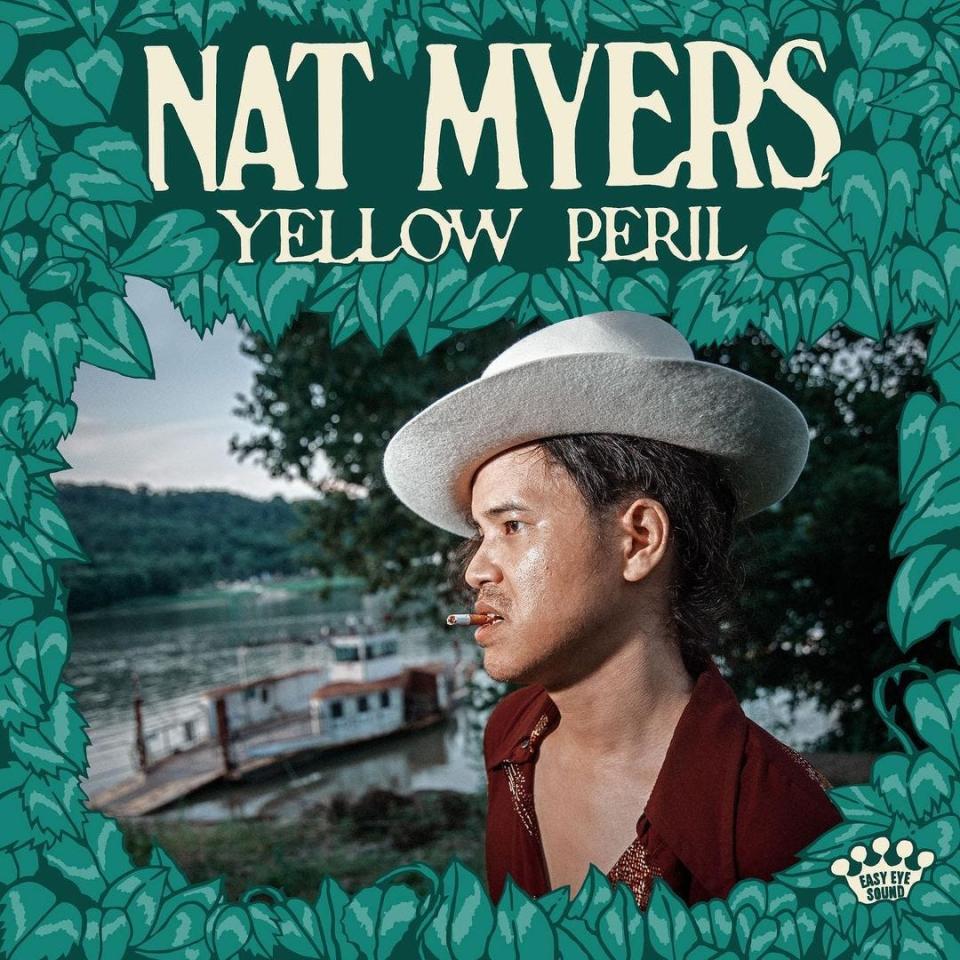

Nat Myers' 'Yellow Peril' takes a bluesy, 'oxymoronic,' anachronistic road to civil rights

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On the surface, Korean-American bluesman Nat Myers seems as out of place as fresh-made, cracklin' style pork rinds in modern downtown Nashville served with a side of Alabama white sauce. But take a step away from Concord Music's offices, listen to his forthcoming album "Yellow Peril" and walk into the Pinewood Social restaurant with a musician as inspired by hip-hop and hardcore music as he is by blues performers from a century ago like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Carl Martin and Charley Patton. They feel like the only appropriate menu item to order.

The 32-year-old artist bristles when called a "bluesman" by The Tennessean. He'd much rather be a poet.

His poetry chronicles a life lived in a "cloud of sadness and generational trauma."

Press releases for his June 23-released, 10-track, Easy Eye Sound album "Yellow Peril" chronicle how the artist's latest release handles "complex themes of identity, otherness, and determination," plus how he developed an unlikely friendship with actor Jason Momoa built from their shared passions for combatting hatred shown towards Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders.

"Yellow Peril"'s songs like "Pray For Rain" and "Ramble No More" discuss tender notions like burying a heart in a garden and letting love grow forth or being brave enough to accept that true love is more potent than wanderlust.

It's also a COVID-era album featuring a steel guitar-driven folk stomper connecting his inspiration Patton's musical advocacy for Black Southerners to Myers' desires for Asian-American civil rights.

"I woke up with my gal one day and everyone was talking about this thing happening over in China," Myers says.

"I knew this thing that eventually became [COVID-19] wasn't going to be good for anyone who looked like me."

He then angrily unleashes a stream of unprintable ethnic slurs used against him about his Asian heritage that, alongside his unique upbringing, develop an acutely human layer beneath those previously-mentioned conversations. It provides a far more compelling reason to listen to Myers' album.

The artist grew up knowing he had "15 or 16" different aunts and uncles because his Korean immigrant mother was born to a "serial philanderer." After the Korean War, she wed an American G.I. from Ft. Wayne, Indiana, who "got a bad number" and served America during the conflict.

Insofar as his "unhealthy" family life ("I was raised by two adults who had a lust for life, but were dealt a lousy hand and never entirely resolved their sadness about that"), he was raised deeply religious, has a synesthetic, piano-playing brother and spent much of his childhood and teenage years alone.

Those years were angry ones.

"I started listening to a lot of punk rock and hip-hop, plus skateboarding and getting into a lot of stuff," recalls Myers, laughing.

In an attempt to get him back on the right track, his parents signed him up for the high school band.

He destroyed his band trumpet with the same ferocity The Who's Pete Townshend saved for his electric guitars.

His mother replaced that trumpet with a left-handed starter guitar.

Pained but undaunted, he eventually studied poetry at New York's The New School, plus worked, lived and busked nationwide.

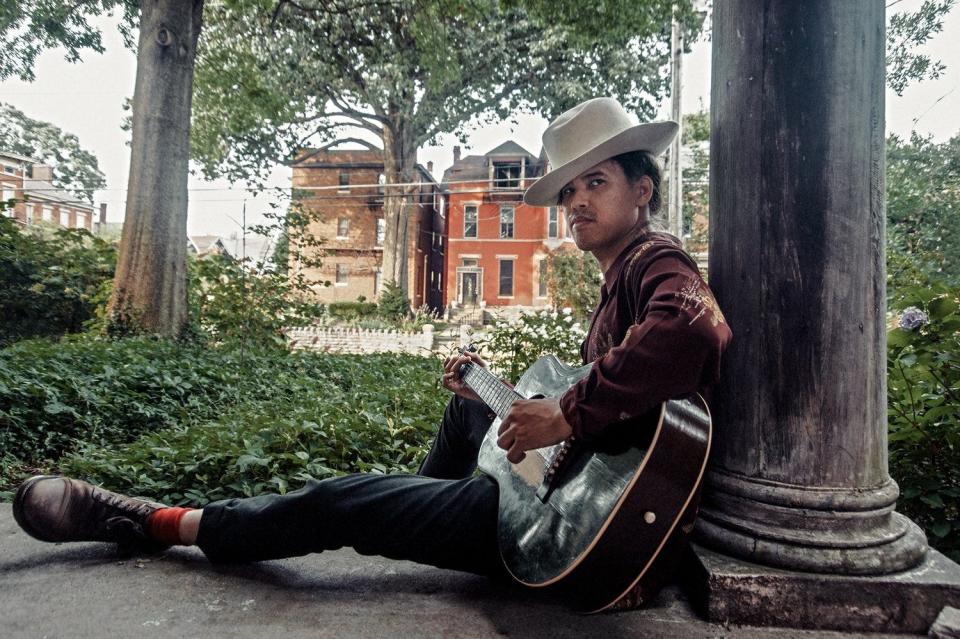

For the last decade, he's also used guitars like the one his mother gave him to create self-identity through inspirations that provide him solace in isolation.

"I don't play this music for the fans. I play this music for myself."

His defiant streak and relentless curiosity have painted him into a corner wherein his music brilliantly emanates and connects profoundly.

"I'm a young Asian cat playing old Black music," he adds, equally bemused and stunned.

Spiritually connecting with his influences has both forwarded his artistic progression and developed his existence as increasingly oxymoronic and anachronistic.

"Yellow Peril" found him "playing until their fingers bled" with Dan Auerbach in the producer's 100-year-old home. Pat McLaughlin, whose songwriting credits include 90s country to 2010s Americana-era hits for Steve Wariner, Tanya Tucker and Delbert McClinton -- plus John Prine's final hit "I Remember Everything" -- appears on the record, alongside 60-year-old Taj Mahal-cosigned Mississippi blues guitarist Alvin Youngblood Hart.

Myers' work is an ode to self-motivated but broad cultural uplifting. Impressively, the closer his modern and relevant, yet still oxymoronically anachronistic work digs deeper into the raw lineages of American popular music, his songs become demands for all Americans to achieve fundamental civil rights.

"I don't know if getting to have a little fun before we die is a viable American solution," offers Myers quoting one of his song lyrics.

He pauses and bittersweetly recalls memories of his now-deceased high school friends' wild, troubled, punk rock-listening and skateboard-riding existences.

Defining his current identity through the last time he'd achieved accurate self-definition creates a complete picture of Myers.

"I'm a s***-kicker who didn't die."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Nat Myers' 'Yellow Peril' takes a bluesy, 'oxymoronic,' anachronistic road to civil rights