"With no disrespect to Cliff Burton, I think my picking brought a new tightness to Metallica. Cliff's sound wasn't very defined": An interview with Jason Newsted on the release of The Black Album

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

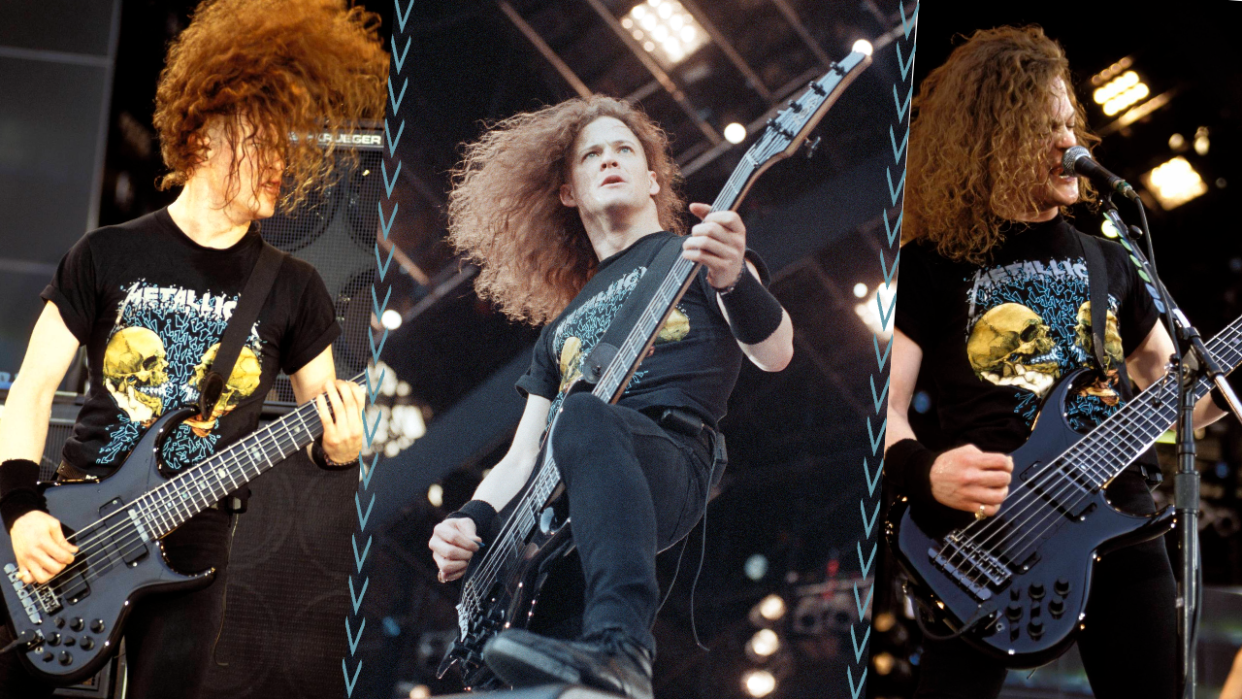

In August 1991 – three years after their last album …And Justice For All, and five years after the death of Cliff Burton – Metallica were gearing up to release another album. It was an interesting moment for anyone with an interest in Metallica and bass playing: …And Justice For All had featured very little audible bass.

Looking back in 2022, Newsted told Metal Hammer that he was “fucking livid” when he heard the final mix of the album. “Are you kidding me? I was ready [to go] for throats, man! I was out of my head, because I really thought I did well. And I thought I played how I was supposed to play.”

In the years following its release – and Newsted’s departure from Metallica in 2001 – the album’s lack of bass became used as a symbol of the dysfunction within the band as they struggled to deal with the death of Burton and failed to integrate their new band member.

In 2008, drummer Lars Ulrich denied that there was any malice involved in Newsted’s parts on the album being buried to the point of being scarcely audible. “No, it wasn't intentional,” he told Decibel magazine. “Justice… was the James and Lars show from beginning to end, but it wasn’t, ‘Fuck this guy — let’s turn his bass down.’ It was more like, ‘We're mixing, so let's pat ourselves on the back and turn the rhythms and the drums up.’ But we basically kept turning everything else up until the bass disappeared.”

Touring the album, the band worried that they had gone too progressive – that their music had become too complex and self-indulgent. Guitarist Kirk Hammett commented that from the stage he “saw people literally yawning, checking their watches”.

“When it came to the next album, we didn’t want to go down the same progressive, demanding route,” said Hammett..” We had our sights set on bigger things. You have to remember that there had been some mega albums around that time – Bon Jovi, Def Leppard, Bruce Springsteen… eight million, nine million copies sold. And we wanted that. It’s obvious. We wanted a Back In Black.”

The album, called Metallica, but known everywhere as ‘The Black Album’, fulfilled the brief: to date, it has sold more than 30 million copies worldwide. Back in 1991, ahead of its release, Bass Player’s interviewer Karl Coryat commented that the album was "radically different from its predecessors. Ask any Metallica member what the biggest factor is, and he'll tell you it's bassist Jason Newsted's new approach to his instrument.

"Lead guitarist Kirk Hammett puts it this way: 'Jason is getting more to the core of a traditional bass playing role: holding down the rhythm with the drums and adding a good foundation for the guitars. He's gotten rid of the idea that he needs to trick out all the bass players of the world with fancy lines. On the new album, he plays really well, and his tone is great.'"

Here is the interview, first published in Bass Player, Sept-Oct issue, 1991.

How is the album different from previous Metallica records?

Our last record […And Justice For All] had too dry a mix. We wanted it to sound good for everyone whether they had a cheap car stereo or a $3,000 system-but we went too far. There was hardly any bass; I was mostly just doubling the guitars, so there didn't need to be much. That's how it had always been in Metallica: most of the time I'd be doing the same picking with the same power as the guitars, so the sound was almost one-dimensional.

On this record, we're actually a band, and you can hear bass. The producer, Bob Rock, made a big difference. We chose him because the projects he'd done before, like Bon Jovi's Slippery When Wet, are really great and have big bottom end. On this record, I’ve concentrated on getting a big bass and the fullness of a real musical band – the 3-D sound. You'll be able to tell it's Metallica within the first tenth of a second. The powerful, fast stuff is there. But most of the album is mid-tempo songs, a little like Harvester of Sorrow [from Justice] l except that I really play bass, and the guitar does the guitar part and so on. I learned a lot making this record.

Why is that?

In Metallica, I've been a pretty aggressive bassist. But sometimes I'll get together with friends to pIay blues, and I'll do the round-and-round, 15-minute, blues-bass thing. But whenever I played with Metallica, it was always fast stuff. This time I learned about playing bass with Metallica. At home, I listen to a lot of Motown and Earth, Wind & Fire, and when I record my own tapes I play real bass. I finally realized that even in Metallica, the bass has to be with the drums as a rhythm section, not a guitar-and-drums rhythm section, which it used to be.

When I first joined, it was weird – I was used to Flotsam & Jetsam's bass-and-drums sound, with the guitars doing whatever on top. The new Metallica is more like that, and it's much better. I'm not playing a thousand notes a minute; I'm learning to lay down the bass – the real thing, not just messing around.

A lot of fast players think that [sings slow eighth-notes] do-do-do-do-do-do-do-do is cake. That's total bullshit. I've learned there's nothing easy about laying down a line with exact consistency- being right there, in the pocket. Some people wilI think, 'Oh, what have they done to Metallica?' but I think most people will see we're growing and maturing. Real bands – like Rush, Led Zeppelin, and Black Sabbath – progress and grow, they don't just do the same album over and over again.

Are you worried that some of your fans will reject the new sound?

The press is already condemning us – they're wondering what will happen to our "street cred." That's a bunch of shit, because Metallica has never worried about what people think. We've always played what we’ve wanted to play, and if people didn't dig it, that didn't matter to us. It so happens that people like our music, and we're doing well: what's wrong with that?

Now people are condemning us before they even hear the music, just because they've heard we have songs with cellos and nylon-string guitars. People who give it any thought, though, will be happy for us. There's no question we'll gain a ton more listeners than we'll lose.

The thing is, MetalIica had pretty much gone to the end. How many more parts and time-signature changes can you have in a song? This time, we're doing a Sabbath thing: catch on a couple of riffs and go with it. Move them around a little, move the drum parts around a little, and add a cool-ass vocal riding above it. We've already done the billion changes, so we're taking it to the next step. A lot of people will be surprised.

How did the songs come together?

The songs were all written before we went into the studio. We started sifting through our demo tapes during the summer of '90, and James and Lars put everything together. By September, when we started rehearsing, the songs were pretty much figured out. We changed a few parts, but 90% of the music was there.

How long had the demo tapes been in the making?

Some of the material comes from as far back as Ride The Lightning – before I joined. That's how we work. I submitted a bunch of songs, but My Friend Of Misery was the only one we ended up using, mostly because James comes up with the killer stuff. Our problem – and it's a good problem – is that we have trouble throwing stuff out. We have so much to pick from; everybody submits an hour or an hour-and-a-half of demo tapes for every album, and stuff that doesn't get used on one album might end up on the next. When we make our next record, we'll have material left over from all five albums to pick from.

How did you write Misery?

I wrote a riff and put it on tape. When I gave the tape to Lars, he said Sabbath had done it! The riff was similar to something from a Sabbath tune that I never knew, Supernaut [Black Sabbath, Vol. 4]. So Lars told me to write something along the same lines with the same mesmerizing D-minor sound [mimics Spinal Tap's Nigel Tufnel] "that makes people weep instantly – something angelic" [Laughs]. That turned into the intro and the instrumental refrain of Misery, and I stretched out the song with a riff I wrote on guitar. Lars and James then twisted it around, and finally James wrote the words and the melody.

Your playing on Sad But True recalls your earlier style: doubling the guitar riffs.

That was required for the song: it needed to be there. We tried several different things – all eighth-notes, or a bop here and a bop there – but it just wasn't happening. When we played the song, everyone would put in their two-cents worth on how the bassline should go, and in the end we decided I should just double the riffs.

When you were recording the album, how did you treat the bass?

Bob Rock had me try about 25 different basses and a bunch of rig combinations. We tried some Trace Elliot stuff – which is what I've been using live – and also some Ampeg, Crown, SWR, MESA/Boogie, and ADA equipment. We had all these rigs next to each other and we could combine them various ways, which was cool. I ended up using my Trace GP11 preamp with a direct line, SWR SM-400s for lows, original SVT heads and 8xl0 cabinets for mid rumble, and old Marshall guitar cabinets for mid-highs. We mixed all of those together, and the mix was different for each song. On the slow tunes, we mellowed out the bass by adding more of the SWR and SVT; The Unforgiven was mostly SVT with a little direct. For angrier songs like Holier Than Thou it was pretty much an equal mix of everything blasting, with a little extra DI.

Which basses did you use?

I ended up playing an '81 Spector [4-string] for all the songs except The Unforgiven which sounded best with a '59 Precision.

Did your studio playing change because of the new sound?

I definitely played differently than I did on either of the last two records. But I don't think that's because of the sound; I tried to be aware of an exact picking area – right over the pickup – using consistent hits. When we recorded before, I'd just blast through stuff; now, I'm more conscious of laying down a good bass line.

On Justice it sounds as if you were having trouble fitting into the mix.

I was. The sound was okay, but it would have been more appropriate on a pop song with a slap bass line. It didn't hold a lot of the bottom end, and it was just swallowed up by the guitar tracks.

Were you satisfied with the mix at the time?

No, not at all. When it was time to record, I just came in with my live rig and played. I went through an ancient G-K 250 head and an SVT cabinet; we miked the speakers and added a few direct lines, and then we mixed the two. We were clueless about how different frequencies work in a mix, and we found that if we brought the bass up it killed the guitars. Now, it's different because we understand frequencies: I learned that by using combinations of the different amps, I could fill the spaces in the frequency spectrum. I used to cut out all the mids – but that's also what Kirk and James do – use mostly just lows and highs. So I learned to develop all the mids, from low mid to high mid, which makes my sound stronger and more supportive for the guitars.

How many basses do you own?

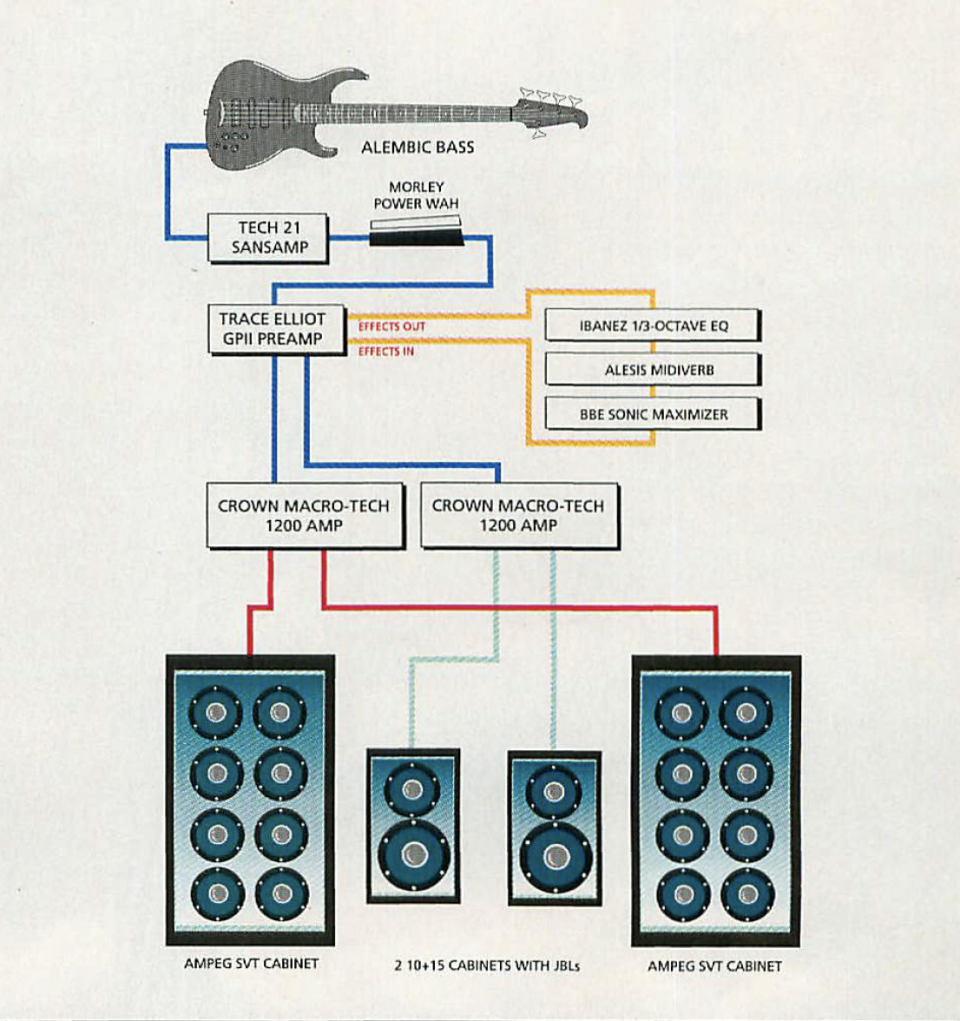

A lot. I've been collecting for a few years, and I have about 70 instruments now – mostly old ones. I have about a dozen Alembics; those are my live instruments and I take a lot of pride in them. Onstage, I use primarily 4-and 5-string Alembics that are similar. It's pretty much my own design: all-maple, with two Alembic J pickups and a P in the middle, a volume control for each pickup, and a master tone control. I usually string them with LaBella roundwounds, gauges .46, .66, .86, and .106, with a .128 B string.

Why do you use a J-P-J pickup configuration?

I like the fullness of P pickups; I use the J's for a little more low boom and a little more high click. On my Alembic basses, even when everything is on full, the P pickup produces the majority of the sound; the J's add just a little extra.

On how many songs do you play a 5-string?

About three out of four. I prefer the 5-string, because the guitars cover so much ground from low to high; I have to get way down below their ranges just to be heard. When we were recording this album, the basses I settled on were 4-strings, so when I had to play a part that went below E, I re-strung with the bottom strings of a 5: B, E, A, and D. Because of the tension, I had to mess with the intonation, but it worked well. I can't do that live, so I play a 5~string on songs that require the extended range.

Do you have any problem switching between the different string spacings?

No. Once I get going on a song, I don't even notice the string spacing.

How long have you used a pick?

Always. When I started, it was the most comfortable way to play, so that was it. All along the way, though, people have hassled me about it: "When are you going to become a real bass player?" I can play with my fingers, but if I hadn't learned to play with a pick, I don't think my playing would be quite as decisive or effective for Metallica.

Cliff Burton played with his fingers.

Right, but he was an extraordinary player, and he had this huge grumble thing going on live. Plus, he was an incredible soloist – that was his forte. But with no disrespect to Cliff, I think my picking brought Metallica around to a new tightness and unit strength. Cliff's sound wasn't very defined, especially when he was playing low on the neck. As I've improved my downpicking, Metallica has developed into a tighter-sounding band, both at the bottom and the top.

How much chording do you do?

A little, but only on songs where chords are needed. I can get carried away with chords onstage, but I think single, booming notes are most effective, Sometimes I'll pick an octave or a crunching fifth, but since the guitars are so big and cover so much frequency area, I've found that single notes punch through best.

Have you developed any special tapping or harmonic techniques?

No. That's just not my thing; I'm pretty much an orthodox player. I'm not against special techniques – if I took some time to figure out something, I'd be pretty proud of myself. But if I'm going to try something new, I'll do it within my style. My thing isn't jumping out front and tapping; it's hitting the string real fast [laughs]. I do like to add vibrato and string bends for color, though.

How did you get into music?

There was always music around; my parents and my two older brothers played records all the time. This was in Niles, Michigan, so we listened to a lot of black music – Motown, Jackson 5, Earth, Wind & Fire, that kind of thing. As I got older, I started getting into bands like Kiss, Foghat, REO Speedwagon, and Ted Nugent. Then Black Sabbath came along, and then Rush, which was a huge influence – Rush was my favorite band for years. I really looked up to Geddy Lee.

Did he inspire you to start playing bass?

It was more Gene Simmons; he was it for me. My friends and I wanted to be Kiss - just like all the other kids at that time. I liked Simmons the best so I got a bass: a Kay SG-lookalike with a Gibson amp. I never played it, but I'd go [plays a swooping slide up and down the neck] a lot. I didn't know how to tune it or anything, and I put it in the closet for about five years. When I was in high school, I picked the bass up again and started messing with it; I didn't really dig anything at the time, so I was searching for something to get into. I started jamming with some guys, and it grew from there.

Were you entirely self-taught?

Yes. I took one lesson when I got my bass, because my dad said I had to. But after that, I was on my own. I jammed along with Gene Simmons a lot; Parasite [Hotter Than Hell] was my favorite tune. F# rules! You can come from anywhere - start at A# flatulent, come down to that F#, man, and you're there!

Who were some other influences?

Geddy Lee, Geezer Butler, and Rob Grange with Ted Nugent. Grange was underrated as a good bass bass player.

You said listened to a lot of Motown. Did you ever work out James Jamerson's parts?

No, I'd be dreaming. His vibe was just too incredible; he was a hugely gifted person. I learned My Girl because that was pretty easy. But even his simple lines sounded great because of his feel and command of the pocket.

When did you decide to turn pro?

I was 18; I had become a hoodlum, and I quit school to play in a rock band full-time. We decided to leave Michigan and head west in a U-Haul – we just drove blindly, with all our shit in the back. We ended up in Arizona on Halloween of 1981, exactly five years before I joined Metallica.

The band split up almost immediately. I got a job, bought some better gear, and early in '82 I hooked up with a drummer, Kelly Smith; we formed Flotsam & Jetsam. We played clubs in Arizona for the next three years while changing members. We did demos in '84 and '85, landed an independent deal with Metal Blade in '85, and put out our debut album, Doomsday For The Deceiver, in '86. The album had been out for three or four months when I was asked to join Metallica.

How did you hear that Metallica was looking for a bassist?

I heard that Cliff had died the day after the accident. I was pretty much blown away; I was a huge Metallica fan at the time. When I was looking at the blurb in the paper, I was sad but things started flashing through my mind: I started thinking, "Metallica-wow, jeez…" I got in contact with Michael Alago, who had signed Metallica to Elektra; he told me the band was holding auditions, so I called them up. I wasn't expecting to get the gig; I just thought if I could play Four Horsemen once with those guys, I'd be really happy.

I was a little down on Flotsam – everything was rolling with the album, but I felt like I needed a boost. It turns out Lars had been scouring everywhere to find guys to come out and audition, and through the people I'd been hounding about Flotsam, my name kept coming up. Brian Slagle from Metal Blade had sent Lars a package of Flotsam stuff, so Lars was pretty hip on me.

Metallica gave me some extra time to get ready for the audition. I learned as many songs as I could in the space of a week; I barely slept. I found out what their set list was from the previous tour. When I got to the audition, I handed them a sheet of paper with all the songs on it, and they said, "Wow, this is our set list."

So I hung out all afternoon with them and played a bunch of tunes. Lars called me that night and asked me to learn some more songs and come back in two days, so I did. Afterwards, we went out drinking, and they asked me to join the band. I was totally blown away, and for a while I couldn't believe it had happened. We rehearsed for five or six days, played a few clubs in southern California, and flew off to Japan to complete the Puppets tour.

Was it tough trying to fill Burton's shoes?

I didn't approach it like that – it wouldn't have been possible. You can't fill the shoes of someone who was, for our kind of music, a legend in his own time; you have to go into the band and be yourself. The other guys did drop subtle hints here and there, though.

They never told me directly what I should play; they wanted me to learn and grow and realize it myself. It took me a while, but I caught on.

There were times when people thought I was trying to be Cliff. It was hard not to be influenced by him, and certain songs had parts of his that just had to be there. At shows, kids would come up to me and say stuff; usually they were positive things, but not always.

Sometimes, I'd get some real animosity: kids would say, "You're never gonna be as good as Cliff - what the hell are you doing here?" That was the biggest thing I had to deal with, but I pretty much knew what I had bargained for. It all worked out - after five years, I've developed my own style, and now I'm the bass player of Metallica.

What advice do you have for young bassists playing metal?

Play bass. There are times when you need to double a guitar riff to make it a stronger-sounding figure, but usually you need to let the guitar players do their work while you hold down the low end. Everyone wants to be flashy and to play real fast – I still love to play a million notes a second – but when it comes right down to it, there's a time and a place for fast playing. You have to feel the song out. If it's a song where you should lay back, no matter how much you want to jump out front and flash, you have to be the bass player. And if you're going to be a bass player, you have to play the bass part.

There's a million guys out there who can do 17-finger pull-offs with no problem. I have respect for that, and it's great for a solo situation. But when you're doing that all over a song, it's not bass playing. You have to think about music – like blues, or an old Motown tune, where everything rides on the bass. With an approach like that, if the bass is there, everything will be okay.

The bottom falls out when you go up high and do some tweedling when there's no need for it. If you come to the bridge, it's great if you can get in with the guitars and play the harmony or some dissonant part that adds flavor or color or weirdness – but overall you should play bass.

Jason Newsted left Metallica in 2001 and played for his band Echobrain. He joined Voivod in 2002 and played with Ozzy Osbourne, reality TV show supergroup Rock Star Supernova, and his band Newsted. He has played with bluegrass band The Chophouse Band for 30 years. This interview first appeared in Bass Player, Sept-Oct issue, 1991.