Oscars Flashback: The tragic life and death of former Disney star Bobby Driscoll

Paperback mysteries usually end this way, not Disney fairy tales. In March of 1968, a pair of children playing in an abandoned, Greenwich Village tenement in New York City discovered a young man dead on a cot, surrounded by beer bottles and religious handouts. There were no obvious signs of foul play. He had no identification. The body was unknown and went unclaimed.

After failing to locate his next of kin, authorities declared the man dead from hardening of the arteries — a common side effect of longtime heroin abuse — and buried him in a mass, unmarked paupers’ grave on the Bronx’s Hart Island alongside other unidentified bodies and indigent souls who had fallen on hard times. And somewhere — although nobody is sure exactly where — on that island that once housed a woman’s psychiatric asylum, a men’s prison, and patients quarantined during an outbreak of yellow fever in the 1870s, is the final resting place of Peter Pan.

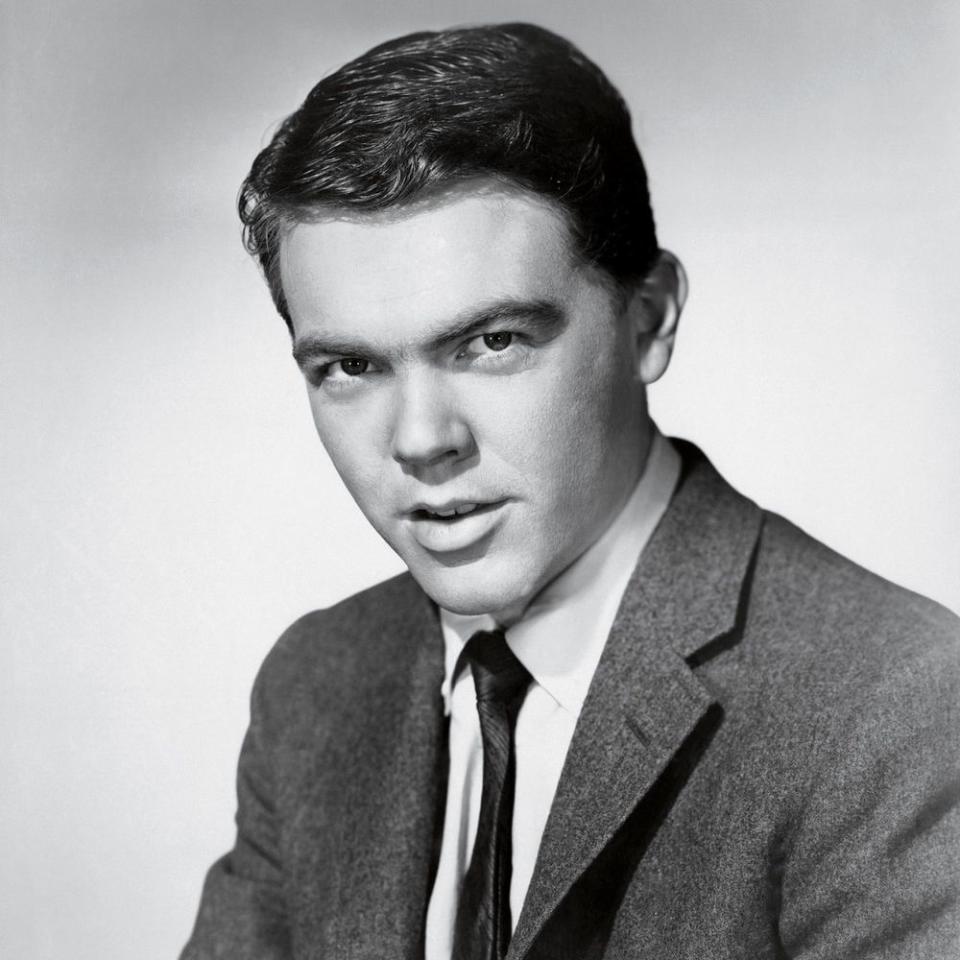

It’s also the final resting place of Bobby Driscoll, who became a household name at the age of 9 with a starring role in Disney’s controversial Song of the South. He won an Oscar at 12, and then, at 16, went on to voice the title role in Disney’s classic animated film about a boy who never wants to grow up. In this case, that boy’s twisted road to manhood ultimately detoured into (and out of) jail, through multiple marriages (and divorces) to the same woman, and finally winding through Andy Warhol’s Factory to a tragic end.

So how to explain a former child star who worked alongside Tinseltown greats like Charles Boyer, Alan Ladd, Roy Rogers, and Joan Fontaine falling so far from a life of klieg lights and Academy awards to become just another indigent in an unmarked grave on Hart Island, where his body remains today? Fifty years after his death, it’s a question that continues to trouble some of his oldest friends.

“He didn’t really recover from being abandoned by Hollywood,” reflects actor Billy Gray, who played Bud Anderson on the classic sitcom Father Knows Best and later befriended Driscoll. “It hit him hard. He was a heroin addict. It was tragic and there wasn’t much you could do about it. He was strong, he had a good intellect and he should have known better. But that was a choice he made, and you couldn’t talk him out of it.”

It all started with a haircut.

The only son of an insulation salesman and former schoolteacher, Driscoll was discovered at the age of 5 while getting a trim. “A barber in Pasadena told me I should be in the movies, so one Sunday he invited us out to his home and his son was there,” recalled Driscoll during a 1946 radio interview. “We found out his son was in the movies, and his son got me an appointment with his agent. His agent took me out to a part.”

It was only a bit role opposite Margaret O’Brien in the 1943 film Lost Angel, but it led to a succession of movies that capitalized on Driscoll’s pert nose and freckled face. Driscoll made nine films in a three-year span before his breakout role as Johnny, a 7-year-old boy who visits his grandfather’s plantation in Song of the South.

Though the live-action/animated musical (which featured the Oscar-winning “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah”) would ultimately represent an embarrassing chapter in Disney’s storied history because of its offensive stereotypes and candy-coated depiction of slavery, it marked the start of a successful relationship between the studio and Driscoll, who became the first male actor to ever secure a Disney contract. “What Disney saw in Driscoll was the perfect, wholesome, all-American kid who dreams of being with pirates and all that,” explains Hollywood biographer Marc Eliot, author of Walt Disney: Hollywood’s Dark Prince. “Bobby was Disney’s live-action Mickey Mouse.”

The budding star made four movies for Disney, including Treasure Island, Peter Pan, and So Dear to My Heart — which, together with his role in The Window for RKO Pictures, earned Driscoll the Juvenile Academy Award in 1950. He also made friends with castmates along the way. “He was very lovely,” adds Kathryn Beaumont, 82, who starred opposite Driscoll as the voice of Wendy in Peter Pan. “He went to his own public school when he was not working. He had normal experiences with his peer group — just as I did.”

By the time Driscoll voiced Peter Pan at 16, however, he no longer had the impish face that kept him gainfully employed as a youth. He was just another teen boy with a bad case of acne. In today’s world, it’s a familiar and predictable narrative — a star who began his or her career on the Disney lot grows up and out of the squeaky-clean confines of the studio. But contemporary actors like Miley Cyrus and Selena Gomez willingly left the Mouse House; Driscoll didn’t have a choice when the studio unexpectedly dropped its golden child in 1953.

“When Howard Hughes bought RKO, he, in effect, became the owner of the Disney studio,” explains Eliot. “He controlled the money and he hated Bobby Driscoll. He hated Hollywood kids. He thought they were precocious, weren’t real, and were incredibly annoying. He didn’t want Bobby Driscoll to be with Disney anymore.”

The split was devastating. “The way I understand it, it was a rather rude dismissal,” says Gray. “I heard that he was informed that he was no longer under contract through them by driving up to the entrance and being refused entrance into the studio. That was his notification that he was no longer needed there.”

Trying to forge a new path, Driscoll left his parents’ home at 16 and made trips to New York City to study acting. He reportedly enrolled in UCLA and Stanford but ended up dropping out of both because he couldn’t find his way. “I wish I could say that my childhood was a happy one, but I wouldn’t be honest,” he said in a 1961 magazine article titled “The Nightmare Life of an Ex-Child Star.” “I was lonely most of the time. A child actor’s childhood is not a normal one. People continually saying ‘What a cute little boy!’ creates innate conceit. But the adulation is only one part of it.… Other kids prove themselves once, but I had to prove myself twice with everyone.”

Though his big-screen career fizzled, Driscoll found fairly steady work in TV shows like Dragnet and Rawhide and attempted to settle into a life of domesticity with Marilyn Jean Rush, a 19-year-old he met in Manhattan Beach. After eloping to Mexico five months after they met, the young couple had one son and two daughters before splitting for good three years, two marriages, and two divorces later. “I became a beatnik and a bum,” Driscoll said in the 1961 magazine article. “I had no residence. My clothes were at my parents’ [house] but I didn’t live anywhere. My personality had suffered during my marriage and I was trying to recoup it.”

While hanging out on Los Angeles beaches, Driscoll befriended a group of young Hollywood turks like Gray, Robert Blake (Baretta), Dean Stockwell (Quantum Leap), and Russ Tamblyn (West Side Story). “We used to play pool together,” remembers Tamblyn of their days living and carousing in Pacific Palisades. Driscoll also engaged in a more dangerous form of recreation — heroin. “It wasn’t a secret,” says Gray. “He liked heroin. That’s just the way it was.” r

Driscoll then started to spend time in Topanga Canyon with Beat Generation artist/photographer Wallace Berman and began dabbling in verse. He even created collages and small works of art. “We loved him dearly,” remembers Berman’s wife Shirley, now 83. (Wallace Berman died in 1976). But trouble was never far away. Driscoll was arrested multiple times for drug possession, assault, burglary, and check kiting before he was finally committed for drug rehabilitation to Chino Men’s Prison in 1961. “I had everything,” he said in an interview after his sentence. “Was earning $50,000 a year…working steadily with good parts. Then I started putting all my spare time in my arm. I’m not really sure why I started using narcotics. I was 17 when I first experimented with the stuff. In no time at all, I was using whatever was available…mostly heroin, because I had the money to pay for it.”

Prison sentences were the kiss of death for Hollywood actors in those days, so after briefly working as a carpenter, Driscoll left his young children behind and moved to New York City in 1965, where he forged an unlikely relationship with, of all people, Andy Warhol.

“Bobby was a curiosity. He wasn’t really part of the crowd,” says Eliot, who remembers seeing Driscoll in the ‘60s in a Greenwich Village club. “Warhol was so perverse, that he loved having Bobby Driscoll as part of his scene. That was Warhol’s perversity in full play — you know, dissipated Hollywood.”

No one seems to know how the then 31-year-old Driscoll spent his final days in New York City and why he ended up in an abandoned apartment where those kids found his body. Unlike the celebrity missteps that are chronicled hourly on news sites and social media today, Driscoll’s demise happened in complete and total silence.

Driscoll’s mother, Isabelle — who had not heard from her son in years — found out about Bobby’s death nearly a year and a half later after placing advertisements about his disappearance in New York newspapers. It would take even longer for word to reach the public at large, as news of the Disney star’s passing only surfaced four years after the fact, during the rerelease of Song of the South in 1972.

Eliot has a far more sobering rationale. “Obviously he was sick and an addict and broke. Nobody came to his rescue. That’s the real story of Hollywood. It’s a very sad story, but, you know, take a look at A Star Is Born. It’s the exact same story.”

It’s the first Sunday after Thanksgiving and a family is busy setting up chairs on the 1500 block of Vine Street in Hollywood. In less than two hours, the annual Hollywood Christmas Parade will travel down the street, so the family positions itself right in front of Bobby Driscoll’s Hollywood Walk of Fame star. No one takes notice beneath their feet, though a little girl pops a bubble that a street vendor just blew her way right on top of the star.

Does anyone here even know the name at the center of those five points? “He sounds like a baseball player to me,” offers a patrolling police officer with a shrug. If it weren’t for the fact that the Walk of Fame isn’t known for honoring athletic achievement, it would be a good enough guess. Driscoll’s name has long faded from mainstream recognition, but there have been attempts to keep his memory alive in the decades since his death.

A New Jersey woman who prefers to remain anonymous quietly maintains a website devoted to Driscoll’s life and career. Russ Tamblyn flirted with the idea of doing a movie about his old pal before deciding he’ll devote a chapter or two to Driscoll in his upcoming autobiography. “I thought it would be incredible,” says Tamblyn, who is believed to have some of Driscoll’s creations from his bohemian days. “I did study him for a long time. I talked to a priest at the prison that he was in, and I got Bobby’s prison records.”

For his part, Allender just wants to see Driscoll remembered for his achievements, not his shortcomings. “What’s the point of poking at it?” he says of Driscoll’s drug use. “People make mistakes. Some people can’t get out of it. I’m just saying, respect him.”

That’s what a New York City charity is trying to do for Driscoll and all the other people who were buried and forgotten on Hart Island. In 2011, the Hart Island Project was created to make it easier for people to find out whose remains ended up on the one-mile stretch of land. “Bobby is probably the most famous person buried there, along with novelist Dawn Powell,” says president Melinda Hunt. “There are a number of interesting characters from New York City — the cool people.”

Regrettably, Driscoll’s children will never see the exact spot where their father was laid to rest: Burial records from 1961 through July 1977 that had been kept in the old hospital were destroyed by a fire. “He’s somewhere on the northern part of the island,” says Hunt. “We just don’t know where.” But that hasn’t stopped her from encouraging Driscoll’s children to visit the island, which for now is open only to next of kin. “My feeling is that it’s not a shameful place to be buried,” says Hunt, who hopes to someday see the cemetery accessible to the public. “It’s a really, really beautiful location. There are herds of deer, these red raccoons, and a whole bird sanctuary. So for Bobby Driscoll, it’s the perfect place to be buried. It’s just like Never Never Land.”

Read more from EW’s Pop Culture True Crimes Series:

Adam Jasinski: Confessions of a reality TV felon

Hollywood’s original gone girl

Wrong turn: Amy Locane’s sad journey from movies and TV to prison