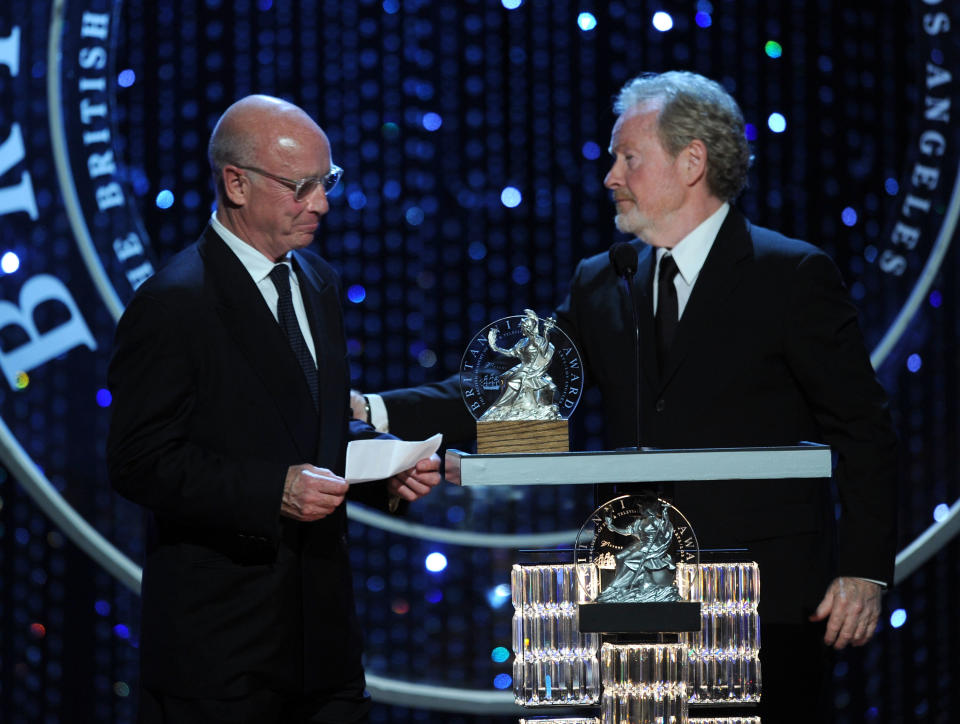

‘Napoleon’ Director Ridley Scott On Making The Epic His Hero Stanley Kubrick Could Not; Reminisces On ‘Alien’, ‘Blade Runner’, ‘Gladiator’ And When He’ll Finish That Sequel

EXCLUSIVE: Ridley Scott unveils Napoleon today at a lavish world premiere in the 2,500-seat Salle Pleyel concert hall in Paris. He is 85 but seems ageless, and Scott is already plotting to quickly resume production on Gladiator, the second installment of his film that won five Oscars including Best Picture. He’s got 90 minutes of footage, fully edited, and needs that much more. He expects to be shooting within two weeks, and he’s already got his next movie slated for around March. Though he is keeping the details to himself, he acknowledged it’s period, with a script like perfectly distilled liquor, and two stars ready to join him in what he said is a bucket list project for him.

It’s tough to keep up with Scott, the master visualist who is most comfortable making a movie, or dreaming up the next one. Interviewing Sir Ridley is a bucket list item for any journalist, because he’s so honest and playfully ornery, and because you never know what he’ll say. Like the time we spoke for The Martian. It came out around the time that JJ Abrams revived Star Wars, and after asking Scott if George Lucas’ first one made an impression, he told a now oft-repeated tale of how he saw the film in a theater with his Tristan and Isolde producer David Puttnam, and was so angry Lucas got there first that he told Puttnam he couldn’t make his film. He wanted to go to space, and that led to Alien. Scott is also quite honest about the slings and arrows accumulated along the way. Buckle up.

More from Deadline

DEADLINE: Now that the strike is finally over, how quickly can you get your Gladiator sequel back on track?

RIDLEY SCOTT: Couple weeks. Thank God it’s over. We shot about 90 minutes, at least that’s finished. It’s really getting the sets cleaned up; they’re already built. I got another 90 minutes to go.

DEADLINE: Presumably you couldn’t talk with your actors during the strike. How did you protect against the possibility your gladiators have porked up over the last half-year?

SCOTT: None of my guys do that. Paul Mescal is really very fit and stays that way. I haven’t seen the other ones yet, so I hope they’re not porked up.

DEADLINE: I have heard Denzel Washington has been working out hard. You had him in a badass turn in American Gangster….

SCOTT: That is his thing. I think it’s his manner, and obviously he’s actually in a bad mood. I think it’s just the way he is. He tends to be abrupt. You got to get used to that. But nevertheless, he’s quite charming

DEADLINE: You don’t seem comfortable at sitting around. What did you do the last half year?

SCOTT: I prepped the film after Gladiator. I have a script finished to the extent that we’ve already pitched to studios and I’ve already recce’d it. I used time out to find out where I’m going to do it.

DEADLINE: You’ve told me 2001: A Space Odyssey was a big influence on your film Alien. Kubrick finished that movie and spent two years trying to make a Napoleon movie. He eventually dropped it for A Clockwork Orange. How did you pull it off when he could not?

SCOTT: Mine has nothing to do with Stanley. I’ve always admired the French way of life. And from my very first trip down when I was 18 years old with three other buddies, we drove down in this ramshackle car and found a village with rattling chicane and fishing cottages. It was called St. Tropez, about 20 years before Bridget Bardot. I lay in the sun, enjoying the best French food I could afford, which was steak frites and dodgy wine. I lay on the beach and slathered myself with olive oil, roasting myself, and I had the worst sunburn I’ve ever had in my life. So I’ve never forgotten the French summers. And as I developed into being a successful commercial director, I loved Paris so much that I had an office there. I got deeper and deeper into the French history and their national awareness of who and what they are. My first film was about Napoleon Bonaparte, even though he wasn’t in it. That was The Duellists. It won a prize at Cannes, and from that was the kickstart to my career. That always stayed with me. I was in a place called a beautiful area, in France, the Dordogne. Years later, I did The Last Duel there, shooting less than five kilometers from where I did my first movie. In that time, I thought, let me do the greatest Frenchmen in history called Napoleon Bonaparte.

DEADLINE: Your Napoleon, Joaquin Phoenix, was quoted likening Napoleon to Hitler and Stalin. Napoleon spilled a lot of blood on the battlefield, but there isn’t a record of genocide. Do you agree with his assessment?

SCOTT: I think I compared him, and it was a quote taken out of context about who one would compare Napoleon to over history. I started with Charlemagne, and Alexander the Great, and Marcus Aurelius. Marcus Aurelius became very philosophical in his later years because I think as a human being, it probably came from guilt from the devastation he’d created around Europe to take it over and make the Roman Empire what it was. If you don’t think there was mass killing, you’re naive. So any great leader is going to be involved in killing.

There are 400 books on Napoleon. People say, which book do you read? I said, are you kidding? I as a child looked at pictures. When you look at [Jacques-Louis] David, some of the paintings done of Napoleon at the time. David was like taking a plate photograph nine feet tall of Napoleon and Josephine as they were ordained, you look at that in the cathedral, you see the audience and you can get a history lesson from the painting, right there.

So the 400 books are reports on report, on report. When probably only the original made sense, maybe written 15 years after Napoleon’s death. The next book, say 10 years later, already is writing on the first book probably is being critical, therefore is adjusting and romancing the stone a little bit. So by the time you get to the 399th book, you’ve got quite a lot of inaccuracy.

DEADLINE: Joaquin played your villain in Gladiator, and then he went on to win an Oscar playing Joker. What made you see him as your Napoleon?

SCOTT: I’m going to correct you. I saw him as the most sympathetic character of all, in Gladiator. He was a product of neglect, total neglect of a father that he adored. Then finally in the film, the father would say, I’m going to neglect you even further. You will not be the prince of Rome. And then the father realizes in his old age that he needs some form of absolute. So he does something fatal. He kneels before the boy asking for forgiveness. That was fatal because the boy has never seen his father ask for that kind of close discussion. So he suffocates him. So from that moment on, I thought Joaquin was the most sympathetic person during the movie. What he did and what followed, what came out of it, the nature of it had been created by his father.

DEADLINE: I’m going to have to watch that movie again…

SCOTT: You f*cking well better. Marcus Aurelius could not have taken Europe through a benevolence. It’s going to be war and steel, and many deaths and devastation. You can’t control commanders who are over the hill and far away, and say, do not slaughter these women and kids. None of what happened was benevolent, right? But I think with age Marcus Aurelius felt his own fragility. Commodus was the neglected son, the product of complete neglect. And then to be told, you can’t follow me, and here is who will take my place? That is more than a slap in the head. It’s terrible. And in those days, particularly when succession was so righteous and expected…

DEADLINE: You’re saying that at the end of that movie, both dead bodies in the sand of the arena were victims?

SCOTT: Yes. Maximus and Commodus. Don’t forget, Maximus is the person who didn’t want it. He wanted to go home. Interesting how things evolve when Marcus Aurelius first meets him, he said, I want you to be ticked, take over, or to be the prince of Rome, surrogate principal Rome. I can’t do that. Why not? Because my home, my wife, our kid. Tell me about your home. So then he start telling him about it, and what he’s actually talking about is heaven. That’s where he wants to be. And so it all worked backwards and some of it wasn’t planned. Marcus says, it sounds like a place worth fighting for.

And then Marcus is that day assassinated by his son. Then Russell’s character is suddenly told that this has happened and he’s not going to join the club and he knows there’s a problem. His wife and son are then slaughtered and we see where they’re in that avenue of trees where they are coming up to get rid of them. When Russell dies and goes to heaven, we go see the same woman and child; it’s the place he described to Marcus.

DEADLINE: With that indelible image of the hand of Maximus, gently touching the field of wheat. How did you come upon that?

SCOTT: Honestly, no. I shot that hand it was the last shot of principal photography. Russell didn’t come to Italy, it was his double. The guy was standing there in this field, smoking. I go, get out of the field, are you joking? It was mid-summer, dry. He says, “Oh, sorry man.” He walked out [off the field], and did that thing with the hand. I said, “Stop right there. Get the Steadicam.”

DEADLINE: You’re saying that you were trying to keep Russell’s double from lighting the dry wheat field on fire, and stumbled into that image that is one of the most memorable in Gladiator?

SCOTT: We followed the hand, no kidding. It became the catalyst for immortality, or heaven if you like, right there. It was discovered the last day, spontaneously. I consider spontaneity to be essential to what I do, you’ve always got to be watching. That’s not on paper. And so suddenly that becomes the editing room and then the theme happens. The theme is magic, and the hand is magic. Russell didn’t come to Italy, that’s his double. He said, you’ll never use that. I said, I will. When he saw the scene, he groaned. I said, too late, It’s shot. I got it, mate. It was, put out that cigarette and get the Steadicam. And don’t walk on the wheat.

DEADLINE: Your movies often get sequels, some you’ve directed and some not. What here interested you enough to direct Gladiator 2?

SCOTT: Well, economically, it makes sense. That always begins there. I thought the [first] film was, as it were, completely satisfactory, creatively complete, so why muck with it, right? But these cycles keeps going on and on and on, they repeat globally for the last 20 years. It started to spell itself out as an obvious thing to do, and that’s how it evolved. The hardest thing is getting the footprint right with the writer. There was a very obvious way to go, which was who’s the survivor? Well, the survivor could be Connie, Marcus’ daughter, but what’s even more interesting, and therefore a double whammy, there’s the son. Whatever happened to him? It became about that, and that’s Paul Mescal. It’s 20 years on. That was harder than casting Russell as Maximus, that was more obvious.

DEADLINE: Once you see Russell play that cop in L.A. Confidential, you could see he had the charisma and authority to play Maximus. What about Paul Mescal?

SCOTT: I’m always looking for someone, something new and fresh. I mean, fresh is terribly important. So they’re not carrying … baggage is a terrible word for what they’ve done before, because it’s great stuff, but you will remember he just did this character already. I watched this show called Normal People. It’s unusual for me, but I saw one and thought, that’s interesting. These actors are really good I watched the whole goddamn show and thought, damn. So this came up at a time when I need a 23 year old, 24 year old to take up the mantle of Lucius. And I just said, you want to do it? He said, yeah. He was about to do Streetcar Named Desire in London.

DEADLINE: What about Denzel?

SCOTT: There’s a parallel character, the owner of a business that supplied weapons for the Romans, who supplied the oil when they traveled, who supplied the wine they drink. They wouldn’t drink water, they drank wine. When they traveled, who would supply wagons and horses and tack? There had to be the arms dealers of the period; here is a man who already rich from supplying the weapons, the catapults. His hobby is like a racing stable except it’s gladiators. He’s got a stable of 30 or 40 gladiators. He likes to actually see them fight and it evolves that that’s where he came from. He was captured in North Africa, and evolved into a free man because he was a good gladiator. But he hides that because also he’s now realizing the potential of his actual power. He’s wealthier than most senators, so already has thoughts and designs of the possible idea of taking power from these two crazy princes.

DEADLINE: Back to Napoleon. Why Joaquin?

SCOTT: I’m thinking, who can Napoleon be? Joaquin looks like Napoleon. I didn’t say that to him, I didn’t want to make him feel too important. I was blown away by his outrageous performance as Joker. I didn’t like the way the film condoned violence, celebrated violence. I didn’t like that. But he was remarkable, and the fact he’d done that already made him a very good asset to sell the film. Napoleon, I’m also thinking commercial. It could only have been two people and I won’t mention the other actor because they may get pissed off.

DEADLINE: You’ve got incredible battle scenes, especially the ones in Leningrad where you see cannonballs plunging through the ice and soldiers falling through and drowning. You’ve got all the costumed decadence of the French upper class as Napoleon rises from nothing to the country’s leader. How long did all this take?

SCOTT: I shot it in 62 days. Normally it would take you 110, but I discovered in recent years, or actually two years ago, that two cameras are twice as fast, four cameras are four and six and eight cameras are eight times faster. So you’re scheduling a scene for the day, and I’ll be finished at 11 o’clock.

DEADLINE: The biggest challenge to working that quickly?

SCOTT: Every department has to keep up with the speed that I work. Actors do not want to hear the story of life before each take, and they do not want to actually do nine takes. I got that early on. One major actor, I won’t say who, but it was the biggest compliment, he said, boy, I love what you do because you move so quickly. He said, I love two takes.

DEADLINE: Many directors would fear they haven’t got the shot, and they repeat over and over…

SCOTT: Well, 39 takes is ridiculous. That hand in hand with using many cameras. You have to know what you are going to do next, and know the geometry of the scene. You’ve got to walk in the morning knowing exactly what you’re going to do so you can position your cameras accordingly. If you don’t, it’ll be 3 o’clock before your first shot. That’s not a good idea.

DEADLINE: You’ve gone back and made directors cuts from films like Blade Runner and Kingdom of Heaven and most say your vision is the best one. In your deal with Apple, you will put out a long version of Napoleon. Most directors will do it once, at usually longer length.

SCOTT: It felt like it saves you a lot of turmoil to say, all right, here’s the one that we’re going to put out in the theaters, but eventually I want to show you my whole vision of Napoleon. Something else comes in to that equation, which I put under the heading of the bum ache factor. How long can you sit in a theater beyond two and a half hours, before you start to get uncomfortable? Three and a half or four hours? It has to be awfully good for you to tolerate three and a half hours. Inevitably the large part of the audience are not going to go for that. And that will get around. So you’ll pay the price, when your movie peters out more quickly. You can sit there for two hours and 23 minutes. I’m not meant to talk about the long version here, but I’ll just say you come across when you’re cutting. Your first assemblage is 4 hours, 15 minutes. Can I get stuff out of that easy? You take out story, scenes, and so here, once this goes out in the cinema … there’s be moments where you bend. It’s great the platforms can show the long version. Kingdom of Heaven, I removed 17 minutes and shouldn’t have, which was the dilemma of the Princess of Jerusalem who discovered her son had leprosy. So that took that whole story sideways, and ate up 17 minutes of the movie. But to me, it just made the movie more meaty. And I removed it to get the story flying, and I regret it. But now I watch it and I think, wow, that’s good. Pretty good.

DEADLINE: Theatrical release, big budget, and then your long cut on Apple TV+. Is this how streaming logically fits into moviemaking for artists like yourself?

SCOTT: Well, I think the fact that it’s going to be seen at some point is wonderful, full stop. It’s a visual book, and people watch this visual book every night. And of course the design of the business plan of platforms saying we don’t want cinema, we will bypass DVDs, and all we want is to eat it all up on the TV, that was a bad plan. Thank God it dawned on them, my God, I’m selling out for everything I’ve done for X number of dollars a month. It doesn’t work. I do need the cinema, and there’s been a move back to that. And one of the reasons how this got the way it is on big release on cinema, I think I’ve got 400 Imax and about seven and a half thousand screen is because they realize they better screen it that way with this kind of movie. Then you can always stream later. It’s a perfect double whammy for the business, for their business. It’s better than isolating your movie only to streaming. That never made sense.

DEADLINE: That was proved out by that Barbenheimer weekend, when there was room for both Oppenheimer and Barbie, two movies that were different except each was so well executed…

SCOTT: Thank God they were. The box office was shaken with Top Gun and Avatar. Jim Cameron takes 13 years on Avatar, but it does $2.8 billion, a good deal. Top Gun: Maverick was $1.2 billion on screens, but that could have gone sideways also with streaming, until Tom said, I’m not going to do any support, no publicity unless it’s on screens. There’s no way that gross could ever have ever been equalized on the push button thing. They claim they don’t know. Of course they know. Every time anyone press a button. They know. They also know when you switch off. So we had Barbie, which felt more like a musical, and what’s good about Chris’ film is he takes such a grave subject and does it in an epic way, and he hopes for return. He got the return.

DEADLINE: He projected Robert Oppenheimer as a real Prometheus. With the best of intentions he oversaw the A-bomb, to stop the Nazi scourge because they were building one. By the time it was ready, the Nazis were in the rearview mirror and the Japanese were dug in and not giving up, and it became the most expedient way of ending the war. But it could have ended the world too.

SCOTT: Well, we’re not there yet but you’ve got a lot of atomic devices hanging around, which is very scary. And who is going to be stupid enough to press the button?

DEADLINE: The evolution of Napoleon is fascinating. Starts out this ruffian with superior war skills who becomes savior to France. But when his obsession with conquering Russia to find peace fails, the French make him a pariah. Why didn’t Napoleon succeed there?

SCOTT: He misjudged. Hitler should have crossed the channel when he was there, and bizarrely he didn’t. I’ve heard that Hitler didn’t cross the channel because he was very much guided by a spiritual entity. A person who was fundamentally stupid, said, don’t cross water in September. Napoleon went for Russia bizarrely way too late in the year and it deteriorated into a disaster. For Hitler to make the same mistake as Napoleon seemed to be crazy because Napoleon went out there allowing herself time to return. But he stayed there too long, and in that extra six weeks, midsummer just disappears. When you start the journey back to 2000 mile on foot and you start late, you’re going to meet the Russian winter, and it will kill your ass. And he misjudged it terribly. But taking Russia was personal, an ego trip. I can do anything. He knew what the Russian winter could do, but he didn’t want to face it. Now that becomes the danger for somebody like that. He can attain anything, just by his will.

When he was in Moscow, they were there quite awhile and then one evening he saw it starting to burn, and he could not believe the Russians would burn their own capital. To him, it was the ultimate act of courage and ferocity. You’re going to have nothing but scorched earth, and you’re going to die on the way out because you’ve left too late. On the way out, farms were burned, no livestock, and it’s autumn and you’ve got no supplies, nothing. They were constantly hit by Russians and Cossacks who could live off the land. They’d eat a wolf, they’d eat each other. He took out 600,000 men. I think they returned with 40,000. That is a massive, massive loss. That Russian trip was a fucking disaster. So he had to be taken away and sent away. They want to get rid of him, but put him in exile but there were too many people in quiet support of him though many were against him. Politics don’t change. It’s kind of like America, right now.

DEADLINE: What do you mean?

SCOTT: I don’t want to get into politics, I’ve got to be careful, but you have this man there who’s in an illusion of his invincibility. I don’t want to go deeper into that then that, but he thinks he’s invincible. Hopefully, he’s not.

DEADLINE: Josephine was his obsession, he craved her as much as taking ground in Europe. Then he more or less exiles her because she can’t provide an heir for him? Once she was gone, it was like he’d lost his North star. Would he have escalated his campaign in Russia if she was still in his life? She was his Maximus in heaven end, but he went too far and failed. For Josephine, there was safety and some power, being at Napoleon’s side. Did she love him?

SCOTT: I think she was always becoming an influence on him, I think. Did she love him initially? I don’t think so. By the time they came to the idea, you cannot give me a successor, I have to divorce you…that was kind of tragic. She thinks she’s going to be cast out and she’s not. She walks away with an estate, two million francs, and I’ll visit you went I can. She could not see other men. She did anyway, that’s why I had the young Russian prince go in and say, you cannot hide yourself away just because he’s no longer with you. The Russian prince was a young, handsome guy who actually was later called the Wolf of Siberia, he evolved as being really ruthless and really brutal. Napoleon knew about them, but I can’t believe it would be that personal to the point where he needed to take Russia because the prince may have been bonking. his wife.

DEADLINE: But it’s clear those photographs of her and the Russian prince drove Napoleon crazy and the chemistry between Joaquin and Vanessa Kirby is palpable.

SCOTT: You can feel it.

DEADLINE: You make us understand how Napoleon, this guy who was just kind of a thug and a ruffian, would gravitate towards a woman who’d grown up well above his station but lost her wealth and her husband and did what she had to to survive. If she could smooth out this man’s ruffian ways, she could be back in high society.

SCOTT: I’m not sure she was that invested in him more that he was invested in her, and that she saw it as a way of her living off his newfound wealth. How long could that last? It could lasted for as long as she was entertaining, put it that way. Was she good in the bedroom? Of course. Would he have ever experienced anything like that? Not at all. She was a very smart woman. I think she was particularly beautiful, but very imposing, physically imposing and powerful. And I think by the time he had become an emperor and she therefore was empress, she had to have adjusted in terms of at least admiration. Is that next to fondness? Is that next to the possibility of love? I think it got to possibility of love, and then he said, we cannot continue, I need a successor. Are you going to give me a child? She said, I cannot, because she’d had years of abortions that were done with sulfur and arsenic, so there’s nothing left.

DEADLINE: Sulfur and arsenic?

SCOTT: Oh yeah. The abortion kit would be sulfur and arsenic. There was no real contraception. So women then would adopt methods invented by doctors as to abort. Can you imagine how scary that was?

DEADLINE: We’ve spoken about the hardships of shooting some of your earlier movies, like having your actor in the Alien costume lug around this headpiece that weighed more than 5 pounds. Will this continued push into AI make that unnecessary. Many look at AI as a threat though. How do you see it?

SCOTT: You’re talking about artificial intelligence as opposed to digital. On artificial intelligence, I hit on two very important AI characters in Alien. There was Ash; having a robot on the ship in the form of a human being was genius. Suddenly there was the shock of that, on top of the alien shock. The alien was shocking, but just as you get used to the alien, oh my God, there’s a fucking robot then. AI, you can defeat the greatest chess master in 25 moves, because you can input every move ever recorded, into a computer. It will take four minutes and then it will be ready to beat your ass, beat a chess master in 425 moves, mainly because you can input every move ever recorded into a computer. It’ll decipher that in four minutes and then be ready to beat your ass. But what a computer hasn’t got is emotion. And will that be the difference? In Blade Runner, we had a computer, Roy Batty [played by Rutger Hauer] that had emotion. That’s why he was angry; he was only given four years. Right? Now, I can’t claim that was unique and enrich because Stanley Kubrick had Hal and Hal went, oh my God … to make a machine more important than the crew is fantastic. That’s where we’re going right now. So Stanley was 40 years ahead of his game. Mine were emulations of that, and not original. We wouldn’t have thought about that if it hadn’t been for Stanley, I don’t think.

DEADLINE: Between the way you used AI and the stories James Cameron told with the Terminator films, these are cautionary tales. Is AI something to be feared?

SCOTT: Completely. Who’s in charge of the AI and how smart is the person who’s in charge of the AI when he thinks he’s controlling something he’s not. And the moment you create an AI that’s smarter than you are, you’ll never know until the AI decides to do its own thing, then you’re out of control. If I had an AI box I could say, I want you to figure out how to turn off all the electricity in London. Bam. Everything was dead. That’s a f*cking time … no, it’s a hydrogen bomb. The world would close down if I switch it off, and we are all completely f*cked. We’re back to candles and matches. Do you have candles and matches at home? I live in France, so I do.

DEADLINE: Sounds like you’ve thought this through.

SCOTT: You know I’m a dramatist, so I can’t help myself. I think that is what’s amazing about Kubrick, he was good at choosing an impossible situation, and the equation around it gradually settled into what it has to be. It’s not necessarily really happy. 2001 wasn’t a happy ending. I talked to Stanley twice. First time, I’d just done Alien, and the office says, Stanley Kubrick is calling. I said, holy f*ck. He says, hi there. Listen, I just watched your movie. I need to ask you a question and I’ll get straight to it. How do you get that thing coming out of his goddamn chest? He said, it scared the sh*t out of me. That was the first exchange. I said, well, what I did, put him under the table very impractical, made an artificial fiberglass chest, screwed the table, put a T-shirt on, raised bit so it would break. He said, I got you. I got you. I got you. Next time, I’d just finished Blade Runner. And the film is essentially a film noir. He walks out, you’re going to walk away with his love, and on the floor. And there’s this origami unicorn. He picks it up and nods. This is a confirmation that he may be a replicant. He goes into the elevator and boom, finished. They f*cking hated it.

They say, you can’t do this. We’ve got to preview it again with a happy ending. I said, why a happy ending? They said, driving into mountains or something. I go, what are you talking about? Why would you live in a city if there was a mountain range just around the corner? You go live in the fucking mountains. They say, we need a preview with a happy ending. I called Stanley, I said, Hey, I know you’ve just done The Shining last year, and I know you hate flying. You must have six weeks of helicopter footage in those mountains. Can you let me borrow? So I’ve got 70 hours of footage the next day, and that footage went into the movie. That was Stanley, that was his material.

DEADLINE: Stephen King didn’t love what Kubrick did to his book The Shining…

SCOTT: Well, I honestly have to say I thought the book was better. Stanley somehow mucked around with the house, the place and the light, and the book was, I think King’s best book.

DEADLINE: You mentioned the gladiator’s hand through the wheat field. There are so many indelible images in that from, from the boy on the big wheel going over the carpet and wood floor, the bloody elevator, the twin girls murdered by their father. The author once told me Kubrick would call him at all hours, asking questions like, did he believe in God? Did he believe in evil? You can only imagine how Kubrick’s brain worked.

SCOTT: King’s book had a much darker and gloomy hotel. The Boiler Room is a monster in the book. All boiler rooms are scary as sh*t. Stanley chose deliberately to go very bright, very modern. And I thought, why? So immediately, it didn’t work for me. It made it an uphill battle on what was a very scary book. He didn’t really want to get into the shining, where Scatman Crothers says, you shine boy. He didn’t really use that enough.

DEADLINE: That was a thankless role Scatman Crothers had, driving all the way to the Overlook in a blizzard to take Jack Nicholson’s axe to the chest…

SCOTT: Some great stuff, too. I cast Tyrell in Blade Runner, from the bartender in the ballroom scene [Joe Turkel], the one he talks to there in the bar. He worked with Stanley four or five times.

DEADLINE: Ever figure out why Alien so haunted Kubrick?

SCOTT: Well, I think part of it is he didn’t make movies like I would do, and vice versa. I’d always admired Stanley, from when I was a designer. I was a designer and after Royal College I got a job drawing storyboards. I remember sneaking out at 2 o’clock one Friday afternoon because 2001 was on just down the road, in 70mm. So I went in there with my packet of cigarettes because you could smoke in those days, and sat through 2001. The theater was empty. But I walked away mesmerized feeling, this is the threshold of real science fiction and, in essence, science fact. But also it felt real because he’d been working with some guys who had been associated with NASA. So he was in a race with NASA, concerned that NASA was going to beat him to the moon before he finished the movie.

The sets were spectacular. And the most memorable thing about the thing for me was the first time it was a mention of something called a computer, and AI, and that this computer was more important than the crew. I just thought that was incredibly perverse, marvelous idea. That felt logical. So we jumped in later with Alien, and Ash became the humanized version of the box. We stole the idea in that sense, with great respect to Stanley, that Ash was more valuable than the crew.

We’d almost worn out the creature, this marvelous beast that H.R. Giger gave me. You don’t want to overuse that. It’s a bit like being prudent, and don’t show the shark too often. So I was kind of saving Ash for that perfect moment in the story where there’s a fight and he gets his head knocked off, and holy moly, he’s a robot. I think Stanley was enamored by something about Alien, that it feels real and logical that a mining vehicle coming in from outer space carrying God knows how many dollars of natural phenomena. It’s actually what we’re going to do today. First guy on Mars is going to be worth a fortune, right?

DEADLINE: Had Kubrick seen his HAL in your Ash character?

SCOTT: Only when I told him. You get two filmmakers together, they just open up and there’s nothing pretentious in there whatsoever. That continued when I had the Blade Runner issue and they wanted a happy ending, and Stanley gave me The Shining footage.

DEADLINE: They didn’t ask you back for the Alien sequel, which James Cameron directed. It’s very different, more of a roller-coaster ride.

SCOTT: Well, Jim is about that, the way he designs, his whole process is The Ride. As I learned somebody else was doing this, I actually had been trying to develop something. When Jim called me up and said, listen … he was very nice but he said, this is tough, your beast is so unique. It’s hard to make him as frightening again, now familiar ground. So he said, I’m going in a more action, army kind of way. I said, okay. And that’s the first time I actually thought, welcome to Hollywood.

DEADLINE: What was it like to learn about a sequel to your movie when your replacement calls you?

SCOTT: Jim and I talk often. We’re not exactly friends, but we do talk and he’s a great guy.

DEADLINE: How did you feel after you hung up that time?

SCOTT: I was pissed. I wouldn’t tell that to Jim, but I think I was hurt. I knew I’d done something very special, a one-off really. I was hurt, deeply hurt, actually because at that moment, I think I was damaged goods because I was trying to recover from Blade Runner. Which I thought I really got something pretty special, and then the previews were a disaster. And [my cut of] the film lay on a shelf for almost, I think 10 to 12 years after that until it was discovered by accident at a Santa Monica Film Festival. Somebody said, let’s dig out the old print and run it for fun. And they called Warners. And with the greatest respect to Warners, they’d lost the f*cking negative, which is like, what? And somebody panicked and went into a drawer, yanked up the first can that had Blade Runner on it, never checked it, sent it to Santa Monica.

They ran it. It was a cutting copy with partly Jerry Goldsmith on it, and partly my great musician on it. And it was a copy where we were getting reached to the end of the short strokes and trying to cut and recut to, as it were, save the movie. And this version had no voice-over and had what I call the film noir ending, which is Deckard stares at the origami in his hand, which is a unicorn, nods his head as if to agree and he goes off with his gal. So that got rediscovered. It came right out like a cannon shot, and went everywhere. And of course I know it. I knew it then that it was a very special form of science fiction. It hadn’t really been done like that ever and became a kind of copycat benchmark for most of the TV shows and science fictions. I mean, I got the social order of dystopian society really well, and I think that had never been done before. Now it’s copied again and again.

DEADLINE: But at the time Cameron called you, that’s enough to rattle the confidence of anyone. How did you get yours back?

SCOTT: Did a lot of pushups, play tennis, thrash the sh*t out of a tennis ball and look at the next movie. And I was already prepping Legend with Tom Cruise, Tim Curry playing the Lord of Darkness, and Mia Sara, who only did a couple of movies and decided no more. What I decided to do was something that ironically Disney hadn’t done at that point. And I always thought, why not do a live action kind of cartoon, kind of fairy story, which they didn’t go for. And of course, they do it now again and again, 25 years later. But in those days, I made it literally as the fairy story, with very little help from any digital work. I had to build the forest and the makeup on the fairies had to be real made up, makeup applied on the day. It’s remarkable. Tim Curry playing the demon … it was a success for me, just great.

DEADLINE: Now you’re not so easily wounded, but you just did a lengthy profile in the New Yorker. You had some historian knocking the veracity of your Napoleon trailer on TikTok, and you more or less said, you have the right to tell your Napoleon story and take the narrative license, as long as the audience goes along with you. I saw the movie, and wasn’t sure what the complaints were, beyond historical nitpicking. You had the good grace not to dress Napoleon in spandex and give him the power to fly, which perhaps is what people want in this digital age. Does the digital micromanagement trouble you?

SCOTT: You’ve got three questions. I think we are partly responsible for the, how do I call it, the frustration of the younger generation that goes hand in hand with the confusion of politics, and hand in hand with the devices they have at their fingertips where they can play games all day instead of climbing a f*cking tree and go for a swim in the river and even fall out the tree and break a leg occasionally. It’s all internalized entertainment. There’s this idolization of the superheroes, which really is just a comic strip extension. And from that, it’s very difficult to write a comic-strip story and carry it out successfully on film. That said, I’m not a superhero fan, even though I used to love the comic strips. I think there’s a couple of pretty good Batmans, and that Superman movie by Dick Donner captured the tradition of the comic strip. As we’ve enlarged upon our capabilities visually, I think funnily enough, everything gets less real and less real. And now it seemed to become an excuse for actors to make a lot of money on the side playing superheroes.

DEADLINE: Every been offered one you were tempted to say yes to?

SCOTT: Yeah, been offered, but just said, no, thank you. Not for me. I’ve done two or three superhero films. I think Sigourney Weaver’s a superhero in Aliens. I think Russell Crowe’s a superhero in Gladiator. And Harrison Ford is the super anti-hero in Blade Runner. The difference is, the f*cking stories are better.

DEADLINE: That historical criticism of putting Napoleon in Egypt and gets up close with a corpse in a sarcophagus, why did you do that? Was the corpse a Pharaoh?

SCOTT: He wouldn’t be Tutankhamun, maybe a less important Pharaoh. They did raids and found and brought back a lot of wonderful artifacts from Egypt, including the needles of Cleopatra that are standing now in Paris. There was a lot of plundering done by Napoleon in those foreign places like Italy, where they took all the fine art out of the cathedral in Milan. I saw this wonderful two paintings. One was of a man sitting on a horse staring at the Sphinx, and it was Napoleon. So I thought I had to have that because no one has done the Egyptian campaign, and the truth. They took it over pretty easily. I think the Egyptians threw in the towel immediately. I don’t think there’s even any conflict. And so they were able to, let’s say, enjoy themselves in Egypt at that particular point. While he was there, they were definitely staring at extraordinary artifacts and decided to take them back to France. And then one of the paintings also was in standing there with a group of elegant officers as the casket is being opened to look at the figure that had been wrapped in bandages for probably 3000 years. I thought, I just had to do it, it was such a beautiful counterpoint of two universes. The modern universe of Napoleon Bonaparte, and the ancient universe of the Pharaoh, a lesser Pharaoh, but nevertheless a Pharaoh. He would’ve to be important to being embalmed and actually buried in the casket like that.

So what’s interesting though, as we were doing it, Napoleon, Joaquin, gets this box to stand on, he took off his hat, put it on top of the casket, and stared closely at the Pharaoh. Then he reached out gently to touch the surface of this skin that looks like brown paper at this point. And the Pharaoh suddenly slipped to one side and gave Joaquin a hell of a shock. But I let it run. And he played with that momentarily, got down off the box, and when I said, cut, he said, did you do that? I said, no, it was an accident. It was fantastic. It scared the sh*t out of him. I said, no, no, no, I didn’t do that.

DEADLINE: That New Yorker piece also had Napoleon’s theatrical distributor, Sony Pictures chief Tom Rothman, saying you are reason Joe Biden should rate a second term. You’ve said you don’t want to get political, but how does it feel being cast as a walking, talking advertisement for the U.S. President?

SCOTT: Well, I couldn’t quite work out whether it was an insult or a compliment. I guess what he’s meaning is Joe has got the old shaky walk, but he’s still a walking think tank, man. And if I was Joe, I’d be considering certainly a backup as the vice president because of his age, and that would certainly help things. But I’ve got a lot of admiration for him, my goodness. You’ve got 50 years in the Senate and now the oddest tough circumstances. It’s got to be the worse time to be president of the United States right now, through Covid and two wars. Jesus Christ.

DEADLINE: Still with that New Yorker piece. You trotted out Pauline Kael’s review to show the writer. You got a very flattering profile. Vindication?

SCOTT: Of course. He was a really great journalist, and after all, I’d had that thing framed and hanging behind my desk ever since Blade Runner. It’s a reminder, a warning, just when you think you’ve got it down, you ain’t got sh*t. Just when you think you know everything, you know nothing. So I’ve always thought of that as a nice warning bell. Making Blade Runner in every possible shape and form was tough, the hardest experience I’ve ever had in my life. But because I’m being so experienced in advertising, I gave as good as I got. The guy read it and said, yes, she had this reputation of being pretty tough. I said, tough. She scalped me!. And he said, yeah, okay, okay, okay.

DEADLINE: You were so close to your late brother Tony, who became a great director with a style very different from yours. You were partners. What do you miss most?

SCOTT: Partner? Well, I’ll go deeper and way back. I was at a very good college, which didn’t have a film school. Royal College of Art was excellent, and I eased over to graphic design. This would mean photography and doing. I learned about light meters and printing, and I kind of fancied a career as a fashion photographer, which would be new. I liked that idea of getting into that in the universe because the world is very attractive. And of course you make a lot of money and you meet beautiful women, which is also an attraction.

But my feeling was instead, I need to make a movie. And I was so embarrassed about saying I’d like to be a director. It sounds so ridiculous. I never admitted it. So I kept it secret and I found in a locker at the Royal College of Art, there’s a brand new Bolex, I dunno why it was there, this clockwork camera that runs for a minute in 16 millimeter. I went to the guy’s head of the department and said to him, listen, we’re coming to the holidays. I kind of want to make a movie. And he said, well, you can’t borrow it unless you’ve got a script. I said, alright. So the following midweek, I had written a script and I’d called it Boy and Bicycle, and I storyboard the hell out of it. Went it back to him and he went, well, okay. And he gave me 65 pounds, which is about $80, the camera and a light meter and a tripod and said, you’ve got it for a month. Bring it back undamaged and keep it clean. Read the handbook. Right. So I took it up north to go home on a holiday, and my young brother, Tony Scott, was quite the reverse of what he became. He’d stay in bed until noon, and my mother used to go nuts and say, get out of bed. So I woke him up and said, we’re going to make a movie and you are going to be in it, and you’re going to help me carry the equipment. I’ve got dad’s car. We’re going to go to Harley for, I’m going to shoot this movie. And he went, oh no. I said, yes, get out of bed.

So I pulled him out of bed every day for the next month, and he and I went off together, and while I was puzzling over what to do next and waited for the camera sharpening my pencil, staring at the board in the script, he’d be standing there saying, come on, come on. This is boring! I said, go get me a pack of cigarettes and two sandwiches and a bottle of Coke and f*ck off. So I give him money, he’d go get the food. But he was in the movie and we finished the film. I edited it willy-nilly with great difficulty. And it’s now in the archive of the British Film Institute. But what’s interesting is it really worked in 16 mm. But the interesting was that Tony and I were creating a lifetime together without realizing it.

DEADLINE: How long did it take for that to change him?

SCOTT: Well, I made the cuts. He’s six years younger than me. He’s at this private school, and I said, come and have a look. And he was stunned. We had magic. We had a story. He was the person on screen. He was the voice-over, and there was sound of traffic and music and score, and he was blown away from that moment on. He just followed me right through where my career took me. He went to Leeds, our school, then he went to Royal College. By then, there’s a film school, and Tony made the best two student films I’ve ever seen. So that was it. A career in the making for him, standing in the cold in this grim place between Redcar and Seton, where we’re making the movie. I miss him, and you are right. We were very close.

DEADLINE: You told a story in that magazine piece about facing death climbing the sheer face of a mountain, and him saving you. Every climb a mountain with him again after that one?

SCOTT: You’re f*cking kidding? Absolutely not. No. But he would then move on to the Dolomites and then he would do El Capitan twice. My outlet became tennis and he couldn’t stand it. I thrashed him at tennis and he couldn’t take that. He wouldn’t play tennis. I would never go on the El Capitan. I said to him, you’re f*cking joking. It’s a 4,000-foot vertical face.

DEADLINE: Your most recent films you made in close proximity, House of Gucci and The Last Duel. Two fine ambitious movies released as the business was recovering from the pandemic. Neither was a big hit. Any theories on why, and are you at the point where as long as it makes you happy and reflects your vision, that’s good?

SCOTT: That’s it. That’s the answer. If you’re a painter, you only settle it one way, that morning, and either I love it or don’t love it. And if you don’t love it, you’re going to come back in four months and look again, and go f*ck it, I know what to do now, and you try to change it. That’s moviemaking. And at the end of the day, I learned from the Blade Runner review by Pauline Kael, she taught me a lesson. I thought I’d done something very special. And I had. I know Blade Runner is very special. It’s evergreen. So many big ideas in there that now people feed off it constantly for other movies. I was very happy with it. I’m not a person with a big head, conceited. I’m not like that. I knew it was tricky, but I knew it was special, very special. And she destroyed me, in four pages. You could not ignore it, and so I was down for a while. I was wounded, and then later I framed it to keep it in the office to remind me the only thing that matters is, what did I think of it?

Best of Deadline

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

2023-24 Awards Season Calendar - Dates For Oscars, Emmys, Grammys, Tonys, Guilds & More

'Killers Of The Flower Moon' Set To Receive Palm Springs Film Festival's Vanguard Award

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.