Oscar-Contending Documentary ‘Riotsville, U.S.A.’ Breaks Down Late ‘60s Program To Suppress Urban Unrest, Which Echoes Today

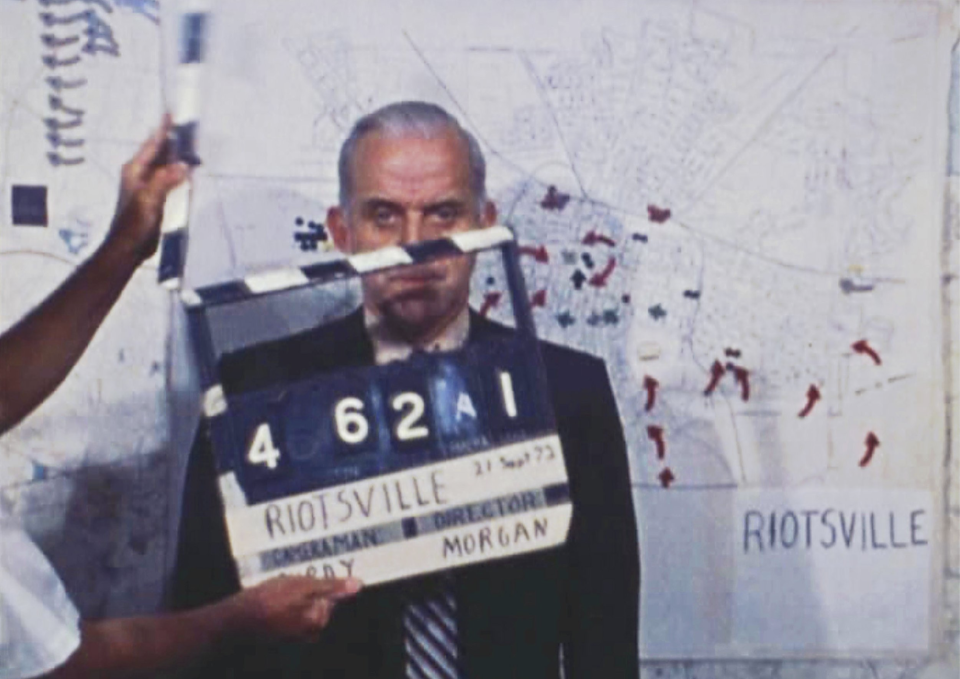

A phony pawn shop. A fake liquor store. A village made up of one faux storefront after another, like something from a Hollywood backlot. What was this strange, ersatz Main Street erected on an army base in Virginia in 1967? A place dubbed “Riotsville.”

Contemporary America has forgotten about it, but decades ago the U.S. military assembled a mock town where law enforcement and military personnel could engage in a sort of pantomime – rehearsing how to successfully suppress an urban riot. It wasn’t an abstract exercise. The training ground was constructed in direct response to revolts that had erupted in the Watts section of Los Angeles in 1965, and two years later in Newark and Detroit.

More from Deadline

The new documentary Riotsville, U.S.A., directed by Sierra Pettengill and written by Tobi Haslett, explores the building of this imitation urban flashpoint and what it says about this country’s intransigent response to anything that threatens the status quo – that is to say, a well-ordered society ruled by whites.

“[Riotsville] was built as part of the Civil Disturbance Orientation Course, which the military called CDOC for short,” Pettengill explains, “that brought in police officers, governors, military brass, the FBI, Secret Service, and a lot of local rank-and-file police officers to be trained. They basically did a ‘reenactment’ — used loosely — because they were fictionalizing a typical way a riot would unfold.”

Riotsville, U.S.A., from Magnolia Pictures, is now playing in Los Angeles and other cities. Pettengill made the film entirely out of broadcast news footage from the era and archival material shot by the U.S. military. The “cast” of these performances consisted of soldiers in uniform and other soldiers outfitted in civilian attire, playing “rioters.”

“The Riotsville recreations start with an instance of police brutality,” Pettengill notes, “and then document the sort of reaction from the citizens of the fake city Riotsville to that.”

Incisive narration written by Haslett provides a deeper examination of the context of these Riotsville reenactments. They were performed at a time when large scale uprisings against injustice had caused some to question structural inequality and others to man the barricades.

“A door swung open in the late ‘60s,” the narrator says. “Nothing that big or bright had ever happened in so many American cities. And someone, something, sprang up and slammed it shut.”

The challenge for Haslett as writer and the filmmaking team, he tells Deadline, “was to basically turn those clumps of thematically specific montages made from archival footage into an argument about the period, about the history of policing, and also about some of the deeper political and social problems that were revealed by the Riotsvilles and the social response to the riots. So, what are police for? What is the relation between the security apparatus and redistribution?”

The documentary reveals the Riotsvilles were the unintended result of a commission formed by President Johnson in 1967 to study the causes of the civil unrest in Newark, Detroit and elsewhere. The 12-person entity, which came to be known as the Kerner Commission, was stacked mostly with moderate white political figures, but against all odds it came out with a substantive report that attributed the uprisings to the effects of white racism. To address the root causes of urban uprisings the commission called for more equitable distribution of wealth, guaranteed minimum income, robust jobs and housing programs, and improved schools.

“What white Americans have never fully understood — but what the Negro can never forget — is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto,” the report said. “White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

Tucked into the report was an addendum about funding efforts to suppress any future revolts. In the end Congress poured money into that and that alone. It ignored the commission’s plea to avert future uprisings by investing in a more just society. The political winds quickly shifted from an earnest inquiry into the conditions of urban life to an embrace of “law and order.” Congress sent billions to police to buy anti-riot gear, and poured additional sums into the creation of the Riotsvilles.

“I feel like the footage and by necessity the film itself kind of takes place at three different levels. There’s the footage of Riotsville, which is the demonstration of the elaboration of a specific tactic — the specific techniques and tactics of riot control,” Haslett says. “At a somewhat higher level of abstraction there’s not tactics, but strategy. The tactics are part of a larger strategy, which is containment and control. You see that, too, in the kind of discussions of why it’s important to impose law and order.”

Haslett continues, “At the highest level of abstraction is the overall drive or desire and the entire kind of edifice that we’re looking at — and that’s embodied by the news camera footage — for the society to reproduce itself with as little friction as possible, despite the fact that the society’s main driving force is the production of inequalities that make that kind of friction… inevitable.”

A fateful, and often fatal, paradox.

It didn’t take long for the scenarios war-gamed in the original Riotsville to be put to use. The Kerner Commission had warned against “over-preparing” for possible unrest in the summer of ’68. But when protests by Black and white demonstrators broke out at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the resulting violent response by law enforcement was later deemed a police riot.

Chicago has received inordinate attention in popular culture, but the filmmakers train their attention on the overlooked Republican National Convention, which took place that summer in Miami Beach. Richard Nixon, running on a law and order platform, was nominated for president, with Spiro Agnew as his running mate.

“We’ve heard about Chicago,” the narration (voiced by Charlene Modeste) intones. “But we’ve been living through Miami Beach.”

The RNC choked off access to their event by holding it in an enclave accessible only by causeways. When protests timed to the RNC took place in the majority-Black neighborhood of Liberty City, the national news media, gathered en masse for the RNC, mostly ignored them. Violence erupted after a white man drove into Liberty City in a car bearing a “George Wallace for President” bumper sticker and police cracked down. Network news crews did capture a bit of that.

“It’s what’s covered and what’s not covered,” Pettengill says. “The many days of people organizing [in Liberty City] is not a single image that is economical in the same way that a burning cop car is. But they tell you very different stories about what’s happening.”

Riotsville, U.S.A. does not stray from that time period, but there are clearly parallels to today for anyone who cares to make the connection. The widespread upheaval following the police murder of George Floyd led to another “societal reckoning” with system racism and injustice. Calls to reevaluate funding of police and militarization of police forces were debated, but what has been the result? A return to the crouch of “law and order.”

Similarly, in 1967 President Johnson was convinced “outside agitators” were responsible for stoking unrest in urban centers, apparently unwilling to believe it could have arisen organically within communities oppressed by racism, over-policing, poor housing, limited economic opportunities and the like. Flash forward to 2020 when upholders of the status quo pointed a finger of blame at “Antifa” for fomenting unrest.

“It is interesting how the outside agitator myth repeated itself,” Haslett comments, “but I think at a certain point in the course of the George Floyd uprising, it reached its own kind of internal limit, because it was so clearly inadequate to explain just the magnitude of what happened in 2020.”

Riotsville, U.S.A. speaks to today in another respect. Pettengill points out that while we have forgotten about the Riotsvilles of yesteryear, a modern corollary persists.

“These kinds of [Riotsvilles] still exist and are being constructed today,” Pettengill says. “If you Google ‘tactical scenario village,’ and ‘police,’ they’re just endless. There’s one being built in Chicago right now and one in Atlanta that has a really vibrant protest movement opposing it.”

Best of Deadline

James Bond Movies In Order: Filmography, Bond Women & Iconic Villains

The Royals And Politicians Of 'The Crown' And The Actors Who Play Them — Photo Gallery

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.