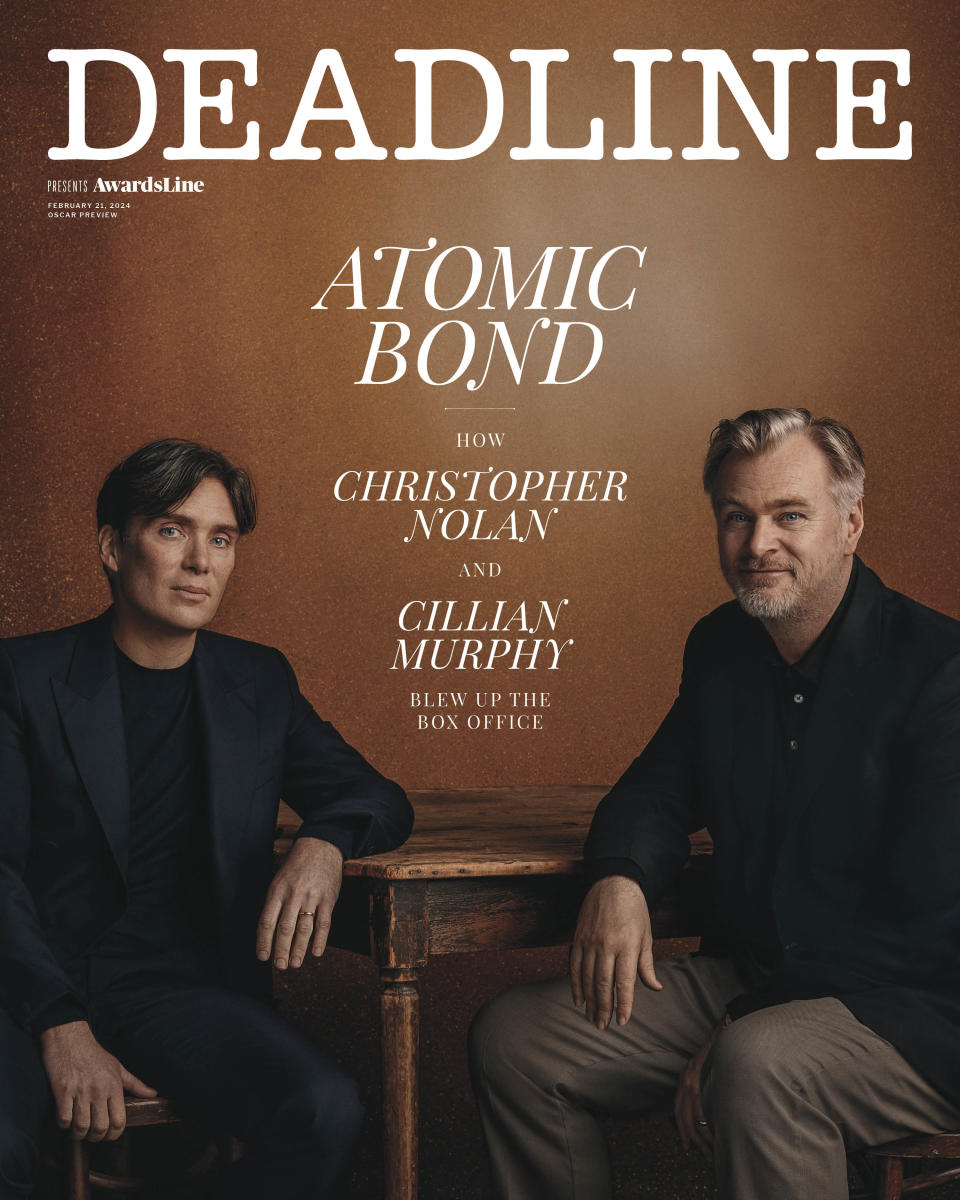

‘Oppenheimer’ Director Christopher Nolan And Star Cillian Murphy On The Slow Fuse That Led To Their Big Bang At The Box Office

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In some ways, Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan’s biggest non-superhero movie, was a product of the pandemic. Until the winter of 2020, the director had been loyal to Warner Bros., and their logo was to be found on every film that Nolan either wrote, directed or produced.

While he was never formally tethered to that studio, Nolan had been monogamous as its cornerstone tentpole filmmaker, ever since his 1999 breakout indie film Memento led him to create Insomnia there.

More from Deadline

That year, however, everything changed. The usually mild-mannered director was outraged by the decision of former WarnerMedia CEO Jason Kilar to perpetrate a blindside dumping of the studio’s entire slate onto its HBO Max streaming service. This attempt to build subscribers for its streaming service at a time few were going to theaters incensed Nolan and many others. The filmmaker was still wounded by the studio’s decision to release Tenet while the world had yet to fully emerge from lockdown.

In fact, he didn’t even have a film in the bunch being dumped, but he was nevertheless upset to see films made for the big screen — like Dune, The Matrix Resurrections, Wonder Woman 1984 and future Oscar-winner King Richard — drop day and date. As much a warrior for the traditional theatrical experience as Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino, Nolan decided he would look elsewhere; no idle threat when you consider that the movies he directed there grossed north of $6 billion (more when you consider the DC films he produced or godfathered).

When Deadline revealed that Nolan would make Oppenheimer, and that Cillian Murphy — still riding high on the success of showrunner Steven Knight’s period gangster series Peaky Blinders — would likely play the title role, the news landed like a bombshell. Every studio responded by chasing it, and there were rumors that Warner Bros. might not even get a meeting. The lucky winner was Donna Langley, NBCUniversal Studio Group Chairman, who, like several other studios, agreed to Nolan’s ask for $100 million to make his movie, along with creative control and a massive global theatrical release.

“I’d wanted to be in business with Chris for a long time,” she says, “and he was always near the top of my blue-sky wishlist of directors. Just as movie fans, whose movies do we love? Chris’s name was always close to the top of that. And from a strategic standpoint, as we were coming out of the pandemic, it was very clear to us that the cinematic experience needed to be undeniable in order to get people back into movie theaters. Chris’s work is undeniably cinematic. He makes films for the audience to see in the movie theater. And so that became a strategic imperative for us.”

Her determination to land the project increased when she read the script. Juggling multiple timeframes, Oppenheimer explains how the work done by scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer in the early 1940s — the top-secret Manhattan Project, based in Los Alamos — led to the creation of the atomic bomb and the end of the Second World War. It also deals with Oppenheimer’s guilt, and how the American establishment turned on him once he’d served his purpose.

In there were two career roles, one for Irish actor Murphy as Oppenheimer, and another for Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss, the bureaucrat nominated to be Eisenhower’s Secretary of Commerce. Strauss was so insecure about being snubbed by Oppenheimer, Einstein and other geniuses while a member of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission that he would try to play silent assassin to Oppenheimer’s reputation by staging a controversial hearing to revoke his security clearance and render him a pariah.

“I was just transported by it,” Langley says. “I was so relieved that it wasn’t a mind-bending, twisty-turny, science fiction extravaganza that I needed an encyclopedia to understand. This was a story about a living person and a moment of time and history. It’s one of the best screenplays I’ve read in my career.”

It was a script with all the trappings of a Christopher Nolan movie — shifting timeframes, complex characters — and it had an emotional core that struck Langley deeply. “It’s very intimate on the one hand, but it also has a giant scope,” she notes. “The world is on the point of collapse, there’s technology and innovation being chased after by multiple countries, and America has to be first in the race to get there. At the time, being deep into the Ukraine war, I was really struck by how resonant and relevant the story was. And as Chris put it to me, ‘This is the greatest American story never told in cinema.’”

Kilar is long gone now, and Warner Bros. is a more theatrical-friendly place, as theatrical has become the priority for event films once again. Nolan won’t say whether this was a one-time fling, but it is hard to deny he saved his best film for Universal. Unusually for a three-hour, non-franchise film released in July, it has made a near-billion-dollar gross, won seven awards at the BAFTAs (including Best Film and Best Director), and is widely believed to be the Oscar favorite, receiving 13 Oscar nominations that put the film in the frame for the same key categories, while recognizing Murphy, Downey Jr. and Emily Blunt for their work in the acting categories.

Nolan vividly remembers the time first he ever saw Murphy: it was a photograph in a newspaper, probably the San Francisco Chronicle. The director was staying in a hotel in the Bay Area, writing and rewriting the script for Batman Begins, while at the same time scheduling screen tests for the lead role. At the time, he didn’t know who was going to play Batman. He was, he says, “just looking to see who was out there.”

What caught his eye was an image from Danny Boyle’s apocalyptic zombie thriller 28 Days Later: though Murphy was covered in blood, the actor’s bright blue eyes provided stark contrast to the bleakness of a new reality spent eluding flesh-eaters. “It was a cool photo,” says Nolan, turning to Murphy. “You could see your eyes, and your presence. I was just very struck by it.”

“Had you seen the movie then?” asks Murphy.

“No,” says Nolan. “I literally just saw a picture. I then watched the movie, but the truth is, I already was interested. These things are very instinctive, and that’s the relationship that an audience has with an actor as well. It’s an instinctive and instant connection. So, yeah, love at first sight. I see the picture and I’m like, ‘Man, that guy’s got something.’”

Nolan invited him to LA for a meeting. They met, connected, and suddenly Murphy was on the Caped Crusader shortlist of actors Nolan tested for the role that ultimately went to Christian Bale. “But I think at the time you were quite a bit… more slight than you are now,” recalls Nolan. “You walked in, and I remember thinking, ‘Are you really going to be able to be Batman?’”

Still, Nolan was interested to see what Murphy was capable of, shooting a screentest with the actor reading some of Bruce Wayne’s scenes. He shot them in 35mm on a Warners soundstage with full, professional lighting — “Because I really wanted the studio to really be able to see what this was going to be” — and the results surprised him. “I just remember a sort of ripple of excitement going through the crew,” he says. “Hollywood crews, particularly, they’re very professional, but quite jaded. They’ve seen a lot of stuff, so you don’t often get that kind of thing where you feel everyone is paying attention.”

Murphy wasn’t expecting to get the part. “I remember knowing it was a test,” he says. “From my point of view, I was already a fan of Chris’s work and I just wanted to get in the room and audition. That would have been enough. I was totally content at that stage of my career just to say, ‘Oh man, I was in a room with Christopher Nolan, and we worked on some scenes.’ And then he called me out of the blue. I did not expect him to say, ‘Well, how about this other part?’”

That other part was the film’s main villain, the Scarecrow, which marked a significant shift in the Batman franchise. “I don’t remember having any resistance whatsoever to having a relative unknown take on a big part like that,” Nolan says. “And previously all those villains were played by actors like Arnold Schwarzenegger or Jack Nicholson. They were the biggest stars in the films. But no, [the studio] got it. They were all blown away by the test.”

So, what made him right for the villain but not Batman? “I don’t think he had the physicality at the time,” says Nolan. “We tested everyone as Bruce Wayne and we tested them as Batman, and the thing that Christian had that was so striking was that he understood that so much of acting is about reality. So much of acting is about emotional truth. And when you put on a costume like the Batsuit, you have to become this icon. Christian had this crazy energy that he just directed. He’d figured out how that worked and what that would be — the way Bruce Wayne does in the film. He adopts this persona. It’s a very specific thing. And he tore a hole on the screen as Batman. It was like, there was no question.”

Nolan turns to Murphy. “But it was interesting watching Peaky Blinders years later and seeing you play Tommy Shelby,” he says. “Whatever it is we’re talking about here, you’d figured it out. That’s an iconic character with an oppressive presence, where he walks into the room, and everything goes quiet, and he owns that space. In the way Batman does, or an iconic character of that kind. There’s a physicality that’s extremely confident and strong in everything he does, in every gesture.” He pauses. “Is that a conscious thing you’ve developed over the years, or was it just looking at that part and thinking, ‘How do I do that?’”

“I think it was both,” says Murphy. “But I also think I felt, back then, that that was a part I hadn’t really explored before, that kind of physically imposing character. I’d never been offered those parts. But I always think, Chris, that one of your underrated strengths is casting. Everyone knows all of your amazing strengths, but you cast things exquisitely. And I think the Scarecrow was the right part for me to be in at that time in my career.”

So, what makes an actor right for the type of role he was wrong for earlier? “I’ll tell you a story,” says Nolan. “I was talking to one of the crew, Nathan Crowley, who designed the Batman films. He told me he had seen Peaky Blinders. I hadn’t. And he said to me, ‘Yeah, Cillian put on all this weight for the part. He’s big.’ I watch it, and I’m like, ‘That’s not what it is, it’s not that.’ I mean, maybe he did put some bulk on, maybe he’s just getting older and more filled out. But that’s not what I saw. I was like, ‘No, this is physically the same guy, but he is using his gift, his instrument, to project scale in a way that I hadn’t seen before.’”

While it took him time to summon that presence, Murphy agrees that it had more to do with craft than physical bulk. “When I was a kid, about 16, I had the great privilege of seeing Jonathan Pryce play Macbeth at the National Theatre in London,” he says. “I had only seen him in films like Brazil, and he was a fairly slight guy. I watched him in real life play this huge role and he just seemed like this enormous force. It was about projecting.”

“I don’t know how you do that,” says Nolan. “And it’s probably something you don’t like to be too self-conscious about, but what I saw you do, what Tommy showed me, that’s what I saw, was an ability to transcend your own physicality, your body, and work beyond that and make people see this character in a different way. I mean, that’s the gift of great actors. And I don’t know how it works, but I’ve seen it.”

“I don’t know what it is either,” says Murphy.

Whatever that elusive quality was, Nolan knew he needed it to tell the story of Robert Oppenheimer. From his feature-length debut, the sleight-of-hand thriller Memento, to the Dark Knight Trilogy, and the boundary-bending likes of Inception, Interstellar and Tenet, Nolan has always been unafraid to tackle ambitious and complex narratives. But framing Oppenheimer’s story was to be the biggest challenge of his career.

Nolan grew up in the U.K. in the 1980s, during the Cold War and the continued concern over the danger of the arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. His curiosity about Oppenheimer began with a lyric in Sting’s 1985 song “Russians”, in the which the singer asks, “How can I save my little boy from Oppenheimer’s deadly toy?”

“I’m a little older than Cillian here, but he probably remembers growing up in the U.K. in the ’80s,” says Nolan. “It was a time of great fear of nuclear weapons. I talked to Steven Spielberg about this. It was like growing up in the ’60s, with the Cuban missile crisis. The ’80s were a very similar thing. There were protests, and there was a lot in the pop culture about nuclear weapons. But it was Sting’s song ‘Russians’ where I first heard Oppenheimer’s name, and there was this very palpable fear of nuclear Armageddon.”

The 2005 book American Prometheus, by Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin, captured Nolan’s interest further (in Greek mythology, Prometheus defied the Olympian gods by giving man the gift of fire). “It was after reading American Prometheus that I started to see a way in which you could tell this as a story, by taking on Oppenheimer and seeing it really from his point of view. And everything else followed after that. With something like the fear of nuclear weapons, you have to have a human way into that, and, for me, that was Oppenheimer.”

What struck Nolan in reading the book was hearing that Oppenheimer and his brother would go to Los Alamos as children to camp. “The connection between Los Alamos and the nuclear weapon he was developing, that comes from Oppenheimer’s childhood,” he notes. “He wanted to combine his interest in New Mexico — playing cowboy like he did, that love of the outdoors — with physics, and that’s what he did with the Manhattan Project.”

More so than the propulsive elements of the story, that the Americans were in a race against time to beat the Nazis, it was that element that convinced Nolan he, indeed, had a movie. “Once I’d read that, that’s where I started to see a personal connection,” he says. “And once you have the personal, then you start looking at the events, this thriller aspect to it that just kept coming in with everything that happened to Oppenheimer after 1945. It was a bunch of different things coming together.”

Indeed, Oppenheimer was later subjected to a politically charged tribunal that stripped his security clearance and rendered him a pariah, adding to his burden of having unleashed a weapon that, in the wrong hands, could destroy the world and had already cost over 100,000 lives when the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end WWII.

“American Prometheus is such a remarkable book,” Nolan muses. “Martin Sherwin worked on it for 20 years before Kai Bird joined. They did another five years. It’s a quarter of a century of research and interviews. I got the benefit of that, which was wonderful.”

Key to the story’s attraction was Oppenheimer himself, and Nolan was determined to unravel the scientist’s enigma. We’ve seen depictions of the fragility of genius in films like Shine, A Beautiful Mind, even Good Will Hunting, and how the brightest intellects can come unstuck. But Oppenheimer seemed to enjoy his post-WWII fame on the covers on Time and Life magazines, and in speeches. Was he a narcissist or a hero?

“I think he was definitely a hero, definitely a narcissist,” Nolan concludes. “He was a lot of different things. Very theatrical. What I got from American Prometheus, and what I started to get interested in is, he was someone who had a lot of neurosis and a lot of trouble very early in life, as he came of age at the same time that he was wrestling with these incredibly abstract concepts. We tried to fuse those things, show this kind of energy inside him and show how he masters that. And all the imagery of atoms and splitting atoms to me, they’re very related to his internal state, as a young man in particular. There’s a lot of dangerous tension inside this guy. A lot of dangerous mental energy.”

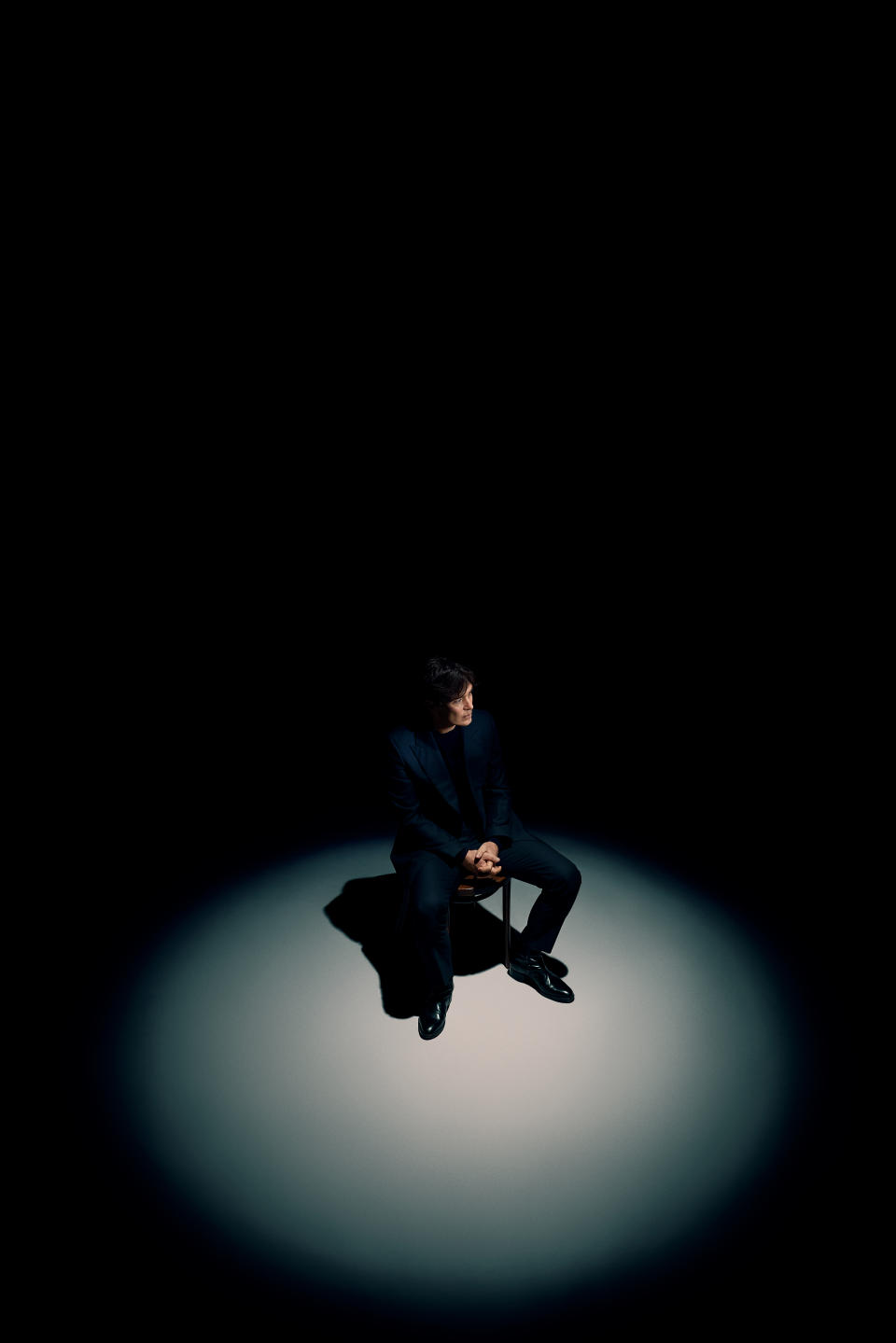

Murphy proved to be a strong physical match for Robert Oppenheimer; his handsome looks lent themselves to the theoretical physicist’s status as a womanizer, and those blue eyes were an ideal cipher for the wildness of those early scholarly years, when Oppenheimer was trying to harness his genius. All this came as a surprise to Murphy, back when Deadline revealed that Oppenheimer was Nolan’s next secret project and that he wanted Murphy to be number one on his call sheet, after five other movies with the director.

“I tried to ignore your story because I hadn’t heard from Chris or Emma [Thomas, Nolan’s partner and producer],” Murphy says. “It came out, everyone was texting me, and I said, ‘No, there must be some sort of mistake,’ or, ‘It’s just a rumor,’ because I hadn’t heard from those guys. A day or two later, Chris called me. This was out of the blue. Because Chris doesn’t write the script with actors in mind, which, when you think about it, is really, really smart because he doesn’t put any limitation on himself as a writer, or on the actor. So, it came out of the blue, and in the best way possible because I was unemployed. I hadn’t any work lined up.”

“It was perfect timing,” says Nolan. “He could have easily said, ‘Well, I’ve got a thing…’”

Murphy remembers that he had just finished up work on Peaky Blinders. “Bear in mind I said yes before I read the script,” he says, “because I always do that with Chris.”

Then it was Nolan’s turn to sweat, when he showed Murphy the script. “I said, ‘How about it?’ After Cillian said he was in, I flew to Dublin, and he came to my hotel and sat and read the script. I went off to the Hugh Lane Gallery and looked at Francis Bacon’s Studio, which I’d always wanted to see. And then we came back, and we had a chat about it. I remember doing this with Heath [Ledger] on The Dark Knight. He’d signed up for it, and then I showed him the script. There’s that moment of, like, ‘Are you going to feel good about that commitment?’”

He turns to Murphy. “But you seemed very into the script. You seemed very… I wouldn’t say relieved, I’d say you seemed excited.”

At this, Murphy breaks into a big smile. “It was one of the greatest scripts I’d ever read,” he says. “It was just astounding. But I knew it was huge. I knew this wasn’t just a part you could turn up at next week and get going. I was immediately going, ‘All right, f*ck, f*ck, f*ck. I’ve got to do all of this. This is huge.’ And, in fact, I was already working, getting going before I read the script. I knew I just had to go at it meticulously and make a strategy to go at it because there was just so much to do, emotionally, physically and intellectually.”

Murphy did more than just try on Oppenheimer’s signature hat. “I immediately started reducing calories,” he says, “which was a stupid thing to do, like, six months away from shooting. But I wanted to start feeling like him. I watched all the historical materials. I read the book, obviously. I started looking at all his lectures online. Any other stuff that was around. All the accounts from people that knew him were really, really interesting to me. Talking to [physicist] Kip Thorne, who was the scientific advisor on it. He had been lectured by Oppenheimer, which was really, really useful.”

Nolan interrupts. “That was a good thing,” he says, “because I’ve done a couple films with Kip; Interstellar was Kip’s original idea. I’d called him because I needed his help on the whole quantum physics thing. And in the course of the conversation, I realized that when he was at Princeton, he’d attended Oppenheimer’s lectures at the IAS. So immediately I was like, ‘Well, will you get on the phone with Cillian and talk to him about how he taught?’

Those testimonials helped Oppenheimer capture gestures and mannerisms that most of the audience for the film wouldn’t register.”

Says Murphy, “Kip talked about how Oppenheimer held his pipe on stage, and how he had the cigarette in one hand and the chalk in the other hand; We talked about how he was very aware of his presence, his legend, and his theatricality, all of that stuff.”

“I remember you telling me after you spoke to Kip, and we incorporated it into the staging as well,” says Nolan, “that Oppenheimer would let people talk. He was very good at summarizing a discussion. Which I think became absolutely key to the whole, to all of the Manhattan Project scenes.”

“He was an excellent synthesizer and manager,” Murphy agrees. “He didn’t seem the obvious choice for it, but he was.”

Together, Nolan and Murphy found the physical style for the lanky Oppenheimer, and one of the style influences was David Bowie, circa 1976. “Everything about him was constructed,” says Nolan. “Oppenheimer constructed his entire persona, his entire self. That’s why I threw the David Bowie photographs at you, Cillian. This was the Thin White Duke era. David Bowie has these crazy high-waisted trousers that were very, very similar in proportion to what Oppenheimer would wear at the end of Los Alamos. Bowie was always the ultimate self-constructed pop icon, and I think Oppenheimer was similar, in his own way. Obviously, it’s a completely different world, but he used his persona to achieve a mass of things.”

Murphy, who started out with the intention of a music career until he turned down a record deal and chose the acting life, sparked to the influence. “When Chris sent me that, I printed that picture out and I put it on my script,” Murphy says. “He sent it to me with no context, and I knew exactly what he meant, because I’m a music nerd and I could see the crossover. So, it was there in the back of my script for the whole shoot.”

More important, however, was getting Murphy ready for the emotional toll that playing Oppenheimer would bring, particularly after his triumph in Los Alamos. History hasn’t been kind to war heroes, as was seen when British mathematician/computer scientist Alan Turing cracked the Nazi enigma machine code — a breakthrough that shortened the Second World War — only to be punished for his homosexuality, which was illegal at the time. Similarly, Oppenheimer became a punching bag in a politically charged kangaroo court.

“I’m plagued by a line from The Dark Knight, and I’m plagued by it because I didn’t write it,” says Nolan. “My brother [Jonathan] wrote it. It kills me, because it’s the line that most resonates. And at the time, I didn’t even understand it. He says, ‘You either die a hero or you live long enough to become the villain.’ I read it in his draft, and I was like, ‘All right, I’ll keep it in there, but I don’t really know what it means. Is that really a thing?’ And then, over the years since that film’s come out, it just seems truer and truer. In this story, it’s absolutely that. Build them up, tear them down. It’s the way we treat people.”

Murphy believes that the security of 20 years working together emboldened him. “If you don’t have that history, or that level of trust, with a filmmaker,” he says, “I don’t know if you can be as brave or can dive in like I was able to on this one.”

Nolan has his own theory. “Maybe I’m wrong,” he says to Murphy, “but I feel like, after finishing Peaky Blinders, you were in a peculiar place in your career, because you’d been playing the same character for a lot of years. Very, very well with massive success, creative success and artistic success, and also people recognizing the success. You must have felt very comfortable in that character. Steven Knight’s writing is beautiful, and is always challenging the character, but it’s still a second skin that you’d developed that you were slipping into. But then you’re moving to an arena where all that’s gone. This was a true ‘out of the hot tub and into the cold plunge’ moment.”

Nolan appreciated the effort it took. “For me, particularly with such a big cast, Cillian was the element I was able to completely take for granted,” he says, “to the point where on Downey’s last day, he came up to me and said, ‘Do you understand how hard this guy is working for you?’ It was towards the end of the shoot. He was like, ‘He’s exhausted.’

And I said, ‘Thanks, Robert, he’ll be fine.’ And he was fine. But the point was taken that, yeah, I was able to take what he was doing on set for granted because I knew how great the work was. But the reality is, I didn’t realize the magnitude of the performance until I put it together in the edit suite. This is true, I think, of all great performances; you see what you see on set. But then, in the edit, you actually see it the way the actor has performed it. Even though you have been shooting in a crazy order, he’s figured out how all these pieces go together, and then you start to see it come together. It’s a really pretty magical thing.”

One of the first filmmakers Nolan showed the film to said something that really stuck with him. “There’s never that moment where you see the actor realize how great the part is,” he recalls this director telling him. Nolan knew exactly what he was talking about. “Because that’s the thing,” he says. “Particularly with serious movies, or when an actor has a great opportunity, you see them enjoying the taste of it a little too much. There’s always that moment. And that is not in this performance. This performance is totally pure. To me, this performance is much more about the real world, the way people are flawed, continuously flawed. There’s not one little thing they do wrong — we’re all good and bad, and there are layers of that. Oppenheimer is the absolute essence of that. The performance embraces that and carries the audience. But if the performance didn’t unselfconsciously embrace that, it wouldn’t work at all.”

Murphy is flattered. “It’s the nicest thing you could say,” he smiles. “But for me, I remember when I was doing it, if at any point I ever felt, I don’t know, anxious or insecure, I would always think, ‘No, Chris has seen something in me, and he’s drawing something in me out that I didn’t know was there really before.’ And I remember saying to him before we started shooting — because he’s always really pushed me in the best way, and he pushes all his performers in the best way — ‘Push me as hard as you possibly can on this one,’ because I knew we had to do that.”

The payoff comes in the ending, when the audience learns what Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) actually says to Oppenheimer. Strauss looks on, but Einstein walks past and ignores him. That Strauss was insecure and petty enough to believe their chat was about him, instead of being an intimate moment between geniuses who each bore the burden of creating weapons of mass destruction that pulled the world into a dangerous new age, is… Well, let Murphy describe it.

“I’m all about third acts and endings,” he says, “and when I read the script, that time in Dublin, knowing that’s one thing Chris always nails, I remember thinking, ‘What a f*cking ending.’ It’s extraordinary. And that’s from Chris’s imagination. It’s not from history, but it’s just genius. You can write an extraordinary script, but you can write yourself into a corner and the audience feels shortchanged if you don’t nail the f*cking ending.”

Says Nolan: “We talked very carefully about the moment where Kitty [Emily Blunt] says, ‘Did you think if you let them tar and feather you the world would forgive you? It won’t.’ I love the way Cillian performs in that moment, it was so important to me that it hit this exact note. And I didn’t know what that exact note was. I just knew that I’d know it when we hit it, because it needed to be sort of self-conscious in a slightly more open way.

“In the rest of the film, everything Oppenheimer does that’s a little bit vain or a little bit self-conscious, it’s almost as if he’s unaware of it,” Nolan says. “And I feel like in that moment, he opens up to the audience just a hair more, and says, ‘We’ll see.’ Because he puts the question to the audience, in a way. ‘Do you think the world will forgive you?’ ‘We’ll see.’ And I think the jury’s still out very much, but I think he’s definitely better thought of than he would be if he hadn’t been made to suffer.”

To Nolan, putting Oppenheimer, and Murphy, through the wringer in the latter part of the film evoked many higher themes. “When I showed it to Kai Bird for the first time, I said, ‘Look, this is my idea of who he is. This is who I feel he is. I feel that he’s ahead of those people in that room who are torturing him. I feel like he does have a vision to the world beyond that. And it’s partly a vision of fear, and a vision of the idea of the chain reaction. But it’s also partly how history will judge him. And if he fights too hard, or even if he won that fight…’

“It’s a bit Christ-like really, isn’t it?” he suggests. “It’s sort of knowing that the way to win is actually to lose. That was what I felt was inside him, and then the way you played it, Cillian. But there’s also great suffering. And I thought, I mean, Jason Clarke does such a wonderful job in the scene. And what nobody knows, because they weren’t there, but when we were filming your side, he just went nuts.”

Murphy interrupts. “Well, you f*cking made him go nuts! I thought at one point he was actually going to punch me out. It was like this big push in on me, each one, and I said to Chris, ‘I don’t know what you said to him, but he was like a f*cking animal, man.’ And then you used that take.”

Nolan lights up at the memory: “He was throwing stuff, and that’s mostly the take we used. It’s a combination of different takes, but that one was absolutely key. I just thought it was wonderful, but he hadn’t shot his side yet, and I worried he was going to lose his voice. But we came back the next day to do his side.”

“This is a case in point,” says Murphy, “where we were doing that big push. I remember going, ‘Do you think we got it, Chris?’ And you were like, ‘Eh. Let’s go again.’ I love that. You could say, ‘We can all go home now,’ but instead, you said, ‘Let’s just go again.’ Sometimes it doesn’t work, but that time it did.”

When the atomic bomb test succeeds, Oppenheimer is carried on the shoulders of others like a football coach who’s just won the Super Bowl. There’s even a scene in which Harry Truman (Gary Oldman), the president who dropped Oppenheimer’s bombs on Japan, is shown to be disgusted by the physicist’s remorse. But his role in the destruction and massive loss of life in Hiroshima and Nagasaki must have left Nolan with a real balancing act.

“As you put a script together,” he says, “you try and focus in on things like, what’s the key idea that has to work here? What are the key shifts that you need the audience to be struck by? And in the case of Oppenheimer, it was very clear to me that the whole purpose of the screenplay is to go from the absolute highest high of triumph, with Trinity, to the sheer lowest low of the realization of Hiroshima, in as short a time as possible.

“That was always going to be just a crazy shift,” he continues. “We talked about this a lot, in the moment where, earlier in the film, the atom is split. And then when Luis Alvarez [Alex Wolff] reproduces the experiment, in the script Oppenheimer immediately, as he did in real life, jumped to the idea that, you could make a bomb from this. The way in which Cillian performed that, it was very precise because it couldn’t be portentous. Obviously, he’s playing an intelligent man and he’s talking about bombs, but we couldn’t signal to the audience the negativity of where that was going to go, in terms of his frankly existential dilemma, the burden he’s going to carry later. You don’t want to foreshadow that in the performance. It was very important that the performance not foreshadow that, that it’d just be part of his journey that he’s interested in. To him, it’s actually exciting.”

In Nolan’s mind, the job is to paint a picture to help the audience form its own opinion about nukes, rather than betray his own morals and have it amount to feeding the audience cinematic spinach. “For me,” he says, “cinema can never be didactic, because as soon as it tells you what to think, you reject the art, you reject the storytelling. You see that a lot, particularly this time of year. It’s like people want movies to be able to send messages. But the truth is, I’m with whichever mogul who said, ‘Call Western Union if you want to send a message.’ In taking on Oppenheimer’s story, I don’t think there’s anyone who thinks that nuclear weapons are a good thing, so there’s not much point in telling the audience that.”

He pauses. “I’m sorry I’m going on a bit about this, but it’s a really interesting question. I had to explain this to everybody very early on: I’m not interested in making a story about how naive scientists accidentally created something that’s terrible for the world and then felt bad about it. Oppenheimer was one of the smartest people who ever lived. He knew exactly where this was going. The point is, they had to do it. They were put in a position where they believed that if the Nazis got the bomb, it would be the worst thing imaginable for the world. And so, they had to do what they had to do. But they did it knowing that the consequences would be potentially awful.

“That’s what makes the story so compelling from a human point of view. It’s not that they didn’t realize where this was going. It was that they felt they had no choice.”

Best of Deadline

Berlin Film Festival 2024 Red Carpet: 'Seven Veils' Premiere On Day 7

TV Cancellations Photo Gallery: Series Ending In 2024 & Beyond

Hollywood & Media Deaths In 2024: Photo Gallery & Obituaries

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.