In Oscar Music Race, Familiar and Fresh Faces Seek Score Nominations

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This year’s Oscar-worthy music is the most interesting mix in years. Veterans continue to supply well-crafted, traditional orchestral scores while new voices are contributing surprising sounds for daring filmmakers seeking something fresh.

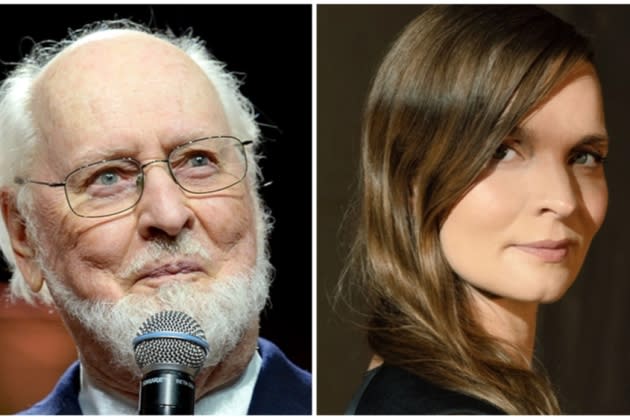

Let’s start with the most familiar duo: John Williams and Steven Spielberg. Seventeen of their 29 films together have been nominated for Oscars, and three have won (“Jaws,” “E.T.” and “Schindler’s List”). Their newest film, “The Fabelmans,” is already a critical favorite and seems poised to become the 90-year-old composer’s 53rd Oscar nomination.

More from Variety

Oscar Predictions: Best Supporting Actress - What Do We Make of Keke Palmer's NYFCC Win for 'Nope?'

Oscar Predictions: Best Supporting Actor - Ke Huy Quan Is a Story Worth Honoring This Season

Williams knew Spielberg’s parents, who figure prominently in this autobiographical film. His warm, nostalgic and sometimes melancholy score reflects the ups and downs of their marriage. He recruited Los Angeles Philharmonic pianist Joanne Pearce Martin for the several classical pieces and the piano solos of the dramatic score – which, Williams hints, may be his last for his longtime collaborator.

Another past Oscar winner, Icelandic composer Hildur Guðnadóttir (“Joker”) is a leading contender for two scores: Todd Field’s “Tár” and Sarah Polley’s “Women Talking.” She wrote music for “Tár” that was played for the actors (notably Cate Blanchett as a world-class symphony conductor) but not heard in the final film; much of her dramatic score is barely audible, designed to be felt more than heard.

Her music for “Women Talking” is among her most accessible, written primarily for acoustic guitars to reflect the rural American setting. She struggled with the subject matter – sexual assaults on women in a religious community – but ultimately agreed with Polley that the music needed to be “a vehicle of hope and forward movement.”

The #MeToo movement also figures strongly in Nicholas Britell’s score for “She Said,” which chronicles the determination of two New York Times reporters to pull back the curtain on Harvey Weinstein and his alleged assaults on multiple women.

Britell (a three-time Oscar nominee and Emmy winner for “Succession”) enlisted his cellist wife Caitlin Sullivan to assist him in creating a string-based score that would complement Maria Schrader’s film. Sometimes emotional, sometimes edgy, the score for Sullivan’s cello, Britell’s piano and a 15-piece New York City string ensemble carefully charts this sensitive and difficult road.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, who already have two Oscars apiece (for “The Social Network” and the animated “Soul’) are also in contention for two films: Sam Mendes’ “Empire of Light” and Luca Guadagnino’s “Bones and All.”

Their score for Mendes’ touching film about a troubled woman who works at a movie theater on the southern coast of England in the early 1980s is unexpectedly piano-based, the result of months of experiments and consultation with the director. Among the Nine Inch Nails duo’s most evocative scores to date, coupled with Mendes’ “magic of cinema” theme, “Empire” seems more likely to attract Academy voters’ attention than the darker, more violent “Bones and All.”

Piano is also prominently featured in Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch’s score for “Living,” with Bill Nighy as a 1950s London bureaucrat nearing the end of his life. The inevitable sadness is balanced with a sense of hope in her score.

Few composers are better at evoking the sounds of a specific region than Canadian-born Mychael Danna, whose ethereal vocals and mystical sounds for “Where the Crawdads Sing” could bring him awards attention. Danna won the Oscar for his elaborate, world-music infused tapestry for “Life of Pi” nine years ago.

For “Crawdads,” Danna added the Southern flavors of banjo, fiddle and autoharp but also finds unique colors in the sounds of sea shells and conch shells.

Curiously, regional colors don’t figure in Carter Burwell’s score for “The Banshees of Inisherin.” letting the small-town Irish setting and characters speak for themselves rather than emphasize the locale with music. Instead, the two-time Oscar nominee (“Carol,” “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri”) chose the fairy-tale sounds of celeste, harp and flute for the apparent innocence of Colin Farrell’s character.

Brendan Gleeson, who plays the film’s other main character – an aging, would-be songwriter – is himself a fiddle player, and his on-screen performances (especially in the local pub) provide plenty of Irish atmosphere.

Fact-based and historical dramas demand different musical approaches. One of the year’s most powerful scores was Terence Blanchard’s “The Woman King,” which employed a symphony orchestra, a choir of African-American opera singers and vocal solos by legendary jazz singer Dianne Reeves.

For this story of a 19th-century West African kingdom and its all-female army of warriors, director Gina Prince-Bythewood needed musical might as well, and the two-time Oscar nominee (“Da 5 Bloods,” “BlacKkKlansman”) and five-time Grammy winner supplied it with Reeves’ vocal improvisations, a trio of percussionists and the authentic rhythms and harmonies of West African music.

Similarly, Marcelo Zarvos’ music for “Emancipation” draws on wordless, African-inspired vocal sounds as well as Haitian musical instruments along with a dark orchestral foundation for its story of an escaped slave (Will Smith) eluding his pursuers in the forests and swamps of Civil War-era Louisiana.

And while we might not characterize the three-hour “Babylon” as historical drama, Damien Chazelle’s wild, debauchery-filled epic of 1920s Hollywood needed more than two hours of original music by his longtime collaborator, two-time Oscar winner Justin Hurwitz (“La La Land”).

He spent more than three years on the film, writing the aggressive, on-screen jazz-band material as well as the dramatic score (recorded by orchestras of up to 100 players) to echo the darker side of the Hollywood dream. Some of the music starts as on-screen source music but segues subtly into score during transitions from party scenes to action elsewhere.

For “Thirteen Lives,” about the rescue of boys and their coach from a flooded cave in Thailand four years ago, Benjamin Wallfisch recorded a small group of soloists in Bangkok for geographical flavor, but then processed them electronically, added the sound of oxygen canisters for percussion and rhythmic effects with a London chamber orchestra as a finishing touch.

Abel Korzeniowski eschewed the idea of musically characterizing the 1950s South for the tragic story of the lynching of a 14-year-old boy in “Till” — rather, he needed a traditional orchestra to stress the mother’s grief and her determination to call nationwide attention to the cause of civil rights. And Chanda Dancy’s score for the Korean War fighter-pilot film “Devotion” uses a choir, but only sparingly and subtly along with 100-piece orchestra to capture the intense emotions and heroism on display.

Composers often have the most fun with genre projects, whether fantasy, science fiction or comic-book heroes, and 2022 has seen plenty of those. Michael Giacchino’s dark, brooding score for “The Batman” was hugely popular with fans, suggesting the haunted figure behind the mask and the grim maelstrom of Gotham City crime. His two-hour-plus symphonic music also conveyed a sense of innocence for the tragic Riddler of the story; and intriguingly jazzy figures for the mysterious Catwoman.

The Oscar- and Emmy winner (“Up,” “Lost”) has become one of the most in-demand composers of recent years, and his track record includes some of the year’s biggest box-office successes (among them “Jurassic World: Dominion” and “Spider-Man: No Way Home”).

Ludwig Göransson, who won a 2018 Oscar for his massive, African-music-influenced “Black Panther” score, managed to top himself with an almost entirely new score for “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.” He first traveled to Mexico in search of authentic-sounding Mayan culture sounds to represent Prince Namor and his undersea kingdom of Talokan.

He also flew to Nigeria to find and record African musicians, singers and rappers. He combined recordings made in both locations (including such evocative sounds as the harp-like kora) with an 80-piece London orchestra, 40-voice choirs in both London and Los Angeles, plus another 20-voice ensemble that specialized in Mesoamerican music. The vocally driven score took a year and an estimated 250 musicians and singers to accomplish.

Guillermo del Toro’s “Pinocchio” demanded something altogether different. Working again with French composer Alexandre Desplat – two-time Oscar winner including “The Shape of Water,” del Toro’s previous film – he co-wrote several songs and inspired a score that ranged from charm and innocence for the title character to dark martial figures representing the 1930s Italy of Mussolini.

Desplat’s unique approach for this stop-motion animation film about a wooden puppet was to create an orchestra consisting almost entirely of wood instruments: strings, woodwinds and percussion, including mandolin, recorder and accordion for appropriate Italian flavors. Only the glass harmonica and Crystal Baschet for the Blue Fairy deviated from that rule.

Michael Abels’ “Nope,” his third film for Jordan Peele, is his most ambitious yet, combining awe and wonder with mystery and horror in a story of L.A. siblings terrorized by a malevolent UFO; he needed a 75-piece orchestra and 32-voice choir for the most dramatic moments.

Four-time Oscar nominee Danny Elfman (“Milk,” “Big Fish”) also needed an orchestra and choir to score Noah Baumbach’s quirky “White Noise,” supplying touches of musical irony for a story about a college professor and his family’s response to the arrival of a toxic cloud over their town.

Nathan Johnson reunites with cousin Rian Johnson for “Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery,” using a 70-piece orchestra to provide clues for the whodunit; Daniel Craig’s Benoit Blanc motif returns, along with new themes of extravagance and opulence.

Some music remains a mystery at this writing. Yet to be unveiled are Simon Franglen’s score for James Cameron’s sci-fi epic “Avatar: The Way of Water,” said to feature exotic sounds from across the globe as well as choirs from London and the Pacific islands; and Thomas Newman’s music for “A Man Called Otto,” Marc Forster’s comedy-drama about a man whose attempts at suicide are constantly thwarted. Neither should be counted out as preliminary voting for the shortlist begins Dec. 12.

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.