Off to work: Ringling photo exhibit ‘Working Conditions’ tracks history of labor

Western Civilization has always had a schizoid attitude about work. After various revolutions, we rejected the notion that common people were born to work and noble aristocrats were born to rule. No! Non! All work is noble! And civilization is always changing!

Starting in the late 19th century, the West (America, especially) celebrated a future of towering skyscrapers, shiny machines, and endless invention. Officially, workers were part of that march of progress. Unofficially, the elitist sneer survived – even in the United States. If you work with your hands, you’re a loser. That was a prevalent upper-class attitude. (Until recently, nobody said it out loud.)

“Working Conditions” at The Ringling, curated by Christopher Jones, Stanton B. and Nancy W. Kaplan Curator of Photography and Media Art, smartly captures this double vision. It’s a collection of 50 photographs drawn from the museum’s vast collection. The photographers keep the working class in their lens – but their focus can be drastically different. The main difference reflects the West’s ambivalence towards labor.

Some photographers celebrate the hard-working people who did the heavy lifting of industrial evolution. (Their workers tend to smile.) Others aim their cameras at shocking examples of capitalist exploitation. (Who don’t smile.)

Working life has a light side and a dark side. These photos show you both sides.

Looking at the bright side

Margaret Bourke-White was always looking up, sometimes literally. (I first saw her iconic image of a steel gargoyle on the new Chrysler Building at The Ringling years ago.) She has two striking photos here. “Industrial Rayon Corporation” (1939) is a cool, modernist composition of three women in a rayon factory. Spools of rayon in metal cases are lined up like tin soldiers on an assembly line. The women stand on either side, working away at various spools. They don’t seem like faceless cogs in a giant machine. They’re more like musicians playing in a gargantuan mechanical orchestra. I have no clue what these women are actually doing. But they’re good at it. And they know it.

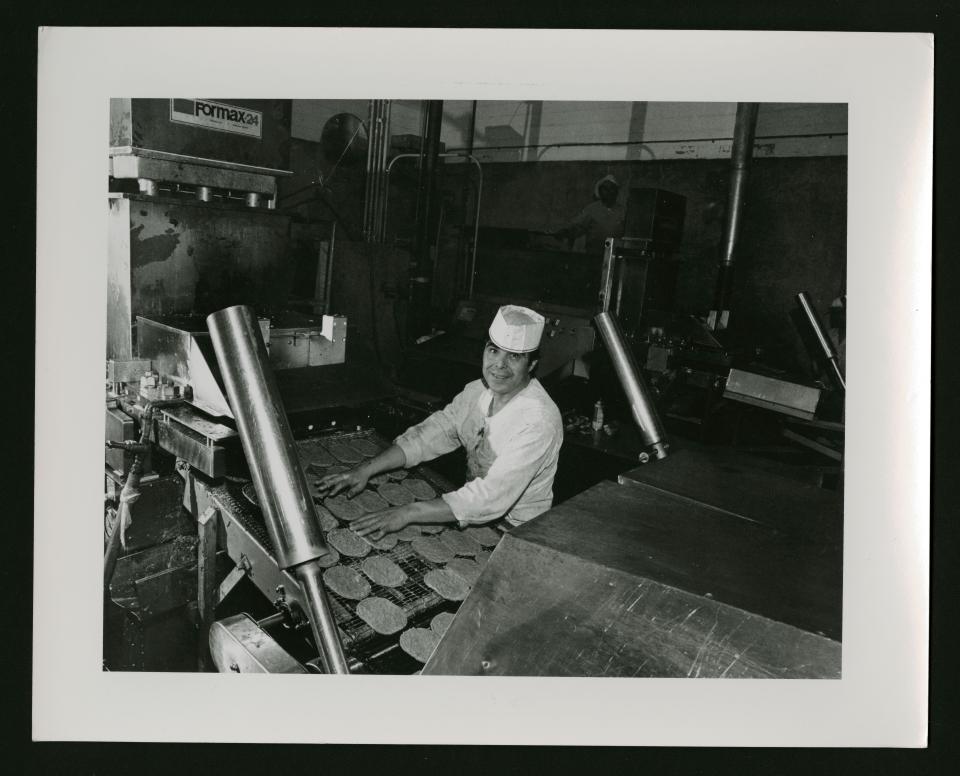

Bill Owens’ “Industrial burger maker” (1977) is another portrait of confident competence. It’s part of his photography series exploring the ways people felt about their jobs and themselves. Evidently, this “burger maker” felt pretty good about both. The man stands at a conveyor belt, feeding rows of hamburger patties into an industrial oven. Not the most glamorous task, but he’s got an ear-to-ear grin on his face. It’s a smile of pride with a hint of showmanship. You’d think he was leading a Broadway chorus line onstage. Suffering proletariat? Not this guy. But other workers weren’t so lucky.

A look into the dark side

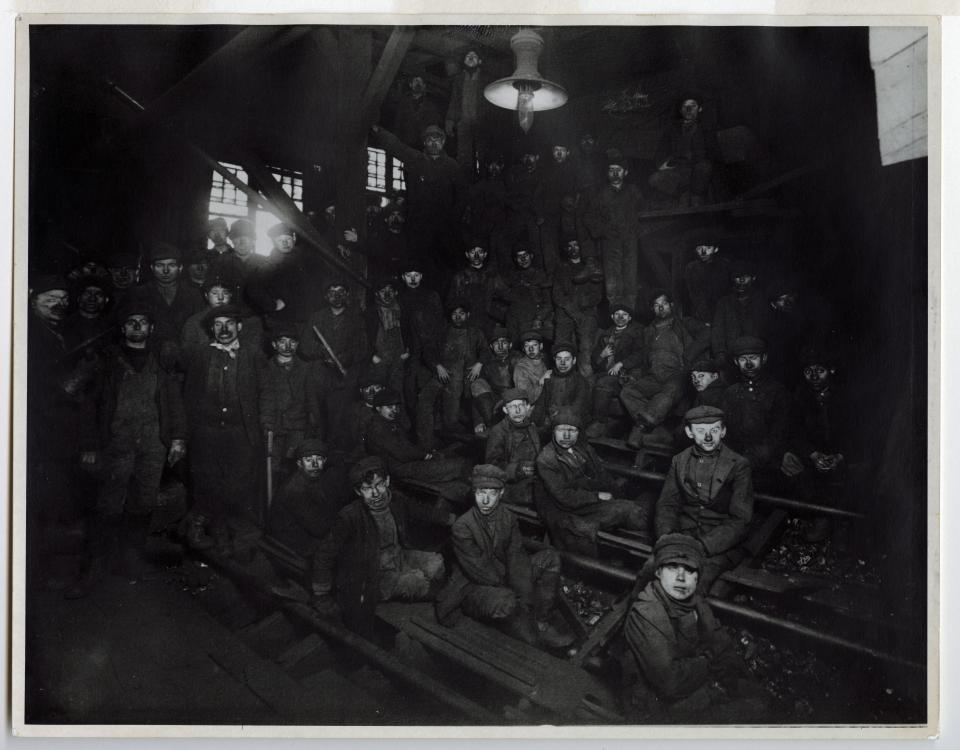

You want suffering? Look no further than Lewis W. Hine’s “Breaker Boys in a Coal Chute” (1911). This hellscape is downright Dickensian. A dimly lit, dirty room. It’s hard to make a count, but a few dozen boys are standing or sitting on rows of benches. They’re emaciated, filthy, and barely look human. How old? Fifth grade, sixth grade is my best guess. Instead of going to school, they are shoveling coal in darkness for 12 hours a day. Makes you angry, right? That was the idea.

Child labor was out-of-sight, out-of-mind in 1911. Hines wanted to make people see, make them angry, and make this practice illegal in the United States. His photos helped make that happen.

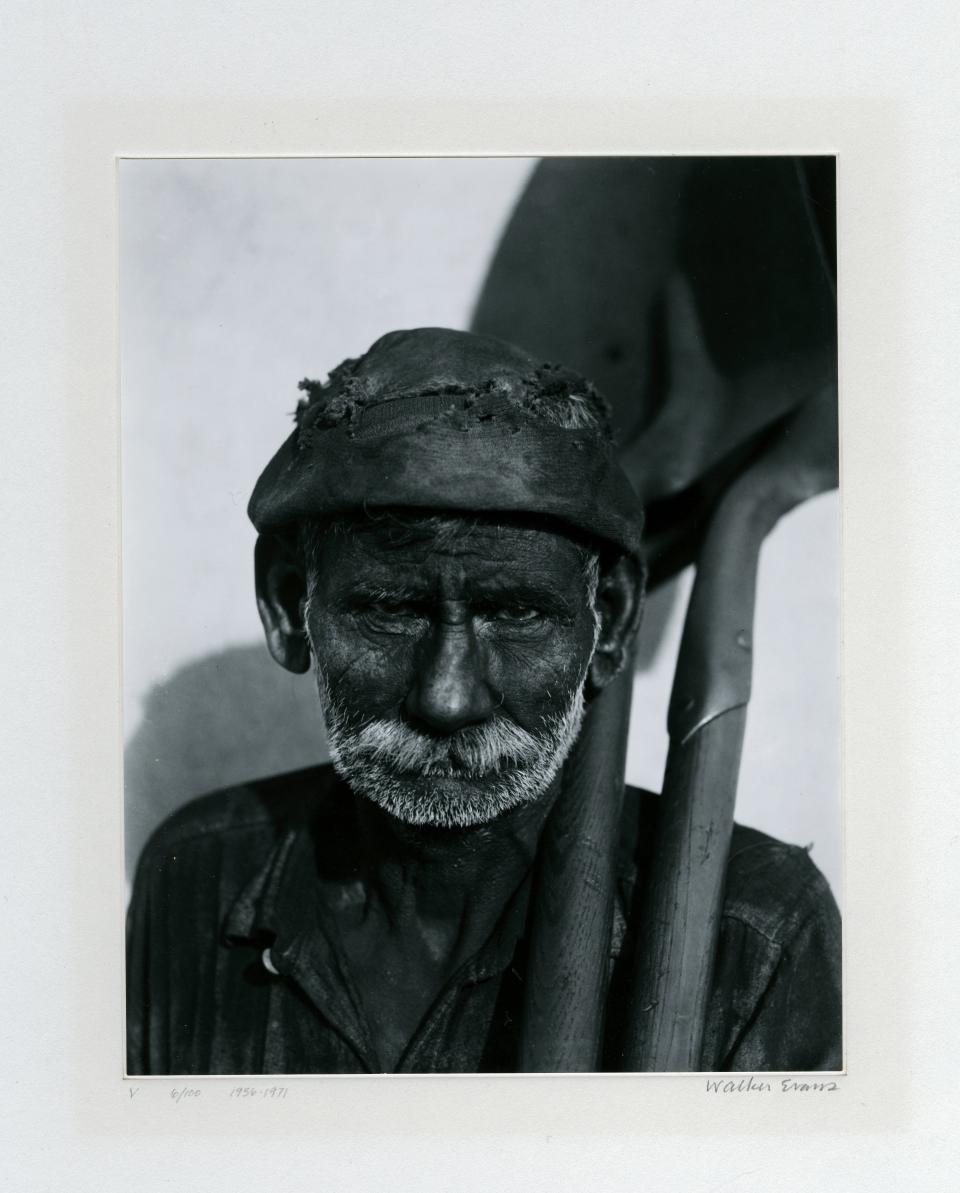

Walker Evans’ “Coal Dock Worker” (1933) resembles a hobbit. He’s tough, short, and no longer young. White mustache; white beard; black coal dust totally hiding his face. Except for his fiery eyes. He looks back at Evans’ camera with a defiant stare. His work is dirty and hard. His bosses are using him and using him up. He knows. But pride still burns in his eyes.

But the subject of Arthur Rothstein’s “Steelworker” (1937) is broken. The fire’s gone out of his eyes. He’s got that thousand-yard stare.

That’s the dark side of working life. The photos in this show reveal that, too.

Shiny, happy images of progress. Dirty, sad images of exploitation. You’ll see both sides here. Keep looking, and you’ll see many sides.

Politically engaged photographers display nuance

Hines went to war against the exploitation of workers. But he also applauded worker achievements. Hines’ “Raising the Mast, Empire State Building” (1932) honors the man who put the flagpole on top of the world’s tallest building at the end of construction. You know it took guts to do that. Then you realize Hines was somehow perched above this worker, aiming his camera straight down. That took even more guts.

Other nuanced portraits include Dmitri Baltermants’ Cuban fisherman with a strong resemblance to Ernest Hemingway; Danny Lyon’s chain gang boss straight out of “Cool hand Luke”; and Endia Beal’s proud Black professional woman’s defiance of the officially approved corporate stereotype. This photographic exploration of working life isn’t as simple as black-and-white – and it’s not all political. Though much of it is.

Many of the show’s photographers fought (and fight) to change perceptions. They all express their own perceptions. That goes beyond “I paint what I see.” The camera doesn’t lie, or it didn’t in the decades before digital trickery. With darkrooms, negatives and film, they show you exactly what they’ve seen. Photography is a visual art form. But it’s also a form of journalism.

An un-manipulated photograph is an objective document. A record of a specific moment. A freeze-frame of space-time.

This is what happened, in this place, and this time.

Assuming no fakery, after a photo leaves the darkroom, that information’s baked in.

What was working life like in the 20th and early 21st centuries?

Good question.

Check out this show for 50 good answers.

‘Working Conditions: Exploring Labor through The Ringling’s Photography Collection‘

Runs through March 3 in The Ringling’s Searing Wing, 5401 Bay Shore Rd., Sarasota; 359-5700; ringling.org

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Ringling photo exhibit ‘Working Conditions’ explores history of labor