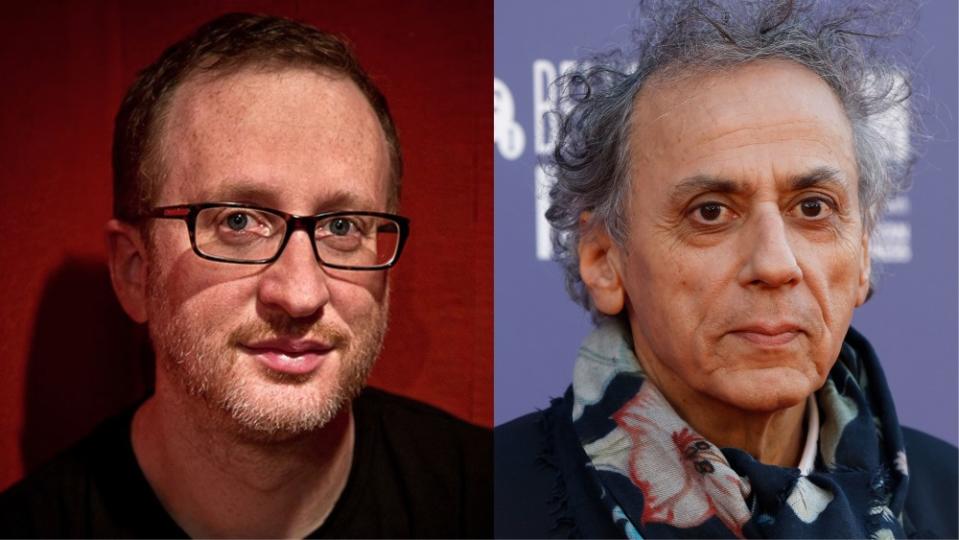

Nicholas Britell & Cellist Caitlin Sullivan

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Director Barry Jenkins knew he wanted brass instrumentation for his film adaptation of James Baldwin’s “If Beale Street Could Talk.” When his “Moonlight” composer Nicholas Britell started to share early recordings of the score with horns and trumpets, Jenkins was ecstatic — the music was the exact emotional texture he had been chasing.

But when Britell’s tracks were cut against picture, they fell flat. Convinced the melodies and harmonies weren’t the problem, Britell experimented with woodwinds, piano, and different types of brass instruments, but kept getting the same results. After Jenkins left Britell in New York to return to the editing room in Los Angeles, the composer spent a couple days experimenting with a different orchestration, this time with his wife, cellist Caitlin Sullivan. When Jenkins first heard the stem of Sullivan playing the “Beale Street” chords, he knew they had something special. “It was a really big aha moment,” said Jenkins. “The feeling we were conjuring had to be played on strings, and the really wonderful thing that happened was then the strings begot sounds that could only be played with brass.”

More from IndieWire

Britell remembers an emotional Jenkins calling from his car, insisting the composer put Sullivan on the phone so he could tell her how beautiful the recording sounded. Jenkins, who has referred to Sullivan as the “heart” of Britell’s music, joked, “It was never our intention to have as many strings on the ‘Beale Street’ score, but when you live with one of the great cellists of the world, you know these things have a way to happen.”

Two classically trained, New York-based musicians of the same age, Sullivan and Britell’s paths were destined to cross, except that they almost didn’t. Despite having graduated from Julliard as part of the same pre-college musical class of less than a hundred students, the two somehow never met during their school days. Sullivan likes to tell the story of how it was actually her mother who first noticed Britell, recalling how on their drive home from graduation she kept going on about “this amazing boy who was invited to speak at convocation, and how he showed up all of these faculty members.” For his part, Britell admits he noticed Sullivan at Julliard — she was already such an accomplished a cellist, everyone did. Months later they met while they were both students living in the same dorm at the Aspen Summer Festival, where they briefly dated before heading to separate colleges. Returning to New York City after their studies, they reunited, and were married six years later.

While their shared passion for music is what brought Sullivan and Britell together, they were a couple long before they were collaborators. Beyond Britell accompanying Sullivan on a cello sonata that first summer in Aspen, they never really played or recorded together. That started to somewhat change in 2009, when Britell invested in building a home studio. As the various mics and stands arrived, Sullivan would bring in her cello and the two perfectionists would incessantly tweak. Once Britell gained a foothold in the world of film composing — establishing collaborations first with producers Dede Gardner and Jeremy Kleiner, and then directors like Jenkins and Adam McKay — not only did the scope of his projects expand, his involvement did, too, allowing for more time to musically explore and experiment. For Britell, who composes on piano, having access to an ace cellist while he worked became a game-changer.

“If you play a middle C on a piano, and then you play a middle C on the cello, they’re the same note technically, but they’re totally different,” said Britell. “I’ve learned as I’m writing music, I’m lucky to be able to say, ‘Caitlin, can you play these two notes for me, please.’ And just hearing them and being like, ‘Oh, wow.’”

One of the biggest lessons Britell has learned from working with Sullivan is how to better communicate with musicians. Not unlike a director working with an actor, when a good performer understands what is needed, they can unlock a piece’s potential with their craft. Sullivan points to their “Beale Street” breakthrough as an example. “Nick had me layer on top of myself, it’s all layered multitrack cellos, so I didn’t necessarily know what the architecture of the piece was as I’m doing one at a time,” said Sullivan. “Nick is an amazing coach, he’s conducting me, and I know what he’s asking for, and then I realize as we talk he needs a little bit more of this sound, or ‘Can you do a little bit more of this?’”

Jenkins has watched how the couple has developed their own complex musical language over the years. And while he’s not in the room for that process — even when they were all working and living under the same roof for “The Underground Railroad” — he has learned to identify and feel the imprint Sullivan leaves on his films. “‘Moonlight’ and ‘Beale Street’ are small, and you’re getting a very personal sound. The quality that’s in it has everything to do with the person playing it,” said Jenkins. “If you’ve met Caitlin in person, she’s a small person, and she’s really using her whole body to play these instruments. There was one time on ‘Beale Street’ where I just kept hearing this percussive sound, and I was like, ‘Nick, what is that? We need to boost that.’ And it was the sound of Caitlin plucking the bow, that was just making this rhythm.”

One way Britell believes he’s grown as composer, in particular from working with Sullivan, is how much “it’s not just about the notes, it’s about how the notes sound and how the notes are played.” He points to the recording of the “Vice” score at Abbey Road Studios as an example. Sullivan, who was working in London on another project, visited the recording session at a moment Britell was struggling to get the uptempo “Counterpoint in C Minor” to sound right. “Caitlin was in the booth with the mix engineer and I was on the podium, and immediately she said, ‘Hey Nick, do you wanna come in the booth for a second?’ I go into the booth and she says, ‘You know, I think there’s too many strings starting to play together right at the beginning. Just cut down the section so there’s fewer people, so they can be tighter right at the top.’”

Britell returned to the podium, made the suggested adjustment, and the next recording was what ended up in the movie. ”Everyone in the booth mentioned it would be great if Caitlin could stay for the rest of the recording,” laughed Britell. It’s an example of not just the importance of how notes are played, but also how much Britell has increasingly relied on Sullivan’s insight and instincts on this front. Gardner, who considers Sullivan and Britell to be family, has seen this aspect of their collaboration grow in recent years — in particular during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the couple was often isolated together. “There’s just some extraordinary sort of experimentation that becomes possible because they share a space,” she said. To hear the results of that “Vice” session — and other excerpts from Britell and Sullivan’s collaborations — watch the video below.

Britell has learned that whenever Sullivan pokes her head into his studio in reaction to something he’s playing, it’s a sign he’s on the right track. But in a far more practical way, the biggest impact has been the composer’s exploration of the cello’s full emotional range. So much so, the couple were already looking for a cello-led score they could produce together before Gardner first started talking to Britell about an adaptation of Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey’s nonfiction bestseller, “She Said.” Gardner and Kleiner were excited by the potential of Sullivan taking on the role of co-producing the score, in addition to being its featured cellist. The composer saw the film as one with two layers: on its surface, a docudrama set in the real New York Times building, but underneath, the internal experience of the women who lived and reported the exposé that helped bring down Harvey Weinstein. Britell’s instinct was that the cello would be the perfect instrument to weave an emotional thread through the individual stories of trauma that make up “She Said,” a film that contains over 200 scenes.

The starting point wouldn’t be composition, but working with Sullivan to discover what sounds they wanted to use to build the score, a great deal of which was determined by how the cellist played her instrument. One example, Sullivan explained, had to do with how she plucked the string. “The metal string would snap against the wooden board, and it’s a very violent type of sound.” She would also use the back of her nails against the string, which “created an effect that felt like a struggle in the way we’d use in this rhythmic, pulsating way.” According to Britell, they recorded all these ideas, talked about which they liked, and “then I would take that material, that musical matter, and I would go write pieces using these sounds [and] concepts.”

While the composing would remain Britell’s sole responsibility, Sullivan would be a constant part of the process of what sounds were used. Britell explained, “It’s things like Caitlin coming in and saying, ‘You know, I love what you’re doing here, but what about that cool sound? We need more of those.’ And I would say, ‘Oh, you’re right.'”

Having never previously watched a rough cut of a movie they worked on, Sullivan now built her emotional reaction to the film into her playing. “In watching a few scenes [there was] almost [this sense of] taking fewer breaths than you would normally,” she said. “There is a holding in.” The cellist would carry that feeling into her playing, pointing out how just the slightest shift in BPM can alter the emotional feel. The result, according to Gardner, is the audience is infused with a sense of mounting dread that the journalists Kantor (played in the film by Zoe Kazan) and Twohey (Carey Mulligan) spoke of feeling as they discovered the extent of Weinstein’s abuse, while becoming increasingly concerned they may never get to tell the full story and be forced to keep it to themselves.

Happy with the results, the two musicians are even more pleased with the process. “There were so many ways in which this type of collaboration on this project worked, it would be wonderful to find other projects we could co-produce in this way, because I love having Caitlin here in the studio,” said Britell, seated on the couch in his studio next to his wife, who added, laughing, “We talk about music all day, there’s no difference.” Britell agreed, “Might as well make it a formal thing.” –Chris O’Falt

VIEW MORE INFLUENCERS PROFILES

Luca Guadagnino & Timothée Chalamet

With “Bones and All,” the director and star of “Call Me by Your Name” continue to give each other the space to be bolder, darker, and more vulnerable.

December 1, 2022 12:08 pm

Nicholas Britell & Cellist Caitlin Sullivan

“She Said” and “Succession” composer Britell says he knows he’s on the right track when Sullivan pokes her head into the couple’s home studio.

By Erik Adams

November 18, 2022 2:17 pm

James Gray & Cinematographer Darius Khondji

What’s the collaborative process behind “The Immigrant,” “Armageddon Time,” and “The Lost City of Z”? “No conversation. Just sharing paintings.”

November 10, 2022 11:00 am

Best of IndieWire

The Best Thrillers Streaming on Netflix in October, from 'Fair Play' to 'Emily the Criminal'

Christopher Nolan's Best Shots: 40 Images That Define the Director's Career

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.