How ‘Oppenheimer’ Production and Costume Designers Brought Christopher Nolan’s Vision to the Screen

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Production designer Ruth De Jong and costume designer Ellen Mirojnick have worked on projects helmed by incredible filmmakers. De Jong earned an Emmy nomination for David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return and worked as the production designer on Jordan Peele’s Us and Nope. Mirojnick, meanwhile, earned an Emmy for Behind the Candelabra — one of her six collaborations with Steven Soderbergh — and designed costumes for Steven Spielberg (Always), Richard Attenborough (Chaplin), Kathryn Bigelow (Strange Days), Oliver Stone (Wall Street) and Paul Verhoeven (Basic Instinct, Showgirls and Starship Troopers).

So the pair know a thing or two about what makes a great director. But it’s Oppenheimer writer-director Christopher Nolan whom De Jong and Mirojnick call the ultimate filmmaker.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor on Why She Had to Be Uncomfortable for Ava DuVernay's 'Origin'

The Making of 'The Holdovers': "Depressing Sh** Can Still Feel Cozy"

'Oppenheimer' Leads Feature Noms of MPSE Sound Editors Golden Reel Awards

“There is no other director like him, and I’ve worked with some of the best,” says Mirojnick. “His method of collaboration is very generous, and he shares a massive amount by comparison to anyone else.”

De Jong and Mirojnick recall first receiving Nolan’s 180-page script, based on the J. Robert Oppenheimer biography American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. It came with a treasure trove of images the director had assembled of Oppenheimer, his associates and Los Alamos, the New Mexico town where much of the film would be set. For De Jong, the work began when she broke down the script scene by scene, location by location with a researcher, covering their department house with historical images.

“You should have seen this house, papered from floor to ceiling,” says Mirojnick, who adds that it was the first step in entering Oppenheimer. But a historical reenactment was, according to both designers, absolutely what Nolan wanted to avoid in the film’s visual vocabulary. Capturing the essence of the real Oppenheimer’s world was the goal for the film, which would be told largely through the scientist’s own, subjective perspective.

Oppenheimer’s centerpiece is Los Alamos, the isolated location for the Manhattan Project. The production did not have the same resources — or time — as the U.S. government did in building the site, which housed the project’s scientists and their families. But filming exteriors in the real Los Alamos was impossible — De Jong notes the presence of a Starbucks and stucco strip malls. The production designer ended up constructing dozens of buildings in a smaller-scale version of the town, which also housed the various department offices as if it were a studio lot in the middle of the desert.

The isolation worked in the production’s favor. “Chris and I wanted the ranch to be 100 percent period,” says De Jong. “There were no crew vehicles. Vans would drop people off in the morning and pick them up in the evening. No tents, no video village, nothing. The actors would leave their hotel and lose cellphone service immediately. Every day, you were just there in it. There were no distractions.”

That period authenticity was not a requirement, however, across the entire film. “We used the word ‘regeneration,’ ” says De Jong of the way the film transports the viewer into Oppenheimer’s life. “The research was essentially a launchpad to take us into that place.”

For Mirojnick, that involved streamlining Oppenheimer’s wardrobe across the decade-spanning film. “I thought I was making a period film. That wasn’t the case,” she says. “Chris had a vision, and he wanted to make a film that wasn’t stylized or precious.”

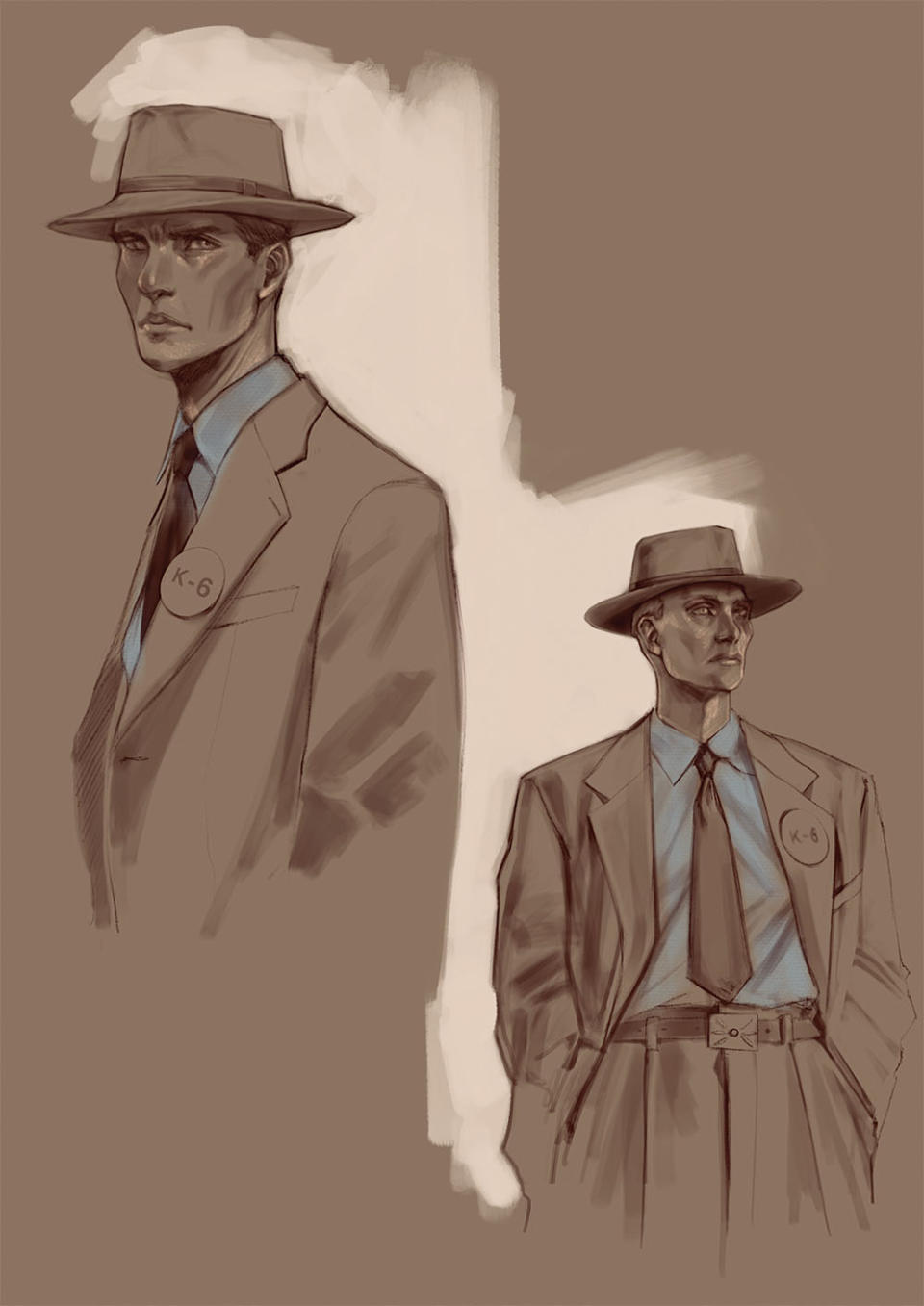

Two of Nolan’s directives in particular surprised Mirojnick from the onset. “He said two things: ‘I don’t want anyone to wear hats except Oppenheimer, and I think he only needs four suits,’ ” she recalls, noting that the latter seemed “crazy over five decades.” But as the project progressed, it all made sense. “Because of how Chris tells stories, each and every decade needed to be dissected, and the essence of each decade needed to be extracted. The overall effect would be to move between periods without any dates in front of you, but you would always have the sense of moving through time,” she says. “It was freeing, frankly, to design characters in a way that they felt authentic to who they were and real to the story we were telling.”

For the look of the title character, Mirojnick recalls the first fitting with star Cillian Murphy in which she constructed a suit with little notice while the actor was briefly in Los Angeles. “Cillian was my sketch[pad]. He was three-dimensional,” she says, adding that Nolan was present for every fitting — a rarity for a director. “Chris is a collaborator who actually participates with you on every level. You see the film [being made] right in front of your eyes.”

This story first appeared in a January standalone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter