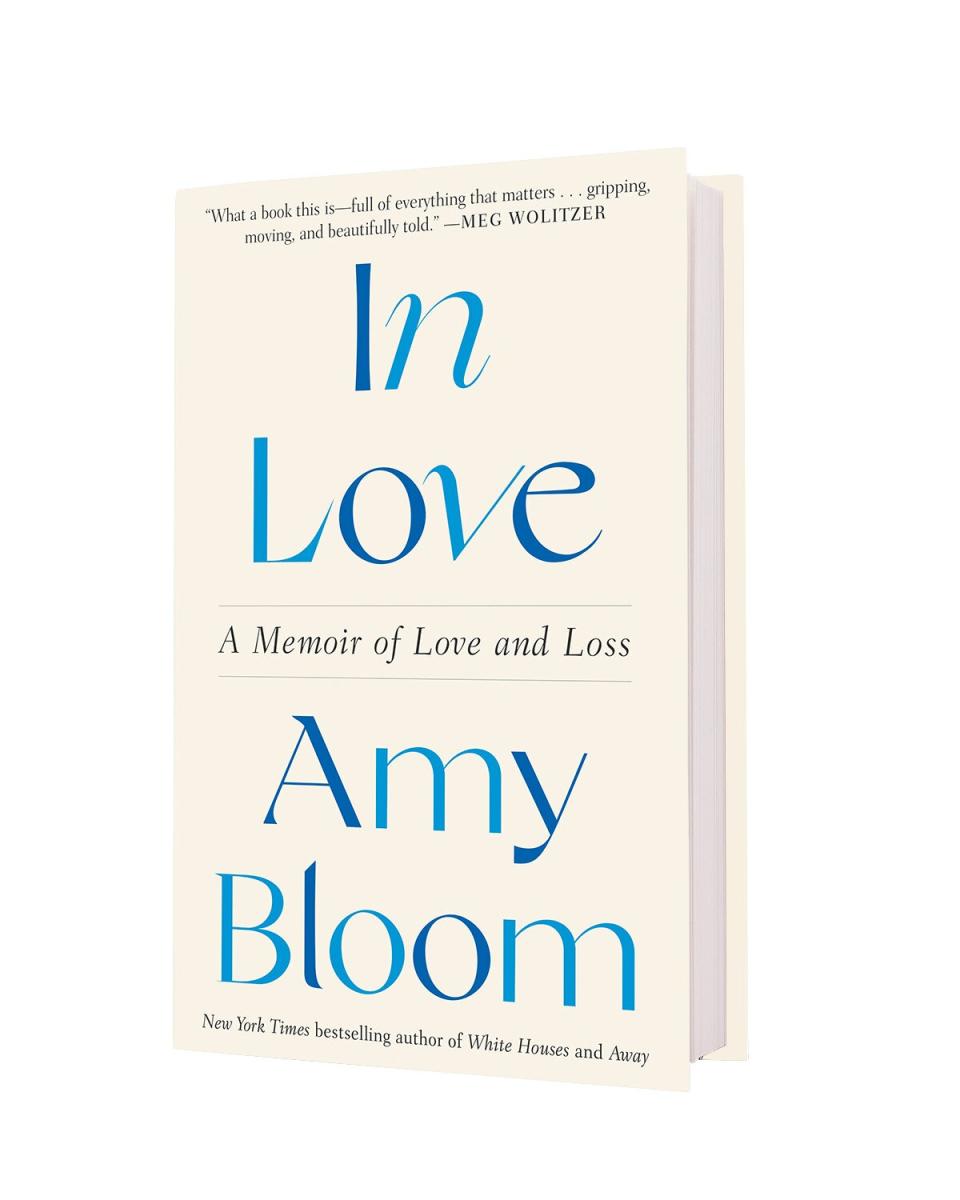

Novelist Amy Bloom Shares 'Excruciating' Journey After Her Ailing Husband Chose to Die By Assisted Suicide

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

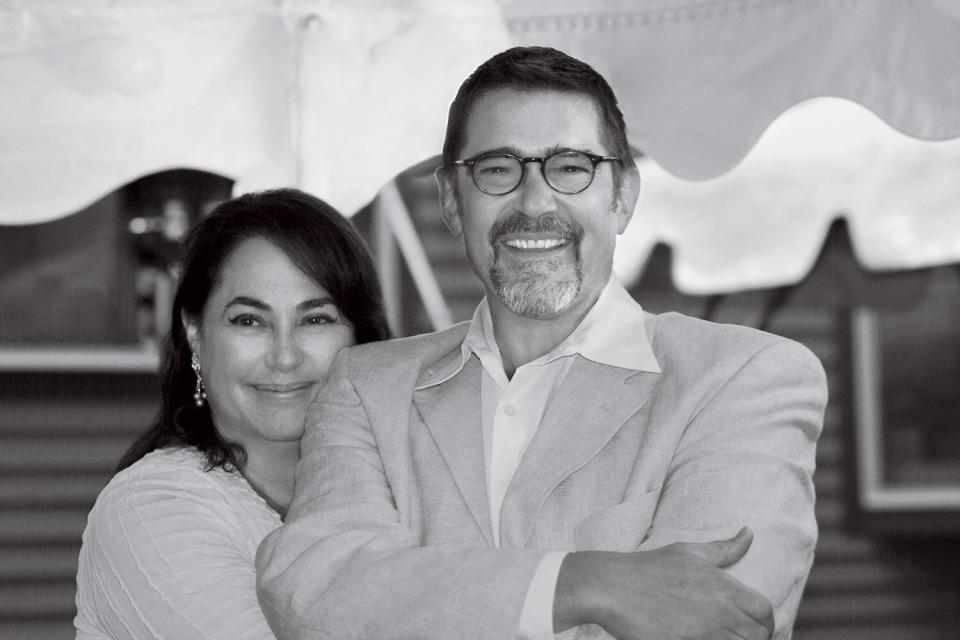

Elena Seibert Amy Bloom and her husband Brian Ameche, July 2017. Credit: Elena Seibert

When Amy Bloom fell for Brian Ameche in her mid-50s—"very much a midlife romance," she says—it was the architect's decisive zest for life that attracted her.

"What drew me to Brian was his warmth, and his energy, and a certain kind of fearlessness and full- steam-ahead for things. I did like and admire that," Bloom, 68, tells PEOPLE in an interview for this week's new issue.

"He was game, whatever it was. If you said, 'How about going to the mermaid parade in Coney Island?' He'd be like, 'Absolutely! Let's go!' "

After little red flags in his behavior had piled up for years— repeating himself, talking almost entirely about the past (often, his Yale football days), losing his balance— he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in the summer of 2019 at age 67. As for what came next, it did not surprise Bloom that he was as fearless as he was decisive.

"He knew what he wanted. He wanted to control his death and he wanted my support," says Bloom, who, at Ameche's insistence, tells their story in her new memoir In Love, out March 8. "He'd made up his mind after 48 hours and never wavered."

From watching a close friend's descent into Alzheimer's—a disease 6 million Americans are now living with—"Brian knew what to expect," Bloom says, her voice choked with tears. "I talked to him about living with the illness until the end—that, of course, I would love and take care of him. He was very kind and very clear. He just said, 'That's not for me.' "

But what Ameche decided was right for him—a painless and legal suicide before Alzheimer's stole everything he felt made his life worth living—would prove almost insurmountably difficult given America's limited right-to-die laws.

Just 10 states, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Vermont, Washington as well the District of Columbia allow doctor-assisted suicide for mentally healthy patients with no more than six months to live.

"He said to me, You go research it. You're so good at it," she writes.

And so Bloom took a leave from teaching creative writing at Wesleyan University and dedicated herself to the surreal task of ending her husband's life. She shopped with him for Snoopy stationery so that he could write goodbye notes to the four granddaughters who call him Babu. She scoured the internet for painless, fail-safe methods of suicide and prioritized "just being together," she says.

Beth Kelly Photography Amy Bloom and Brian Ameche on their wedding. 2007. Beth Kelly Photography. Durham, CT, 2007

Bloom's research led her to one of the few physician-assisted options for an Alzheimer's patient unable to thread the eye of the needle of U.S. right-to-die laws: Switzerland and a nonprofit "accompanied-suicide" organization called Dignitas.

But as Ameche's symptoms accelerated (weeks after writing his Snoopy cards, he couldn't remember the names of the granddaughters he'd addressed them to), it was a race to clear the Swiss clinic's hurdles—medical records, multiple psychiatric interviews and about $10,000 in fees—before Ameche lost the cognitive function to consent to death.

For more of PEOPLE's interview with Amy Bloom, pick up the new issue of the magazine on newsstands Friday.

"Every day it was scary and sort of heart-racing," Bloom says.

When they finally got the green light in January 2020, the Connecticut couple packed disposable carry-on bags—to spare Bloom the heartbreak of bringing her husband's suitcase home without him—for their four-day stay in Zurich before Ameche's scheduled death on Jan. 30.

"I very much wanted to make those days stand still," Bloom recalls. "It was painful, and sad. There were moments of connection and moments of real distance because I could feel that he was really moving away."

They mapped out restaurants and tourist spots to hit, but mostly lingered over pastries in a tea shop near their hotel.

"It was agony and tedium. We were passing time before this monumental end of the world," Bloom says. "It was an end for each of us, but a different kind of end. Brian was ready. I was working on being ready."

Courtesy Amy Bloom

That end came in a Dignitas apartment in the Pfaffikon suburb where the couple sat on a couch as two clinic staff affirmed Ameche's decision.

"He falls asleep holding my hand," Bloom writes. "His breathing changes, and it's the last time I will hear him sleeping, breathing deeply and steadily, the way he has done lying beside me for almost 15 years."

His death—"I could feel him passing. It was peaceful," she says—was "100 percent how he wanted it." On the flight home, she wore his wedding band on her forefinger.

RELATED: Terminally Ill Woman Brittany Maynard Has Ended Her Own Life

Bloom now hopes that her husband's story will get people talking about the end of life.

"Brian told me, 'Please write about this.' He wanted people to know that they have far less choice in America about their end of life than they may think," she says. "Some of us can't bear to think about it at all, but Brian felt strongly that people should have conversations and do more planning."

And then there's the never-to-be-realized plan she still holds in her heart—hatched when she and Ameche would walk in the summer past the home of an elderly couple, in their mid-80s, who sat in lawn chairs at the mouth of their garage.

"They would hoist their glasses of lemonade at us," says Bloom. "And Brian and I would wave and think, 'Oh! That'll be us. Watching the world, having lemonade. Happy.' "