film. It’s culturally so important but I also imagine it made getting financing harder.

BAYONA: Yeah, it made the financing impossible. So, it took us 10 years, until finally Netflix showed up and gave us a chance to shoot the film the way we wanted.

VIERCI: The Spanish, I think, is something new to audiences today, in 2023. More and more people want the authentic, they want the truth, and the truth here must be in Spanish as it was spoken in Uruguay in the ’70s.

BAYONA: We were super-perfectionist in trying to get the Spanish from the ’70s. And some of the actors were from Argentina, and Pablo here was on set correcting them. Sometimes they were using this tone from Argentina, or expressions that are modern, and we would replace them, because we really wanted to capture the music of the sound of the Spanish in that moment.

VIERCI: I think that 10 years ago you could have a Russian film speaking in English, but I don’t know if today the audience wants to see the French speaking Spanish.

BAYONA: You know, I love Pablo’s book, and I really wanted to capture the scope of the book, it’s a giant book. Not only about the adventure but about all the levels that the story has on the philosophical, the spiritual, the human side. So, to me it was more like we’re going to try to get inside the story, we’re going to try to tell the whole story, we’re going to go hand-in-hand with the actors, and we’re going to go through the same journey as close as possible.

So, we shot it chronologically, in real locations, the same locations. You cannot tell the story without understanding the context of what is to be in the Andes. The first thing I did when we got the green light, was to go to the same place where the plane crashed, and spend a couple of nights there at the same time of the year that they were there, which is insane, because it takes you three days to get there, only to get used to the altitude. It’s a place where you sleep in a camp, and when you wake up in the morning, your bottle of water is a piece of ice. And when you’re there, you see the size of the mountains, you hear the silence, the only thing that you can hear there is yourself, then you understand the story.

So, we had to tell that story to the audience, and we did it with the actors, we did it with the journey that they went through. We prepared them, we gave them the book, we gave them the contact with the survivors, or the families of the deceased, and they started to contact throughout the shoot. And they are still in contact with the survivors now, the actors, still talking to them. So, they had all the information. And then we gave them the chance of going through the same experience. We shot in the snow, in very difficult conditions, going through the hunger by doing a strict diet. Some of the actors lost more than 20 kilos.

DEADLINE: 20 kilos? Wow.

BAYONA: Yeah. So, we were going through the same things they went through, of course with a distance. You can tell how close the journey was when you see an actor dying on the story and leaving the set. Because you can tell how strong the connection was between all of them, you can see the despair in their faces, like seeing a friend, because at the moment they were already friends, leaving the film. But we did basically a very, very massive film, going hand-by-hand with the actors, trying to make everybody understand what they went through, and by doing so they will understand what they did.

Which basically is what Pablo was telling you. It was incredible to see the movie with the families of the deceased, and some of them after 51 years, understood how bad it was for the other ones, and understood why they did what they did.

It was super shocking to me, seeing one of the brothers of the dead hugging Gustavo Zerbino, one of the survivors, and telling him, “I don’t know if I cried for my brother, or for you.”

DEADLINE: Pablo, how much of the shoot did you personally experience?

VIERCI: I had been with J.A. and Belén and Sandra since 2016, so I knew a lot. I accompanied the shooting, and it seemed for me that I was behind J.A. Bayona and I was behind Leonardo da Vinci. It’s something very strange for me, because every day began with something very, very rough. We suffered a lot, but at the end of the day we thought that we were touching the ceiling, we were in the best place in the world.

DEADLINE: It must have felt very emotionally heavy just to be there, at the crash site. Tell me about that.

BAYONA: Yes, we went there three times. We couldn’t shoot much there because it’s not a safe place. With global warming there’s a lot less snow, so the amount of time you have snow in there every year is less and less. The first time we went there actually there was not much snow, so we shot the background, and we had a very good idea of what it was to be there, I can tell you. It was a very intense experience to be there, as you said, not only physically, but also emotionally.

There are still some remains there from the plane. There is a grave full of objects. It’s unbelievable, people go there to leave objects in the summer. But we went there in the winter, we could barely see the grave because it was under the snow.

And then the rest of the shoot was in a ski resort in Spain, but it was pretty high. There were moments that some of the people of the crew had to go back to the base camp, because of the altitude. I don’t know how many is in feet, but it was 2500 meters. That’s pretty high.

This is where we placed the fuselage, and we shot most of the scenes there. We had two other planes, one was in a big soundstage that we built in the ski resort, surrounded by LED panels, and then we had a third plane that was in the middle of an olive tree plantation. It was very bizarre, because we made a huge platform of snow, and in the middle there was this plane.

DEADLINE: How did you cast these unknown actors?

BAYONA: I had sat down with the survivors, so I had a very good idea of who they were. So, I was also interested in getting people that look alike somehow, but that was not the priority, the priority was always to match the idea I had of them, the way they behaved in the mountains. We auditioned for six months, during the pandemic, so most of them were self-takes that I watched, and then I started to meet them via Zoom. The other day the casting director said, “You saw 2,000 takes.”

DEADLINE: Pablo, were you in involved with that process?

VIERCI: Yes, I was, when they did it in Uruguay.

BAYONA: When we went to meeting them in person, then we went to Uruguay. I went to Montevideo, Pablo was there, and most of them had to come from Argentina. During the pandemic for the regulations that were establishing in Argentina, they had to stay one week doing quarantine before doing the auditions, and one week to go back to Argentina. So, imagine what it is to have 30 guys between 18 and 26 years old, in a hotel for two weeks alone. Of course, immediately they were best friends. I’m still friends with some of the people who didn’t do the film.

VIERCI: Because I knew them, the survivors and the deceased, I was right behind J.A., not in the physical [sense] but the psychological. The decisions came from J.A., but I was whispering in his ear.

BAYONA: There were two ideas behind the fact that we didn’t want to have famous faces. One is that we didn’t want to have protagonists, like a famous face in the middle of the other ones. And not having popular faces would add realism, to make it look more like a documentary.

DEADLINE: Pablo, how did you feel sitting with the survivors and families in the first screening?

VIERCI: When I saw the film for the first time, it was with José Luis Inciarte, who is one of the survivors. Then he died a few months ago. J.A. came to Uruguay to show him the film, because he was sick. J.A. made the commitment to show the film to everybody.

DEADLINE: Obviously, José knew it was the end of his life, and it’s a very intense experience to be watching his story. What do you think he felt about the film?

BAYONA: It was very impressive to see how calm he was in front of death. He told us, “Don’t worry about me, I had a 50-year bonus, so I’m OK, and I’ve been there.” He had a near-death experience during the avalanche. He was not afraid of death at all, he was totally in contact with that idea, he was very present all the time, and actually what he was more scared of was not being able to watch the film. So, that’s why I jumped [on a plane] to Uruguay from Europe and showed him the film. He saw the film twice, also with the rest of the survivors, and he was even more happy about that, to have the chance to watch it with his friends from the mountain.

And what he was very impressed about in the film was the realism. He had the feeling that he was going back to the mountain, that he was again in the place, that he was going through the same, but he was happy to have something to show to [the families], and to make them understand what they went through. Also, I think it was important to show the people a different take — a take that doesn’t rely on easy ideas on heroism. There is no heroism in this story, it’s just the story of some miserable guys that crash in the Andes and have to eat the corpses of their friends. And suddenly, the incredible thing of crossing the Andes walking, and organizing a group that never left somebody behind, that was taking care of each other all the time, and did something extraordinary. It was ordinary people doing something extraordinary. They rejected this idea of heroism. All of them were happy to have a movie that was able to communicate that to the audience.

VIERCI: When we saw it with all the families, and the survivors, it was the most emotional moment in my life. José, the guy that died in July, he spoke a lot about Numa to J.A. and to me. He knew perfectly that Numa sacrificed himself — he says that word, ‘sacrificed’ — for the others. He was very happy that the voiceover was Numa’s.

When we showed the film to all the families, it was the value of confidence. Everybody, the survivors and the family of the deceased had confidence in J.A., in Belen and Sandra and Pablo. They’ve known me since we were children, most of them. But they didn’t know J.A., and Belén and Sandra. They had confidence because of one email that J.A. sent us. They met J.A. in 2016 and they were confident that J.A. was doing a journey with them, and with the deceased, with the 45 of that trip. They were confident because J.A. was going to do something authentic, the truth.

BAYONA: And also, Pablo, because one of the things that I like as a director is to provide the actor with the right atmosphere, to feed the actor with all the information, and then to provide the right atmosphere. This is why we shot in real locations. And in that sense, I really like to blend fiction with reality on set. To give you an example, Carlitos Páez, one of the survivors, is playing Carlos Páez, his father in the film.

The guy who reads the list, the real list on the radio, the moment that everybody remembers, when all of them, including Pablo, realized who was dead and who was alive, it was Cárlos Paez, a famous painter in Uruguay, who was reading that list. He has a very famous face, so I thought, who has that face? His son has his face. And suddenly we have Carlitos Páez, reading his own name [from the list of survivors] on screen. And on set, he was having a conversation with the real journalist that was with his father on the other side of the phone.

DEADLINE: So you not only have a survivor playing his own father in the moment he received the news of his survival, but on screen you have that survivor on the phone with the same journalist who broke the news to his father 51 years ago? That is just incredible.

BAYONA: The movie is full of details like that. Like when Numa gets back home at the very beginning of the film, and there’s somebody in the street, he says, “Goodnight.” That guy is the real nephew of the real Numa Turcatti. And we are shooting in the same house where Numa Turcatti lived.

DEADLINE: So, because you involved the families the whole time, it not only brought authenticity, but it made the survivors and the families feel included in telling the story.

BAYONA: I think you use the right word, to be included, because after so many years, and maybe the film they did before… I think I have the impression that was made too soon, so it was not possible to get to an agreement with the families of the deceased. But after 50 years, I think it was a good moment. And we did everything we could to make them feel comfortable, to trust us, even though they never read a single line of the script. They gave us everything, and of course we felt the responsibility of doing something that was at the level of what they were expecting.

VIERCI: Nando Parrado, one of the survivors said, “If you want to know what happened, you must see the Bayona film, Society of the Snow. This is the closest [version] of what happened, of that experience.

As Numa said, “Tell the story.” And then the story is in the audience, and the audience complete their story with his story, and it will never end. And this is the great thing of the film, that nothing is conclusive, you keep it in your mind and in your emotions. You go out of the cinema, or the TV set, and it’s your story. You are comparing your story with, what would I do in that situation? I think it’s a story that never ends. And the film is marvelous because it opens doors that are closed.

DEADLINE: How do you think making this film has affected you personally?

VIERCI: For me, I am older than J.A., really older. I have never grown up so quickly in the emotional sense, in the spiritual sense, [as] during this experience. This is something more than a film. Because I am so committed to what we did and what we see, I think that I’m a new person, a new guy, every time I see the film.

BAYONA: It was so interesting to have the chance of trying to decipher the mystery in Pablo Vierci’s book, what was left to tell. Because the survivors had the need to tell the story again, as much as I had it. So, it was a privilege to explore this story, and it was a beautiful treasure when we found out the heart of the film. That to me is the essence of understanding, that you and I are part of the same thing, we are the same. It’s such a relevant message nowadays, in a world that is constantly pitting us against each other, to understand that we are all part of the same thing, that we are the same. I consider myself very lucky to have found this story, and to have the privilege to tell it. It’s actually something that has been healing, not only for them, because it gave them the chance of giving voice to the other ones, the ones that gave them so much, but also to heal their families.

Best of Deadline

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Danielle Brooks To Receive Palm Springs Film Festival's Spotlight Award, Actress

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.