Palm Beach County's first Black doctor arrived in 1902 and had offices on Clematis Street

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

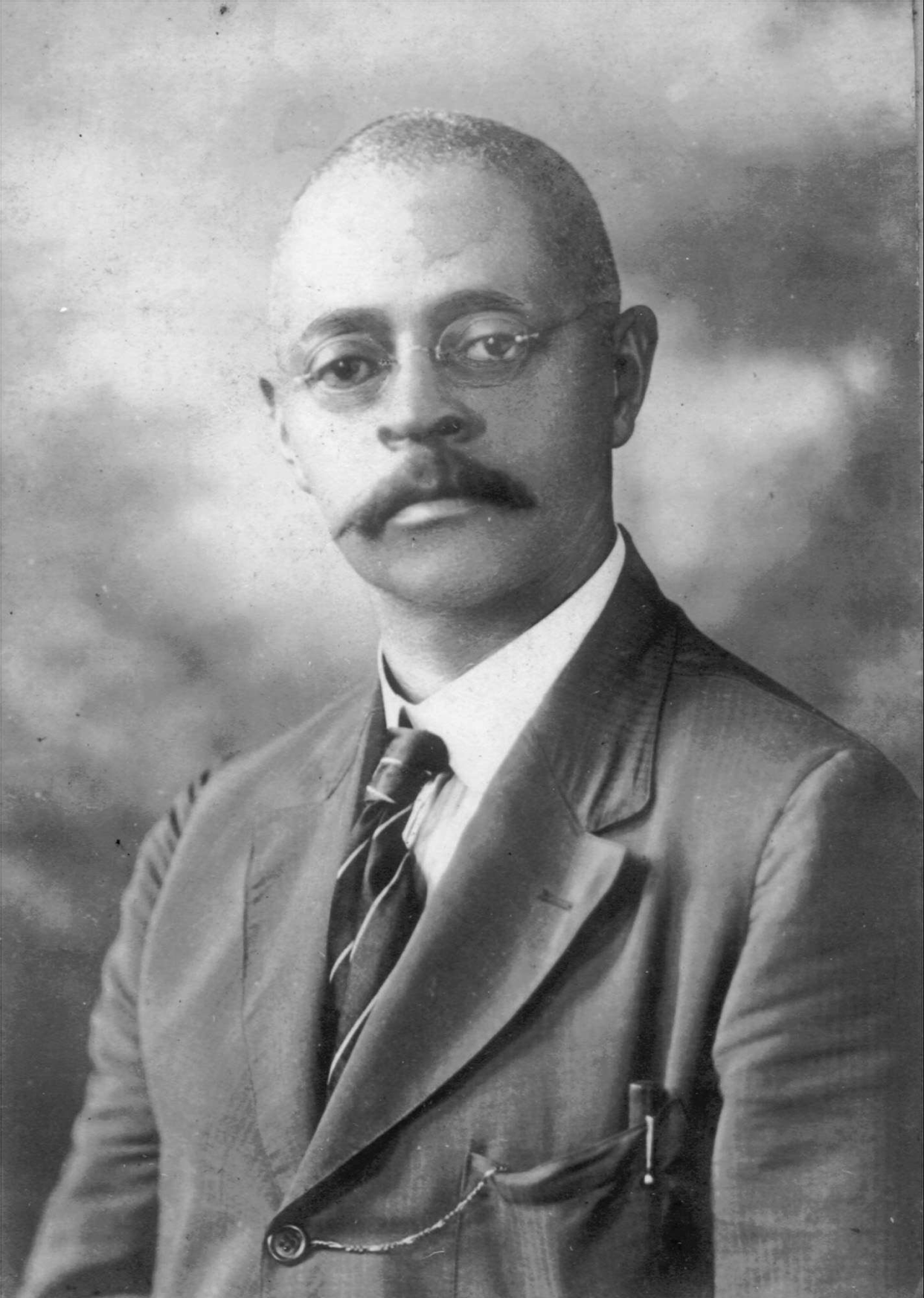

Thomas Leroy Jefferson toiled in Palm Beach County for more than three decades. As an Black man during Jim Crow, he worked mostly in obscurity. But the folks he healed knew him.

He was the doctor for the Styx, the pioneer Black settlement on Palm Beach island, and is believed to be West Palm Beach's first Black physician. He was on staff at the Pine Ridge hospital in the 1400 block of Division Avenue in West Palm Beach. At the time, Pine Ridge was the only hospital in five counties where Black people could go for help.

Folks around town called him "the bicycle doctor" because he would ride his bike to house calls. Today, Palm Beach County's historically Black medical society is named for him.

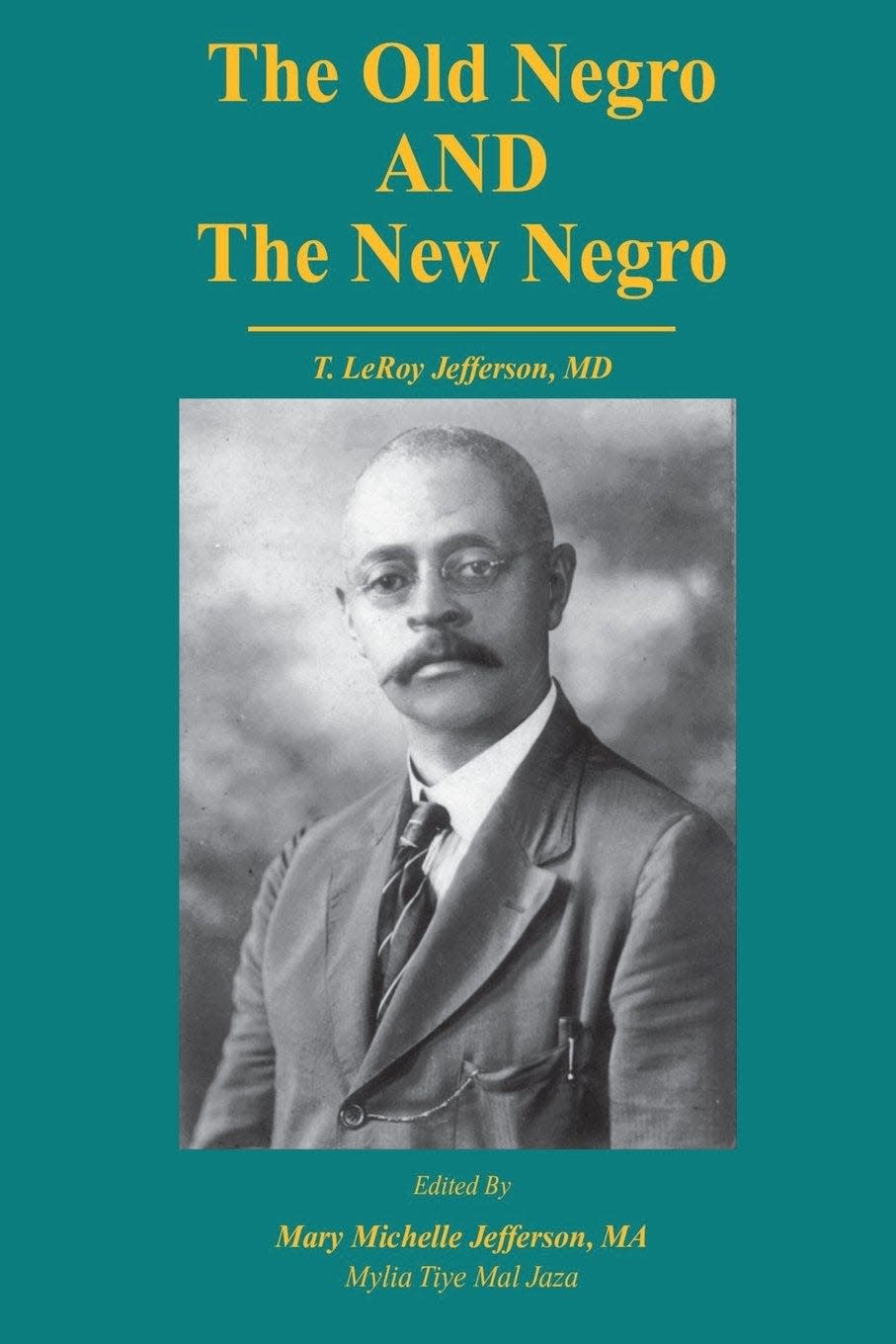

Late in life, Jefferson stepped away from medicine to write a treatise on the state of Black people in his era. The book was nearly lost to history, until two descendants intervened.

Jefferson was born in May 1867, just two years after the end of the Civil War, in southwest Mississippi.

Family legend once held that he was descended from the children of slave Sally Hemings and her owner, Founding Father and U.S. President Thomas Jefferson. But the family said it’s since learned the doctor was descended from a white slaveholder and Confederate combatant who married a Black woman — not a slave — and later changed his name from Thomas Meeks to Thomas Meeks Jefferson.

From schoolteacher to physician

Thomas Leroy Jefferson started his career as a schoolteacher in Cajun country, in New Iberia, Louisiana. He also ran a drugstore. He worked his way through school at a Black medical college in Nashville, Tennessee, graduating in 1892. He practiced in Orange, Texas, and in New Orleans, where his only child, Maude, was born in 1900.

As Jefferson began practicing his freshly acquired medical skills, other Black people were migrating to the wilds of what’s now the town of Palm Beach. They came to work on the great tourist hotels, and built a squatters’ village with discarded construction wood for themselves and called it The Styx.

Dr. Jefferson headed to South Florida in 1902 — relatives don’t know why, except perhaps just to be part of the gold rush. He became the doctor and pharmacist in the Styx. He also provided medical services to area Seminoles.

By 1911, Jefferson was on the mainland and had an office on North Olive Avenue in West Palm Beach. The 1916 directory listed him at 111-115 Rosemary Ave., at Clematis Street and across from what is now the city's police headquarters.

“The lean, tall, physician was a familiar sight in downtown,” longtime Palm Beach Post columnist Bill McGoun wrote in 1977, “pedaling his bicycle to work while puffing on one of his ever-present cigars, which he got from a cigar factory next to his office.”

Little written about his life, career

As with many Black people of his time, Jefferson didn’t make the newspaper too often. A legal announcement shows he sold a piece of property in 1904 to Mary Hone, whose husband Richard was the victim two years earlier of one of the fledgling town’s most sensational murders. In 1904, the Miami News’ “Colored Column” mentioned that Jefferson had gotten into the poultry business. Other News columns mentioned visits to Miami.

In April 1915, Jefferson was one of three Black men arrested in West Palm Beach on charges they wore Elks badges at a time when the organization banned Black lodges. Charges were dropped a year later.

Jefferson was 60 when he retired in 1927. Two years later, the stock market crash wiped him out, and he went back to work. Pointing at his medical bag, he’d say, “I can always make a living at this.”

“If he bought an automobile, he paid for cash for it,” son-in-law Carl Robinson told McGoun in 1977. “He would put so much in savings every night for a vacation the next year. When he died, he owed 35 cents, and that was for a week’s laundry.”

Resurrecting the doctor's book

In 2006, two descendants re-issued "The Old Negro and the New Negro," a book Jefferson had published in 1937, just before his death. Mary Jefferson, whose grandfather was Jefferson’s nephew, and Ollie Jefferson, the doctor’s grandniece, had tracked down two copies at a college and retyped the manuscript.

A December 1937 Palm Beach Post story said Jefferson’s book was “designed to instruct his own race and enlighten his white readers.”

Jefferson said in the book that he wrote it “to point out to my people some of the errors they (Black people) are making that are holding the Negroes back as a race.”

“Truth always hits people like a freight train,” Mary Jefferson said Jan. 18 from Chicago. “There still are some people who don’t care of themselves and don’t hold their own accountable for wrongdoing.”

Jefferson wrote that the key to the “new negro” was, not surprisingly, health care. Reduced infant mortality, healthy births, prenatal care, proper nutrition, regular child checkups, vaccines, and acts as simple as proper bathing.

The doctor “did not talk much outside of the examination room, but inside he took a long time just talking to his patients. He believed in patient education,” daughter Maude Katherine Jefferson — who died in 1999 — told author Leon Fooksman for the book "A Tradition of Caring, A History of Medicine in Palm Beach County," published in 2013.

Jefferson wrote that “...if the Negro race of America is ever to take its rightful place in the civil, political, industrial, intellectual and financial affairs of America we must raise up and educate men — men of ability, men who will with their tireless energy, their indomitable courage, their forceful eloquence and their logical diplomacy, go into the halls of Congress, into the state legislatures, before the courts of the land and out into the world at large and plead the cause of the Negro people.”

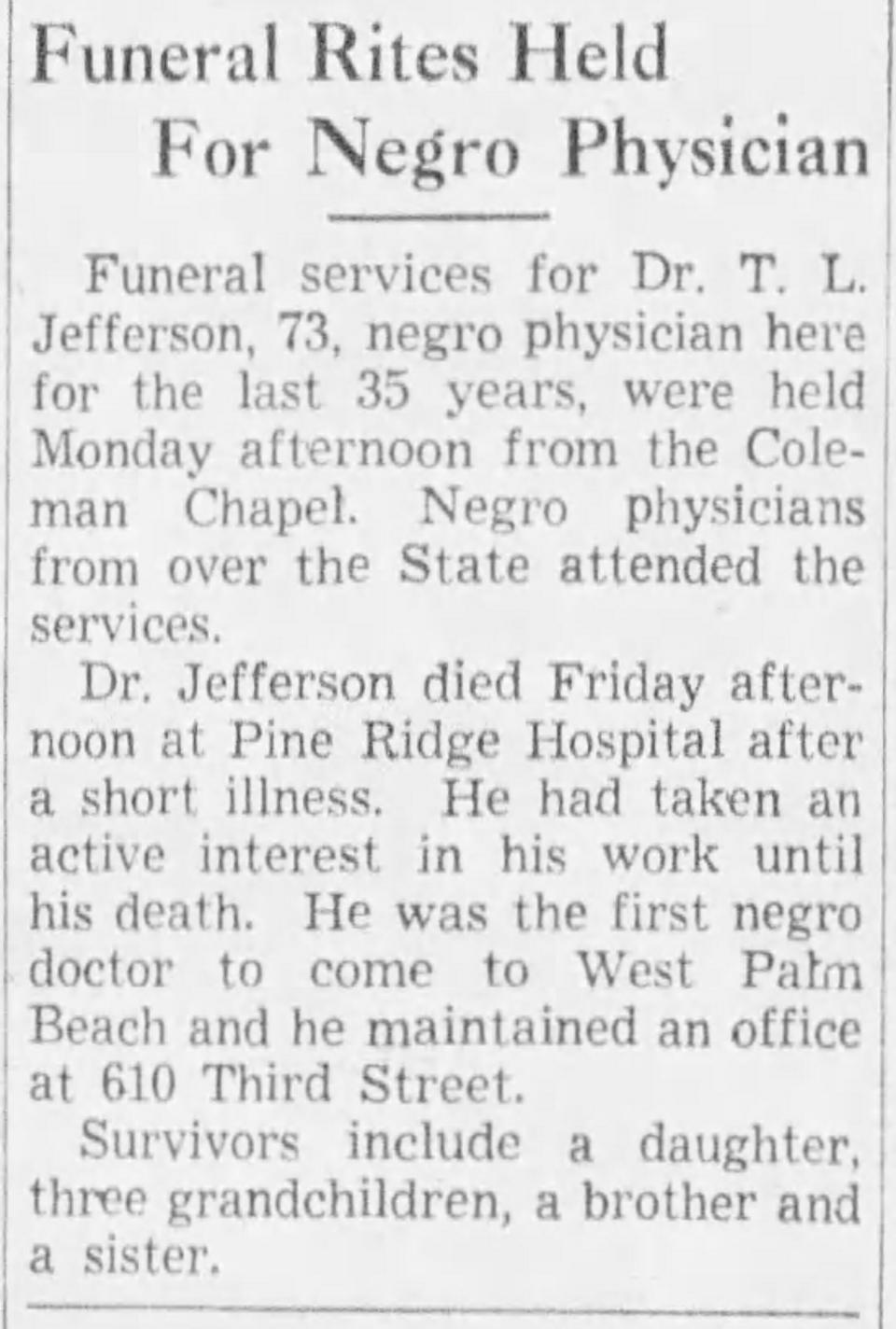

Becoming a patient himself

In September 1939, Jefferson, then running an office at 610 Third Street, went into his old hospital, Pine Ridge, to have an appendix removed. Relatives don’t say what might have gone wrong, except to cite the limits of medicine in the 1930s, especially among Black people. But Jefferson died days later, on Sept. 29, at age 72. He was survived by his daughter and three grandchildren.

In 1947, eight years after Jefferson’s death, the T. Leroy Jefferson Medical Society would be founded. The Black-based medical group later disbanded, but it reformed in 1991 and again in 2001. It has about 250 members.

Thomas Leroy Jefferson was buried in West Palm Beach’s segregated Evergreen Cemetery. A brief story in the Post about his funeral read, “Negro physicians from over the state attended.”

“To the Black community,” Ollie Jefferson said in January, “he would not have been invisible, but vital.”

Sources: Palm Beach Post, Historical Society of Palm Beach County, T. Leroy Jefferson Medical Society, and "A Tradition of Caring, A History of Medicine in Palm Beach County," by Leon Fooksman (2013).

Eliot Kleinberg retired in December 2020 after 33-1/2 years as a staff writer at the Palm Beach Post. He authored the longtime history columns Post Time and Florida Time.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Thomas Leroy Jefferson was Palm Beach County's first Black doctor