Norton I Declared Himself Emperor of the United States, and His Subjects Loved It

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On July 16, 1860, 84 years after the American colonists signed the Declaration of Independence and officially stated their intention to form a union of their own, a decree was issued dissolving the United States of America entirely.

That Monday, San Franciscans woke up to a momentous proclamation: “Whereas, it is necessary for our Peace, Prosperity and Happiness, as also to the National Advancement of the people of the United States, that they should dissolve the Republican form of government and establish in its stead an Absolute Monarchy.”

The Civil War is Not Just For Americans

It was something of a formality as the man behind the edict, the self-proclaimed Emperor Norton I, had already declared himself “Emperor of the United States” a year earlier, thus establishing the American monarchy. But he had allowed the United States democracy to continue, even as its representatives ignored his orders to attend meetings to revise the country’s laws.

But in that year leading up to the outbreak of the Civil War, America’s benevolent ruler had had enough. There was too much animosity and strife—the bad behavior had gotten out of hand. It was his duty to take over.

If you were awake for even a single day of school during your entire education, you will know that this proclamation also went unheeded. Norton may not have made it into mainstream American curriculum, but in a city that produced a history book full of characters, the man who declared himself emperor is one of the most distinct and beloved. With the clarity of hindsight, we can also say our country might have fared a bit better if we had heeded our one and only monarch.

Emperor Norton I was born Joshua Abraham Norton around 1818 in London, though his family emigrated to South Africa when he was 2. Norton’s father was a businessman in the shipping industry, and Norton decided to follow in his footsteps.

But early adulthood was a rough time for young Norton. By the age of 23, his first shipping venture had gone bankrupt; within a few years of that failure, he lost both of his parents and all of his siblings. As his thirties neared, he decided it was time for a change. With the money left after settling his family’s affairs (some accounts have put his inheritance at $40,000, though there is no hard evidence for this number), Norton left South Africa and moved to Gold Rush-era San Francisco in 1849.

Norton quickly made a name for himself in the small but booming frontier town. He continued his work in shipping and sales, while also dipping a finger into the real estate market. Within three years, he had considerably increased his fortune enough to be considered a member of San Francisco’s high society.

“He was in with all the right people, attended all the right clubs and all the right restaurants,” John Lumea, founder of the Emperor Norton Trust, told KQED.

But all it takes is one bad business decision for one’s social standing to come tumbling down. And that’s what happened in 1852.

When Norton became emperor, he committed his reign to the betterment of society. While some of his decrees were outlandish, many of them also had a grain of truth to them, diagnosing what was wrong with American society and offering concrete suggestions for improvement.

But the deal that took the civilian Norton down was one that was not so civic-minded.

At the end of 1852, China was in the middle of a famine. To combat the scarcity of food its own citizens were experiencing, the government outlawed all rice exports. This move was felt around the world as the price of rice dramatically increased. According to Dana Schwartz, host of the Noble Blood podcast, the price of rice in San Francisco rose from four cents a pound to 36 cents a pound.

Around this time, Norton was approached about a new opportunity. There was a ship full of Peruvian rice in the harbor, the last ship of its kind expected for awhile, he was told. Norton bought 200,000 pounds of rice—the entire shipment—for around $25,000. He planned to be the sole dealer in the commodity for the foreseeable future.

One can only imagine what went through his mind when, soon after the deal was complete, several more ships sailed into the harbor, each weighed down with the coveted grains.

The ensuing fallout destroyed Norton’s finances and his place in San Francisco society. Several of his business partners sued him in a case that lasted for four years and made it all the way to California’s Supreme Court. In 1858, Norton filed for bankruptcy and disappeared.

Just over a year later, on September 17, 1859, “a well-dressed and serious-looking man” entered the offices of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin. With zero fanfare, he handed the editors a document and asked them to run it in the evening’s paper. They read it, and agreed.

“At the peremptory request of a large majority of the citizens of these United States, I, Joshua Norton, formerly of Algoa Bay, Cape of Good Hope, and now for the last nine years and ten months past of San Francisco, California, declare and proclaim myself Emperor of these United States,” the bulletin in the paper read.

The reign of Emperor Norton I had officially begun, if only in Norton’s mind.

Many have speculated as to what happened to Norton to bring about this turn of events, but what hasn’t been disputed is that Norton truly believed in his royalty and in the responsibilities that position entailed. (Throughout his reign, he would send several letters to Queen Victoria urging her to marry him so that their two countries could once again be aligned.)

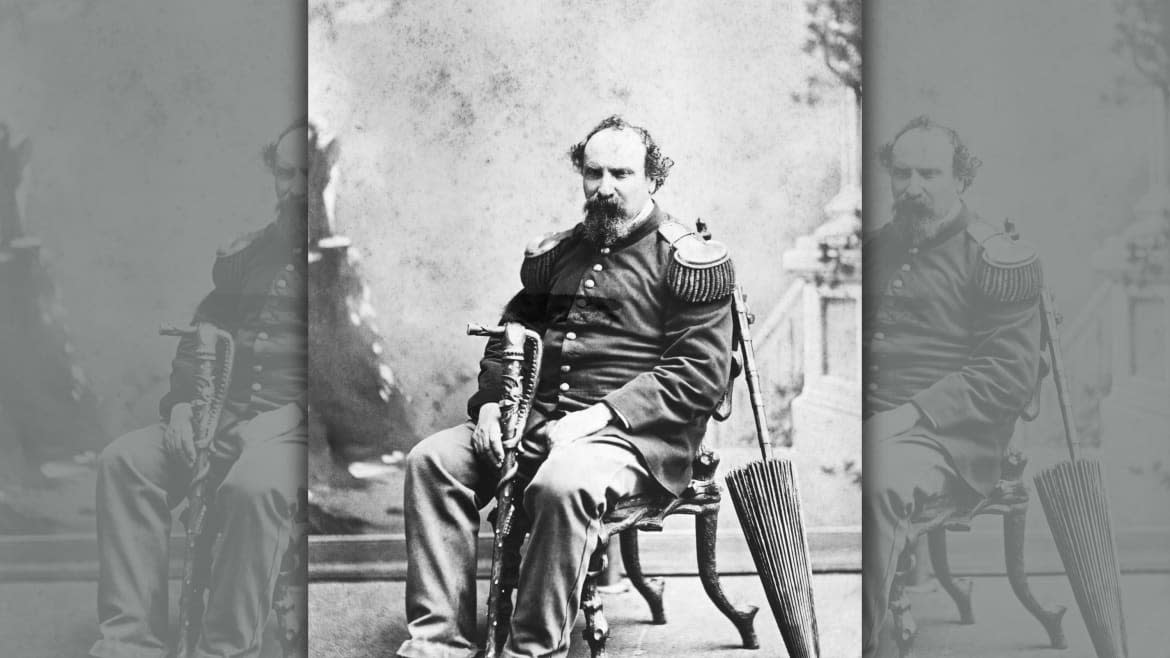

At first, the strange man was largely ignored, no doubt an easy attitude to take in a city that was full of Gold Rush eccentrics. But then he acquired a military uniform and began making rounds in the streets to check on his citizens, and people began to take notice.

His presence was not always received with the open arms that his memory is today. Particularly in the early days of his “rule,” he was sometimes ridiculed, particularly by newspapers who weren’t his chosen megaphone for his latest edicts.

But slowly the city began to embrace him, and he become shorthand for anyone trying to make a civic point. (In 1868, the San Francisco Examiner good-naturedly evoked the name of “Emperor Norton I” to protest a local government alcohol restriction that the paper did not agree with.)

It wasn’t hard to embrace his reign once he established his progressive agenda. His decrees may have been ignored by the democratic government of the U.S., but many of them probably shouldn’t have been.

In December of 1859, he ordered the removal of the governor of Virginia for executing the famous abolitionist John Brown. In 1869, he “dissolve[d] and abolish[ed]” the Republican and Democratic parties because he was “desirous of allaying the dissensions of party strife now existing within our realm.” (The penalty for any politician who ignored his decree: imprisonment for up to 10 years.) Later that year, he ordered Sacramento to clean up its streets and install street lights.

In 1863, he took on a new title “Protector of Mexico” after Napoleon invaded the country. (He gave it up nearly a decade later, declaring "It is impossible to protect such an unsettled nation.”)

Perhaps his most prophetic decree came on Sept. 21,1872, when he ordered San Francisco to begin a serious inquiry into erecting either a bridge or tunnel to connect the city with Oakland. Sixty-one years later, the Bay Bridge would be built to do just that.

When Emperor Norton I wasn’t trying to right the wrongs of the U.S. or make improvements to the cities of California, he could be seen among his subjects. He walked the streets in his military uniform (often gifted to him by tailors who would then advertise their honored position with a window sign: “by appointment to His Majesty”); he attended the theater in seats generally comped to him; and he often paid for his dinner and other very modest expenses with his own royal currency, issued by a local printer and accepted by many in town.

He lived a pauper’s life in private, but his public activities were avidly reported on. In a 1944 article in the California Historical Society Quarterly examining the historic 1860 visit to San Francisco by the first Japanese emissaries to the U.S., George Hinkle notes that the San Francisco Bulletin didn’t even mention the Japanese emissaries in attendance at the McGuire Opera House on the evening of March 28.

Instead, their report had eyes for only one honored audience member: “No one was desirous to intrude upon his Imperial Majesty, and so he had a row of front seats all to himself. He looked ‘every inch a king.’ His nose particularly—and this is the feature of which he feels most proud—is said to closely resemble that of George IV. Blood will tell.”

On Jan. 8, 1880, the reign of America’s only monarch came to an end after more than two decades when Emperor Norton died of what was probably a stroke. Local papers ran his obituaries while tens of thousands of people from all classes of San Francisco society turned out to his funeral. They made sure that he was buried as a king, and not laid to rest in a pauper’s grave.

“Now that we’ve moved past fiefdoms and protectorates, maybe the entire notion of royalty, of someone being born more worthy of power than someone else, is a little bit insane,” Schwartz says. “And there’s certainly nothing more American than a man who decided what he wanted to be, and then lived it.”

Today, his subjects can still make a pilgrimage to his gravesite in Woodlawn Cemetery, where his gravestone proclaims, “Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.