Noah Hawley Has Been Offered the World, But ‘Fargo’ Keeps Calling

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For the past 15 years or so, Noah Hawley has called Austin, Texas, home. Sure, he’s spent long stretches elsewhere — Calgary for FX’s Fargo, Bangkok for his forthcoming series Alien — but home, where his wife and two children (ages 16 and 11) reside, is 1,400 miles from Hollywood. And, as Hawley sees it, it’s served him well. “I always say I want to tell stories for everybody, and it helps not to be in a coastal bubble if you want to do that,” he says in early November. “And sure, Austin is its own bubble, but I do like the remove.”

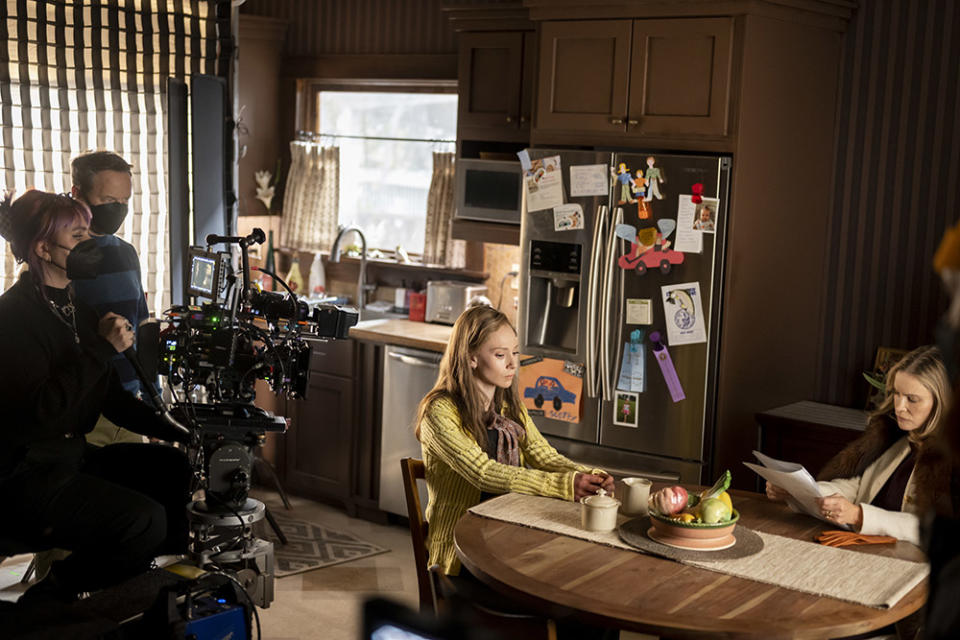

The distance certainly hasn’t impacted his output, which is prolific, nor his success. In fact, Fargo, which returns for a fifth season starring Jon Hamm, Juno Temple and Jennifer Jason Leigh on Nov. 21, has been nominated for 55 Emmys and won six. In recent years, Hawley, a third-generation writer whose twin brother, Alexi, is also a showrunner (The Recruit), has published a sixth novel (Anthem), directed a Fox Searchlight film (Lucy in the Sky) and readied another franchise adaptation with Alien, which he’s set on Earth 70 years from the present day. Zooming from Texas, Hawley opened up about a fast-changing industry and his place within it.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

How did you spend the strike?

I was in a very strange position. I was in post on Fargo and also in Thailand prepping Alien. I had all my scripts and I was the director of the first hour, and therefore couldn’t really walk away from that. So, I found myself walking a tightrope trying to figure out how to manage this process without wronging any of the interested parties. But my call sheet in Thailand, on the biggest day, had 765 people who I was employing, and everyone’s got families and they’ve got to eat. And so as long as I’m following the rules of the guilds, I have to keep going.

You ultimately did shut down production, no?

I had a majority equity cast, and so FX asked me or told me to shoot the equity work in the first hour. When that was done, rather than jump to the next episode’s equity work, we shut it down.

Back in 2016, you said, “What success has done is present me with a lot of opportunities, and I haven’t necessarily learned to say ‘no’ as well as I should have.” Seven years later, how are you doing with “no”?

I’ve gotten better at not jumping on every incoming call, certainly. I don’t feel like I’m much better at managing the number of ideas that come into my own head, but I’ve learned a lot about how to manage my time. And the thing I’ve become most aware of is that I’m just not available between Fargo and, now, Alien. And my plan is to make another film, where that fits and what that is, these are conversations, but I can’t really do rewrite jobs, and that’s great, I’m in the position where I am telling the stories that I want to tell. I think the “eyes are bigger than my stomach” phase of my career is over.

What had been driving all of the “yeses” before?

You work so long in this business as a freelance artist where you say yes to everything because you don’t know if other offers are coming. And also, when you’re in that freelance stage, most things don’t get made. Then, around 2016, I realized that if I said yes to it, it was going to get made, so then you have to be really careful about what you say yes to.

How did you land on the premise for the new season of Fargo?

Every time I finish one, I don’t know if there’ll be another. But here, some of it was timing. We wrapped the fourth year of Fargo in August 2020, and I knew I wasn’t going to be able to film Alien until 2023 and it won’t air until 2024. So, I had this window to make a Fargo, and that motivated me to go, “OK, well, what?” I went back to the original film, and it’s such a compelling moral dilemma story, and the characters are so great, but I found myself focused on Bill Macy’s wife. It was such a great performance, but once the bag went over her head, that was it for her. I thought, “What if the bag never goes over the head? What if she’s not kidnappable and there’s a backstory there?”

It opened me up to explore this concept of “the wife.” I found this great New York Magazine piece from the 1970s where this woman wrote this essay called, “I Want a Wife.” She wrote about all the things that she wanted a wife to do for her. I thought that was really fun to play with, as well. And I thought that given that every year the show, for me, is primarily female in identity, because the movie was Marge’s story, when you think about it, that would be a really powerful place to land.

You and your twin brother, Alexi, are third-generation writers. If I’m not mistaken, your mother was a journalist and activist, and your maternal grandmother was a playwright …

Yeah. My grandmother worked for Walter Lippmann, at The New York World, and she had an eighth-grade education. And my mother [Louise Armstrong] never went to college. And these two women both had careers as writers. My mom wrote a lot of nonfiction books about some very difficult subjects, including domestic violence. This season of Fargo is very personal to me because it explores this sort of taboo subject of domestic violence and trauma in general and the way that people who have been victimized are made to feel and the way that in America we often blame victims.

So, I felt a real responsibility in telling this story to do it accurately and in a way that wasn’t a melodrama and didn’t create fresh injuries for the audience. I wanted to make people feel empowered. When my mom wrote the first Speak-Out on Incest, and she talked about being an incest survivor, that was a very political term to her. It was like, “I survived it and now I’m on the other side of it,” and then the self-help business came along and said, “No, no, no, survival is this lifelong thing and, here, buy this thing.” So I think the anger and the triumph of overcoming the trauma of it is important. It can’t just be like, “Everyone needs a hug for the rest of their lives.”

Is FX already banging down your door for another season?

No, they’ve learned that if they just leave me alone, I’ll come up with something. But I will say that I feel reenergized on the Fargo front. It’s this crime genre with this absurdist element and philosophical streak that also is about basic human decency and an exploration of what it means to be an American, and how we’re all worse off for the forces of American capitalism that destroys so many, and I’ve yet to feel like I’ve tapped out of that world. You can be attracted to shiny new things, but I don’t know that I could get it better than this.

A few years ago, you told me, “What I’ve found with the franchise stuff, which I’ve flirted with, is that people don’t have a good sense of humor about that stuff the way they do when there is less money involved. So, I’m trying to figure out, is it worth pushing that rock up the hill.” Where did you net out?

I’ve been at FX for a decade now, and worked with John Landgraf for years before that, so everything I said in that interview is true with the caveat that when you find the right partner and they ask, “Do you want to do Alien?” — which is a hugely valuable franchise to this company — it’s, “Do you want to do your version of Alien?” It’s a very different conversation. What I found with Star Trek was I got onto the runway and then there was a managerial changeover. In retrospect, it’s not that they killed the movie. It’s that I got as far as I did with a wholly original idea, until someone said, “Well, wait a minute, what are we even doing with this valuable IP? Just giving it to him to make up a story? That’s not how corporate filmmaking works.” So, if the call came in to do a big franchise film again, it would have to come with a sense of, “We want you to do your version of it.”

Can you really trust that? You’ve been in this business long enough to know lots can happen in the process …

Well, it depends. I mean, there are enough examples to seduce us into thinking that it’s true, right? You see Thor: Ragnarok, and you’re like, “Nobody told Taika [Waititi] what to do with that movie,” right? Or James Gunn and the Guardians movies. That said, both of those filmmakers and those films are hugely satisfying on an emotional level and accessible in a way that the companies are thrilled to have them. But yes, the battlefield is littered with the bodies of the Lords and Millers on Star Wars who tried, and then the corporations were like, “What are you doing with this?” It’s like, “I’m having fun. I’m playing because they are action figures that we’re supposed to play with.”

Is helming a Star Trek or Dr. Doom or even X-Men still of interest?

There was a sense in the early days of Fargo and Legion that there was still something to prove, and that there was a tier higher that I could climb to. Now, I don’t really think that tier is a real thing. If you’re doing the work that you want to do and they’re paying you to do it, that’s the highest tier that you can reach.

You were being deluged with accolades for Fargo …

But that was the thing. I had two shows before Fargo for ABC [The Unusuals and My Generation] in which greatness was not really possible because what I thought was great and what they thought was great were two different things. Fargo was the first time I was able to go, “This is the best show that I can make,” and I was rewarded for that. I was told by FX and by the audience and the marketplace and the awards that, “Yes, we agree that your best is best.”

So, the challenge is always, if you’re going to say, “I want a $200 million movie,” is that still true? That what I think is best is best? I don’t know if the powers that be in Hollywood were angry about the success of Everything Everywhere All at Once by my friends, the Daniels, but I perceived them to be angry because it’s such an unrepeatable phenomenon. There’s almost no lesson that you can learn from the success of that movie that can be applied to other movies. There’s no formula, and everyone’s looking for a formula.

As you said, you had a partner in Landgraf who said, “Make your version of Alien.” So, what have been the challenges of doing that?

There was a challenge early on simply because this process started in a pre-Disney Fox, and then became a Disney Fox, which was Bob Iger, and then Bob Chapek and now Iger again, and there was definitely a moment in which it felt like, on a corporate level, the people who make the creative decisions are different than the people who make the financial decisions and there was a lot of internal pressure that the show should do a specific thing or not do a specific thing.

How did that get communicated?

It was doubt. There was an element for my partners of having to navigate an org chart that was trying to take some creative power up to the next level in a way that makes it harder for artists. That said, it was temporary. We’re not in that moment now, but I think that was part of what extended the development period.

What is Ridley Scott’s involvement in the TV show? Having directed the film, is he involved?

I mean, are the Coens involved in Fargo? Let’s just say, I’ve probably had more conversations with Ridley than I’ve had with Joel and Ethan. Scott Free [Productions] is producing Alien and Ridley is making two or three movies a year is basically how that’s working. I mean, Ridley has been an amazing collaborator to the degree that I can pick his brain about all of his thoughts, processes, decisions and the things that he’s learned. And I try to keep him [in the loop] and send him material so that he feels respected and included. But also, he’s doing his thing.

You’ve now written and directed a film with 2019’s Lucy in the Sky. I’m curious how that experience compared to those in TV and what you learned in the process.

I did not have a great experience on that film, unfortunately.

How so?

I have this joke every time I go somewhere new, which is, “I’ve got to train these people now on how I make things?!” Because I have a process that I go through to create hopefully unexpected stories with emotional power that doesn’t necessarily follow a formula. The problem with trying to do something original and not following steps that are familiar to people is that they don’t get it necessarily until they see it. I like to say I’m in the “trust me” business, and that’s a harder sell. In retrospect, the movie was bought and set up as a Reese Witherspoon black comedy, and there must have been some extent to which Searchlight was expecting it to be that, and I delivered my magic realism astronaut movie [with Natalie Portman]. They didn’t know what to do with that movie.

Do you feel like it’s impacted your ability to make more?

I haven’t noticed that. I think we all understand the forces at play. My job is to make the best movie that I can, and then the studio’s job is to promote it and do the festivals and all that stuff. If they don’t do that, you can’t really blame the filmmaker.

There have been a lot of conversations about budget-tightening in TV and an industrywide correction. What has that looked like for you?

You have to know the moment in which you’re working. When I started with Fargo and then got into Legion, the budgets got bigger. We started out on Fargo, season one, with $3.6 million or something crazy [small] like that. And Legion, I don’t remember the numbers, but they weren’t Game of Thrones money or Netflix and Amazon money. But I was being asked to compete with those places for awards and viewers, and so I said in that moment to FX, “You’re asking me to compete with some very deep pockets, and what it costs can’t be my primary concern.” And, also, “What you want is for me to be ambitious for you, so you tell me what the number is and then I’m going to push you as far as I can to make a great show.”

Having come into my own on Fargo and then expanding to Legion and Lucy, I went through my experimental filmmaker phase and landed on the other side and I don’t have anything else to prove. I just want to tell great stories. So, I was very aware with Fargo [season] five, and now with Alien, that it’s a different landscape — it’s not expanding, it’s contracting, and the time to be pushing for more money is not this moment. In this moment, my job is to figure out what the real number is, and I’ll make it for that price, if it’s possible. The producer hat is very important to me.

Back to the WGA strike. Your name surfaced in the press as somebody who was eager for it to end. What did that entail behind the scenes?

All I was ever trying to do was ask a question.

Which was what, exactly?

Find out what was going on. That was my goal on day one, and that was my goal when Kenya [Barris] and I and others who either were named or not named were having these conversations. It was simply, “How can we help?” We have a unique union in that we have a large majority who are workers, and a substantial minority who are bosses who employ not only the members of our own union, but the rest of the town. And a lot of us take that leadership role very seriously; we’ve been given this responsibility for others and we can’t just sit back because either we’re still getting paid or we’ve been paid so well that it doesn’t hurt us financially and just go, “Well, they’ll figure it out,” if we feel like this thing could be a day shorter. No one was going to the leadership saying, “Mutiny!” or, “We have a new plan.” It was literally, “Hey, can we get in a room and hear what’s going on?”

How do you feel that went over?

I think there was a fear that if the studios found out the showrunners were asking for a meeting, that that might lengthen the strike, but that’s not an excuse not to talk to what is basically a tier of your membership that understands these studios and the people who run them because we work closely with them. My job is to try to get these corporations to spend more money than they want to on things that I think are funny or stupid or whatever. So, creative problem-solving. Anyway, it became a public thing, and then the leadership went back in the room and made a deal and that’s great. I didn’t need my meeting as long as we had a deal. What I’m happiest about, other than the fact that we can get people back to work, is that it didn’t become some membership civil war. None of us were tarred and feathered for simply asking the question.

A version of this story first appeared in the Nov. 16 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter