How ‘Notturno’ Found the Soul of the Middle East in the Eyes of a Horse

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A version of this story about “Notturno” first appeared in the International Feature Film issue of TheWrap’s awards magazine.

It may have come as a surprise to some when Italy’s Oscar selection committee chose Gianfranco Rosi’s documentary “Notturno” to represent the country in the Best International Feature Film Race over the Sophia Loren vehicle “The Life Ahead.” But there was precedent for it, because Rosi’s last film, “Fire at Sea,” was the Italian Oscar entry in 2016.

And like “Fire at Sea,” which was nominated in the Best Documentary Feature category, “Notturno” is crafted from long, gorgeously composed takes of daily life for people affected by the strife in the Middle East. While his last film took place on the Italian island of Lampedusa, a destination for refugees, the new film is set along the borders of Syria, Iraq, Kurdistan and Lebanon, where mothers mourn lost children, kids draw pictures of ISIS attacks, soldiers go through exercises and refugees try to survive.

After “Fire at Sea,” which was set on the single island of Lampedusa, why did you move to a film that takes place across a huge expanse of territory?

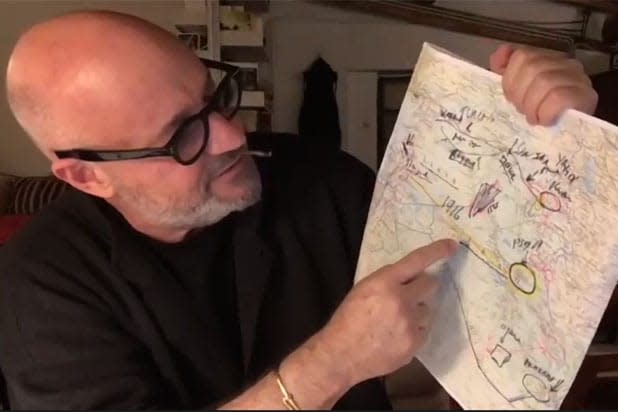

I wanted to deal with the invisible enemy. The war is just an echo, a long shockwave. There are thousands of films about war, but I wanted to film the echo of the war, the shockwave that it created on individual people. And to do that I needed to break up the idea of borders. The pain of a mother in Syria or Kurdistan is the same everywhere. It didn’t make any difference, the distance between Iraq, Syria, Lebanon or any other places I went through. And when we did the final edit, we decided to completely get rid of borders and have the story narrated by the individual encounters I had.

The film never identifies where we are — it just shows us these encounters.

It was very important for me to cancel the idea of separation, to create an idea of no more borders, no more division. That is the big challenge in the film, to transport us from one place to another and trust the narrative of the film. It was, how can I not give information without the audience being frustrated? It’s like a Giacometti statue — how thin can it go before it breaks?

Also Read: 'Notturno' Film Review: Middle East Doc Finds Poetry in 'Rubble and Darkness'

How do you gain the trust of people who have lost so much?

I spent six months without a camera, just encountering the stories. And when I (am ready to shoot), I might spend two or three weeks before the light was right, while the people I was with were carrying on their own lives. I just stayed with them and watched and created a trust. The best moments for me are when I don’t have the camera. I always say that making a film for me is about the 99% of things that I miss. But when I put the camera somewhere, I have so much intimacy with the situation I’m filming, and the part in front of the camera becomes a very cathartic moment.

I am able to observe and get intimate and somehow not to scare people because the camera creates separation. When you pick up the camera, you separate things. People say, “Oh, you feel invisible.” I’m not. I use a big camera. But before I pick up the camera, I’ve interacted with the situation and I’m established. And even then, no matter what, when you pick up the camera, things change. When you choose a frame, you’re telling a story and true objectivity never exists.

But I accept that the camera transforms things. It transforms the filmmaker and transforms the person that is in front of the camera. For me, it is always to try to find the language of cinema with the authority of documentary — to find the splendor of reality that is in front of you.

Gianfranco Rosi with a map of the territory he covered in “Notturno”

Do you know it when you find it, or do you discover the film in the editing room?

I spent three years in these places, and then I edited. And when I finished editing, I had the urge to go back again because I felt the film needed some pillars. I needed to go deeper in certain stories. So I did another journey.

It was a very difficult moment politically. There was a revolution going on in Iraq, in Lebanon, there was an invasion by Turkey of Syria. It was another heavy journey to do it, but I’m glad I did it because it created this pillar that I needed. I did that in October, November, December, January and February. I came back in February, and that’s when we locked down completely. I edited my film in this room and I really felt a sense of suspension and disconnection. There was a sense of silence and a sense of infinity that was very present in the field when I was shooting, and in the lockdown when I was editing. The film started resembling the mood outside.

That sense of silence is central in “Notturno.”

In each note, there is a space of silence. And it’s important to feel the silence. There is a scene with a horse, and I call the horse the silent oracle. This encounter with the horse was in a very important place, a road in Syria that runs through much of the conflict in the Middle East. Everything happens there. And one night I was filming this checkpoint, but I encountered his horse and he starts staring at me. I had the camera there to film something, so I just moved the camera, and this horse kept looking at me. And the horse didn’t move. And then after 45 minutes, the police arrived and said, “What are you doing here? Why are you filming a horse?”

(Laughs) But that horse was the only talking-head moment in the film, the only interview. And I think that horse says a lot. He gives more answers than if I asked a hundred questions to all the people that I encountered. I had a teacher who used to say, “If you ask one question, you get one answer. But that’s not interesting.” You need something more. If you don’t ask a question, you just follow the journey, and you may find something which is so profoundly intimate that it becomes a life

Read more from the International Film issue here.

Read original story How ‘Notturno’ Found the Soul of the Middle East in the Eyes of a Horse At TheWrap