Over the edge: The incredible life and mysterious death of Peter Ivers

Late on a Saturday afternoon, it is clear the gentrification that has reshaped so much of Los Angeles’ downtown over the past decade has yet to fully flower on this particular stretch of 3rd Street. A few blocks away, you’ll find the chic literary emporium the Last Bookstore and crowds heading toward the culinary delights of Grand Central Market. But here, the stores are selling wholesale cigarettes and smoking “apparatuses” — while the few pedestrians must walk around a homeless man sleeping by the entrance of an urgent-care clinic. Even so, the neighborhood is much improved from its condition in the 1970s and ’80s, according to retired Los Angeles Police Department detective Cliff Shepard.

“That was my patrol area when I was working the foot beat [in the mid-’70s],” says Shepard. “[It was] terrible.” On March 3, 1983, Shepard was on his daily commute when the report of a homicide in the area caught his attention. “I heard on the news that somebody involved in Hollywood who had been living in the area had been murdered in his apartment,” he says. “The thought to me was ‘If somebody from Hollywood is living in Skid Row, he’s nuts.’”

The victim was a boyish-faced 36-year-old singer, songwriter, harmonica player, and TV host named Peter Ivers. A neighbor in an adjoining loft discovered Ivers’ body in the musician’s sixth-floor dwelling on the afternoon of March 3. His head had been bludgeoned. An autopsy revealed he died from massive fractures of the skull with brain injury.

The day after Ivers’ body was found, the police stated there were no suspects in the case. No one was ever arrested for Ivers’ murder, and his death remains a mystery. There are numerous theories about what might have occurred in that loft, although almost four decades later, the number of people considering the matter, or who remember Ivers at all, is small. Even the dramatic manner of his passing has not cemented Ivers’ place in history. Given the lack of commercial success he had during his lifetime, that isn’t a huge shock — though it is a shame, at least according to his friend Van Dyke Parks, the legendary songwriter and Beach Boys lyricist. “He did not get his just deserts,” Parks says. “That should not make me angry. But it sure does make me sad.”

Perhaps it is fitting that Ivers’ name does not register to most in the mainstream, given how he enjoyed working and living on the fringes — introducing bands such as the Dead Kennedys and Fear on TV while spouting off head-scratching manifesto rhetoric like “Why glow in the dark when you can dance on Superman’s grave?” “He was in a kind of world of his own,” says Ivers’ friend David Lynch. But without Ivers, diverse aspects of pop culture — from Lynch’s full-length directorial debut, Eraserhead, to the punk scene to even MTV — might have wound up as different entities. He was the most adventurous and fearless of artists, and while the details of his death remain mysterious, those qualities may have in some way led to his early passing. Or, as Lucy Fisher, his longtime girlfriend and now Hollywood producer puts it, “Peter liked the edge.”

For Ivers, sometimes “the edge” meant moving into a dangerous neighborhood, and sometimes it meant getting booed mercilessly by a crowd while opening for one of the biggest bands in the world. That’s what happened to the singer in the late summer of 1976 when he supported Fleetwood Mac at Los Angeles’ Universal Amphitheatre. “Oh God, the night from hell,” says Fisher with a shudder. Fisher’s recollection of that evening is that Ivers came out in a diaper and was then heckled. “The audience was not prepared for him,” she says. “They just wanted Fleetwood Mac, and they really did not understand any of the conceptual-art stuff he was doing.” While the Fleetwood Mac show was something of a professional nadir for Ivers, it was not out of character. “Peter was an inveterate iconoclast,” says Parks. “His general demeanor was antiauthoritarian.”

Ivers grew up just outside of Boston in Brookline, Mass., and was encouraged in his artistic pursuits by his mother, Merle. He later attended Harvard, immersing himself in a theater scene whose members included Stockard Channing, John Lithgow, and Tommy Lee Jones. In his second year at college, Ivers took up the harmonica, a choice that hinted at his individualist streak. “One of the things that made him so singular was the harmonica,” says Parks. “The herd was stampeding to either guitars or the piano. The harmonica put him in a singular place.”

That place led to a record deal with Epic, but Ivers’ debut album, 1969’s Knight of the Blue Communion, was a commercial failure and he was soon dropped by the label. A move to California with Fisher — who began dating the musician while in college — led to work scoring films for young directors like former college classmate Tim Hunter (who would later direct 1987’s River’s Edge), and Ivers nabbed another record deal, this time with Warner Bros. However, his two Warner albums (1974’s Terminal Love and 1976’s Peter Ivers) underperformed, the idiosyncratic tunes having more in common with the new-wave sound of the late ’70s than anything popular at the time. “He was an intellectual pop artist,” says Lynch. “You could say he was ahead of his time.”

With Ivers’ antics opening for Fleetwood Mac failing to galvanize sales, the singer-songwriter once again found himself without a label, so he moved back into soundtrack work, overseeing the music for Ron Howard’s 1977 directorial debut, Grand Theft Auto. “[Film] executives liked him,” says drummer Russell Buddy Helm. “He could talk the talk. He contacted me for Ron Howard’s thing, and Peter recorded some of his own songs on Ron’s money — which was really his alternative motive. [Laughs] Ron was cool. He came in, he didn’t mind.”

Lynch was feeling fraught when he first approached Ivers about writing the music for a song to appear in his 1977 debut feature, Eraserhead. “I was really embarrassed about my lyrics because they’re so simple,” says Lynch. “Pete said, ‘No, I love them.’ I came back to Pete’s house two weeks later. He laid down on his bed, propped himself up on pillows, took a microphone, and sang right in front of me what is in the film.” The haunting “In Heaven” (performed by the voluminously cheeked “Lady in the Radiator”) stands as Ivers’ most notable contribution to both music and film, and has been covered by acts such as the Pixies, Bauhaus, and Devo.

“It’s almost childish, the song,” says Devo bassist Jerry Casale. “But it was dark and foreboding at the same time. It was like a nursery rhyme turned on its head.” Casale met Ivers when the band visited Los Angeles. “He knew everybody,” says Casale. “He was everywhere on any given night. He was quite a larger-than-life character.” Ivers had a wide and diverse circle of friends, from musicians to video artists to Hollywood notables and up-and-comers like Lynch, Animal House co-writer Doug Kenney, John Belushi, and actor-director Harold Ramis, who would help produce Ivers’ early-’80s stage project Vitamin Pink Fantasy Revue. “He was such a touchstone for so many people in so many different walks of life,” says Fisher. “That was one of his other major gifts.” If only the artist could find the perfect outlet for his equally irreverent personality and music.

Ivers’ exhibitionist side would be given free rein in the early ’80s when he started to host the L.A. cable access show New Wave Theater. The program was conceived by producer David Jove (born David Sniderman), an enigmatic figure who, while calling himself Acid King, had reportedly supplied the drugs for which Rolling Stones members Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were infamously arrested in 1967 at Richards’ country home, Redlands. (Both were acquitted.) “David Jove was a fledgling artist, director, gang leader of the freaks and misfits that made up his own cast of really odd people,” says another Ivers friend, musician Peter Rafelson. “They would come and hang out in a small retail shop that he had converted into a cave without light covered in trinkets, knickknacks, pictures.”

Jove conceived New Wave Theater as a showcase both for performances by bands from the flourishing punk scene and for his self-penned antiestablishment screeds, which Ivers recited on air while dressed in outlandish garb. The show also found Ivers interacting with guest cohosts — including both Kenney and Lynch — and asking members of the bands to explain the meaning of life. Over time a host of punk acts, including Bad Religion, Circle Jerks, and Black Flag, appeared on New Wave Theater. “It was a madhouse,” says Lynch.

The series went national when USA network picked up New Wave Theater and broadcast it as part of its Night Flight programming block, turning Ivers into a cult figure. While the program may have been considered “edgy” at the time, much of its format and personality would soon become familiar thanks to a new cable network. “Again, Peter Ivers was ahead of his time,” says Josh Frank, author of the Ivers biography In Heaven Everything Is Fine. “MTV came around, and music television, punk rock, all of that became [mainstream] entertainment. New Wave Theater was way more important than it has ever gotten credit for.” And that extends to its host — described by one Night Flight producer as a “new-wave Dick Clark” — who never achieved the recognition of the TV VJs who followed.

By the early ’80s, Ivers and Fisher’s relationship was breaking down, and the musician decided to relocate downtown. Saying he wanted to “get into the art community,” Ivers asked Helm to help him find somewhere to live. The space the drummer found for him was large but basic. “It was not an apartment,” says Helm. “These were very crude, large loft spaces previously used for industrial businesses.” Fisher recalls being alarmed at her ex’s new neighborhood. “Yeah, I was concerned,” she says. “He wanted a bigger space where he could rehearse. But it was a scary place.”

That concern would prove horribly justified. Around 2:30 p.m. on March 3, 1983, Ivers’ friend Anne Ramis (Harold’s then-wife) became worried that Ivers had not returned her calls and asked his neighbor to check on him. It was the neighbor who found Ivers’ body: fully clothed, on bloodstained sheets. Nearby was a massive wooden hammer that one of the building’s other residents had left in a communal kitchen for their protection. “He’s lying in bed, and there was one of those circus hammers, and there was blood on it,” says Hank Petroski, one of two detectives on the case. “His head was smashed in.” It would later be reported that the lock to the front door of the loft had been jimmied open, but Fisher recalls that “the door wasn’t locked, which was really stupid.” Either way, it wouldn’t have been hard for an intruder to gain entry. “It was so easy, it was very unsecure,” says the now-retired Petroski. “One of those locks, you just rattle it a few times and the door opens.”

Fisher was unhappy with the police investigation from the beginning. “By the time I got [to the loft], people were already milling around,” she says. “They hadn’t cordoned it off, which was basically 101 of what you do at a murder scene.” Petroski admits that the situation was not ideal. “Oh no, it was crummy,” he says. “I would have been so pissed at the patrolman, because their job is to secure [the scene].”

Petroski recalls the hammer bore no fingerprints. But the crime scene did yield one clue — missing stereo equipment. “You could see where the stereo equipment would have been,” says Petroski. “There were some wires still there. So it was obvious that something was missing from the shelf. Now, that could have been a thing to fake us out — ‘I’ve already killed him for this, but now I’m going to steal his stereo equipment and then they’ll think it’s some burglar.’ ”

In the weeks that followed, Petroski questioned Ivers’ friends but was unable to come up with a credible suspect. Then he learned that a burglar had fallen to his death in the area. Given the stolen stereo, Petroski theorized that the same thief might have been responsible for the killing. “But we couldn’t prove it,” says Petroski, “and the case eventually kind of died.” Fisher, meanwhile, hired a private detective to look into the murder. “I did continue on for close to a year,” she says. “After a year, I decided I wasn’t going to open that door anymore, the door to that room, because the room was a bad room.”

Some friends believe another figure may have played a part in Ivers’ death: Jove, his New Wave Theater boss. While Ivers had a reputation of being merely offbeat, Jove was, to many, downright dangerous. Devo members found the producer so unnerving when they met him that the band never appeared on the show. “We were afraid of him,” says Casale. “He was a scary kind of loose cannon.” According to Helm, Jove — who died in 2004 — was angry at the possibility of Ivers leaving the show. “Peter was having difficulties with David Jove and New Wave Theater,” says the drummer. “David Jove was obsessive and quite the cocaine abuser. Peter was really kind of sick of doing David’s scene. David [was] connected with some serious punkers, and some of them were violent, and David himself could be violent.”

But law enforcement never seemed sold on any connection to Ivers’ death. In 2006, the case was reexamined at the instigation of writer Frank, who was in the early stages of writing his Ivers biography and had contacted Cliff Shepard, the onetime downtown beat cop who was then working for the LAPD’s homicide cold-case unit. “I looked at the work that had been done by the detectives at the time,” says Shepard. “They came up with a suspect, who was a rooftop burglar who fell off a roof, as being the most likely suspect. I know there are a lot of people that think there’s other people involved, but it doesn’t appear that way. You would like to have better answers, but I don’t think there ever will be. I think this is it.”

Perhaps the saddest twist in the story of Peter Ivers’ death is that the widespread success that had always eluded the artist was closer than ever at the time he was killed. Not only was Ivers hosting a nationally broadcast TV show, but he also had recently teamed with another songwriter, Franne Golde. Their composition “Little Boy Sweet” was recorded by June Pointer (of the Pointer Sisters) and appeared a few months after Ivers’ death on the soundtrack for the Ramis-directed National Lampoon’s Vacation. And the weekend before Ivers’ killing, Diana Ross recorded their song “Let’s Go Up,” which was released as a single later that year. “I honestly think the sky’s the limit,” says Fisher about what Ivers might have accomplished. “He was very entrepreneurial, and he had his finger on the pulse.”

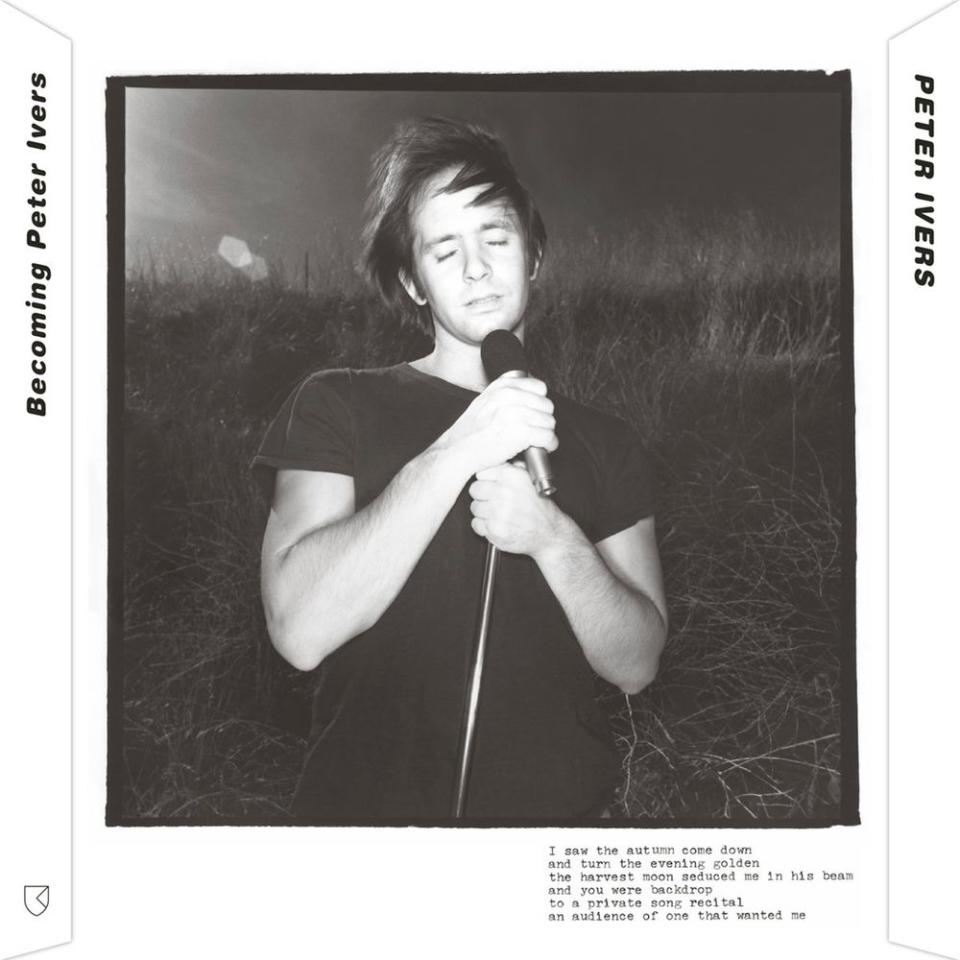

As a former vice chairman of the Columbia TriStar Motion Picture Group at Sony and current co-president of Red Wagon Entertainment, Fisher herself is now a major Hollywood player. She has also done her best to keep Ivers’ name alive. Shortly after his murder, she founded the Peter Ivers Visiting Artist Program at Harvard. More recently, Fisher gave her blessing to a recently-released collection of previously unheard demos and other tracks, Becoming Peter Ivers. “Whenever I hear people responding to his music, it makes me happy, because it would have made him so happy,” she says. “He could win over fans one at time. He just didn’t have enough time.”

Related content:

—Why David Lynch’s Eraserhead is the perfect Halloween movie

—The tragic, unsolved murder of Hogan’s Heroes star Bob Crane

— ‘Hollywood Ripper’ who killed Ashton Kutcher’s friend and another woman has been convicted