'Night of the Living Dead' at 50: George A. Romero's classic remains as relevant, and horrifying, as ever

In the pantheon of horror classics, few stand taller than George A. Romero’s 1968 directorial debut, Night of the Living Dead. The story of a group of Pennsylvania strangers who find themselves trapped in a farmhouse surrounded by the undead, Romero’s groundbreaking indie never features the word “zombie” (its fiends are referred to as “ghouls”) and yet defined the reanimated creatures for the modern age, transforming them from black-magic Caribbean slaves (as in films such as 1932’s White Zombie and 1943’s I Walked With a Zombie) into rotting corpses with a single-minded hunger for human flesh — a legacy that shows no signs of abating thanks to the likes of 28 Days Later, World War Z, Train to Busan, Zombieland, and, of course, The Walking Dead.

A stark, brutal, and bleak tale of survival that shocked audiences upon its release, Night of the Living Dead imagines chaos and annihilation coming not from invading extraterrestrials or supernatural monsters, but from ourselves. It was a new apocalyptic American nightmare steeped in contemporary anxieties, and on its 50th anniversary (the dead rose on Oct. 1, 1968), it remains as potent — both in terms of scares and allegorical power — as ever.

Watch the trailer:

Shot on a shoestring budget, and inspired by Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, Romero’s 1968 saga is a sleek, stripped-down affair. While visiting their father’s grave, Barbra (Judith O’Dea) and brother Johnny (Russell Streiner) are accosted by a man who tries to take a bite out of Barbra. In a scuffle to save her, Johnny’s head collides with a gravestone and he perishes. Barbra, understandably freaked out by this incident, flees, eventually stumbling upon a farmhouse outfitted with an outdoor gas pump.

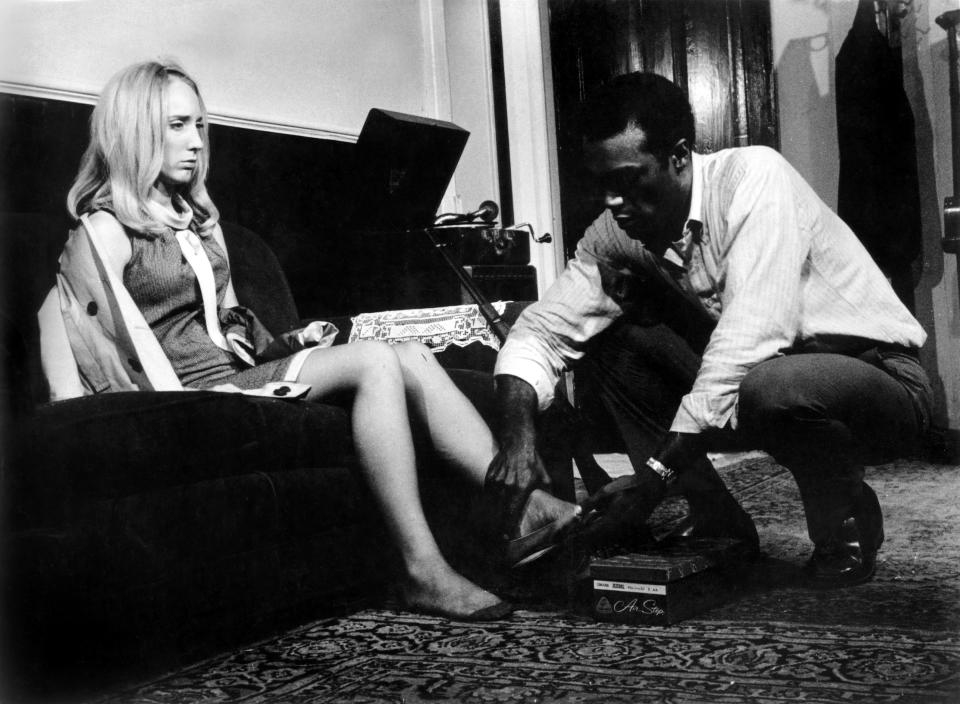

Struck nearly dumb by this trauma, she’s soon joined by Ben (Duane Jones), a tall, intelligent African-American man who promptly boards up the windows and doors. Before long, they discover they’re not alone — Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman) and his wife, Helen (Marilyn Eastman), have been hiding in the locked basement alongside their injured 11-year-old daughter, Karen (Kyra Schon), as well as local Tom (Keith Wayne) and his girlfriend, Judy (Judith Ridley). Such company quickly breeds hostility, as interpersonal frictions compound an already volatile situation — a setup that would influence countless progeny, including John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 and Frank Darabont’s Stephen King adaptation, The Mist.

Radio and TV news broadcasts reveal that this plague is spreading across the region (and perhaps the globe?) thanks to radioactivity from a downed space probe. Night of the Living Dead, however, hardly proffers that theory as a definitive explanation. Instead, it keeps the root cause of this cataclysm more than a bit vague, the better to maintain an atmosphere of dreadful, irrational uncertainty. Furthermore, it’s a strategy designed to leave things open to allegorical interpretation. Produced at a time of domestic racial and economic strife, as well as the Vietnam War, Romero layers the action with roiling undercurrents. From Barbra’s initial misleading dialogue with Ben (implying that Johnny was her boyfriend, which suggests she fears being alone with a black man), to Harry’s lies about his cowardly decision to not come upstairs and aid them (which are censured by Ben), to the “ghouls” themselves (which are simultaneously anonymous and familiar agents of death), the film is awash in all manner of urgent terrors and conflicts: familial discord; racial tensions; parental hang-ups; patriarchal hubris; and fear-of-the-“other” mania.

Take your pick as to what the destructive zombie hordes are meant to represent. They could be the liberal counterculture generation, intent on decimating the status quo. Or, conversely, they might be conservative America, striking back at late-1960s progressivism (after all, hero Ben is an African-American paired with a white woman — and Jones was horror cinema’s first African-American lead). Maybe they’re stand-ins for the Vietcong, making the proceedings a treatise on the folly of the country’s South Asian escapades. Given the ongoing Cold War, it’s also easy to see them as Russian invaders, here to wipe out America’s democratic way of life. Romero not only doesn’t say — he doesn’t overtly suggest any one reading. Instead, he allows them to be vessels of an open-ended nature, capable of embodying whatever fear is most front-and-center in the national consciousness at a given moment.

That means, of course, that from a 2018 perspective, one can just as easily view Night of the Living Dead’s zombies as — depending on one’s political persuasion — homegrown or foreign terrorists, invading immigrants or refugees, or MAGA-capped extremists. Romero’s first feature is always attuned to our darkest despairs, both narratively and visually. Employing stark black-and-white cinematography, the director crafts a vision of a world rife with contrasts. His chiaroscuro-steeped aesthetics, which include frenzied editing, convey a sense of opposing forces clashing in sharp, vicious ways. Meanwhile, his grainy monochromatic style lends the carnage a newsreel-ish realism which enhances its this-could-really-happen horror — and, consequently, reinforces the notion that the zombies are reflections of threats that exist in our here-and-now.

Nowhere is that more acutely felt than in Night of the Living Dead’s coda. After Ben has survived the zombie onslaught, he’s killed by a redneck sheriff’s posse, which mistakes him for another member of the walking dead. It’s a bleakly ironic final twist, and is followed by a montage of still snapshots of men using meat cleavers to throw Ben’s body onto a raging bonfire. That sequence’s imagery recalls photographs of wartime atrocities committed in the name of apparent maintaining-the-social-order good — and, moreover, feels intertwined with the film’s satire of the (misleading, if not outright exploitative) media.

It’s also, fundamentally, a traumatizing conclusion to a story marked by unflagging hostility and hysteria. And it’s one that helped cement the zombie as the 20th (and 21st) century’s signature creature. A grotesque resurrected version of mankind that cares only for cannibalistic consumption, Romero’s “ghouls” are us at our unholy worst, and the director used them — both here, and again in his stellar sequels Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Day of the Dead (1985) — to point the finger squarely at humanity for society’s failings. Rather than locating his mayhem in far-off Transylvania or remote Europe (or the tropical islands where zombies had traditionally dwelled), Night of the Living Dead brought the horror home — to our country, our houses, our very bodies. In doing so, it not only established a genre template that continues to flourish today, but set a lofty standard that’s rarely been met by those that have followed in its shuffling wake.

Night of the Living Dead will play in limited theatrical release on Oct. 24 and 25; check here for screenings.

Because the film exists in the public domain, you can watch it in its entirety below:

Read more at Yahoo Entertainment: