‘One Child Nation’ Review: China’s One-Child Policy Comes Into Devastating Focus — Sundance

China’s one-child policy lasted from 1979 to 2015, becoming such an organic part of the country’s history and culture that it has been taken for granted around the world. With “One Child Nation,” Nanfu Wang pulls back the veil to reveal its devastating history.

Working with co-director Jialing Zhang, the filmmaker explores years of persecution and widespread fear engendered by the government’s enforcement of the policy. Using a remarkable personal lens, the film examines the reverberations of propaganda on broken families across multiple generations. The cumulative effect creates the sense that its destructive effects continue to be felt well beyond China’s borders.

Related stories

Big Buys at Sundance Mean Indie TV is Real, and Gaining Ground

'David Crosby: Remember My Name' Review: The Legendary Rocker Gets Real and Raw -- Sundance

Wang first probed the country’s broken justice system with her debut “Hooligan Sparrow,” which focused on a child rape case — but she turned in a more intimate work with her second feature, “I Am Another You,” in which she followed a young homeless man in America. With “One Child Nation,” she consolidates those modes by fusing her massive subject matter with her own point of view through a candid voiceover. Now the mother of a newborn, Wang contemplates the future for her U.S.-born infant in the context of her own childhood.

Growing up in a rural city, she wound up with a brother, due to an exception in the policy that allowed for two children in families outside of urban areas so long as the offspring were separated by five years. But the country’s trenchant enforcement of one-child households as the ideal way of life meant that her parents still lived under the pressure of the policy’s dark ramifications. As she learns from contemporary interviews with her family, officials at her village attempted to sterilize her mother after she gave birth to her first child. She avoided that fate, but other families weren’t so lucky, and Wang uncovers horrific accounts of women forced into crude surgeries that destroyed their lives.

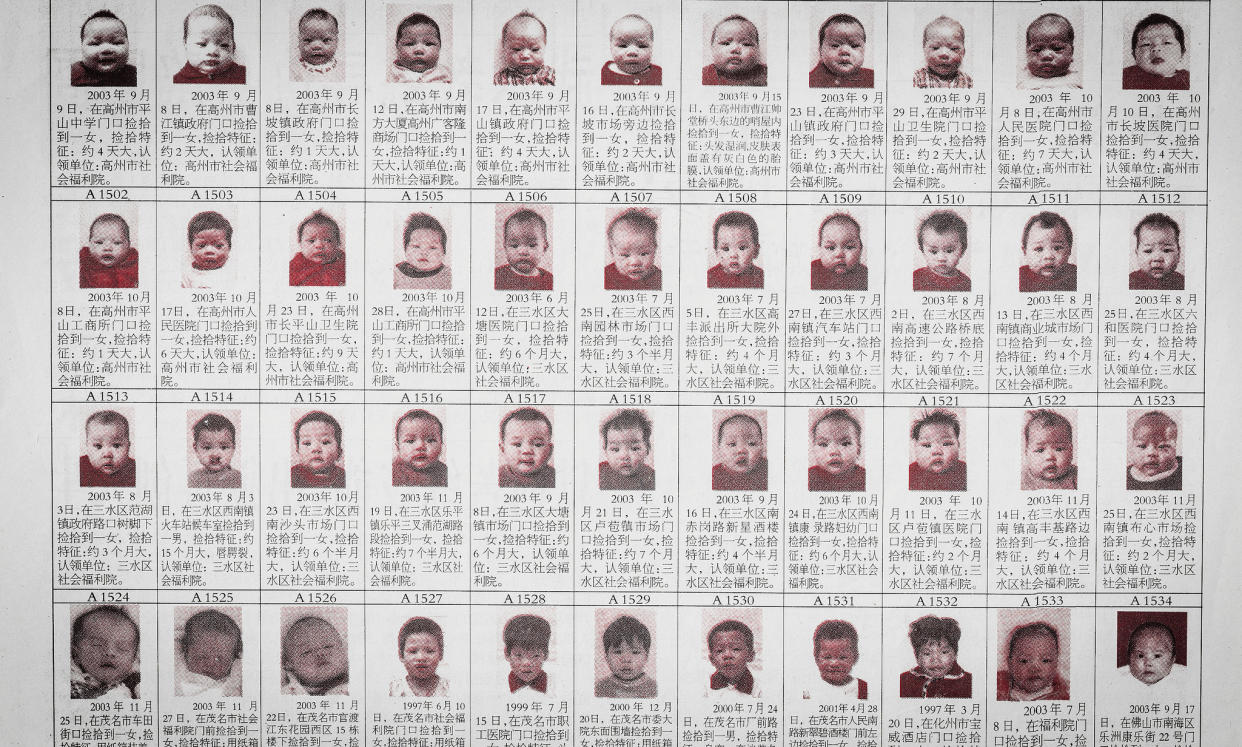

In even more harrowing cases, children were aborted, confiscated, abandoned — and, in some cases, sold to orphanages around the world. Wang merges personal accounts of these efforts by many people from her inner circle, including grief-stricken village elders, while unearthing harrowing photographic evidence of the surgeries in question.

That would be enough for a shocking documentary all on its own, but “One Child Nation” goes beyond these traumas to reveal their impact on lost children sent to other countries. One of the movie’s most intriguing passages revolves around the efforts of Brian and Long Lan Stuy, whose ongoing attempts to reunite adopted Chinese children with their birth parents involves a complex technological effort and many upsetting revelations about families torn apart.

As Wang veers from rumination about her own family to the broader context of the law in question, “One Child Nation” is a lot to take in, and sometimes strains from the sheer magnitude of the historical events. Fortunately, the directors maintain a brisk pace, uniting the disparate elements through Wang’s ruminative voiceover and yielding an uncompromising expose in absorbing, essayistic terms.

Ultimately, the policy provides an entry point for exploring gender discrimination embedded in Wang’s traditionalist household. Through photos she shares along with other bountiful archival material, she illustrates how her grandfather never posed for photos with her, considering only the men in the family to be sources of pride; when she attempts to connect with the elderly man now, she’s met with disinterest, as he explains that her marriage meant that she belongs to somebody else’s family now. In confrontations like these, Wang rarely appears on camera, instead standing behind the lens as the movie positions viewers within her conflicted perspective.

This troubling revelation points to the society’s broader sexist inclinations, which led to many of the upsetting cases of abandoned infant daughters, including several instances in Wang’s own extended family. As she coaxes several of her relatives to relive the past, she avoids an accusatory tone; living under the grip of propaganda and fear, they were driven to terrible extremes. But Wang herself refuses to accept the burden that tortures so many people close to her. “When every major life decision is made for you, it’s hard to feel responsible for the consequences,” she says.

As a brilliant combination of cultural reporting and interpersonal reckoning, “One Child Nation” manages to encapsulate decades of underreported events within a palatable narrative accessible to even to viewers with no prior understanding of the policy’s history. Lacing the edit with images of posters and music designed to reinforce the country’s repressive standards for family life, Wang reveals the intricate system that caused her and so many others to accept these restrictions throughout their youth and into early adulthood.

The movie’s melancholic score matches Wang’s meditative approach: She manages to unearth the painful ramifications of her upbringing without marginalizing other more harrowing accounts, including the details of forced abortions and infanticide. In a sense, she was one of the lucky ones, and while the movie doesn’t exactly strike an optimistic note, it does imply some degree of spiritual catharsis as Wang comes to terms with her past and contemplates a much better future for the new addition to her family.

But she’s wise to acknowledge that China’s problems hardly ended in 2015. The country’s insistence on controlling nearly every aspect of its population continues to haunt its citizenry, with the shift from one-child to two-child family policy yielding a whole new era of propaganda. In the somber finale, “One Child Nation” leaves the impression that while one upsetting chapter in China’s history has ended, the next one has only just begun.

Grade: A-

“One Child Nation” premiered in the U.S. Documentary Competition at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. It is currently seeking distribution.

Launch Gallery: Sundance 2019 Lineup Gallery: New Films From Festival Favorites and Many More