‘Never Look Away’ Review: A Sketchy Three-Hour Epic About a Brilliant Painter

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 2006, a 33-year-old German director named Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck took Hollywood by storm with his Oscar-winning debut, a manipulative and wantonly middle-brow spy drama about a heartless Stasi captain’s long road to redemption. Told with a watchmaker’s precision and finished off with a tear-jerking gut punch of a finale (complete with a freeze frame for good measure), “The Lives of Others” offered a seductive peek at a shadowy part of history, and seemed to herald the arrival of a filmmaker who might be able to class up some Hollywood fare, or even sell American viewers on the idea of reading subtitles. Then von Donnersmarck made “The Tourist,” and that was the end of that.

Now, eight years since his disastrous — but Golden Globe-nominated! — dalliance with the studio system, von Donnersmarck is ready to walk his own long road to redemption (even if his most grievous crime was failing to save a Johnny Depp movie from itself). And what a long road it is: 189 minutes, to be exact, every one of them burnished with the same genteel watchability that made “The Lives of Others” such a crossover success.

More from IndieWire

An epic piece of fiction inspired by the life and work of Gerhard Richter, “Never Look Away” is a return to form in the most literal sense of the phrase, as it finds its director retreating to the same mode for which he became famous; it even finds him doubling back to the same time period, the same handsome star, and the same vague insistence that art should allow people to transfigure their personal trauma into self-ennobling peace of mind. The film is as confident and sweeping as von Donnersmarck’s breakthrough, and even more determined to explore how the psychic fallout of the Holocaust shaped the reconstruction of Germany on both sides of the Berlin Wall — it would make a fine double feature with Luca Guadagnino’s “Suspiria” for anyone willing to sacrifice an entire Sunday.

But where “The Lives of Others” was held together by a moral velocity that allowed viewers to overlook the convenience of its storytelling, “Never Look Away” is more sure of what it wants to say than of how it wants to say it.

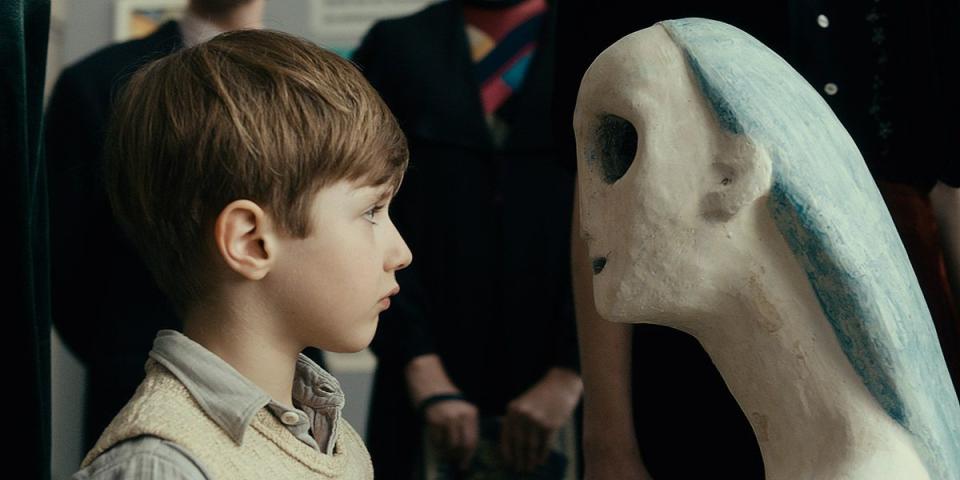

Spanning from Dresden in 1937 to Dusseldorf in 1966, the story begins when a wild-eyed young Aryan woman named Elizabeth (Saskia Rosendahl) takes her tiny nephew to see a Nazi exhibition on “Degenerate Art.” Otto Dix, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse — all the usual suspects are there, strung up on the walls of a museum as examples of obscene work that Goebbels saw as “an insult to German feeling.” For little Kurt Barnert (Cai Cohrs), barely old enough to wipe himself but already showing raw creative talent, the scene is dismaying: “Maybe I don’t want to be a painter after all,” he says to Aunt Elizabeth, squeezing her hand in his. It will take a World War, a couple of monumental coincidences, and some kooky art school friends in order for Kurt to find his way back to the wonder that was snuffed out from him that day.

His journey starts where Elizabeth’s ends, as Kurt’s creative streak is galvanized by his aunt’s emerging schizophrenia (memorably expressed in a scene where Rosendahl strips naked to play the piano, the first of several instances in which von Donnersmarck uses the female body as a window into the male brain). “Everything that’s beautiful is true,” she tells him, imbuing those words with enough grace and gravitas to fool you into a false sense of depth. “Never look away.” When the Nazis learn of Elizabeth’s condition, they mark her down for sterilization; for all of her beauty, and her avowed potential to bear strong German soldiers, she’s still regarded as a stain on the master race.

Enter the bad guy, a man whose cold and clinical disposition only underlines the extent to which he’s a cartoon monster. His name is Professor Carl Seeband (Sebastian Koch, the square-jawed hero from “The Lives of Others”), and he insists that you never leave off the “professor” part. An evil gynecologist whom the Nazis have conscripted into their eugenics program, Carl has a Marvel supervillain’s ability to sniff out physical “weakness, and no empathy to moderate that gift. It’s he who condemns Elizabeth to death, even when she begs him to think of her as his own daughter. And, some 15 years later, it’s he who scowls at the scrawny young artist making eyes at his actual daughter.

Kurt, now a wispy twentysomething played by popular German actor Tom Schilling (“A Coffee in Berlin,” “Woman in Gold”), falls in love with Ellie (“Transit” star Paula Beer, inspiring dreams of what Christian Petzold might do with this material) the moment he sees her in a classroom of their restrictive East German art school. She’s intrigued by his sensitive nature, and how his poetic soul is almost an act of defiance against the ruthless productivity of the other painters at the GDR academy. It would almost have to be that, as Kurt has little else to offer as a character; he’s haunted and withdrawn, passive whenever he’s not looking for something he can’t seem to find. “Me me me,” he often repeats as a facetious mantra, and yet there’s almost nothing to him. Schilling is powerless to break him out of that shell, and — even after more than three hours — the film’s protagonist is still an empty vessel of sorts, waiting to be filled by the symbolism of a narrative that’s more story-driven than von Donnersmarck might care to admit.

For all of the script’s talk about truth, beauty, and the value of representational expression, “Never Look Away” is always more of a soapy melodrama than anything else (a stylistic choice which, in its own way, might generously be construed as a comment on truth, beauty, and the value of representational expression). There isn’t a single moment of this movie that makes it possible to forget that you’re watching a movie. Caleb Deschanel’s saturated lighting is soaked with myth and romance, so that even the most painful moments feel like they’re embalmed in a hard coat of amber.

Read More: Asian World Film Festival Showcases 14 Foreign-Language Oscar Contenders

The script, likewise, skips from one suspenseful development to the next, tripping over all manner of hamfisted moments along the way. Kurt refers to Ellie as a “golden pheasant,” and sweeps the young woman off of her feet with lines like “You’re so beautiful it’s almost unromantic… it’s so easy to love you.” Swap Schilling out for lookalike James McAvoy, replace the German for English and the GDR with mid-century America and this sophisticated arthouse fare might as well be a very special episode of “This Is Us.”

Not that von Donnersmarck has much choice when trying to turn a profit on the kind of miniseries-length melodrama that people too seldom make anymore; “Never Look Away” needs to be entertaining to sustain itself, and the film is ultimately held together by the force of its narrative inertia. All of the developments in the plot — and all of the artistic digressions that pop up between them — are in the service of a single eventuality: At some point, Kurt is going to realize that his wife’s father is the Nazi eugenicist who sentenced his beloved aunt Elizabeth to death, and the discovery is going to reshape his existence.

Von Donnersmarck engineers enough anticipation for that moment to hold our interest as the story shifts from East to West Germany, where Kurt enrolls in a Dusseldorf art school and falls under the spell of an enigmatic professor with a tragic backstory of his own (Oliver Masucci as Antonius van Verten). The movie depends on the perpendicular desires of seeing Kurt learn the truth about his past and unlock the artistic potential of his future, and leans on those things to the point where Ellie is all but erased from the narrative — by the time all is said and done, her uterus has more of a character arc than she does.

It’s a flaw that would be easier to “forgive” if the payoff were worth it; if the film’s climactic barrage of epiphanies and breakthroughs were as satisfying as those at the end of “The Lives of Others,” but they’re not. It’s here, of all places, where “Never Look Away” shifts towards a more representational mode. In emphasizing how art allows us to make sense of the past, and consecrate even the most banal of sins, Von Donnersmarck loses his grip on the emotional payoff of the present. This is a beautiful movie, and occasionally one that rings true. But, in contradiction to aunt Elizabeth’s claim, it’s seldom both of those things at the same time.

Grade: C+

“Never Look Away” is now playing in New York and Los Angeles for a qualifying awards run. Sony Pictures Classics will release it in theaters in February 2019.

Best of IndieWire

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.