No. 7: Emerging Chef Josmine Evans is griot, grower, damn-good cook at Indigo Culinary Co.

As owner of the pop-up Indigo Culinary Co. and co-owner of Detroit-based garden The Joy Project, Josmine Evans comes in at No. 7 among the 2023 Detroit Free Press/Metro Detroit Chevy Dealers 10 Best New Restaurants and More. Evans is this year’s Emerging Chef.

To be in conversation with Josmine Evans is to embark on a journey.

Like a high-powered vehicle, her words are transportive, swiftly ushering you through locales, decades and more often, cultures.

As a storyteller who pairs her words with soulful dishes through the Detroit-based pop-up restaurant Indigo Culinary Co., Evans has made it her profession to deliver clear narratives to her clientele.

Eat Drink Freep: Sign up for our new food newsletter!

Stories of her family lineage are specific with names and memories that date back to childhood, and when she shares the accounts of her travels across the globe, you can almost taste the spices in the dishes she ate, follow the stops she made down to the timestamps on the itinerary that guided her. Language, she says, is an important tool of her process.

With respect to her professional title, though, the words escape her.

Between eloquent reflections on her family history and concise breakdowns of culinary routes from Africa to the American South, the best description she has for her own work is, “I do food stuff.”

Even for this wordsmith, there is no one term to encompass all that Evans does, and the vocabulary that exists for some of it can be rooted in systems that are antithetical to her work. The term, “chef,” for example, represents the pinnacle of a culinary hierarchy often achieved through schooling, networking opportunities and financial resources that can be out of reach for some people of color — the very people Evans’ work aims to support.

Evans' work is better defined through interaction.

During a recent event at Detroit art gallery The Scarab Club, Evans and partner Gabrielle Knox led a hands-on workshop on cotton, a crop being grown at The Joy Project, the North End garden the co-founders consider a living archive of African Atlantic agriculture and foodways.

Menus for Indigo Culinary Co. pop-ups are typically layered on top of old family photos, and on social media, Evans offers historical context for the photos and the dishes they’ve inspired.

It’s in Evans’ favor that the current moment is supportive of the multihyphenate whose titles are mouthfuls of slashes and ampersands. She’s a cook, a farmer, a cultural anthropologist, an educator and a storyteller. But the through line across all of Evans’ work is cultural preservation. Her functions at the garden and at Indigo Culinary Co. aim to resist the erasure of Black foodways and the contributions of Black and Indigenous people of color throughout history.

“A cultural preservationist is invested in living archival work in which you are collecting stories, traditions and knowledge of culture and sharing it with other people,” she explained.

Evans looks to examples in history when people in positions of power have separated marginalized communities from their cultures, beginning by displacing them from their homeland and loved ones, and cutting off access to their ancestral foods.

“Preserving that culture is a way to reconnect for our health and well-being," she said.

Evans, the cook

Evans’ childhood was rooted in handiwork. Family bonding centered on domestic chores, such as housecleaning, construction and gardening. At an early age, Evans became the designated home cook.

“The person who makes the food has been a part of my identity, at least, since the sixth grade,” she said. That identity followed her into adulthood.

Eventually, food became the tool she’d use to share her identity with others and ultimately, to redefine her identity for herself.

“My attempt to share the stories of who I am and what's important to me, happened a lot over food,” she said of her earliest days living in Detroit.

She’d relocated to the city in 2014 with her then-partner and experienced a homesickness that comes from being starved of the familial ties she’d been tethered to her entire upbringing in Oakland, California.

As she spooned heaps of red beans and hot sausage into bowls for dinner, she’d share stories behind the dish with her partner — her Auntie Carol taught her how to make it.

“Whatever I cooked, I’d be sharing those stories to try to get my ex to understand that I was struggling," Evans said.

The challenge of being isolated from loved ones was compounded with existential questions that began surfacing for Evans.

“It was one of the first times I started seeing myself as an individual,” she said. “I was trying to create an identity that wasn't dependent on being Hank’s daughter or Carol's niece. I’d always been a ‘we’— now, who is the ‘I’?”

Soon, cooking for Evans turned from an explanatory process to an exploratory one, prompting her to trace the roots of her foodways. She explored the differences between red gravy in the seafood dishes prepared by her patriarchal family from Louisiana and the meat-forward meals basted in brown gravy on the matriarchal side of her family from Virginia.

“I learned the difference between the plantation cultures in English colonies versus Spanish, French and Portuguese colonies,” she said. “The diets of my ancestors were influenced by their own traditional foods as well as the foods of their captors and colonizers and the local flora/fauna of whatever geographical region they were dispersed to.”

The gumbo Auntie Carol cooked in Oakland, she said, teemed with Dungeness crab, unlike the gumbo she was raised on in New Orleans, which featured blue crab meat, or the gumbo of the Carolinas — or the very West African okro soup that birthed all iterations of gumbos to come.

“I learned that my ethnicity wasn’t as simple as ‘descendant of enslaved African,’ but that my patriarchal lineage stopped through Haiti before landing stateside, which expanded my individual identity. While I am indeed this little Black girl from East Oakland, the blood in my veins has traveled thorough so many different places.”

Today, she shares those findings with diners through Indigo Culinary Co.

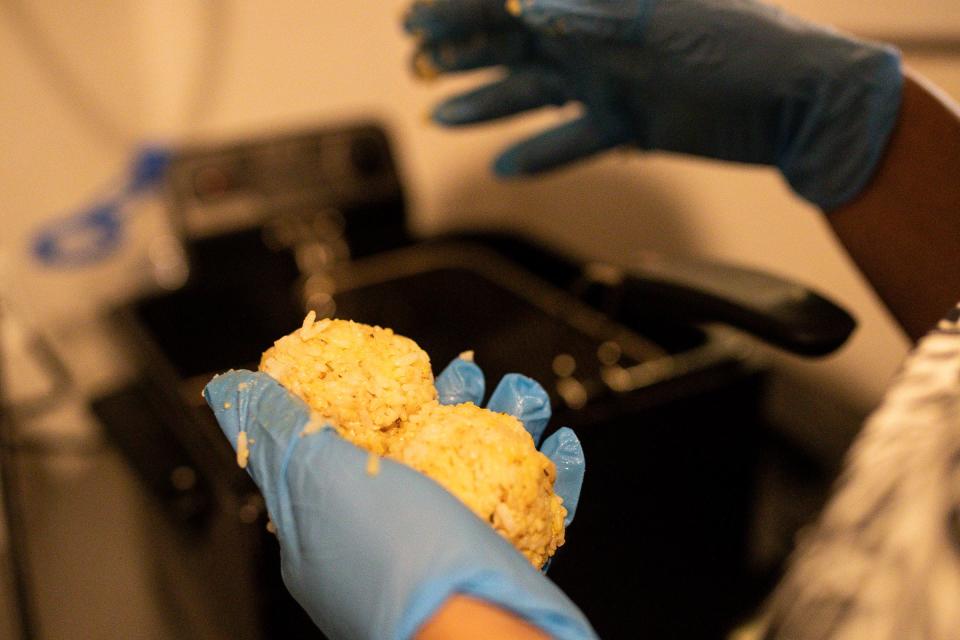

At Two Birds, the West Village craft cocktail bar Evans frequents for pop-ups, she’s offered her grandmother’s German chocolate cake, spread generously with a custard topping teeming with flaky shreds of sweet coconut and hunks of pecans. Her Mami Burger, an ode to the long line of women before her, stars a flavorful beef sausage patty seasoned with an old family recipe and earned my discerning husband’s stamp as the best burger in recent memory.

Evans, the educator

The meals Evans prepares are often simple. Corn soup and spiced popcorn, collard greens and artichoke dip and hot wings and sweet potato fries are among Indigo Culinary Co. menu highlights.

Unfussy dishes help Evans to educate diners on Afro-Atlantic foodways and the cultures that have influenced them over the course of history most effectively.

She’s illustrated the impact of slavery on European countries, such as Portugal, as context for dishes like feijoada, and explained imports of native African plants to the Caribbean, such as tamarind and plantains.

“I’ll feed just about anybody,” she said. What’s important to me is that the global Black community feels validated, seen, affirmed and encouraged to connect and reconnect with their foods, and feel good doing it.”

As Henry Kissinger famously said, “Who controls the food supply controls the people.” And according to Evans, “that includes the narrative around the food as well.”

Evans, the researcher

A world traveler, Evans considers her journeys a form of research, hands-on learning that offers her an opportunity to see the presentation of a dish in its place of origin.

Before “High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America,” the acclaimed 2021 Netflix docuseries based on Dr. Jessica B. Harris’ book “High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America” (Bloomsbury USA, 2012), Evans joined James Beard Award-winning culinary historian and author Michael W. Twitty for the food-based heritage tours to Africa depicted in the series.

“Michael Twitty and I see things from a very similar lens, and we engage with things from a very similar place,” she said.

Since 2018, Evans and a handful of culturally curious culinarians have traveled to Africa with Twitty annually. They’ve learned recipes for kenkey from a woman who specializes in making the fermented corn dough in Ghana, and participated in animal husbandry lessons in rural villages with minimal utilities. Travels to Benin and Togo, Senegal and The Gambia have followed suit, giving Evans and the participants the opportunity to learn from the agrarians and cooks preserving ancestral foodways in their regions.

When she returned from one of the trips, the weight of the opportunity inspired her to share the knowledge she’d learned with others. “I felt privileged to have the means to move about the world in ways that other people don't,” she said.

In the years that have followed, she’s hosted virtual cooking classes, held storytelling events and catered dinners.

“Detroit directs me to where it wants and needs me, and that is the type of relationship that I'm looking for.”

In March, Evans will again join Twitty and a group of notable culinarians on a trip to Cameroon, the birthplace of trip’s organizer, Ada Anagho Brown.

“ ‘High on the Hog’ brought publicity to these trips and now more high-profile folks are ready to have the experience for themselves," Evans said. "It's exciting to be going to this place with all these people that I admire.”

Evans, the grower

The living archival work of a cultural preservationist, for Evans and Gabby Knox, manifests in The Joy Project.

The duo hesitates to call the project a garden or a farm, but rather another safekeeping of sacred traditions.

“We have to be intentional about engaging joy because it's not just coming and finding us,” Evans said.

At The Joy Project, Evans and Knox cultivate plants that are native to Black foodways across the diaspora. Beginning as early as January, they’ve started seeds for Jamaica, or African Hibiscus, and Congo melons. Moringa trees have been planted in pots for an easy transition indoors once the warmer months have fleeted.

The four pillars that guide the site are reconciliation, restoration, remembering and recognition.

They’re growing crops like cotton in an effort to reconcile the Black community’s relationship with the plant.

They’re following growing practices, like no-till methods that are minimally disruptive to natural ecosystems, to restore damage that has been done at the hands of mainstream commercial agricultural farming.

They’re growing cultural foods, like callaloo, and varieties of chili peppers that are not readily available in many grocery stores but remind people of color of ingredients incorporated into their most nostalgic dishes.

They’re adopting practices, such as the Three Sisters method of planting corn, beans and squash in an effort to recognize Indigenous wisdom.

“That is the founding core of The Joy project, but it has since grown to provide space for a bunch of different functions that we never imagined,” Evans said.

Within months of acquiring the land with the assistance of the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund; a collaboration between the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, Oakland Avenue Urban Farm and Keep Growing Detroit; and their own crowdfunding of $20,000, Evans and Knox hit second-year goals.

Again asked “What do you do?” Evans replied: “My best,” she laughed, “I do my best.”

As the first Detroit Free Press/Metro Detroit Chevy Dealers Emerging Chef, her best efforts are well received.

Indigo Culinary Co.

Ticket sales for the upcoming Detroit Free Press/Metro Detroit Chevy Dealers Top 10 Takeover dinner series benefit Forgotten Harvest, an Oak Park-based nonprofit committed to fighting food insecurity in the Detroit area. Dates for the 2023 dinner series will be announced in March. Visit freep.com/top10 for updates on the events.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Josmine Evans is emerging chef at Detroit's Indigo Culinary Co.