Original ‘Mario’ Creator and Composer Unlock ‘The Super Mario Bros. Movie’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

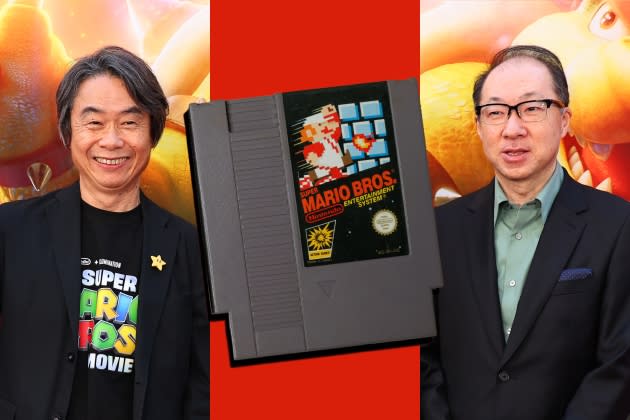

It’s been over forty years since Mario made his video game debut as the hero of 1981’s arcade classic Donkey Kong, although back then he was simply known as “Jumpman.” He’s had quite the glow up since then, appearing in over 200 video games, a Saturday morning cartoon, and now two theatrically released movies. And the success of Donkey Kong didn’t give the world just one star, it also delivered another: creator Shigeru Miyamoto.

Credited as the brains behind not just Mario, but Zelda, Star Fox, Pikmin and more, Miyamoto has been the creative and philosophical force driving Nintendo for decades, having reached a level of icon status in the games industry few can rival. But he didn’t do it alone. Beginning with 1985’s Super Mario Bros., Miyamoto began collaborating with composer Koji Kondo, whose keyboard arrangement for the game would become a master class in elegant simplicity, worming its way into players’ heads for generations.

More from Rolling Stone

‘The Super Mario Bros. Movie’ Is Not Ruined by Chris Pratt’s Mario

Original ‘Tetris’ Creators Reveal the Game’s Wild Espionage Origin Story

‘Kirby’s Return to Dream Land Deluxe’ Review: A Candy-Coated Balm for the Soul

Related

‘The Super Mario Bros. Movie’ Is Not Ruined by Chris Pratt’s Mario

Original ‘Tetris’ Creators Reveal the Game’s Wild Espionage Origin Story

‘Kirby's Return to Dream Land Deluxe’ Review: A Candy-Coated Balm for the Soul

The most obvious industry parallels for the two might be Walt Disney (Miyamoto) and John Williams (Kondo). The former pioneered both game design and art direction that arguably saved the entire medium. The latter breathed life into virtual worlds with melodies as addictive as the gameplay itself. Together, they built the legacy of Nintendo with some of pop culture’s most memorable characters and music.

Now, they’re working to bring that legacy to a whole new generation, as well as audiences who may never pick up a controller. A joint production between Illumination and Nintendo, The Super Mario Bros. Movie feels like a labor of love in just about every way, and much of that is due to the creative input of Miyamoto and Kondo. Miyamoto, bringing his stewardship of the brand to the film in the same way he did to the recently opened theme park, worked with the creative team at Illumination to find the right angle to power-up Mario for the silver screen. Kondo, working with composer Brian Tyler, provided his expertise and nearly four decades worth of arrangements that informed the film’s score.

Following the film’s LA premiere, Rolling Stone met with the duo to discuss the difficulties of adapting their work, Bowser’s fingers fitting into piano keys, and how sometimes success can actually be a curse.

Why is now the right time for Mario to make the leap into film?

Miyamoto: So, about 10 years ago — up until that point Mario was created specifically for a video game. And we had created Mario as a character to be used in video games as we make new ones. And because of that reason, we didn’t set any outside details that are unnecessary for the game, because it could turn into limitations in the future. [So] things like, “What’s Mario’s favorite food?” “Does Mario have a brother?” “Does Mario have a sister?” All those kinds of questions were unnecessary. We didn’t do that. But when it comes to movies, [that kind of] peripheral information and detail becomes important, it becomes crucial. So that’s something that we had to kind of grapple with.

And about 10 years ago, after this time period where [people were saying], “It’s either Nintendo, Sega, Sony or Microsoft,” after all of that ended, we started to want to focus on the idea of wanting people to enjoy Nintendo and love Nintendo as Nintendo, not specifically as any certain game. And alongside Mr. Iwata, we decided that we wanted to shift focus and take a more IP-focused approach. And within that kind of approach was the idea of creating movies, theme parks, and other things like that.

Why was illumination the right partner to help bring this to life?

Miyamoto: After that decision to take the more IP-focused approach, we had talked about potential partners, and then our encounter with Chris [Meledandri] was an interesting one in that, as we got to know each other, we realized that our philosophies and the way we think about creating something new is very similar. We thought that this would be a great match and decided, let’s work together to create something new. And it was just this kind of joint forces of these two different creatives, and then we finally decided on creating a new movie and since then, it’s been a smooth sailing process from there.

There were times when people would come to the original creators, Nintendo, and say, “Here’s the kind of movie you want to make. And here’s how we can expand this into business.” And it was back in that time when we changed approaches that we started to feel like it should be Nintendo that creates this kind of thing. With Chris it wasn’t, “Hey, let’s make a Mario movie.” It was like, “Let’s create something new,” and that kind of shift in perspective and how our approach to creating something was what really made this partnership work.

Kondo-San, what was your experience like collaborating with composer Brian Tyler on the music for the film?

Kondo: The overall film, of course, from beginning to end, was composed by Brian [Tyler]. We really wanted him to take control of that process. My contribution for him was to provide game music that I thought — a list of game music — that would match with the different scenes that I had seen in the movie. And then Brian took some of those suggestions. And then he added different phrases of music. He took those and added those phrases to the overall score, rearranged things in ways that supported the overall film.

I didn’t provide specific instructions to say, “Please use this music in this scene.” And the reason for that is, I didn’t want people to be taken out of the movie by hearing a piece of game music that didn’t fully fit that particular scene. So they were really just suggestions as to what I thought would help, and then Brian was able to take that again and weave that into the overall composition for each scene. And again, he just came up with this really amazing piece of work.

There’s a fine balance between music composed for the film and needle drops with popular songs. What went into striking that balance?

Kondo: As far as those outside pieces, those licensed pieces of music, I really think that’s up to the [directors]. And I think in this case, they did something that worked flawlessly within the overall structure of the film.

Are there tracks that you wish had made it into the film?

Kondo: No! I’d like to create the music myself! [Laughs]

Miyamoto: In the movie, there were temporary licensed [tracks] that were placed in. [We] then went in and tried to replace them with songs that were created specifically for the movie. But there were still scenes where we felt like the licensed songs worked better, and those are what’s left in. Another thing that we thought about was [that] all of the music created for the movie — that includes Nintendo music — none of it has lyrics and vocals, and having a movie score that doesn’t have any lyrics and vocals might be a little off, so we thought it’d be good to have. We’ve kind of leaned on the licensed music to provide vocal lyrical relief in the musical score.

To that point, was there any internal debate about the decision to bring back “The Plumber Rap” or “The DK Rap?”

Miyamoto: This is actually something that was decided early on by both the screenplay writer and the director that they wanted in there. And on our part, there was a lot of nostalgia, as we did some of that PR work in New York [to dig up those tracks] so I think it was a pretty unanimous decision.

There’s a scene early on in the film that replicates the side-scrolling nature of a traditional Mario game. What were the challenges of bringing the visual language of a video game to the screen?

Miyamoto: [When] we’re talking about Mario games, there’s the experience of playing a Mario game and I think there’s a lot of hardship. We initially encountered a lot of difficulty trying to take that abstract idea of what an action Mario game is like, and then recreating that visually was something that we grappled with. And it was difficult. But as we’re trying to work on the movie, we were able to make a select few scenes that really kind of capture that. Like you were mentioning, the early scene where they’re running down the street, or even that course that looks like it’s been made from Mario Maker, things like that. And as we’re kind of finalizing those scenes, it really dawned on us that even if we just use things that seem and look familiar to people who have played the games, like the assets and whatnot, we were able to create something that was convincing and felt good, and I think after that it became a lot easier to handle and much easier to think about.

In the film, Bowser is portrayed [by Jack Black] as having a bit of a Neil Diamond-esque, tortured-soul vibe. If the video game iteration of Bowser were a musician, what kind would he be?

Kondo: I really think that Bowser is a multi-layered character depending on the game in which we’re getting him [or] we’re talking about, so I think he would really be in tune [no pun intended] with the game itself.

Miyamoto: Talking about the fact that Bowser himself plays the piano was an important factor in that when the idea came up about Bowser playing the piano, we were thinking, “How big is the piano have to be to have his fit? Are his hands gonna get caught in the keys? Is he going to be able to hit the right keys?” All of this doubt and question came up, however, just the image of Bowser sitting in front of the piano was really what did it for us.

One of the most surprising additions to the film is the fact that Mario and Luigi have this very fully development family. What was the approach to introducing those characters?

Miyamoto: I mentioned, we [actively tried] not to add any unnecessary details for the video games. But you know, the fact that there are other Italian immigrants living in Brooklyn, living in the same household as a family – with an at-home, family feel — we thought this was very important. And about 20 years ago, there’s an illustrator named Mr. [Yōichi] Kotabe, who had illustrated a diagram of the family of Mario and Luigi. So that’’s what we based it on. And Illumination then took that and added their kind of flavor and touch to it.

As for Mario’s mom and dad, those were based on some old, old illustrations that we had. Once that was set, it was really thinking about, “How do the brothers fit within their family? And what Mario’s relationship is with his dad and his mother?” Then through that, it [kind of] impacted what Cranky Kong’s relationship was going to be with Donkey Kong. [We also] had this rich couple, Francis the Dog’s mom and dad. Pauline was also there, but you know, some of the characters that appear on TV, those are probably the only “new” characters that we created. Everything else was created with what we already had.

Mario’s been around for over 40 years and the movie has references to everything including Spike from Wrecking Crew to Lumas from Super Mario Galaxy. How did you decide what eras of Mario history to pull from for inspiration?

Miyamoto: So first of all, in terms of characters, we were very fortunate in the fact that the directors from Illumination, the writer, basically the entire staff was so well-versed and loved Mario. Actually, they probably know more about it than I do. It was really a process of people dropping in assets like this or making the request: “Do you have any assets that are about this thing that I want to reference?” Things like that. So it’s a combination of the 40 years’ worth of content that we’ve had, coupled with this team of, basically, fans that want to make this, so the only trouble was trying to have to sort through all of that.

You were mentioning Spike from Wrecking Crew. That idea came up and we thought, “Oh, that could be fun. It’d be a lot of fun to see that.” Another example, I was thinking that we need to place Donkey Kong somewhere in New York, but the idea of placing Donkey Kong in his world, in the Mushroom Kingdom, was kind of a big step — and adventurous step — that we couldn’t have thought of.

And when we’re talking about Easter eggs, there are just countless of them. I think you’ll need to watch it more than five times. Five times is probably not gonna be enough for all of it.

Kondo: There’s a ton of sound effects, and not just sound effects within [the film world] but integrated into the music.

Miyamoto: I think we provided probably over a hundred sound effects to the team. So even Mario’s jumping sound, in the Japanese version, there’s a different voice for every single “Wahoo!” In the game, it’s usually the same voice. So we had a lot of fun doing all of that.

Kondo: I think it’d be interesting to see how many people catch that when Luigi receives a phone call, the ringtone… I don’t know if you noticed that. That’s the power-up [sound effect] for the GameCube.

We’re at a time in popular culture when video game adaptations in film and television are hitting their stride. What are your thoughts on that trend and what’s Nintendo’s place in it?

Miyamoto: I think [that] Nintendo, once it becomes popular, always wants to do something different. So, I’m hoping it doesn’t become as popular! [Laughs]. Because we really want to focus on our work on [this one] movie for the moment.

So, now Mario’s a movie star. Bowser’s a rock star. Are they ready for their Rolling Stone cover?

Miyamoto: Please, by all means. We’d love it!

Best of Rolling Stone