'My Name Is Ted Bundy. I've Never Spoken to Anybody About This.'

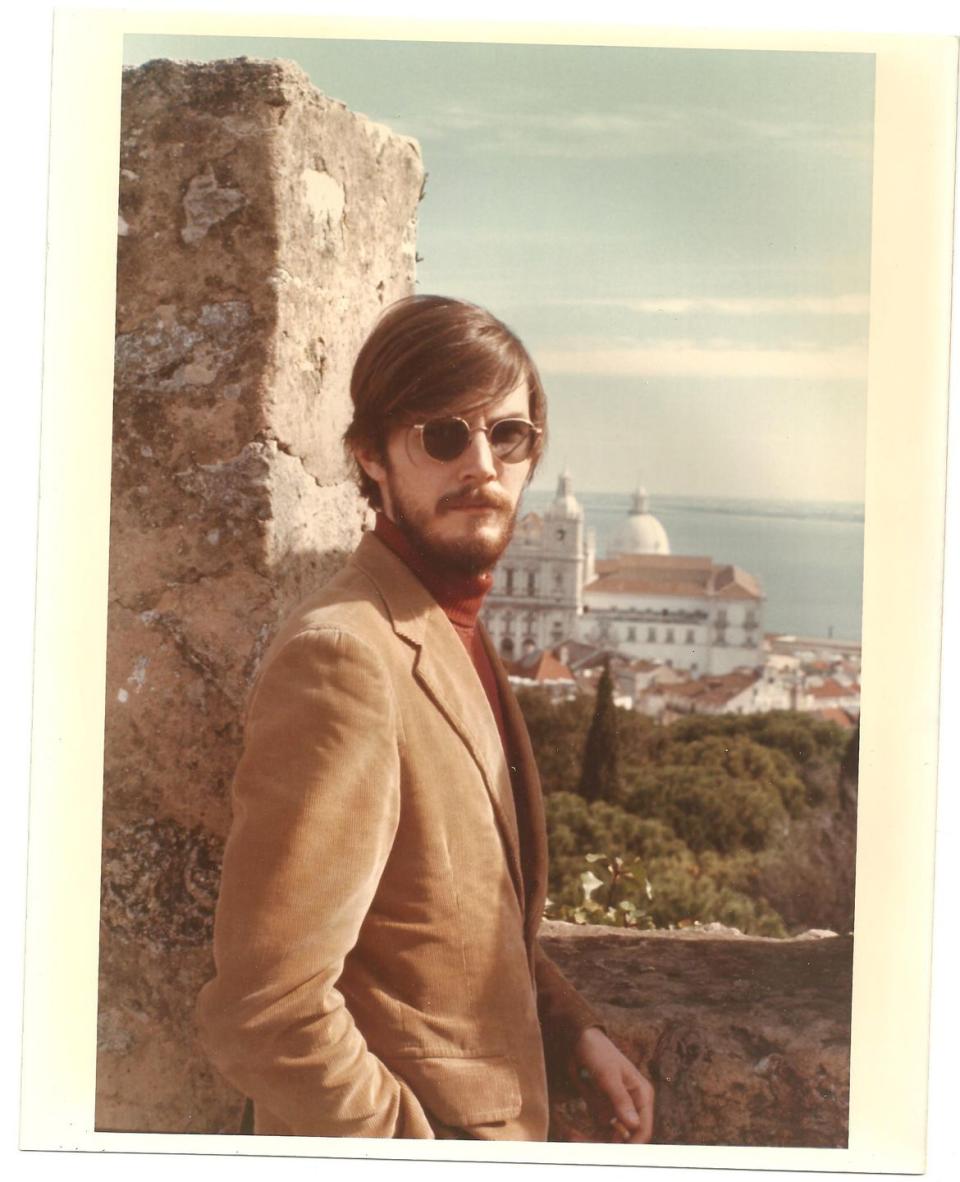

Stephen Michaud was 31 years old when he told Florida State Prison he was an investigator working on Ted Bundy’s appeals case. He was, in fact, a journalist working on a book about the serial killer. Bundy had promised to tell him the real story of what happened, to reveal details that would prove he didn’t brutally murder dozens of women.

“I didn’t really believe it. I didn’t disbelieve it,” Michaud, now 70, says. “But I knew it’d be a hell of a story either way, so I went into the prison with my tape recorder.”

Every couple of weeks, the guards led Michaud down the long, stark corridor past the other prisoners awaiting their executions. They’d make their way to a room in the central part of the prison with one door and windows all the way around. There was a table, two chairs, and an ashtray. When Bundy was brought in, he was wearing a belly chain, handcuffs, and a peach-colored sweatshirt.

For weeks, Bundy waxed on about his childhood, refusing to talk about the murders he was accused of in three states. Michaud was exasperated, and his editors at Simon and Schuster back in New York were getting anxious. So he tried one last tactic: Since Bundy had studied psychology and had gone to a few years of law school, Michaud asked him to speak about the crimes he was accused of in the third person, to act as an expert.

It worked.

“He grabbed my tape recorder, nestled it in his lap, and off he went,” Michaud says. “I was more of a stenographer than a journalist through much of this. I just had to keep the tapes going and take notes.”

Bundy, seemingly speaking about himself, talked about why “a person of this type” might be driven to murder again and again. Michaud and his colleague Hugh Aynesworth had the makings of his 1983 book, The Only Living Witness: The True Story of Serial Sex Killer Ted Bundy. After Bundy was executed, an edited transcript of the tapes was published. Now, portions of those more than 150 hours of audio will be heard for the first time ever in a four-episode Netflix docuseries, Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, premiering January 24.

“In September, I went to New York to help with voiceovers [for the series], and they put me in a room with all four hours of the show,” Michaud says. “I see the pictures and I’m transported back to a time I’d walled off for so many years. After a certain amount of time, Ted became an abstraction to me but, boom, suddenly we’re back in business.

“It was eerie and uncomfortable.”

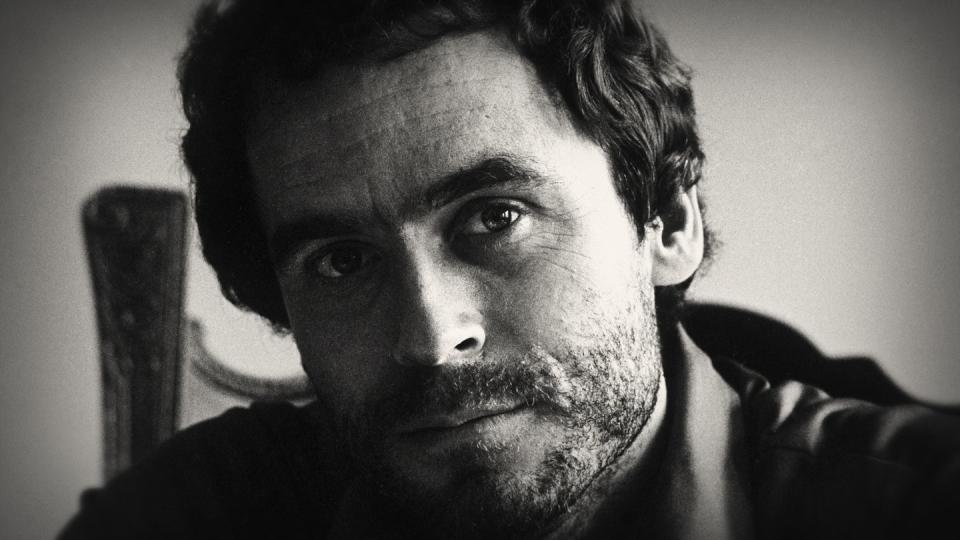

Bundy preyed on young women, beginning his crime spree in Washington in 1974, kidnapping and brutally murdering 22-year-old Lynda Ann Healy. The preppy law student went on to kill in seven states, thanks to two escapes from prison. The documentary shows how disturbingly forgiving people were willing to be because of Bundy’s charm and boyish looks. When he was sentenced to death for the 1978 murder of two women in Florida State University’s Chi Omega sorority house, Judge Edward Cowart said to him: “You’re a bright young man. You’d have made a great lawyer. I would’ve loved to have you practice in front of me. But you went another way, partner. Take care of yourself. I don’t have any animosity towards you. I want you to know that.”

A year later, Bundy received a second death sentence for the murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach.

“Ted stands out because he was quite an enigma: clean-cut, articulate, very intelligent, just a handsome, young, mild-mannered law student,” Michaud says. “He didn’t look like anybody’s notion of someone who would tear apart young girls.”

While on Death Row, Bundy maintained his innocence and began looking for someone to tell his side of the story. Michaud had been working at Business Week and Newsweek before that when he got the call from his agent. He’d worked on crimes stories like the 1975 kidnapping of the Seagram's heir, but it was a long series of coincidences which put him face to face with Bundy. Carole Boone, Bundy’s girlfriend, had befriended a TV journalist in Seattle who was covering the Bundy case. That journalist’s husband’s friend was married to Michaud’s agent. The agent offered the interview to Michaud, who didn’t think twice.

Michaud quit his job and enlisted his former Newsweek colleague Aynesworth to be a partner on the project. Michaud would go to Florida to talk to Bundy while Aynesworth conducted a complete review of all evidence against him. After watching Bundy’s elaborate performances in two Florida courtrooms-“He seemed to be having a hell of a fun time. He was acting as his own attorney, flirting with the girls on the front row, cracking jokes,” Michaud remembers-he arranged a series of calls with Bundy and then finally finangled his way into the prison.

The tapes begin:

It is a little after nine o’clock in the evening. My name is Ted Bundy. I’ve never spoken to anybody about this. I am looking for an opportunity to tell the story as best I can. I’m not an animal and I’m not crazy. I don’t have a split personality. I mean, I’m just a normal individual.

People perceive me differently from how I perceive myself and I need to give others the chance to know what was really going on, what it was really like for me.

Mostly, Bundy tried to control the conversation, framing himself as the star of his own celebrity biography. And he’d talk about his life in prison-portraying himself as much different from his fellow Death Row inmates. “He tried to paint himself as a really stand-up con, and he claimed that nobody messed with him,” Michaud says.

Sometimes, Bundy would show up to their meetings slurring, clearly high. Bundy explained that his girlfriend would sneak drugs in vaginally, and then he’d take him to his cell rectally.

“There are a lot of guys heavy into drugs on Death Row,” Bundy says in the tapes. “I smoked a lot of weed, and I have never in my life been so fucked up. I don’t like the dope that gets you mildy giddy. I mean, when I smoke dope, I like to hallucinate a little bit.” He adds to Michaud:,“I’m gonna bring some drugs down here some time and we’ll smoke it. And Valiums and alcohol.”

Via Michaud, Bundy orchestrated an Orlando courthouse wedding to his girlfriend Boone, to whom he implausibly proposed during one of his murder trials when she was a witness in court. Boone is heard in the documentary describing how the couple was able to consummate the marriage-and how she eventually became pregnant with their daughter, Rose.

“We kept looking out the window,” Boone says in the tapes. “There was a black guard who was real nice. After the first day, they just, they didn’t care. They walked in on us a couple of times.”

Eventually, after Boone found out her new husband was describing to Michaud in the third person horrific details about the crimes he was accused of, she began to distance herself from him. The time spent with Bundy was beginning to weigh on Michaud, as well-the manipulation, the gruesome details of the crimes.

“Ted would sometimes wonder at things he had done and I’d wonder along with him. At one point when I was pushing him about the murder of a specific female he stopped and laughed and said, ‘I think you’d make a great serial killer, too, I really do.’ And he was chortling about that,” Michaud says. “I’d get disoriented. It was a very isolating experience. I often threw up on my way back to my hotel.”

Finally, in late June of 1980, Michaud stepped away, asking his colleague Aynesworth to take over the interviews.

“Last time I talked to Ted I said, we’re going to publish a book. He said, 'I don’t care what you say as long as it sells,'” Michaud says in the documentary. “I was heartily sick of what I was hearing. I was sick of Ted. I walked out of that prison with an enormous sense of relief.”

Nearly, a decade later, in the days before his 1989 execution, in interviews with investigators Bundy finally confessed to the murders of 30 women, in a last-ditch effort to delay his own death.

“When I was interviewing him, he was still fairly fresh off the streets, a year or two. He just was not going to dip in and bring that stuff out for me. And he didn’t,” Michaud says. “His eventual execution was years and years away, he knew that. He had some reason to think he might’ve beaten both cases against him.”

It didn’t work. On January 24, 1989, Bundy was electrocuted in a cellblock at Florida State Prison with about 200 people gathered outside cheering when they heard the news.

The documentary marks 30 years since Bundy’s execution. Michaud was in New York that day, and woke up early to watch it on TV. Since then, Michaud has gone on to write other books, but says he still gets calls about Bundy, including from women who say they were assaulted by the killer and are finally ready to talk.

“Ted leaves an indelible mark on everything he touches,” Michaud says. “You don’t just walk away from it.”

('You Might Also Like',)