Norman Lear, Sitcom Genius and Citizen Activist, Dies at 101

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Norman Lear, the writer, producer and citizen activist who coalesced topical conflict and outrageous comedy in such wildly popular sitcoms as All in the Family, Maude, Good Times, Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman and The Jeffersons, has died. He was 101.

Lear died Tuesday at his home in Los Angeles surrounded by his family who, according to a statement on his official Instagram account, sang songs until the very end.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

“Norman lived a life in awe of the world around him. He marveled at his cup of coffee every morning, the shape of the tree outside his window, and the sounds of beautiful music,” read the post. “But it was people — those he just met and those he knew for decades — who kept his mind and heart forever young. As we celebrate his legacy and reflect on the next chapter of life without him, we would like to thank everyone for all the love and support.”

One of the seven original inductees into the TV Hall of Fame in 1984 (he entered with David Sarnoff, William S. Paley, Edward R. Murrow, Paddy Chayefsky, Lucille Ball and Milton Berle), the six-time Emmy winner, who teamed often with fellow writer-producer Bud Yorkin, also developed Sanford & Son and One Day at a Time, among many other comedies.

He and Yorkin came to prominence writing for Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin’s variety show in the 1950s, and at one time, Lear had nine shows on the air and finished one season with three of the top four highest-rated series.

Lear adapted Neil Simon’s Come Blow Your Horn for a 1963 film directed by Yorkin and cajoled Frank Sinatra into starring in it, received an Oscar screenplay nomination for Divorce American Style (1967) and co-wrote and produced William Friedkin’s The Night They Raided Minsky’s (1968), at the time the most expensive movie to be made in New York City.

Later, he provided the funding for such films as This Is Spinal Tap (1984), Stand by Me (1986), The Princess Bride (1987) and Fried Green Tomatoes (1991). The first three were directed by Rob Reiner, who taught Lear’s daughter Ellen how to play jacks when the kids were both 9 years old and went on, of course, to star as “Meathead” Michael Stivic on All in the Family.

“I loved Norman Lear with all my heart. He was my second father,” Reiner posted on X, formerly Twitter, on Wednesday.

President Joe Biden attended a shiva to mourn Lear, at his residence in California, according to the White House. The president also paid tribute to the Hollywood icon earlier in the week, calling him a “transformational force in American culture” whose shows “redefined television with courage, conscience, and humor, opening our nation’s eyes and often our hearts.”

In 1981, Lear, a famed Hollywood liberal, co-founded the nonprofit People for the American Way, whose vision “is a vibrantly diverse democratic society in which everyone is treated equally under the law, given the freedom and opportunity to pursue their dreams and encouraged to participate in our nation’s civic and political life.” Twenty years later, he purchased an original copy of the Declaration of Independence at auction for $8.1 million and took it on a tour around the country for a decade.

“Norman knew the power of culture to generate conversation, reach hearts and change minds — and he was a master at using that power for good,” People for the American Way board co-chair and longtime Lear confidante Lara Bergthold said in a statement.

A two-fingered typist, Lear also was known for the headwear he first donned so he wouldn’t pick at his bald head during bouts of writer’s block. “One day [his second wife] Frances came into my study and threw a little white boating hat on my head to keep me from picking. It worked, and that is how my nearly 50-year love affair with that white hat began,” he wrote in his 2014 memoir, Even This I Get to Experience.

Yorkin, in England directing Inspector Clouseau (1968), watched an episode of the BBC’s Till Death Us Do Part, a sitcom that centered on a bigoted father and his liberal son who bickered all the time, and brought it to Lear’s attention.

“Oh my God, my dad and me,” Lear wrote in his book.

“As a kid, when I wasn’t moving as fast as he thought I should, [Lear’s father] H.K. would call me ‘the laziest white kid he ever met.’ When I’d accuse him of putting down a whole race of people just to call his son lazy, he’d yell back at me, ‘That’s not what I’m doing, and you’re the dumbest white kid I ever met!’ ”

For the series that would become All in the Family, he and Yorkin secured the rights in September 1968 and had Mickey Rooney in mind for Archie Bunker, but the actor didn’t think the series would last. “You want to do a show with The Mick, listen to this: Vietnam vet. Private eye. Short. Blind. Large dog,” Rooney told Lear.

ABC passed twice on the series before CBS, then looking to wean itself of rural comedies like Green Acres and Petticoat Junction, signed on. And so, with Carroll O’Connor as the racist Archie, Jean Stapleton as his naive wife Edith, Sally Struthers as their daughter Gloria and Reiner as their Polish-American son-in-law, All in the Family, taped before an audience of about 250 in Hollywood, debuted at 9:30 p.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 12, 1971.

It began with this disclaimer:

“The program you are about to see is All in the Family. It seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show — in a mature fashion — just how absurd they are.”

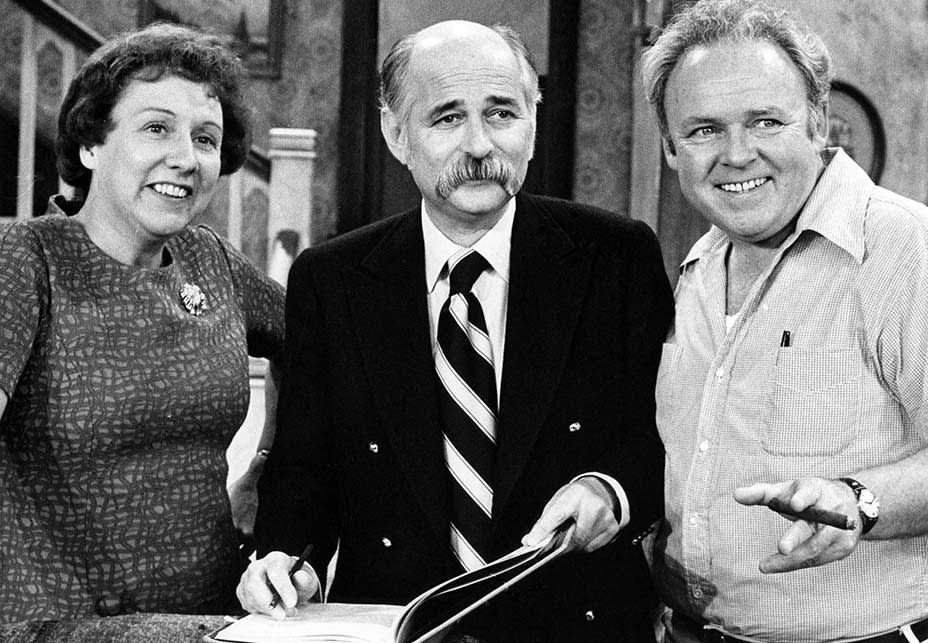

Norman Lear (center) with ‘All in the Family’ stars Jean Stapleton and Carroll O’Connor

All in the Family was No. 1 in the ratings for an unprecedented five years. At its peak, 60 percent of the viewing public, more than 50 million people, tuned in on Saturday nights.

“[All in the Family] endures because its creator was angry about injustice in the world: racism, sexism, homophobia, abuse of political power, economic disparity — the list goes on. In other words, angry about the right things, Seth McFarlane wrote in Vanity Fair in 2014.

More recently, the energetic Lear rebooted One Day at a Time for Netflix (and then Pop) with a Latino cast and saw episodes of All in the Family, The Jeffersons and Good Times revitalized for ABC specials that made him the oldest Emmy winner ever.

In February 2021, he received the Carol Burnett Award via Zoom at the Golden Globes. “I am convinced that laughter adds time to one’s life, and no one has made me laugh harder … than Carol Burnett,” he said. Eighteen months later, he reminisced with THR‘s Lacey Rose after turning 100.

Lear was born to Jewish parents on July 27, 1922, in New Haven, Connecticut. His father, Herman, known as H.K., was a scheming salesman who did jail time. His mother, Jeanette, was a housewife who often was told to “stifle” when H.K. wanted her to be quiet.

Lear wrote a speech, “The Constitution and Me,” that won him a scholarship to Emerson College in Boston, where he majored in drama. He enlisted in the Army Air Forces during World War II, flying 52 missions over Europe in a B-17 bomber, and said he was lucky to survive.

Following his discharge in 1946, he landed a job as a press agent for a Broadway publicity firm, getting $40 a week. In his first month, he fabricated an item that ran in Dorothy Kilgallen’s column in the New York Journal-American that said, “Kitty Carlisle gifted friend Moss Hart with a pocket flask measured to his hip while he napped.” Carlisle and Hart met for the first time because of the item and later married.

But after another (untrue) item about little people made it into another column, he “was summarily dismissed, and without severance,” he wrote in his book. He then went to work for his father, who was trying to convince someone to mass produce his nonelectric refrigerator.

Lear moved to Los Angeles to try his hand again at publicity. On his first night in town, in spring 1949, he stumbled onto the Circle Theatre in Hollywood, which was staging George Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara. In walked Charlie Chaplin to watch his son, Sidney, perform. (Also in the play that night were Strother Martin, William Schallert and Diana Douglas, Michael Douglas’ mother.)

He and his cousin’s husband, Ed Simmons, began writing comedy bits at night, and they sold nightclub comedian Danny Thomas a routine for $500. They pitched two sketches to Jack Haley, the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz who was launching a live NBC variety show, and landed a job in New York as Haley’s staff writers. (Lear and Simmons later hired brothers Neil and Danny Simon to help them out.)

Lewis, who was about to host the Colgate Comedy Hour with Martin, liked a Lear-Simmons bit he saw on the Haley show and swiped them for the Lewis-Martin variety hour in 1950. (He and Lewis did a routine before each airing to warm up the audience.) In 1954, Lear and Simmons moved to The Martha Raye Show.

When Raye’s show was canceled, Yorkin, who was a stage manager and later a director on the Colgate Comedy Hour, asked Lear and Simmons to write for a new variety show hosted by country singer Tennessee Ernie Ford. Lear agreed but Simmons said no, ending their partnership. In 1958, Lear wrote for and produced a variety show led by George Gobel.

A year later, Yorkin — a hot commodity after he produced and directed An Evening With Fred Astaire, the first musical hour to be shot in color — and Lear formed Tandem Productions, and they inked a three-year deal with Paramount to develop TV shows, specials and films.

Tandem packaged NBC’s The Andy Williams Show, and the company’s first feature was Come Blow Your Horn.

Lear co-wrote and produced the $3 million musical The Night They Raided Minsky’s, starring Jason Robards and Britt Ekland. He produced Start the Revolution Without Me (1970), toplined by Gene Wilder and Donald Sutherland, and co-wrote, directed and produced the comedy Cold Turkey (1971), which starred Divorce American Style star Dick Van Dyke in the story about an entire Iowa town trying to stop smoking.

United Artists offered Lear a three-picture deal to produce, write and direct, but Lear turned it down, going all in for television.

Lear and Yorkin brought Sanford and Son, based on another British series and starring bawdy Las Vegas stand-up Redd Foxx as a junkman, to NBC. The show, supervised by Yorkin, debuted in January 1972 and lasted six seasons.

CBS’ Maude starred Bea Arthur as Edith’s cousin Maude Findlay and polar opposite of Archie. In the spinoff’s first season, Arthur’s character, who was nearing 50, decided after much soul-searching to have an abortion. Two affiliates did not air the two-part episode, the first time any CBS station had rejected an installment of a continuing series.

“Of all the characters I’ve created and cast, the one who resembles me the most was Maude,” Lear wrote in his book.

Maude’s maid Florida (Esther Rolle) became the matriarch of CBS’ Good Times, set in the Cabrini-Green housing projects in Chicago. The idea for CBS’ The Jeffersons, a spinoff featuring the Bunkers’ neighbors who strike it rich and move to a Manhattan “deluxe apartment in the sky,” came to Lear after members of the Black Panthers visited him to complain about Good Times being “a white man’s version of a black family.” The Jeffersons lasted a whopping 11 seasons.

In 1974-75, All in the Family was No. 1 in the ratings, followed by Sanford and Son (No. 2), The Jeffersons (No. 4), Good Times (No. 7) and Maude (No. 9).

The delightful soap satire Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, starring Woody Allen’s ex-wife Louise Lasser, was sold in syndication to 128 stations outside the three-network system and aired for two seasons in late night, five nights a week. That show spawned Fernwood 2 Night, starring Martin Mull as a talk show host and twin brother of a character who had been impaled on a Christmas tree on Mary Hartman.

Lear made millions selling his share of Tandem/Embassy Communications to the Coca-Cola Co. (which earlier had bought Columbia Pictures) in 1985. He later formed Act III Communications, which owned theaters, independent TV stations and trade publications, and bought Concord Records, merging it with an Australian company to form the Village Roadshow Entertainment Group.

Lear was married three times: to Charlotte Rosen, whom he met in high school, from 1943-56; to Frances Loeb from 1956–85 (she claimed to be the inspiration for Maude and received $100 million-plus in her divorce settlement from Lear); and to former teacher Lyn Davis, whom he wed in 1987 and who survives him.

Lear had six children — Ellen, Kate, Maggie, Benjamin and twins Brianna and Madeline — with the youngest and oldest 48 years apart. Kate’s husband is Jon LaPook, medical correspondent for the CBS Evening News, and Maya Angelou was the godmother of his twin daughters. He is also survived by four grandchildren.

In his memoir, Lear wrote that he learned a lesson about comedy from the live audience that gathered for the taping of All in the Family each week.

“The audiences themselves taught me that you can get some wonderful laughs on the surface of anything with funny performers and good jokes, but if you want them laughing from the belly, you stand a better chance of achieving it if you get them caring first,” he wrote. “The humor in life doesn’t stop when we are in tears, any more than it stops being serious where we are laughing. So we were in the game to elicit both.”

Launch Gallery: Norman Lear's Life and Career in Pictures

Best of The Hollywood Reporter