‘One More Time With Feeling,’ Companion to New Nick Cave Album, Explores Pain and Loss: Venice Review

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

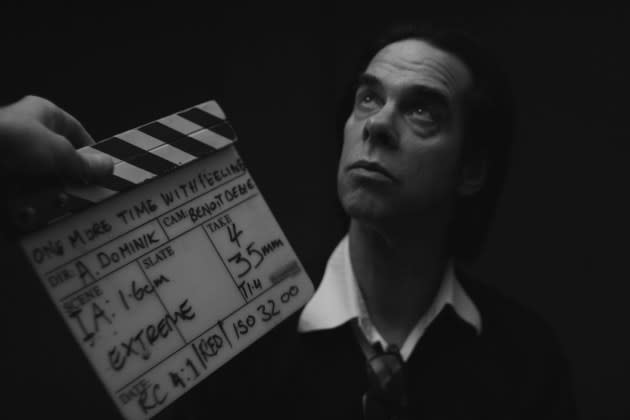

Nick Cave and Warren Ellis composed the score for Australian director Andrew Dominik’s first American feature in 2007, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the somber strains of their music enhancing the many moments of quiet contemplation in that revisionist Western. In what feels distinctly like a gesture of friendship, respect and sincerest sympathy, the director now gives back in One More Time With Feeling, a unique film chronicle of the recording of Skeleton Tree, the new album by Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds being released Sept. 9, the day after this film will be shown on some 650 screens worldwide for one night only.

What’s most singular about the project — beautifully shot in black-and-white 3D, which often gives the images a beguiling disembodied quality — is that in addition to providing access to the creative process and deepening the album experience, it serves as a profoundly affecting reflection on the pain of parents who have lost a child.

More from Billboard

Jann Wenner Removed From Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Foundation Board of Directors

NYC Mayor Eric Adams Gives Diddy a Key to the City During Ceremony in Times Square

Nick Cave Shares Trailer for 2016 Album & Film

Much of the work that has defined Cave’s career of more than 40 years in music — first with Boys Next Door, which became the Birthday Party, then later with the Bad Seeds and also as a prolific solo artist — might be described as the vivid narratives of a shamanistic balladeer. He admits he’s always been punctilious about the nuances of language in his songs. The material written for the new album, on the other hand, with many of its lyrics semi-improvised, comes from having rejected the notion that life follows predictable logic on a path to tidy resolution. The songs here are freeform elegies of a poet-preacher tapping into the unconscious.

The album’s opening track, “Jesus Alone,” begins: “You fell from the sky, crash-landed in a field near the River Adur.” That’s probably as close as the lyrics come to addressing directly the tragedy that struck the Cave family in July last year, when their 15-year-old son Arthur accidentally fell from a 60-foot cliff above Ovingdean Gap near their home in Brighton, England, and died of head injuries. But even at their most abstract, the ruminative songs are seeped in the dark wine of grief, loss and trauma too jagged and raw to be articulated. “With my voice, I am calling you,” intones Cave in the same song’s anguished refrain.

Dominik’s film could not be more different from 20,000 Days on Earth, the playfully enigmatic 2014 docufiction essay on Cave directed by Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard. But constant evolution and rebirth are an essential element of Cave’s music, so it seems right that any film focusing on such a restless creative force should be unlike whatever came before.

The pathos of One More Time With Feeling creeps up on you, in part because of the refusal of Cave to try to distil his feelings down into helpful platitudes. His very reserved wife Susie is even less willing to try. The intensely private nature of their grief notwithstanding, Nick Cave reached out to Dominik to document the making of the album because he felt he lacked objectivity about the material he had written during such a difficult period. And also out of an intuition that the people who cared about his music needed to be let in on the state of mind from whence it came.

Knowing the long history Cave shares with Ellis, his chief composing collaborator and longtime Bad Seeds bandmate, it’s quite moving to watch Ellis keeping a careful eye on Cave’s comfort levels, or humoring him in his moments of self-mocking vanity as they prepare to lay down a track. (“Is my hair all right?” “Never looked better.”) And when Ellis is not playing keys or violin but conducting, his unruly mane and beard and his conjuring fingers make him look like a wonderful mad wizard. The other Bad Seeds members tend to remain in the background, but watching drummer Thomas Wydler let loose in a trance-like number, he appears almost to be levitating over his kit.

The hypnotic qualities of the songs also find odd echoes in the physical side of the filmmaking process, notably when the crew circles with the massive, specially built 3D camera on a track around Cave at the piano. Even the technical glitches with the clunky equipment are acknowledged in amusing ways, as part of the film’s anxious, sometimes fumbling way of exploring the unimaginable. Many of the images captured by cinematographers Alwin H. Kuchler and Benoit Debie also are extraordinarily expressive, from Susie walking alone on the rocky beach, with Brighton Pier like a ghostly mansion in the distance, to seagulls swooping over the city’s near-empty streets.

Color is used only in two instances: one in snapshots taken by the Caves’ youngest son Earl during a warmly observed family studio visit; and another in the song “Distant Sky,” as Danish soprano Else Torp comes in on the vocal and the camera pulls back beyond the building to view first the city from above and then the coastline, the entire country, and finally, the planet from space. As a visual, it’s far more literal than anything else in the movie but effective all the same.

Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds Announce New Album, And It’s Hitting Movie Theaters First

While Dominik’s film is very much about the music, the personal insights are what make it so satisfying. The broad spectrum of coping mechanisms for surviving grief is evident in the touching contrast between Nick’s insistence that trauma is not an inspiration but an impediment to the creative process, while Susie finds work necessary in order to move forward. She’s seen constantly rearranging the furniture and attending to her projects as a designer, working on a collection that reinterprets the sister-wife prairie dress.

Both Nick and Susie Cave are reluctant to put the enormity of their loss into words, but it’s written on their faces as clearly as in the shattering Skeleton Tree songs. Aside from being heard asking the occasional tentative question, Dominik doesn’t push them. But there are wrenching moments such as Susie showing a painting she found in storage, done by Arthur when he was five, of a windmill near the scene of his death. And Nick’s sense of helplessness is apparent when he talks about not knowing how to respond to a local shopkeeper asking, “How are you?” Or crumbling in tears in the arms of concerned strangers. “When did you become an object of pity?” he asks himself. For an artist who has always inhabited a persona, the intimate exposure here is quite startling.

Dominik closes on a note of eloquent simplicity, with a sequence of face-forward shots of everyone involved in the production of the album and film, ending with the Cave family before cutting to footage of the cliff where Arthur fell. That image then continues to resonate over the end credits with a pre-existing recording of the song “Deep Water,” its music written by Cave and his sons with yearning lyrics by Marianne Faithful, sung by the two now-divided boys.

Venue: Venice Film Festival (Out of Competition)

Production companies: Iconoclast, Pulse Films, Bad Seeds

Cast: Nick Cave, Warren Ellis, Martyn Casey, Thomas Wydler, Jim Sclavunos, George Vjestica, Else Torp, Susie Cave, Earl Cave

Director: Andrew Dominik

Producers: Dulcie Kellett, James Wilson

Executive producers: Charles-Marie Anthonioz, Thomas Benski, Mourad Belkeddar, Marisa Clifford, Nicholas Lhermitte, Julia Nottingham, Anna Smith Tenser, Lucas Ochoa, Brian Message

Directors of photography: Alwin H. Kuchler, Benoit Debie

Music: Nick Cave, Warren Ellis

Editor: Shane Reid

Sales: Picturehouse Entertainment

No rating, 112 minutes.

This article originally appeared in THR.com.

Best of Billboard