New Netflix movie 'Maestro': Leonard Bernstein also loved IU's School of Music

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct that Brahms' stool was given to Bernstein.

The 2023 film “Maestro,” directed by and starring Bradley Cooper, will chronicle the life of Leonard Bernstein. The movie focuses the composer's 27-year romance with his wife; less well-known is his love affair with the Indiana University School of Music.

“I have to report, albeit a bit reluctantly, that I have fallen in love with the school."

In January 1982, Bernstein completed his final opera, "A Quiet Place," during a nearly two-month stay in Bloomington. He came here for peace and inspiration — and because he’d heard of the musical talent IU produces.

While in Bloomington, Bernstein got to know Charles Webb, who served as the School of Music dean for 24 years. The duo developed a lasting friendship, which is featured in a 1997 IU mini documentary called "Charles Webb: Making Music."

“I have to report, albeit a bit reluctantly, that I have fallen in love with the school,” Bernstein says in a speech excerpt included in the video.

In a 2017 episode of the podcast series "Through The Gates at IU," Webb talked about what drew Bernstein to the university. The composer was suffering from writer's block. He was in a slump. He sought a major music school where he could compose at night and bring manuscripts for students to rehearse and review the next day. The IU School of Music, he decided, was the perfect fit.

"He had this kaleidoscopic knowledge," Webb said in the podcast. Students benefited from the mentorship of one of the greatest composers in the 20th century.

"When he entered a room, time stopped."

Sylvia McNair was a student at the School of Music when Bernstein arrived. She remembers Bernstein as an "incredibly sensitive soul" and a "brilliant mind," whose proclivity for partying matched his creative genius.

"In the second half of the 20th century, Bernstein was the king of the music business,” McNair said. “He redefined the role of a great American maestro.”

After her graduation from IU in the spring of 1982, McNair won two Grammy awards, performed operas internationally and returned to the recently renamed Jacobs School of Music as a faculty member from 2006-2016.

As a student, she met Bernstein after starring in the opening night of a Mozart opera. Before taking the stage, she learned the famous composer was in the audience. She steadied herself, and even today she remembers thinking, "OK, Sylvia, dig deep and pull out the best performance you can."

She must have made an impression; eight years later Bernstein invited her to perform with the New York Philharmonic. But it never happened. Bernstein passed away shortly after.

During his short stint at IU, Bernstein took up space — musically, intellectually, emotionally. He wasn't perfect, McNair said, but his presence lingered in the halls and in the hearts and minds of young musicians.

"When he entered a room, time stopped."

Bernstein, Bloomington and Webb: a lasting relationship

Bernstein's connection to the university began before — and continued long after — his stay in town.

In 1977, IU students performed “Trouble in Tahiti” in Israel at Bernstein’s request. This marked the beginning of his sponsorship of Bloomington music students. Five years later, he would head to southern Indiana to compose that opera's sequel, "A Quiet Place."

A few years after his '80s Bloomington visit, Bernstein started a scholarship fund at the School of Music. The composer won the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize, sometimes called the "Nobel Prize of music," in 1987, and he donated two-thirds of the money to IU. Chancellor Herman B Wells matched the gift. Music students have been awarded the Leonard Bernstein Scholarship every year since.

Bernstein turned 70 in 1988. To honor him, the Boston Symphony Orchestra threw him a birthday gala at the famed Tanglewood Music Center. When asked what piece of his he most wanted performed, Bernstein requested "MASS." It's a huge undertaking. Tanglewood did not have the personnel to accomplish it.

Invite IU School of Music students, Bernstein said. His confidence in them was unwavering.

IU sent a group of 250. After the performance, Bernstein took the stage and said, "This is one of the finest performances I've ever seen." The audience roared with applause, but Bernstein continued: "I don't mean only of the mass. I mean of anything."

In interviews, Bernstein attributed the success to Webb. "It's the spirit of Dean Webb," he said. "God bless him."

That same year, Bernstein released one of his final pieces. The song cycle is called "Arias and Barcarolles." In it, he made one last tribute to the dean.

In the podcast episode, Webb recalled his surprise when an envelope mailed to him revealed a handwritten score of music. It was the seventh piece of music in "Arias and Barcarolles," and it was devoted to the dean and his family. The title? "Mr. and Mrs. Webb Say Goodnight." The piece included the parents' and children's names, and has since been recorded and performed across the world.

“It was a portion of the very last piece he wrote before his death," Webb said. Bernstein died two years later, in 1990, at age 72.

The Bernstein Collection: a 2,100-item refrain

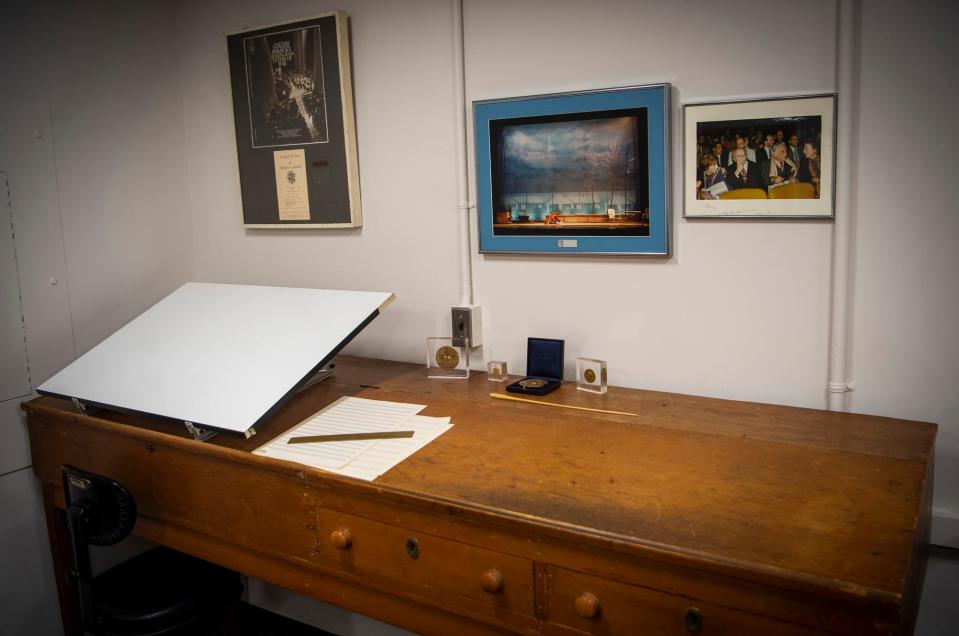

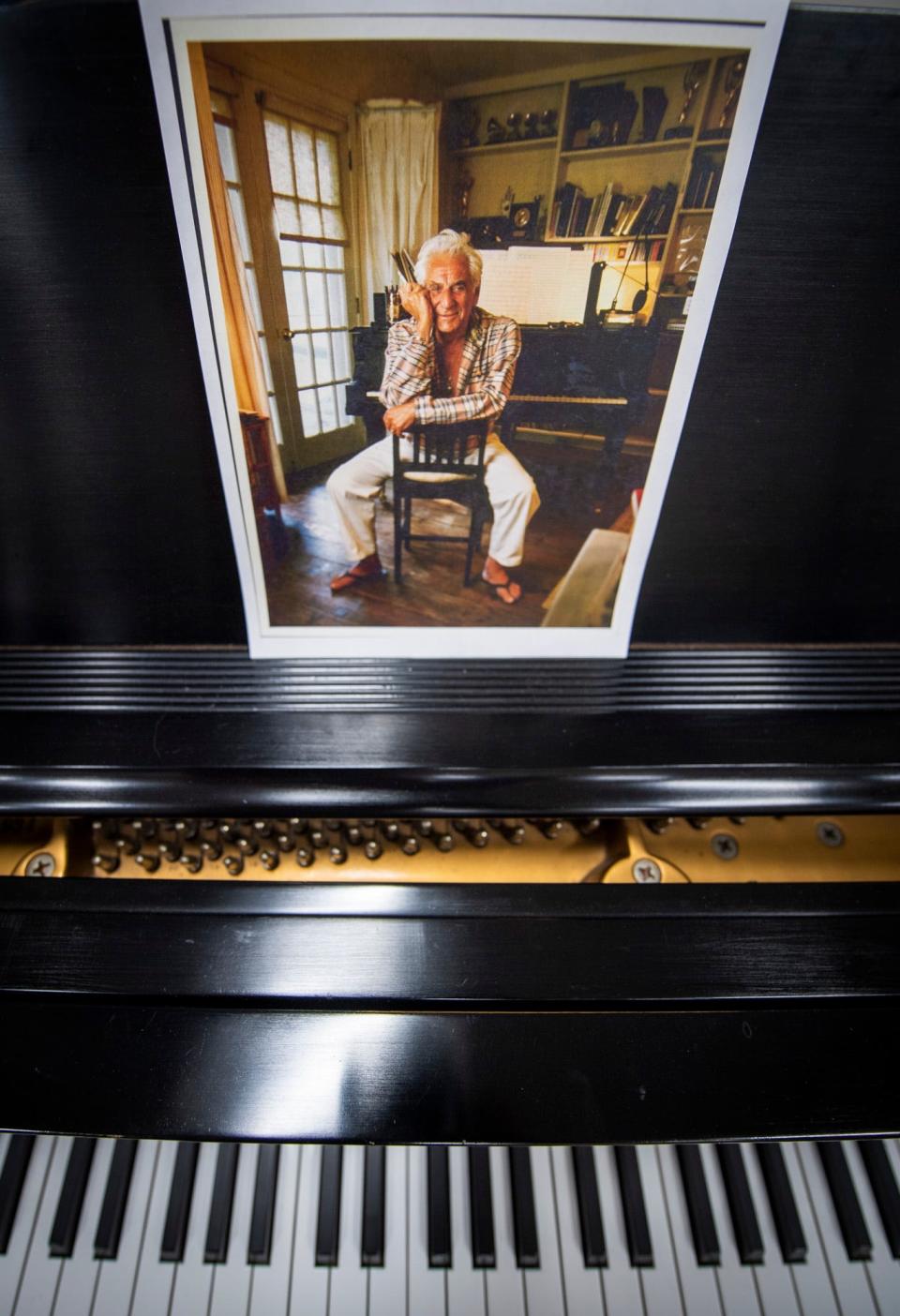

In 2009, Bernstein's three children donated a collection of 2,100 artifacts from his Connecticut composing studio. The materials, created between the 16th and 21st centuries, are now on public display in the school's Simon Music Library and Recital Center.

But only one-third of them are in the small replica of Bernstein's office, said Phil Ponella, the collection's curator and Wennerstrom-Phillips Music Library director. The rest are stored away in a music library vault.

The exhibit contains furniture: a yellow, sagging couch, the desk Bernstein used after 1962 to compose every work, even a stool that was said to have been used by Johannes Brahms. The walls are filled with framed honorary degrees and accolades. In glass cases sit Grammy awards, the age of one conveyed by the bits of fishing wire and glue holding it together.

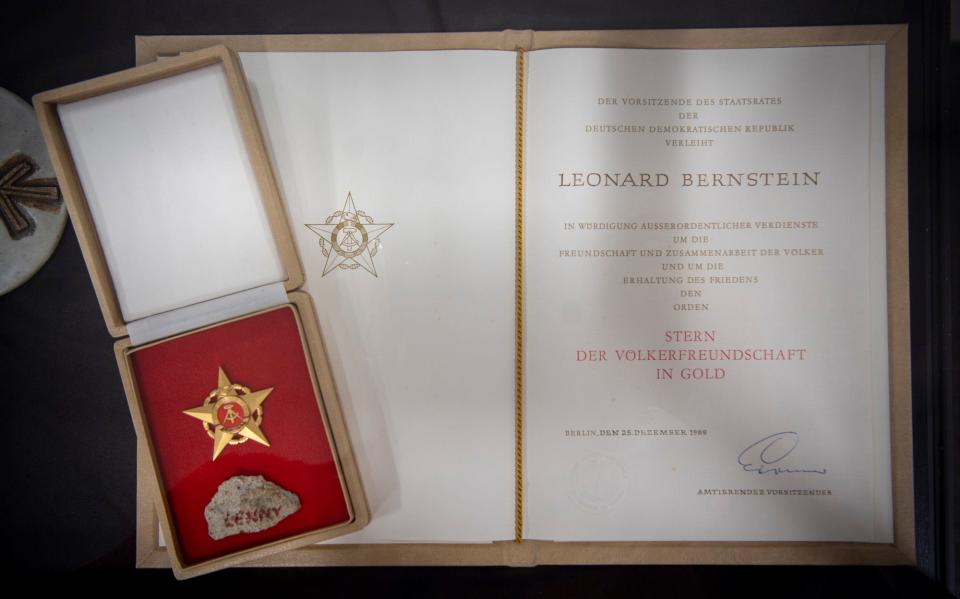

There's a walnut-size chunk of stone, too. It's a remnant of the Berlin Wall, one Bernstein himself chipped off. Scrawled on its surface in marker is Bernstein's nickname: "Lenny."

What's missing among the memorabilia are the scores he composed. Those are treasured by the New York Philharmonic and the Library of Congress, among others, Ponella said.

Though the stuff Simon Music Library has is just that — stuff — it tells stories about the man who once owned it.

Ponella chuckled as he gestured toward one table. Bernstein was a chain smoker, he said. “Always in arm’s length, he had drugstore reading glasses, Afrin nasal spray and an ash tray."

Guests can visit the collection by appointment by contacting Ponella at pponella@indiana.edu or 812-855-2170. The collection contents are also browsable on IU Archives Online.

More about the movie — and the maestro himself

“Maestro” will premiere at the Venice Film Festival this September. According to Netflix, it'll have a limited theatrical release Nov. 22 and will be available to stream on Netflix on Dec. 20. The film is produced by Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Todd Phillips, as well as Cooper, who co-wrote the screenplay with Josh Singer.

It’ll also star Maya Hawke (“Stranger Things”), Jeremy Strong (“Succession”) and Carey Mulligan ("The Great Gatsby”). Though the film tells Bernstein’s story, it focuses specifically on his relationship with his wife, Felicia Montealegre, played by Mulligan.

From 1957 to 2010, the renowned composer received seven Emmy Awards, two Tony Awards and 16 Grammy Awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award in 1985, according to the Leonard Bernstein website. Besides orchestral pieces, operas and vocal music, Bernstein wrote musicals, including “West Side Story” and “Candide.”

But it's a disservice to remember Bernstein only as a musician, IU alumna McNair said. He was a humanitarian who protested the Vietnam War, an American-born Jewish man who worked with Holocaust survivors, and a queer activist who raised funds for HIV/AIDS research.

She said his legacy at IU's School of Music is only a sliver of the influence he had upon the world.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: 2023 movie Maestro: Leonard Bernstein's connection Bloomington and IU