Netflix’s ‘The Lady of Silence’ May Be the Year’s Best True Crime Doc

You can scarcely surf the great streaming ocean without happening on a serial killer documentary or series, a fact that probably says more about us than the entertainment industry. All options, however, are not created equal. For every few quick-and-dirty procedurals, you’ll find something with real style and personality — something like The Lady of Silence: The Mataviejitas Murders, a zesty doc that walks right up to the edge of dark comedy, peers over the cliff, and takes a cheeky plunge into something weird and wonderful. Director Maria José Cuevas has located the overarching absurdity in a tragic story; in full command of her craft, she emerges as a talent well worth watching.

On the surface, The Lady of Silence is no laughing matter. From 1998 to 2006, a serial killer targeted elderly women in Mexico City, strangling them with telephone cords, rubber bands or whatever else was handy. The killer sweet-talked victims, entering their homes with offers of financial aid and help battling the bureaucracy of the social assistance system. Police tracked down suspects and even made arrests, but the killings continued. The authorities figured their suspect was a strong, stocky man capable of administering a chokehold. As we eventually learn, they had no idea.

More from Rolling Stone

The First Orthodox Jew Close to Making the NBA Gets the Doc Treatment

Sarah Paulson, Star of Many Netflix Shows, Strikes Against Netflix

'Heartstopper' Trades Stifling School Grounds for Ultimate Paris Romance in Season 2 Trailer

You know you’re in for something special from the moment of the elegantly animated title sequence, which carries more than a touch of Saul Bass. Next, you notice Enrico Chapela’s symphonic score, playful one moment, then somber, then suspenseful, always nimbly commenting on the action at hand. As it turns out, the Bass inspiration isn’t the only Hitchcockian touch here. The Master of Suspense was also a master of gallows humor, a filmmaker always quick to have fun with the darkest corners of the imagination. Hitchcock knew the worst crimes — say, a murderer who targets old ladies — sent people into a justified tizzy, and he loved to capitalize on that tizzy. So, too, does Cuevas.

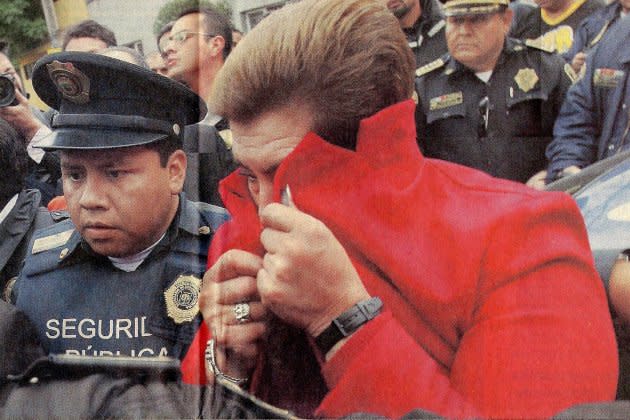

The film is infused with a relentless energy, created through a steady rhythm of resources. Maps. Extreme overhead shots. Period news footage. The Lady of Silence is speedy, but it is also laden with the kind of cultural context that turns a good story into a great one. The grandmother, we learn, is a sacred figure in Mexican culture, as exemplified by the Golden Age Mexican actress Sara Garcia, who made a career of playing grandmas. Media coverage of Juana Barraza, a former professional wrestler who came to be called La Mataviejitas (or “The Little Old Lady Killer”), played this angle to the hilt. But journalists and victims’ family members lament that Mexican law enforcement was far more interested in the killings of younger women in Ciudad Juárez than in the elderly victims in Mexico City. The Lady of Silence is as much a work of cultural criticism as a story of suspense.

A sense of mischief runs throughout, evident nowhere more than in the interview sequences. Cuevas excels at spotlighting vainglory, and there’s plenty to go around here. She films one former government official, Gabriel Regino, posing in front of a massive portrait of himself. Nicknamed The Tiger, the besuited Regino has a gaudy painting of a snarling tiger rising from water mounted behind his desk. The irony appears lost on him. A mournful friend of a victim is filmed with a cat, then a dog, then a different dog, all vying for screen space. A criminologist makes a composite bust of the suspect and stores it in her fridge, scaring the bejesus out of her family.

The lovingly executed reenactments are framed and lit with the kind of care usually associated with big-budget movies. It’s easy to imagine Errol Morris or Luis Buñuel watching The Lady of Silence and nodding in approval at the level of craft and attention to life’s strange pageant. And that’s even before the deep dive into women’s wrestling culture takes center stage.

One might argue that The Lady of Silence has way too much fun with a sad, violent story. Fair enough. But Cuevas is well aware of her film’s tragic underpinnings. She provides room for grief, yet she’s not interested in letting anyone off the hook, especially when it comes to quietly skewering those in charge. Her film walks a fine line between observing the serious and pointing out the ridiculous. She is, in short, a major talent, and she has made a film that rises above the din of its packed subgenre.

Best of Rolling Stone