Newsroom Meddling, Money Woes: How A Billionaire Owner Lost His Star Editor at the Los Angeles Times | Exclusive

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

You are reading an exclusive WrapPRO article for free. Want to level up your entertainment career? Click here for more information.

It wasn’t a coincidence that Kevin Merida did not call his boss, Los Angeles Times owner Patrick Soon-Shiong, to warn him that a resignation was coming.

He did call his top editorial deputies and prepare them. But when the 67-year-old executive editor announced on Tuesday that he was stepping down after less than three years — five months before his contract was up — it came as a surprise, according to two people informed of the timing.

The newsroom, too, was shocked.

But perhaps they should not have been. In interviews with a half-dozen individuals close to the LA Times news operation, it became clear that Merida’s relationship with Soon-Shiong — though never close — had broken down irreparably by the end of last year over the owner’s interference in newsroom decisions, a lack of support for Merida’s independence as editorial leader and ongoing financial losses with no apparent plan to reverse them.

Hillary Manning, the LA Times spokesperson, denied that Soon-Shiong interfered in newsroom decisions. “Patrick Soon-Shiong and the Soon-Shiong family have not interfered with newsroom decisions,” she said in an email to TheWrap. “You will never find anyone credible to dispute that.”

But two knowledgable individuals confirmed this was the case. In November, Soon-Shiong and his activist daughter Nika told Merida they disagreed with his decision that 20 newsroom journalists be recused from covering the Israel-Gaza war for 90 days after they signed a public statement condemning Israel. They did not demand that the recusal be rescinded, though Soon-Shiong said in an interview last week that he was “disappointed” to not be informed in advance, suggesting he might have prevented the decision at that time had he been told about it.

Soon-Shiong, a medical doctor and biotechnologist, had also disagreed with previous coverage in the health-science arena, where he conducts research, and pushed back, the individuals said. Still another incident occurred in December that involved challenging a newsroom decision that disturbed Merida, according to two individuals. “There was a disagreement over how to run the newsroom,” one of those individuals said.

Merida, who declined to be interviewed for this piece, told the LA Times last week: “I came to my decision based on a number of factors, including differences of opinion about the role of an executive editor, how journalism should be practiced and strategy going forward.” He did not give further detail.

But others aware of the tension agreed. Soon-Shiong “likes to get involved in the journalism,” said one of the knowledgeable individuals who spoke to TheWrap. “He has a lot of very strong opinions about journalists and journalism… These are not good signs.”

The individual added: “If you don’t listen to your executive editor then there’s no point for the executive editor to be there.”

“There never was a ton of trust there,” said another individual with knowledge of the relationship. “You always have to teach him (Patrick) about the stuff journalists do, ethical things, things we cover and don’t…. But Patrick wasn’t trying to learn. Unlike Jeff Bezos (billionaire owner of The Washington Post) who wanted to learn.”

For Merida, the latest incident, details of which were unclear, was the deal-breaker. He was no longer willing to live with continually having to keep his owner-boss at bay. That, combined with ongoing financial uncertainty, looming editorial cuts and the belief that Soon-Shiong’s approach to the newsroom was unlikely to change, led to a decision to leave.

But the problems at the LA Times remain.

An absentee owner

If the mild-mannered Merida was frustrated, the truth remains that the billionaire publisher has showed scant interest in running the business of the $500 million asset that he bought in 2018. He preferred, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, to spend time in his research lab and working on a vaccine.

A larger lack of structure was also a problem. Soon-Shiong’s position is “executive chairman.” But the LA Times has no publisher or CEO, no clear leader whose role is to drive a business vision for the company every day.

Instead, there is a triumvirate with Merida as executive editor, Chris Argentieri as COO and Anna Magzanyan, who is Chief of Staff to Soon-Shiong and Head of Strategy and Revenue for the LA Times, all reporting to the owner.

That leadership vacuum is key, said several who spoke to TheWrap, who note that Soon-Shiong’s true passion is science. “I don’t know that Patrick looks and says – how good are we? Are there alternate sources of revenue? Are we getting all the revenue that’s out there. What are the new ideas?” said a frustrated staffer.

Somewhat unconventionally, he and Merida had no standing meeting. The two would communicate by phone or text when an issue arose.

Furthermore, Merida was frustrated to not have a clear budget with which to run the newsroom. After the severe newsroom cuts that came mid-year in 2023 and continued financial losses, he did not have confidence in any budget figure for the newsroom.

“It’s almost like giving money as needed. You don’t have something you know you can count on — and then you’re faced with unexpected cuts,” said one insider, who said that even Argentieri referred to the system as “pay as you go.”

“It doesn’t create the kind of stability you need,” this person said.

Meanwhile, the paper has continued to lose money while failing to meet its subscriber targets, despite cutting 74 jobs from the newsroom — 13% of the edit staff — last summer.

Soon-Shiong has had to sink an estimated $300 million in additional cash over the last five years to keep the operation going. One former top editor estimated the Times was losing $50 million a year, on top of Soon-Shiong paying $500 million for the asset.

Two others interviewed by TheWrap recalled Soon-Shiong saying in meetings that he had put nearly $1 billion into the LA Times.

When Soon-Shiong made the investment, he said at the time he wanted to invest in a civic project that would support democracy and serve the community. In standing by that commitment, he spent heavily to grow the newsroom (by close to 30% in headcount), built a state-of-the-art kitchen for the Cooking section and a pricey video platform.

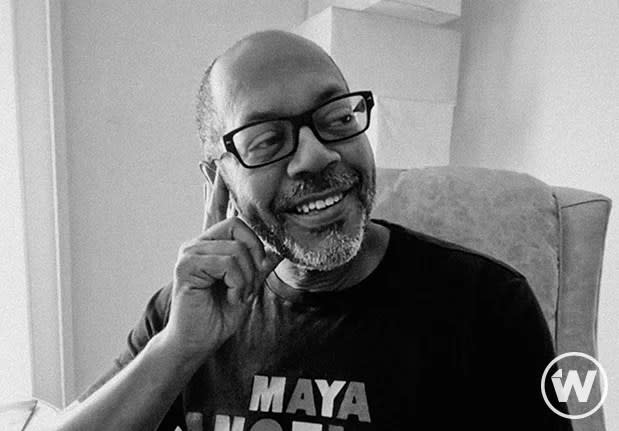

Hiring Merida was a coup. The news executive previously led The Undefeated, an award-winning ESPN news unit that explored the intersection of race, culture and sports, and served as chairman of ESPN’s editorial board. Before that Merida spent 22 years at the Washington Post, where he rose to managing editor in charge of news, features and the universal news desk. Many expected him to rise to the top of that newsroom.

But even with the arrival of Merida and three Pulitzer Prizes, including two in 2023, the revenue has not appeared.

The LA Times began, for the first time in its century-long history, to lose money. The digital advertising did not overtake print, as was necessary in a pivot to the digital age, and while paid subscriptions rose to 550,000 — a number that includes direct sales and third-party partnerships like Apple News+ — it falls far short of Soon-Shiong’s ambition.

“The LA Times does good journalism but it has not figured out how to become enough of a must-read to readers in Southern California,” said the former editor.

“The LA Times needs 1 to 1.5 million in circulation just to be viable,” this person said. “And it is stuck at around 700,000.”

The June cuts involved audience staffers, social media staffers, copy editors, photographers, videographers and some people from newsroom operations. But management consciously avoided letting go any staffers “who were actually writing stories,” as one put it.

More layoffs are widely expected in 2024.

Tension over Gaza

In November, three dozen LA Times journalists signed a statement condemning Israel’s incursion into Gaza in the wake of the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel.

The letter condemned Israel’s bombing of Gaza and demanded that newsrooms use language like “apartheid,” “ethnic cleansing” and “genocide” to refer to the Israeli military operations in the region. It has been signed by more than 1,400 current and former journalists around the world.

After conferring with his top deputies, Merida ordered that those journalists be recused from writing about the Gaza conflict for 90 days, reminding staff of the company’s ethics and fairness policy. The policy outlines that a “fair-minded reader of the Times news coverage should not be able to discern the private opinions of those who contributed to that coverage, or to infer that the organization is promoting any agenda.”

Except for some pushback, the edict was accepted in the newsroom, and there was agreement among the top editors that the response was necessary to safeguard the paper’s credibility in covering the conflict.

One newsroom insider called the decision “a no brainer.”

“Kevin’s decision was conventional,” said Paul Farhi, a veteran Washington Post journalist who covered media until retiring at the end of last year. “It just doesn’t comport with the views of a younger generation of journalists who feel they’re entitled to express their opinions.”

At The New York Times, a writer who signed the letter, Jazmine Hughes, resigned because her doing so “was a clear violation of The Times’s policy on public protest,” as her editor put it in a memo to the staff.

But Merida did not inform Soon-Shiong until after the decision was implemented. The billionaire and his daughter, Nika, both made clear they did not agree, according to two individuals. Nika Soon-Shiong, 30, is vocally anti-Israel. Her X social feed has a Palestinian flag in her bio, and a pinned tweet comparing Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with Cecil Rhodes, the racist founder of Rhodesia. (Nika Soon-Shiong did not respond to requests for comment made through LinkedIn and her charity, Fund For Guaranteed Income.)

“It’s highly unusual for the owner, or a family member, to be expressing viewpoints when or if she has some influence over the editorial direction of her family’s publication,” said Farhi. “Traditionally, ownership has taken its hands off on controversial issues. They don’t express direct opinions like this, except through the editorial board of their publication…. That’s why you hire an editor to run the newsroom.”

The Soon-Shiong family comes from South Africa, and Patrick grew up under the apartheid regime. Although he is generally described as politically centrist, his views on the Israeli-Palestine conflict did not comport with Merida’s decision regarding the activist journalists.

Ultimately, Soon-Shiong did not force Merida to reverse his decision. But clearly it was a warning sign of tensions that would continue to escalate. The 90-day recusal deadline looms in mid-February and the remaining editors will need to decide what to do next.

Farhi said it would be problematic for the Soon-Shiongs to dictate that next step: “It’s when you cross the invisible wall to the newsroom that it becomes problematic. The newsroom is supposed to be independent – even of the publisher.”

The fallout

“We mutually agreed that he perhaps was not the right fit,” Soon-Shiong told the LA Times in the article announcing Merida’s departure.

But despite all these difficulties and the embarrassment of Merida’s exit, the Soon-Shiong family reconfirmed in the LA Times that it has no intention of selling the paper.

Newsroom staffers who talked to TheWrap said that Merida’s leaving was a shock, and are worried about the newspaper’s future.

Merida “was well-liked. I liked him. Not sure he changed the game. People were shocked he was leaving,” said one staffer. “I don’t know that he ever had a well-articulated vision of who we are and what we are focusing on. People were excited when he first came. But not much has changed at the paper. We have done a lot of work but are still facing layoffs and in a tough spot.”

Few staffers had any one-on-one contact with Merida, who joined in 2021 and was initially introduced over Zoom in the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly the entire staff has been working remotely for almost three years. Owner Soon-Shiong instituted a stay-at-home order in March of 2020 and staffers still haven’t been told to go back to the newsroom. If they do, they are required to wear a mask in the building.

A possible return to the newsroom is currently part of contract negotiations, two staffers told TheWrap. The guild is still negotiating a new contract; the last one expired in 2022 after three years.

“Part of why people are upset is we don’t know what is coming next,” said one of the staffers, on condition of anonymity.

The difficulty for Soon-Shiong will be recruiting another editor of Merida’s caliber.

“It’s going to be very hard to attract” a similar candidate, said one of the insiders who spoke to TheWrap. “I would be surprised if they get an outsider. There are not a lot of people inside who even want the job.”

The post Newsroom Meddling, Money Woes: How A Billionaire Owner Lost His Star Editor at the Los Angeles Times | Exclusive appeared first on TheWrap.