Notes and tones: Memories of falling in love with jazz

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

[Note: The column’s namesake moniker is taken from a book of the same name: "Notes & Tones: Musician-To-Musician Interviews," written by Art Taylor, the great drummer. In the name of transparency, the columnist was involved in the presentation of the recent Blue Note performance referenced.]

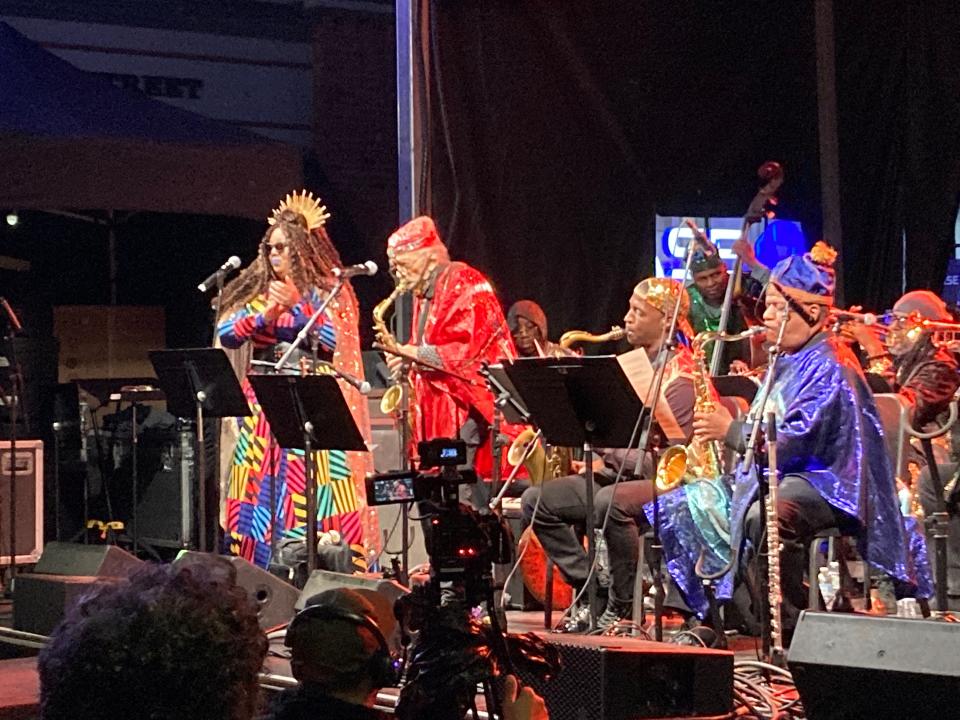

Seven weeks ago today, standing by the bar at The Blue Note — the one here in Columbia, not be confused with the jazz venue in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village — I heard the 13-piece Sun Ra Arkestra hit their first notes with a jolt.

Simultaneously and seemingly, everyone played freely and improvisationally as their respective individual spirits moved them. I’m quite sure, for many witnessing the colorfully-costumed ensemble for the first time, the “music” must have sounded like pure cacophony — or an orchestra tuning up before the conductor taps their baton on the podium, signaling a program’s formal start.

For me, however, I felt that sly, mischievous inner smile come to life, the one generally accompanied by a thought, a memory, a rekindling of remembrance from another time and/or place.

In that moment, I could pinpoint the date, July 9; the place, Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland; and approximate time — 8 p.m. local time — when I knew I officially fell in love with jazz and, eventually, many of its practitioners.

The experience I re-captured on this night did not invoke nostalgia. My reverie was not some inversely-proportional, back-to-the past variation of Don McLean’s overly saccharine “American Pie” ode to Buddy Holly.

Rather, my recollection was the opposite. It was my full-on understanding of that speck of time — granted, it was a four hour-long speck — in my soon-to-be universe where I knew, for lack of better phrasing, “Jazz is for me.”

Having, at that point, gone to hundreds, if not thousands, of concerts featuring the most inventive, fun and creative rock ‘n’ roll musicians; having studied what’s known in common vernacular as classical music; and having studied (European) music history and theory in college, what happened in Montreux on that summer night was no small epiphany.

My jazz courtship can be summarized as an ongoing relationship based on moving forward. That, by the way, is one of jazz’s numerous and most charming, if not endearing, characteristics. Jazz has always been and remains, along with other tenets, about moving forward.

This is not to say that a great many dedicated souls who wear the “I Heart Jazz” badge proudly and daily, enjoy everything that is new and fresh-sounding — “different” might be a better word — when it shows up in their ears. From time to time, I’d be lying if I didn’t count myself among them.

Historically, detractors and naysayers within the jazz community have railed against the music upon it taking a major turn. This is not dissimilar to the legend of, of all people, Pete Seeger — a most liberal, cause-fighting human being — yanking the plug from the socket in the middle of Bob Dylan’s “electric set” at the Newport Folk Festival.

Coming out of the big band era, post-World War II, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Max Roach, Bud Powell, and drummer-author Art Taylor were among those to launch bebop. Talk about a backlash from within. Yikes!

Even today, when some people see a lot of people on stage, in essence a “big band,” they’ll mutter, “That’s not big band music.” If you have 15-plus people on stage, sorry, that’s a big band — and they are playing music. How else would you characterize it?

When John Coltrane’s approach evolved from his 1950s modal-sounding music into longer, more dense compositions showcasing his now-revered “sheets of sound,” it was blasphemed, and not uncommon to hear people criticize the altered approach.

The Nov. 23, 1961, issue of Downbeat, courtesy of then-critic John Tynan, in part, ran this assessment: “At Hollywood’s Renaissance Club recently, I listened to a horrifying demonstration of what appears to be a growing anti-jazz trend exemplified by these foremost proponents [Coltrane and Dolphy] of what is termed avant-garde music. I heard a good rhythm section … go to waste behind the nihilistic exercises of the two horns ... Coltrane and Dolphy seem intent on deliberately destroying [swing] … They seem bent on pursuing an anarchistic course in their music that can but be termed anti-jazz.”

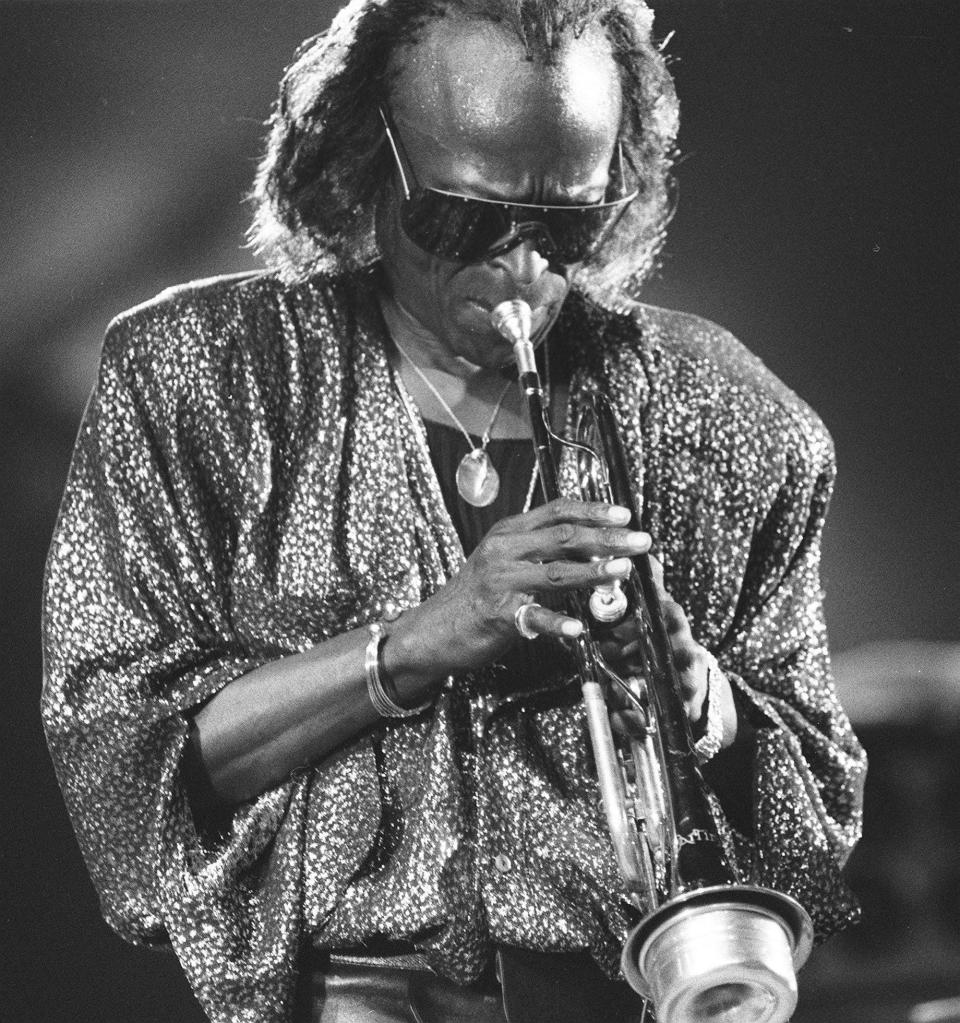

And then we have Miles Davis, who not only changed the face of jazz on more than one occasion, but also all American music. When he “went electric” a la Dylan, the backlash was horrific. In essence, Davis invented what we now refer to as “fusion” — initially, the term applied solely to the melding of jazz and rock ‘n’ roll.

Without Davis, there is no Weather Report, no Chick Corea Elektric Band, all the way down to — OK, I’ll make a judgment here — the dreaded smooth jazz and even Kenny G.

Though the icon’s “Kind of Blue” remains his most popular recording — and jazz’s most popular recording, which might say something about overall taste — listening to albums such as “Live at the Fillmore,” which I happened to attend as a high schooler, “In A Silent Way” and numerous other titles is nothing less than enthralling.

So, that recent night in The Blue Note, as I watched and listened to the Arkestra perform for two hours, all I could think about is how the group, more than 47 years ago, with Sun Ra — who died in 1993 — leading different personnel, set me on a forward-moving music trajectory forever.

Happy Holidays. See you next year. May the jazz be with all of us.

Jon W. Poses is executive director of the “We Always Swing” Jazz Series. Reach him at jazznbsbl@socket.net.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: Notes and tones: Memories of falling in love with jazz